Abstract

Background:

The current biomarkers alpha-fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin have limited sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing malignant germ-cell tumours (GCTs). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) from the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters are overexpressed in all malignant GCTs, and some of these miRNAs show elevated serum levels at diagnosis. Here, we developed a robust technical pipeline to quantify these miRNAs in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The pipeline was used in samples from a cohort of exclusively paediatric patients with gonadal and extragonadal malignant GCTs, compared with appropriate tumour and non-tumour control groups.

Methods:

We developed a method for miRNA quantification that enabled sample adequacy assessment and reliable data normalisation. We performed qRT–PCR profiling for miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 cluster miRNAs in a total of 45 serum and CSF samples, obtained from 25 paediatric patients.

Results:

The exogenous non-human spike-in cel–miR–39–3p and the endogenous housekeeper miR–30b–5p were optimal for obtaining robust serum and CSF qRT–PCR quantification. A four-serum miRNA panel (miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p): (i) showed high sensitivity/specificity for diagnosing paediatric extracranial malignant GCT; (ii) allowed early detection of relapse of a testicular mixed malignant GCT; and (iii) distinguished intracranial malignant GCT from intracranial non-GCT tumours at diagnosis, using CSF and serum samples.

Conclusions:

The pipeline we have developed is robust, scalable and transferable. It potentially promises to improve clinical management of paediatric (and adult) malignant GCTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Germ-cell tumours (GCTs) are characterised by clinical and pathological heterogeneity. They occur from the neonatal period through to late adulthood and arise at gonadal or extragonadal sites, including the central nervous system. Malignant GCTs are classified into germinoma and non-germinomatous tumours (yolk sac tumour (YST), embryonal carcinoma (EC) and choriocarcinoma (CHC)), while teratomas (which show extensive somatic differentiation) are generally considered benign (Palmer et al, 2010). The utility of the conventional body fluid protein biomarkers alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) for diagnosis and follow-up is restricted to specific malignant GCT subtypes, as levels are raised predominantly in tumours containing YST and CHC, respectively (Murray and Nicholson, 2011). Moreover, both AFP and HCG can be elevated in non-malignant conditions (Murray et al, 2015a). The initial management of primary gonadal GCTs is complete resection where possible, regardless of serum AFP/HCG levels, thus enabling a histopathological diagnosis. For extragonadal primary sites of disease (e.g., the retroperitoneum and mediastinum), typical radiological findings and raised AFP/HCG markers alone may be sufficient for diagnosis, and indeed for intracranial GCTs, this is the recommended practice in Europe and North America (Nicholson et al, 2002). For ‘marker-negative’ extragonadal cases, however, biopsy is required to establish a formal histopathological diagnosis. Such procedures carry risks of morbidity, due to the difficulties in surgical access to these anatomical sites. Furthermore, disease-monitoring after malignant GCT diagnosis to detect early non-symptomatic relapse currently relies heavily on serial radiological imaging, with associated cumulative radiation exposure and second malignant neoplasm risk (Tarin et al, 2009). Consequently, body fluid biomarkers that offer greater sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing and/or monitoring malignant GCTs would be of major clinical benefit (Murray et al, 2015a).

The ideal biomarker for malignant GCTs would be: stable within body fluids; abundant compared with levels in individuals who were healthy, had benign GCTs or non-GCT pathology; and present regardless of patient age (paediatric or adult), anatomical site of disease (gonadal or extragonadal, including intracranial) or histological subtype (e.g., YST, germinoma and EC) (Murray and Coleman, 2012). Recent years have seen the emergence of microRNAs (miRNAs) as a new generation of biomarkers in malignant GCTs (Murray and Coleman, 2012). MicroRNAs are short, non-protein coding RNAs that are highly stable and well-suited for disease diagnosis and monitoring (Mitchell et al, 2008). We previously demonstrated that the eight main miRNAs from the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters were overexpressed in all malignant GCT tissues (Palmer et al, 2010). By using a multiplexed qRT–PCR protocol, we identified that levels of miRNAs from these two clusters were elevated in the serum of a paediatric patient at the time of diagnosis of an extragonadal malignant GCT, with levels falling and remaining low during uneventful clinical follow-up (Murray et al, 2011b). In the same year, we confirmed these serum findings in extracranial malignant GCTs across a range of representative ages (paediatric and adult), anatomical sites (gonadal and extragonadal) and histological subtypes (YST, germinoma and EC), the majority of which were AFP/HCG marker-negative (Murray et al, 2011a; Murray and Coleman, 2012).

Although our serum miRNA findings in malignant GCTs have since been confirmed and extended, the published studies have exclusively (Belge et al, 2012; Dieckmann et al, 2012; Rijlaarsdam et al, 2015; Spiekermann et al, 2015a; Syring et al, 2015) or predominantly (Gillis et al, 2013) involved adult testicular tumours. In such cases, a consensus panel of four serum miRNAs from the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters (namely miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p) has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific for detecting malignant GCTs (Gillis et al, 2013; Syring et al, 2015). The present study represents the first systematic interrogation of expression of these miRNA clusters in serum/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from patients with paediatric malignant GCTs. Our analysis included serum levels at diagnosis for both ovarian and testicular disease, early detection of relapse and levels in CSF and serum in intracranial disease. Our investigation of the utility of these miRNAs is underpinned by the development of a robust pipeline for their quantification, including essential quality control (QC) steps. The pipeline is scalable, transferable and suitable for widespread adoption into routine clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

The study received approval from the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (reference 02/4/71) and Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee (reference 01/128), and was performed with full informed parental consent. All experimental steps were compliant with the minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments (MIQE; Bustin et al, 2009). Full details are available on request.

Patient demographics and tumours analysed

In total, we analysed 45 body fluid samples (serum n=41, CSF n=4), from a cohort of 25 paediatric patients (0–16 years; Table 1). The cohort comprised a malignant GCT group (n=8; extracranial (n=5) and intracranial (n=3)); a combined group comprising benign GCTs and non-GCT tumours (n=12; extracranial (n=10) and intracranial (n=2)), and a group of control subjects without tumours (n=5). The five extracranial malignant GCTs represented gonadal (three testicular, one ovarian) and extragonadal (sacrococcygeal) disease. The three intracranial malignant GCTs represented two suprasellar site (one germinoma, one non-germinoma) and one pineal site (germinoma). The benign GCTs (n=5) comprised three immature teratomas (ITs) and two mature teratomas (MTs), from both gonadal (n=4) and extragonadal (n=1) sites. The sites of the non-GCT tumours (n=6) were testicular/paratesticular (n=2; one sex cord stromal tumour, one rhabdomyosarcoma), ovarian (n=2; one simple cyst, one small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcaemic type (Bailey et al, 2015)) and intracranial (n=2; one suprasellar WHO grade 1 ganglioglioma and one disseminated MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma). The five samples in the control group were from five age- and gender-matched anonymised subjects, as described previously (Murray et al, 2015b). There were no statistical differences in age between the three patient groups. Full clinicopathological details are given in Table 1.

Overview of pipeline development

The pipeline developed for robust serum miRNA quantification is shown in Figure 1. Components of this pipeline are described in the following sections, with reference to the various colour-coded boxes in Figure 1.

Sample processing and RNA extraction

As part of each patient’s standard clinical care, blood was sampled in serum separator tubes and CSF was collected in plain tubes (Table 1). All specimens were sent to the routine clinical biochemistry diagnostic laboratories at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK, where they were processed and centrifuged within 4 h of receipt. After being used for routine clinical measurements, samples were kept refrigerated at 4 °C for up to 3 days before residual serum/CSF was retrieved and then frozen and stored at −80 °C. At each stage, all samples were processed according to good clinical and laboratory practice, including the use of disposable pipette tips. Only samples without macroscopic evidence of haemolysis were used (Murray et al, 2015b), to avoid substantial technical variation due to the release of intracellular miRNAs from red blood cells (Kirschner et al, 2011; Figure 1, box A).

RNA isolation

RNA from 200 μl of thawed serum or CSF samples was isolated using the miRNeasy serum kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In order to increase RNA yield, we first added MS2 carrier RNA (Roche, Welwyn Garden City, UK) to QIAzol to give a final concentration of 1.25 μg ml−1 (Murray et al, 2015b). To measure the RNA extraction efficiency, we also made a master mix of the exogenous non-human spike-in cel–miR–39–3p from the kit and added a fixed quantity (5.6 × 108 copies) to each sample (Murray et al, 2014), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. This fixed quantity resulted in subsequent cel–miR–39–3p qRT–PCR levels within the expected range for endogenous human serum miRNA levels (Murray et al, 2014). For samples where 200 μl was not available, volumes were made up to 200 μl with an appropriate volume of 1 × PBS. Total RNA was eluted from columns with 100 μl of nuclease-free water and stored at −80 °C.

Initial QC assessment

Samples were screened for suitability for use in subsequent qRT–PCR analyses. Initial QC miRNA assessment was performed for: cel–miR–39–3p (non-human spike-in); miR–30b–5p (housekeeping miRNA); miR–23a–3p and miR–451a (used together for haemolysis assessment (Blondal et al, 2013)). For this initial QC step, miRNA RT and PCRs were performed in singleplex. Five μl of RNA was reverse transcribed using the TaqMan miRNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) using the miRNA-specific stem-loop primer from the relevant TaqMan miRNA assay kit (Life Technologies; Supplementary Table S1), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The final volume of 15 μl for each reaction underwent RT using a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) at 16 °C for 30 min, 42 °C for 30 min, followed by a final step of 85 °C for 5 min, as described previously (Murray et al, 2011b). A singleplex final PCR was then performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. This PCR was performed on a Mastercycler ep_gradient/S realplex (Eppendorf, Stevenage, UK) at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for one minute, as described previously (Murray et al, 2014). To exclude non-specific amplification, a no-template control (NTC) was run for each assay in the QC step. In all cases, no product was detectable (Figure 1, boxes B1–B3).

Consistency of RNA extraction efficiency between samples was satisfactory, as measured by cel–miR–39–3p levels (Cq range 19.4–23.7; s.d. 1.28) (Figure 1, box B2 and Supplementary Figure S1A). Serum levels of the housekeeping miRNA miR–30b–5p (Murray et al, 2014) were also within the expected range (Cq range 23.7–28.8; s.d. 1.40; Figure 1, box B2 and Supplementary Figure S1B). Haemolysis assessment was performed using both miR–451a Cq (Supplementary Figure S1C) and delta Cq (miR–23a–3p minus miR–451a) values (Figure 1, box B3 and Supplementary Figure S1D). This assessment showed that 37 of 41 samples (90.2%) had a delta Cq of <8 and therefore no substantial evidence of haemolysis (Blondal et al, 2013); three samples had a borderline delta Cq value of 8–9 and only a single sample demonstrated haemolysis (delta Cq 10.2; Supplementary Figure S1D). In the absence of further replicate non-haemolysed serum samples, we proceeded to full analysis of these four cases in our evaluation study, but with appropriate caution regarding the results. This approach allowed us to study the potential effects of sample haemolysis on candidate biomarker levels.

MicroRNA quantification

Following initial QC assessment, the next phase of the pipeline was to quantify expression of a larger panel of target and housekeeping miRNAs (Supplementary Table S1). We first performed a multiplexed RT step. The TaqMan miRNA-specific stem-loop RT primers included those for the eight main miRNAs from the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters (Murray et al, 2011b), plus three miRNA housekeeping genes previously shown to be most stable in paediatric serum (namely miR–30b–5p, miR–30c–5p and miR–191–5p (Murray et al, 2014, 2015b), and the non-human spike-in technical control cel–miR–39–3p. To ensure sufficient product for the final PCRs, we performed two identical multiplexed RT reactions for each sample, using 5 μl of RNA eluate in each, and an equal mixture of the relevant RT primers, adapted from (Murray et al, 2011b; Supplementary Table S1). The final volume of 15 μl for each reaction underwent RT, as described above for the initial QC phase (Figure 1, box C).

Multiplexed pre-amplification of RT product

For the pre-amplification step, reactions were multiplexed using the relevant TaqMan assay probes, as described (Murray et al, 2011b). As pre-amplification of specific RT products increases target abundance without introducing bias (Murray et al, 2011b), this allowed greater assay sensitivity and increased the number of target miRNAs measured from the small starting volume. Briefly, an equal mix of all 20 × TaqMan assay probes was prepared for each reaction and diluted to 0.2 × with 1 × Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0), as described previously (Murray et al, 2011b). Two identical pre-amplification reactions (each 50 μl) for each sample contained 25 μl of 2 × pre-amplification master mix (Life Technologies), 25 μl of the diluted TaqMan assay probe mix and 12.5 μl of multiplexed cDNA product (Murray et al, 2011b). After heating to 95 °C for 10 min, 14 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 4 min were run on the GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems; Murray et al, 2011b). The resulting reaction products were diluted 1 : 5 with nuclease-free water, and then the two pre-amplification reaction products for each individual sample were pooled, to make a final volume of 500 μl, sufficient to perform all subsequent singleplex final miRNA PCRs in triplicate (Figure 1, box C).

Final singleplexed PCR of pre-amplification product

Nine μl of the diluted pre-amplified cDNA product was added to 10 μl of TaqMan 2 × Universal PCR master mix, No AmpErase UNG (Applied Biosystems) and 1 μl of each individual 20 × TaqMan assay probe, thereby maintaining ratios identical to those previously described (Murray et al, 2011b). All reactions were performed in triplicate. PCR was performed using the conditions described above for the initial QC phase. For both the QC (Figure 1, boxes B1–B3) and the miRNA quantification steps (Figure 1, box C), the Cq threshold was set manually to 2000 fluorescence units across all PCR plates. NTC samples were also run in the miRNA quantification step; raw mean NTC Cq values are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Test miRNAs with results within two Cq values of the NTC sample or greater were classed as non-expressing (Figure 1, box C).

Data normalisation and analysis

In the miRNA quantification step (Figure 1, box C), cel–miR–39–3p and miR–30b–5p were again measured, to allow assessment of the technical reproducibility of the pipeline. A highly significant correlation was observed between the Cq values obtained in the initial QC (Figure 1, box B) and the miRNA quantification steps (Figure 1, box C), for both cel–miR–39–3p and miR–30b–5p (R2=0.937, P<0.0001 and R2=0.867, P<0.0001, respectively; Supplementary Figure S1E; Figure 1, box D).

When analysing the miRNA quantification data (Figure 1, box C), we first normalised expression of the three endogenous housekeeping miRNAs miR–30b–5p, miR–30c–5p and miR–191–5p (Murray et al, 2014, 2015b) to cel–miR–39–3p, in order to account for any differences in efficiency of the RNA extraction and RT steps. All three housekeeping miRNAs were found to be stably expressed across all 41 serum samples (Figure 2A). Importantly, all the miRNAs used for housekeeping purposes are transcribed from independent chromosomal loci (miR–30b–5p (chromosomal locus 8q24); miR–30c–5p (6q13); miR–191–5p (3p21.31) and miR–23a–3p (19p13.3) (Murray et al, 2015b)). Furthermore, all have previously been shown to be abundant and stably expressed in serum from both paediatric and adult (Blondal et al, 2013) patients. For the four serum samples that showed evidence of haemolysis (grey arrows in Figure 2A), expression levels of these three miRNAs still fell within the normal range, demonstrating their suitability for housekeeping purposes.

Levels of housekeeping miRNAs in the quantification phase of the pipeline ( Figure 1 , box C). (A) Cq values for the housekeeping miRNAs miR–30b–5p, miR–30c–5p and miR–191–5p, obtained after normalisation to cel–miR–39–3p, in all 41 serum samples tested in this study. Sample numbers correspond to those in Table 1. The four samples that had a delta Cq (miR–23a–3p minus miR–451a) value >8 in the QC step (Figure 1, box B3) are indicated by arrows. (B) Correlations between the raw Cq values for the housekeeping miRNAs in (A) above and the raw cel–miR–39–3p Cq values. (C and D) Correlations between the raw (C) and cel–miR–39–3p-normalised (D) Cq values of the three housekeeping miRNAs in all serum samples tested: miR–30b–5p vs miR–191–5p (left), miR–30c–5p vs miR–191–5p (centre) and miR–30b–5p vs miR–30c–5p (right).

By linear regression analysis, levels of cel–miR–39–3p correlated with each of the three endogenous housekeeping miRNAs, miR–30b–5p, miR–30c–5p and miR–191–5p (Figure 2B), although R2 values were only modest, at 0.679, 0.418 and 0.421, respectively. To confirm that cel–miR–39–3p provided additional stringency when using the housekeeping miRNAs for data normalisation, we compared levels of all three with each other, both before (Figure 2C) and after (Figure 2D) cel–miR–39–3p correction. Although the three housekeeping miRNAs showed positive correlations with each other in all comparisons (P<0.0001), addition of cel–miR–39–3p normalisation increased the R2 values in all cases (miR–30b–5p vs miR–30c–5p, R2=0.857–0.925; miR–30b–5p vs miR–191–5p, R2=0.824–0.877; miR–30c–5p vs miR–191–5p, R2=0.888–0.904; Figure 2C and D).

The s.d. of the serum Cq values across the whole cohort of 41 samples was lowest for miR–30b–5p (1.16), when compared with miR–30c–5p (1.52) and miR–191–5p (1.51). Consequently, miR–30b–5p was selected for normalisation of target miRNA quantification data, following normalisation of the miR–30b–5p Cq values to the cel–miR–39–3p levels determined in the miRNA quantification step (Figure 1, box D). Target miRNA levels were quantified relative to miR–30b–5p using the delta Cq method, as described previously (Murray et al, 2014, 2015b). For further details, see Supplementary Materials and Methods. In this evaluation study we applied very stringent criteria for defining miRNA overexpression, whereby only serum miRNA levels that showed a ⩾2.0-fold change in expression (Murray et al, 2014; Murray et al, 2015b) compared with the highest level from the non-tumour control group were considered positive. Differences in serum miRNA levels between experimental groups were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test (P<0.05, significant).

Results

A four-serum miRNA panel (miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p) enables sensitive diagnosis of paediatric extracranial malignant GCTs

In group comparisons, normalised levels of four miRNAs were significantly higher in the serum of paediatric patients with extracranial malignant GCT, compared with both the combined benign GCT/non-GCT tumour group and the non-tumour control group (Figure 3A). This panel comprised the three main miRNAs from the miR–371–373 cluster (miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p and miR–373–3p), plus miR–367–3p from the miR–302/367 cluster. Normalised serum levels of miR–302a–c were not consistently detected above the control threshold in malignant GCT patients (data not shown). As miR–302d–3p levels in all test samples were within two Cq values of the NTC sample, this miRNA was excluded from subsequent analyses.

Relative levels of serum miRNAs in the quantification phase of the pipeline ( Figure 1 , box C) based on samples from patients with extracranial disease. (A) Levels in the three patient groups of: (i) miR–371a–3p, (ii) miR–372–3p, (iii) miR–373–3p and (iv) miR–367–3p by box-and-whisker plot. The broken horizontal line in each graph represents the cutoffs derived from the serum samples, that is, 2.0 times the highest level seen in the non-tumour control group. Box=interquartile range; whiskers=full range of data. (B) Summary heatmap of levels of each member of the four-miRNA panel in serum samples from patients at the time of diagnosis of extracranial disease. Positive results (i.e., miRNA levels ⩾2.0-fold above the highest level observed in the non-tumour control group) are displayed as black boxes. For abbreviations, see Table 1. (C) Individual ROC curves for each member of the four-miRNA panel, namely: (i) miR–371a–3p, (ii) miR–372–3p, (iii) miR–373–3p and (iv) miR–367–3p. Abbreviation: AUC=area under the curve; ROC=receiver operator characteristic.

When assessing cases individually, using our highly stringent criteria for defining miRNA overexpression, positive results were seen in four out of five extracranial malignant GCTs for miR–371a–3p; five of five for miR–372–3p; two of five for miR–373–3p and three of five for miR–367–3p (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S2A–D). There was no obvious association between test miRNA levels, and the presence of haemolysis in this small sample set. The greatest dynamic range in levels was seen for miR–371a–3p, which also showed the clearest separation between positive and negative samples – for example, the lowest level of miR–371a–3p observed in a positive sample (MGCT_ExC#3) was 10-fold higher than the highest non-tumour control (CONT_5; Supplementary Figure S2A). Interestingly, we did not detect miR–371a–3p overexpression in a serum sample reportedly taken at the time of diagnosis of an ovarian YST (MGCT_ExC#4; Supplementary Figure S2A). Further enquiry revealed that the sample had in fact been taken 4 days following complete resection of the ovarian primary tumour, rather than prior to surgery. This is consistent with the described very short half-life for miR–371a–3p in the serum, where the major source has been removed (Dieckmann et al, 2015; Spiekermann et al, 2015a). However, other members of the four-miRNA panel identified remained elevated in this serum sample (Supplementary Figure S2). Together, these observations demonstrated the value of using the whole panel in detecting extracranial malignant GCTs, including where the timing of the ‘diagnostic’ serum sample was suboptimal. In our dataset, miR–372–3p was the only serum miRNA that was elevated in all cases of extracranial malignant GCT.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis, based on varying cutoffs for defining miRNA overexpression, showed that each of the four members of the miRNA panel, miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p, were independently highly sensitive and specific for differentiating paediatric extracranial malignant GCT cases (n=5) from a combined group (n=15) consisting of both the extracranial benign GCT/non-GCT tumour cases and the non-tumour control samples (Figure 3C). We also compared raw Cq (non-normalised) and delta Cq (normalised) values for the four-serum miRNA panel (Supplementary Figure S2E), following recent reports suggesting that relative quantification using normalisation to a housekeeping miRNA may not be required when quantifying serum miRNAs for detection of malignant GCTs (Spiekermann et al, 2015b). We observed a close correlation between raw Cq and delta Cq values for miR–371a–3p (R2=0.969), but for miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p, the correlation values were lower (R2=0.792, 0.824 and 0.773, respectively; Supplementary Figure S2E).

Serum miRNA levels allow early detection of relapse during longitudinal follow-up for extracranial (testicular) malignant GCT

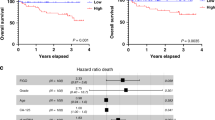

We assessed the value of the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 cluster miRNAs for early detection of relapse in malignant GCT. We examined 18 samples obtained during diagnosis, treatment and follow-up (to day (d) 782) from a patient with a stage 1 testicular mixed malignant GCT (Figure 4). For full clinical details of the case, see Supplementary Results (clinical case 1).

Follow-up of a patient with a testicular mixed malignant GCT (MGCT_ExC#3). (A and B) Show levels of the serum protein biomarkers AFP and HCG, respectively, while (C and D) show levels of miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p, respectively, from d0 (diagnosis) to d160 of follow-up. Asterisks denote the clinical stages of: diagnosis (i), malignant relapse (ii), end-of-treatment (iii) and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND, iv). The arrows show the timing of each chemotherapy cycle. (E) shows representative CT scan images at the four time points described above. The arrows show the retroperitoneal disease.

The primary tumour contained YST, EC, CHC and immature teratoma (IT) components. At the time of diagnosis, the serum levels of miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p and miR–367–3p were elevated (10.1, 2.6- and 2.1-fold, respectively, compared with the highest non-tumour control (Supplementary Figure S2A–D)). Seven of the eight main miRNAs (miR–302d–3p excluded) from the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters were profiled in 17 further longitudinal serum samples. After resection of the primary tumour, levels of miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p decreased to baseline by d14 (Figure 4C and D, respectively). At the time of radiologically detected relapse of malignant disease on d28 (Figure 4E), AFP did not increase, while HCG levels showed only a modest increase of 35.4% from their previous values at d14 (Figure 4A and B, respectively). In striking contrast, miR–371a–3p increased from a relative level of 25.2 on d14, to 100.3 at d28 (398% increase) and 220.7 at d33 (876% increase; Figure 4C). Levels of miR–372–3p also increased at this time, albeit more modestly (Figure 4D).

Once treatment of the malignant relapse commenced (d33), levels of miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p decreased rapidly to baseline (Figure 4C and D), whereas both AFP and HCG showed an initial ‘flare’ (observed at d42; Figure 4A and B), before falling to baseline. Further lymph node enlargement detected radiologically at the end-of-treatment at d101 was not associated with elevations of these miRNAs (nor of AFP/HCG; Figure 4). Following retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (at d140), histopathology showed a diagnosis of growing teratoma syndrome (a non-malignant condition; (Logothetis et al, 1982)), rather than further malignant relapse. In uneventful subsequent clinical follow-up from d140 to d782, AFP/HCG, miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p levels all remained negative (Supplementary Figure S3A). By linear regression analysis of all 18 longitudinal samples, levels of AFP, HCG, miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p each correlated significantly with the other three markers (Supplementary Figure S3B), with the strongest correlation being between miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p levels (R2=0.909; P<0.0001). Outlier points in the serum miRNA and AFP/HCG correlations reflected the more pronounced changes in serum miRNA levels at the time of malignant relapse (at d28; red arrows in Supplementary Figure S3B) and the lack of a serum miRNA flare immediately following administration of chemotherapy (d42; green arrows in Supplementary Figure S3B).

Serum and CSF miRNA levels distinguish intracranial malignant GCTs from intracranial non-GCT pathology in paediatric patients

To determine if the four-miRNA panel comprising miR–371a–3p, miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p could be used to detect intracranial malignant GCT disease, we measured the levels of these miRNAs in four serum and four CSF samples, obtained from a total of five patients (Table 1 and Figure 5). For full clinical details of these cases, see Supplementary Results (clinical cases 2).

Relative levels of serum and CSF miRNAs for diagnosis of primary intracranial GCTs. (A) MR images for three patients with primary intracranial tumours, namely: (i) a suprasellar non-germinomatous GCT (MGCT_IC#2), (ii) a suprasellar germinoma (MGCT_IC#3) and (iii) a ganglioglioma (B-non-GCT_IC#1). (B) Serum levels of: (i) miR–371a–3p and (ii) miR–373–3p, measured in the three patients with primary intracranial disease shown in (A), plus a fourth with a primary intracranial pineal germinoma (MGCT_IC#1). (C) CSF levels of: (i) miR–371a–3p, (ii) miR–372–3p, (iii) miR–373–3p, (iv) miR–367–3p, (v) miR–302a–3p and (vi) miR–302b–3p in the three patients with primary intracranial disease shown in (A). Thresholds (dotted lines) are as in Figure 3. Error bars=s.e.m.

Serum levels of miR–371a–3p and miR–373–3p were positive at diagnosis in the intracranial malignant GCT patients MGCT_IC#3 and MGCT_IC#1, respectively (Figure 5B), both of whom had negative serum and CSF AFP/HCG levels. None of the other miRNAs tested was positive in the other serum samples, using the previously specified serum cutoffs. We extracted RNA from CSF of four patients (MGCT_IC#2, MGCT_IC#3, B-non-GCT_IC#1 and M-non-GCT_IC#1). The M-non-GCT_IC#1 case was a 2-year-old male with MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma (Murray et al, 2015b), who developed intracranial metastatic disease during treatment (Table 1). In each case, a fixed quantity of non-human spike-in cel–miR–39–3p was added, as for the serum samples. We quantified the levels of cel–miR–39–3p, the three housekeeping miRNAs that we had shown to be stable in the serum (miR–30b–5p, miR–30c–5p and miR–191–5p), and miR–124–3p, which had previously been suggested as a suitable CSF housekeeping miRNA (Exiqon, 2013).

Levels of cel–miR–39–3p recovery from the four CSF samples obtained in the miRNA quantification step were equivalent to those observed with the serum sample cohort (mean Cq cel–miR–39–3p CSF 13.27±s.d. 0.12 vs serum 13.98±s.d. 0.26; Supplementary Figure S4A). However, miR–124–3p levels showed a >6 Cq difference across the CSF samples. The greatest miR–124–3p abundance in the CSF was in the MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma sample (M-non-GCT_IC#1; Supplementary Figure S4A), consistent with our previous findings that miR–124–3p is a disease-associated serum biomarker (Murray et al, 2015b). Together, these data indicate that miR–124–3p is not a good candidate for CSF normalisation. In contrast, all three of the other housekeeping miRNAs tested were very stable across the small number of CSF samples examined, albeit with higher mean Cq values than in the serum samples (miR–30b–5p, 17.0 vs 14.9; miR–30c–5p, 19.0 vs 15.7 and miR–191–5p, 16.5 vs 13.6, respectively; Supplementary Figure S4A). Similar to our observations in the serum samples, we identified that the optimal CSF housekeeping miRNA was miR–30b–5p, which had a lower s.d. (0.18) than miR–30c–5p (0.53), miR–191–5p (0.21) and miR–124–3p (3.0; Supplementary Figure S4A).

As with the serum samples, we also quantified CSF levels of miR–23a–3p and miR–451a to assess haemolysis (Supplementary Figure S4B). Despite all four CSF samples being clear and colourless on visual inspection (i.e., showing no evidence of haemolysis), two were above the serum haemolysis threshold (delta Cq >8) using standard methodology (Blondal et al, 2013; Supplementary Figure S4B). For both miR–451a and miR–23a–3p, levels in CSF were lower than in haemolysis-negative serum samples (delta Cq <8, n=37), as indicated by higher mean Cq values (Supplementary Figure S4B). For several samples, the elevations in miR–23a–3p Cq values were substantially greater than those of miR–451a. This indicated that delta Cq (miR–23a–3p – miR–451a) levels were of limited use in indicating haemolysis in CSF.

The levels of miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 were then measured in the three available diagnostic CSF samples from patients with primary intracranial tumours (MGCT_IC#2, MGCT_IC#3 and B-non-GCT_IC#1; Figure 5C). The normalisation and stringent cutoff procedures used for serum samples were applied, with miRNAs that had a ⩾2.0-fold change in expression compared with the highest serum level from the non-tumour control group being considered positive. Using these criteria, CSF miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p levels clearly distinguished the intracranial malignant GCTs from the non-malignant (ganglioglioma) case (Figure 5C). In addition, CSF levels of miR–373–3p, miR–367–3p, miR–302a–3p and miR–302b–3p were also positive in the MGCT_IC#3 germinoma case (Figure 5C). The raw (non-normalised) Cq values for the four miRNAs in the panel identified from serum analysis were similar in the positive and negative CSF samples to those in the positive and negative serum samples, respectively (Supplementary Figure S4C), suggesting there was approximate equivalence in the overall abundance of these miRNAs in serum and CSF.

Discussion

We report a robust, quality controlled pipeline for measuring levels of specific serum and CSF miRNAs in paediatric patients with extracranial and intracranial malignant GCTs. The pipeline benefits from an exogenous non-human spike-in control (cel–miR–39–3p), normalisation using an endogenous housekeeping miRNA (miR–30b–5p) and haemolysis quantification (Blondal et al, 2013). Variation in exogenous cel–miR–39–3p levels between samples may be reported as differences in Cq values (Yamada et al, 2014) or recovery rates (Sanders et al, 2012). The variation we observed in cel–miR–39–3p levels in our cohort, of ∼4 Cq cycles, reflects the genuine difference in RNA recovery between serum samples, which must be normalised to avoid creating false negative/positive results. This variation is consistent with other reports (e.g., Yamada et al, 2014) and less than that described in other studies, which for example, report a recovery rate of 1–56% (i.e., variation of ∼6 Cq values; Sanders et al, 2012).

The correlation data in our relatively small study also indicate an additional benefit of normalising to a stable, endogenously expressed miRNA, that is, miR–30b–5p. This second normalisation step accounts for differences between overall circulating endogenous miRNA levels in individuals, which is not addressed using cel–miR–39–3p levels alone. Our data indicate that this highly stringent pipeline, including two normalisation steps, minimises technical alterations and maximises detection of true biological variation between serum samples. It will be important for prospective studies to evaluate the relative contributions of the two normalisation steps to the avoidance of potential false negative/positive results. In future, once assessed fully, it may be possible to relax the proposed normalisation stringency in circulating miRNA studies.

For CSF analysis, we have shown that miR–30b–5p is stable in a small cohort of samples, demonstrating minimal variation, and may therefore also be suitable for normalisation in future CSF studies. In contrast to previous suggestions (Exiqon, 2013), miR–124–3p does not appear appropriate as a housekeeping gene for CSF normalisation and indeed has been identified as a candidate tumour biomarker in its own right (Murray et al, 2015b).

Haemolysis assessment may also be important during initial QC, as variations in red blood cell lysis between samples may result in altered serum expression levels of miRNAs of interest for technical, rather than biological, reasons (Pritchard et al, 2012). There are a number of methods for such assessment, including the measurement of free haemoglobin (Kirschner et al, 2011), or the established use of delta Cq (miR–23a–3p minus miR–451a) levels (Blondal et al, 2013; Exiqon, 2013; Ludwig et al, 2015; Murray et al, 2015b). The haemolysis results described here, using the latter approach, appear comparable in terms of cutoff thresholds to data obtained utilising different qRT–PCR platforms (Blondal et al, 2013; Ludwig et al, 2015). Haemolysis did not appear to have any major effect on the levels of our candidate biomarkers from the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters, albeit based on a low sample size. However, as it will be critical to avoid false positive results when such tests are established in clinical practice, we recommend that haemolysis assessment should be performed prospectively in circulating miRNA studies, to define precisely what effect haemolysis has on candidate biomarkers in borderline cases. Of note, the miRNA quantification method used to indicate haemolysis in serum samples was not appropriate for CSF, where alternative approaches are required.

From our profiling of all eight main members of the miR–371–373 and miR–302/367 clusters, we derived a panel of four miRNAs that is capable of accurately detecting both extracranial and intracranial malignant GCT disease in paediatric patients (see Supplementary Discussion). Interestingly, the same panel was shown to be of diagnostic value in adults with testicular malignant GCTs (Gillis et al, 2013; Syring et al, 2015). In contrast to recent reports (Dieckmann et al, 2015; Spiekermann et al, 2015a, 2015b), miR–371a–3p alone was not sufficient to identify some malignant GCTs in our patient cohort, including in serum from a patient with an intracranial (pineal) germinoma, where only miR–373–3p was positive. Moreover, the particularly rapid reduction in miR–371a–3p levels following tumour removal in stage 1 disease (Dieckmann et al, 2015; Spiekermann et al, 2015a) will lead to negative results in samples taken more than 1 day post surgery, unlike the other miRNAs in the panel. Our data suggest that expression in body fluids of the four miRNAs in the panel varies across the spectrum of malignant GCT patients and that the full panel provides maximal sensitivity, without affecting specificity. Accordingly, elevated levels of one (or more) member(s) of the panel would represent a positive test result. As miR–367–3p is transcribed from a separate chromosome locus (4q25) to the other three miRNAs from the miR–371–373 cluster (19q13), elevated serum miR–367–3p levels would add confidence to a diagnosis of malignant GCT, as distinct from other malignancies that overexpress miR–371–373 miRNAs but not miR–367–3p. Such tumours include carcinomas of the stomach (Liu et al, 2012) and pancreas (He et al, 2014), as well as primary intracranial tumours with genomic amplification of 19q13 (Pfister et al, 2009; Korshunov et al, 2010).

We have shown, for the first time, that miRNAs from the four-serum miRNA panel can sensitively detect malignant GCT relapse during longitudinal follow-up. In the case studied, miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p detected relapse of an AFP/HCG-secreting (marker-positive) testicular mixed malignant GCT. Indeed, our data suggest that the miRNAs are more sensitive at detecting malignant relapse than conventional protein biomarkers, as they provided a clear positive result at the initial time of radiological relapse (d28), when HCG levels showed only a modest increase and AFP levels had not changed. In addition, miR–371a–3p and miR–372–3p appeared to give a more accurate measure of early response to therapy, as, unlike AFP and HCG, levels did not flare following initiation of chemotherapy. Longitudinal monitoring of further extracranial malignant GCT cases using this panel of serum miRNAs is likely to demonstrate their clinical utility in the follow-up of ‘marker-negative’ cases. In due course, serum miRNA monitoring in malignant GCT patients may reduce the need for serial CT scans, the associated radiation exposure and second cancer risk (Tarin et al, 2009).

It has recently been suggested that, it may not be necessary to perform relative quantification when assessing serum miRNAs as a potential test for testicular malignant GCTs and that raw Cq values provide adequate diagnostic discrimination (Spiekermann et al, 2015b). Our data suggest that overall this is a suboptimal approach when using current methodology. Serum miR–371a–3p has a large dynamic range, allowing a greater degree of separation between positive and negative samples in our study. For this miRNA, the raw Ct (non-normalised) and delta Ct (normalised) values demonstrated a very strong correlation (R2=0.969). However, for the other three miRNAs in the four-serum panel (namely miR–372–3p, miR–373–3p and miR–367–3p), the dynamic range was lower. The difference in mean Cq value between positive and negative samples was ∼4 and the R2 correlation for Cq and delta Cq values were also lower at 0.792, 0.824 and 0.773, respectively. For such miRNAs, differences in RNA extraction efficiency will have a relatively high impact on PCR measurements and will require careful control via relative quantification approaches. Methods that use data normalisation will also enable analysis of low volume samples (<200 μl), for which dilution is required to produce a suitable starting volume. Such a scenario is particularly likely to occur in specimens from paediatric patients and/or certain sample types, such as CSF.

In due course, robust absolute quantification systems may supersede relative quantification when measuring miRNA levels in body fluids (Hindson et al, 2013), although the use of a non-human spike-in or other appropriate ‘standard’ will still need to be employed, to ensure the accuracy of RNA extraction steps and subsequent quantification within and between samples (Sanders et al, 2012). Determining absolute miRNA counts per set volume of serum would allow the determination of universal cutoffs, for example, for miR–451a in assessing haemolysis and for the four-miRNA panel in diagnosing malignant GCT. This should improve sensitivity and specificity overall and provide greater confidence in ‘borderline’ cases, ensuring that diagnostic decisions are not undermined by subtle technical differences. This is important for translation into the clinic, where minimisation of potential false negative/positive results is critical.

In conclusion, we have described a robust pipeline for diagnosis and monitoring of extracranial and intracranial paediatric malignant GCTs. The technical principles and clinical observations described here will underpin the future clinical validation work that is now warranted.

Change history

19 January 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Bailey S, Murray MJ, Witkowski L, Hook E, Hasselblatt M, Crawford R, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz M, Nicholson JC (2015) Biallelic somatic SMARCA4 mutations in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT). Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (4): 728–730.

Belge G, Dieckmann KP, Spiekermann M, Balks T, Bullerdiek J (2012) Serum levels of microRNAs miR-371-3: a novel class of serum biomarkers for testicular germ cell tumors? Eur Urol 61 (5): 1068–1069.

Blondal T, Jensby Nielsen S, Baker A, Andreasen D, Mouritzen P, Wrang Teilum M, Dahlsveen IK (2013) Assessing sample and miRNA profile quality in serum and plasma or other biofluids. Methods 59 (1): S1–S6.

Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT (2009) The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55 (4): 611–622.

Dieckmann KP, Spiekermann M, Balks T, Flor I, Loning T, Bullerdiek J, Belge G (2012) MicroRNAs miR-371-3 in serum as diagnostic tools in the management of testicular germ cell tumours. Br J Cancer 107 (10): 1754–1760.

Dieckmann KP, Spiekermann M, Ruf CG, Oechsle K, Bullerdiek J, Belge G (2015) Is measuring serum levels of microRNA miR-371a-3p superior to the classical biomarkers of testicular germ cell tumors? J Clin Oncol 33 (Suppl 7): abstr 376.

Exiqon (2013) Profiling of microRNA in serum/plasma and other biofluids. Available from http://www.exiqon.com/ls/Documents/Scientific/microRNA-serum-plasma-guidelines.pdf (accessed 4 February 2015).

Gillis AJ, Rijlaarsdam MA, Eini R, Dorssers LC, Biermann K, Murray MJ, Nicholson JC, Coleman N, Dieckmann KP, Belge G, Bullerdiek J, Xu T, Bernard N, Looijenga LH (2013) Targeted serum miRNA (TSmiR) test for diagnosis and follow-up of (testicular) germ cell cancer patients: a proof of principle. Mol Oncol 7: 1083–1092.

He D, Miao H, Xu Y, Xiong L, Wang Y, Xiang H, Zhang H, Zhang Z (2014) MiR-371-5p facilitates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and decreases patient survival. PLoS One 9 (11): e112930.

Hindson CM, Chevillet JR, Briggs HA, Gallichotte EN, Ruf IK, Hindson BJ, Vessella RL, Tewari M (2013) Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nat Methods 10 (10): 1003–1005.

Kirschner MB, Kao SC, Edelman JJ, Armstrong NJ, Vallely MP, van Zandwijk N, Reid G (2011) Haemolysis during sample preparation alters microRNA content of plasma. PLoS One 6 (9): e24145.

Korshunov A, Remke M, Gessi M, Ryzhova M, Hielscher T, Witt H, Tobias V, Buccoliero AM, Sardi I, Gardiman MP, Bonnin J, Scheithauer B, Kulozik AE, Witt O, Mork S, von Deimling A, Wiestler OD, Giangaspero F, Rosenblum M, Pietsch T, Lichter P, Pfister SM (2010) Focal genomic amplification at 19q13.42 comprises a powerful diagnostic marker for embryonal tumors with ependymoblastic rosettes. Acta Neuropathol 120 (2): 253–260.

Liu H, Zhu L, Liu B, Yang L, Meng X, Zhang W, Ma Y, Xiao H (2012) Genome-wide microRNA profiles identify miR-378 as a serum biomarker for early detection of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett 316 (2): 196–203.

Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Trindade A, Johnson DE (1982) The growing teratoma syndrome. Cancer 50 (8): 1629–1635.

Ludwig N, Nourkami-Tutdibi N, Backes C, Lenhof HP, Graf N, Keller A, Meese E (2015) Circulating serum miRNAs as potential biomarkers for nephroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (8): 1360–1367.

Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O’Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M (2008) Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105 (30): 10513–10518.

Murray MJ, Bailey S, Raby KL, Saini HK, de Kock L, Burke GA, Foulkes WD, Enright AJ, Coleman N, Tischkowitz M (2014) Serum levels of mature microRNAs in DICER1-mutated pleuropulmonary blastoma. Oncogenesis 3: e87.

Murray MJ, Coleman N (2012) Testicular cancer: a new generation of biomarkers for malignant germ cell tumours. Nat Rev Urol 9 (6): 298–300.

Murray MJ, Halsall D, Nicholson JC, Coleman NC (2011a) Identification of microRNAs from the miR-371∼373 and miR-302 clusters as potential serum biomarkers of malignant germ cell tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57: 743.

Murray MJ, Halsall DJ, Hook CE, Williams DM, Nicholson JC, Coleman N (2011b) Identification of microRNAs from the miR-371∼373 and miR-302 clusters as potential serum biomarkers of malignant germ cell tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 135 (1): 119–125.

Murray MJ, Nicholson JC (2011) Alpha-fetoprotein. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 96 (4): 141–147.

Murray MJ, Nicholson JC, Coleman N (2015a) Biology of childhood germ cell tumours, focussing on the significance of microRNAs. Andrology 3 (1): 129–139.

Murray MJ, Raby KL, Saini HK, Bailey S, Wool SV, Tunnacliffe JM, Enright AJ, Nicholson JC, Coleman N (2015b) Solid tumors of childhood display specific serum microRNA profiles. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24 (2): 350–360.

Nicholson JC, Punt J, Hale J, Saran F, Calaminus G (2002) Neurosurgical management of paediatric germ cell tumours of the central nervous system—a multi-disciplinary team approach for the new millennium. Br J Neurosurg 16 (2): 93–95.

Palmer RD, Murray MJ, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Abreu-Goodger C, Muralidhar B, Pett MR, Thornton CM, Nicholson JC, Enright AJ, Coleman N (2010) Malignant germ cell tumors display common microRNA profiles resulting in global changes in expression of messenger RNA targets. Cancer Res 70 (7): 2911–2923.

Pfister S, Remke M, Castoldi M, Bai AH, Muckenthaler MU, Kulozik A, von Deimling A, Pscherer A, Lichter P, Korshunov A (2009) Novel genomic amplification targeting the microRNA cluster at 19q13.42 in a pediatric embryonal tumor with abundant neuropil and true rosettes. Acta Neuropathol 117 (4): 457–464.

Pritchard CC, Kroh E, Wood B, Arroyo JD, Dougherty KJ, Miyaji MM, Tait JF, Tewari M (2012) Blood cell origin of circulating microRNAs: a cautionary note for cancer biomarker studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 5 (3): 492–497.

Rijlaarsdam MA, van Agthoven T, Gillis AJ, Patel S, Hayashibara K, Lee KY, Looijenga LH (2015) Identification of known and novel germ cell cancer-specific (embryonic) miRs in serum by high-throughput profiling. Andrology 3 (1): 85–91.

Sanders I, Holdenrieder S, Walgenbach-Brunagel G, von Ruecker A, Kristiansen G, Muller SC, Ellinger J (2012) Evaluation of reference genes for the analysis of serum miRNA in patients with prostate cancer, bladder cancer and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol 19 (11): 1017–1025.

Spiekermann M, Belge G, Winter N, Ikogho R, Balks T, Bullerdiek J, Dieckmann KP (2015a) MicroRNA miR-371a-3p in serum of patients with germ cell tumours: evaluations for establishing a serum biomarker. Andrology 3 (1): 78–84.

Spiekermann M, Dieckmann KP, Balks T, Bullerdiek J, Belge G (2015b) Is relative quantification dispensable for the measurement of microRNAs as serum biomarkers in germ cell tumors? Anticancer Res 35 (1): 117–121.

Syring I, Bartels J, Holdenrieder S, Kristiansen G, Muller SC, Ellinger J (2015) Circulating serum miRNA (miR-367-3p, miR-371a-3p, miR-372-3p and miR-373-3p) as biomarkers in patients with testicular germ cell cancer. J Urol 193 (1): 331–337.

Tarin TV, Sonn G, Shinghal R (2009) Estimating the risk of cancer associated with imaging related radiation during surveillance for stage I testicular cancer using computerized tomography. J Urol 181 (2): 627–632, discussion 632–633.

Yamada A, Cox MA, Gaffney KA, Moreland A, Boland CR, Goel A (2014) Technical factors involved in the measurement of circulating microRNA biomarkers for the detection of colorectal neoplasia. PLoS One 9 (11): e112481.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for study participation. We are grateful to Mrs Sophie Wool and Mrs Jane Tunnacliffe, Senior Research Nurses, Department of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge for patient recruitment. We also thank Dr David Halsall, Ms Amy Munro and Mr Jonathan Broomfield (Department of Biochemistry, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK) for assistance with sample handling and storage, and Professor Richard Samworth (University of Cambridge) for statistical advice. Grant funding was from CwCUK/GOSHCC (to MJM, KLR, JCN and NC), SPARKS (to MJM, JCN and NC), AstraZeneca (to EB, HB and BD), CRUK (to NC), MRC (to MJM) and an Erasmus MC MRACE grant (to MAR). The authors also thank the Max Williamson Fund and The Perse Preparatory School, Cambridge for supporting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Murray, M., Bell, E., Raby, K. et al. A pipeline to quantify serum and cerebrospinal fluid microRNAs for diagnosis and detection of relapse in paediatric malignant germ-cell tumours. Br J Cancer 114, 151–162 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.429

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.429

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Refining the serum miR-371a-3p test for viable germ cell tumor detection

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

MicroRNA-profiling of miR-371~373- and miR-302/367-clusters in serum and cerebrospinal fluid identify patients with intracranial germ cell tumors

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Biomarkers of disease recurrence in stage I testicular germ cell tumours

Nature Reviews Urology (2022)

-

Detection of recurrences using serum miR-371a-3p during active surveillance in men with stage I testicular germ cell tumours

British Journal of Cancer (2022)

-

Associations of serum levels of microRNA-371a-3p (M371) with risk factors for progression in nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumours clinical stage 1

World Journal of Urology (2022)