Kathleen Jamie at Links of Noltland in Orkney, UK.Credit: Graeme Wilson

Surfacing Kathleen Jamie Penguin Press (2019)

What are nature and culture on a planet we have exhaustively mapped and immeasurably changed? How are we ourselves altered in that process? In Surfacing, the poet and writer Kathleen Jamie explores this liminal space. Through 12 essays, she charts the passage of time in the environment and in us, examining ancient artefacts, dreamscapes and memories as they emerge into the light, and what they tell us about being human in a rapidly shifting world.

Why Nature joined the Covering Climate Now initiative

Surfacing ranges over Jamie’s stints on archaeological digs on a Scottish archipelago and in the High Arctic; a sojourn in China; half-submerged familial memories. Seemingly disparate, the pieces are subtly entangled. There are echoes of Jamie’s previous essay collections, Findings (2005) and Sightlines (2012). These established her unclassifiability as a writer, able to capture with equal depth a peregrine falcon intent on its prey, a Bronze Age burial, the feel of a dissected lymph node.

As in those books, there are no rhapsodies in Surfacing. There is a poet’s economy with words, a stripped clarity.

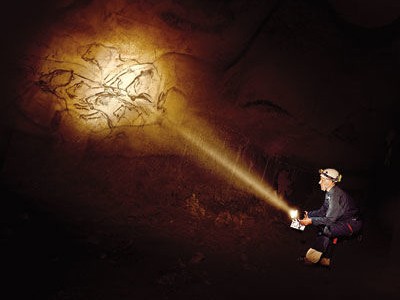

Jamie begins in a cave in the West Highlands of Scotland, contemplating glaciations and climate change. Deep within it in 1995, divers discovered bear bones some 40,000 years old — a find like “reaching the memory of the hill itself”. An aficionado of deep time (she has described her young self as a “teenage antiquarian, thrilled by standing stones”), she trawls museums on the east coast of Britain to view Arctic objects brought back by nineteenth-century whalers. Among narwhal tusks and taxidermied polar bears are beautifully worked Inuit relics, traded for guns.

One such visit leads her to archaeologist Rick Knecht, who runs a dig in a Yup’ik community in the Alaskan region of Beringia. There, fast-melting permafrost is exposing objects crafted from caribou antler, stone, wood and walrus ivory 600 years ago, before missionaries and hunters arrived from the south. ‘In Quinhagak’ records Jamie’s time on the dig. But the essay shape-shifts. It becomes a compelling portrait of a culture recovering its resilience at a climate front line, where iceless winters and burning tundra are the new normal. And where the colonial legacy, not least addiction, is just a few villages away.

Melting permafrost near the town of Quinhagak, Alaska.Credit: Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty

At Quinhagak, “light cascaded down from the whole sky. A ravishing, energising light.” Under it, Jamie mingles with villagers amid long moments looking for bears on the tundra, or shifting mud on the site. In unearthed knife hafts shaped like seals, in villagers’ stories of cranes and walruses, the human and natural coalesce.

Jamie is struck by the Yup’ik habit of attentiveness, and the cohesion it nurtures. She finds her own vision sharpening as she scans the land, and sees herself in some way as scanned by it. In the village, she “noticed that people notice”, surmising that the “whole place must be in constant conversation with itself, holding knowledge collectively”. When elders handle and name the long-buried artefacts — antler-scrapers, root-picks — she feels she is listening to the language of landscape, and to a people coming home.

Half a world away, she reflects on another dig. But this community, on Westray in the Orkney archipelago, moved on five millennia ago. The Neolithic and Bronze Age dwellings at Links of Noltland have been exposed over decades by ferocious winds. Now the site is threatened by erosion — and funding issues. The excavations are something of a sprint.

A big-screen requiem for Ötzi the Iceman

When not scraping through layers of time and materiality, Jamie explores the store of finds — the biggest assemblage of Neolithic objects found in Britain. She is beguiled anew by worked bone and stone, from putative tattooing implements to the ‘Westray Wife’: a tiny sandstone figure with intent eyes, “ancestral and watchful”. But when Jamie imagines which object might be sent into space as an emissary to alien cultures, she opts for a Neolithic stone ploughshare. Ugly and functional, it marks the start of how we’ve tamed and trashed the wild under “the weight of our stuff”.

In the 1980s, Jamie travelled widely in remote regions of Asia: her 1992 book The Golden Peak recounts her time in northern Pakistan. A journey from that era — to Xiahe, a culturally Tibetan town in Chinese territory — unfolds in Surfacing. To reconstruct those weeks at a borderland fraught with uncertainty, Jamie turns domestic archaeologist, burrowing into piles of notebooks and photographs. Through them, she re-enters the “womb-like otherworld” of a temple at Labrang Monastery, meets Chinese students eager to build cultural bridges and joins a gaggle of fellow travellers escaping oppression in Europe. They have arrived, however, only to witness Tibetan culture besieged. The parallel with Yup’ik history is clear.

Surfacing is rich in such mirrorings and mergings. Spirals — carved into the Westray Stone, a magnificent tomb relic — crop up on a ceramic sherd in a newly ploughed field. The motif, she notes, symbolizes how unrelated events can “wheel back into proximity”. And so they do, in the life trajectories of Jamie, her daughter and her father, and in the rise and fall of human settlements. Blazing moments light the way: an eyeful of eagle over a Scottish road, sockeye salmon in an Arctic stream “like silk slashes in a Tudor sleeve”.

At one point, Jamie is midway through a forest somewhere in Scotland, grappling with how to frame the wars and environmental destruction that crowd our collective consciousness. She realizes she is lost. I found myself thinking of Dante Alighieri, coming to himself at life’s midpoint “in a dark wood” as The Divine Comedy opens. But this is a book shrugging off literary allusions. Jamie comes to things openly, listening and looking. And as she shows throughout this astonishing work, it is in looking — attuning ourselves to nature and culture, past and present — that we find our compass.

A big-screen requiem for Ötzi the Iceman

A big-screen requiem for Ötzi the Iceman

Archaeology: A distant mirror

Archaeology: A distant mirror

Q&A: Illuminating the dark

Q&A: Illuminating the dark