Abstract

Background:

Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a fatal disease with 5-year survival rates of <5% in Northern Iran. Oesophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD) is the precursor histologic lesion of ESCC. This pilot study was conducted to assess the feasibility, safety, and acceptability of non-endoscopic cytological examination of the oesophagus and to provide initial data on the accuracy of cytological atypia for identifying patients with ESD in this very-high-risk area.

Methods:

Randomly selected asymptomatic participants of the Golestan Cohort Study were recruited. A cytological specimen was taken using a capsule sponge device and evaluated for atypical cells. Sections of the cytological specimen were also stained for p53 protein. Patient acceptability was assessed using a visual analogue scale. The cytological diagnosis was compared with a chromoendoscopic examination using Lugol’s solution.

Results:

Three hundred and forty-four subjects (43% male, mean (s.d.) age 55.6 (7.9) years) were referred to the study clinic. Three hundred and twelve met eligibility criteria and consented, of which 301 subjects (96.5%) completed both cytological and endoscopic examinations. There were no complications. Most of the participants (279; 92.7%) were satisfied with the examination. The sensitivity and specificity of the cytological examination for identifying subjects with high-grade ESD were 100 and 97%, respectively. We found an accuracy of 100% (95% CI=99–100%) for a combination of cytological examination and p53 staining to detect high-grade ESD.

Conclusions:

The capsule sponge methodology seems to be a feasible, safe, and acceptable method for diagnosing precancerous lesions of the oesophagus in this population, with promising initial accuracy data for the detection of high-grade ESD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Oesophageal cancer (EC) is the eighth most common cancer (456 000 new cases per year) and the sixth most frequent cause of cancer death (400 000 deaths per year) worldwide. Around 80% of ECs occur in developing countries (Ferlay et al, 2013).

Very high rates of EC have been reported from the Central Asian Esophageal Cancer Belt, an area that extends from the Caspian Sea to Northern China. Golestan Province, Iran, located at the western end of this belt, has been documented as a high-risk area for EC since the 1960s (Mahboubi et al, 1973). Despite declining trends since these early reports, EC remains a frequent malignancy in both men and women in Northern Iran (Semnani et al, 2006; Roshandel et al, 2012a). Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the most important histological type of EC in Northeastern Iran, comprising more than 90% of EC cases (Kamangar et al, 2007; Islami et al, 2009b), and it is a major health problem in this area.

ESCC develops by progression from dysplastic lesions within the squamous epithelium of the oesophagus (Das, 2010). In other words, oesophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD) is the histological precursor lesion for ESCC (Dawsey et al, 1994b; Wang et al, 2005). Several risk factors have been proposed for the development of ESD and ESCC, including genetic susceptibility (Akbari et al, 2007, 2011), poor oral health (Abnet et al, 2008), exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Abedi-Ardekani et al, 2010), drinking hot tea (Islami et al, 2009c), and low socioeconomic status (Islami et al, 2009a). Some of these risk factors are modifiable and preventable, but others are not, suggesting that primary prevention may be only partially successful. An alternative method for controlling this fatal disease is to detect and eliminate ESD and hence to prevent the possibility for its progression into ESCC. This is the main goal of EC-screening programmes (Yang et al, 2012).

Endoscopy with Lugol’s iodine staining and biopsy is the most accurate method for diagnosing ESD (Dawsey et al, 1998; Das, 2010). However, it is an invasive and expensive procedure, which may not be acceptable to the asymptomatic population in high-risk areas, including Golestan Province (Roshandel et al, 2014), suggesting the need for other non-endoscopic screening methods. Different methods have been considered for developing non-endoscopic screening programmes for ESCC, including risk stratification by patient risk factors, cytological examination of oesophageal cell samples, evaluation of molecular biomarkers (for example, p53), and genetic profiling (Roshandel et al, 2012b). Kadri et al (2010) demonstrated that a non-endoscopic capsule sponge device (Cytosponge) coupled with a biomarker (trefoil factor 3) was an acceptable and valid method for early detection of Barrett’s oesophagus, the precancerous lesion of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. The present study was conducted in an asymptomatic population from Golestan Province of Iran, to assess the feasibility, safety, and acceptability, and to provide an initial indication of accuracy for a capsule sponge examination coupled with cytological examination and p53 staining as a non-endoscopic screening method for the detection of ESD.

Materials and Methods

This was a pilot study conducted on a randomly selected sample of asymptomatic participants of the Golestan Cohort Study (GCS; Pourshams et al, 2010). The GCS includes 50 045 middle-aged individuals who were enroled in the eastern half of Golestan Province, Iran, between January 2004 and June 2008. The main aim of this ongoing cohort study is to determine the risk factors of upper GI cancers, especially EC.

Patient selection and procedures

From all 50 045 GCS participants, those living in remote areas and had difficulty coming to the study site (n=19 919), and subjects who were dead or had cancer at the time of recall (n=1975) were excluded. The remaining GCS participants (n=28 151) were stratified by age, sex, and ethnicity, and using a stratified random sampling, 2000 subjects were selected. Selected subjects were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the study. Subjects who accepted were asked to perform an overnight fast and then come to the Atrak Clinic, a referral clinic for upper gastrointestinal diseases in eastern Golestan Province. A consort diagram is shown in Figure 1.

At Atrak clinic, detailed information about the project, including the procedures, risks, and benefits, were provided to eligible subjects and informed consent was obtained. Subjects with dysphagia, oesophageal varices, coagulopathies, severe pulmonary disease, cirrhosis of the liver, hypersensitivity to iodine solution, myocardial infarction, or stroke in the past 6 months or a history of malignant disorders were excluded. Participants were then asked to fill in a brief questionnaire including data on current age and gender before the capsule sponge examination.

To obtain a cytological sample, we used a commercially available capsule sponge device permitted for use in Iran (Oesotest, Actimed SA, St-Sulpice, Switzerland; Supplementary Figure S1). Each subject was asked to place the capsule and bunched up string in their mouth, leaving about 10 cm of string outside. The capsule was then swallowed with about 150 ml of water, holding the end of the string to avoid swallowing it along with the capsule. The subject was then asked to wait for 5 min to allow the gelatin capsule to dissolve so that the sponge inside the capsule was released. The sponge was then slowly withdrawn up the oesophagus by pulling the string. The retrieved and expanded sponge containing the cytological specimen was placed in a preservative fluid (Surepath, BD Diagnostics, Durham, NC, USA) and transferred to the cytology lab.

Structured forms were used to record and report adverse events. The subjects’ experience of the capsule sponge examination was assessed using a visual analogue scale from 1 to 6 shortly after the procedure and before endoscopy. On this scale, a score of 1 and 6 represented the best and worst satisfaction levels, respectively, and a cartoon face was used to assist interpretation of this scale, which was found to be necessary in this rural population (Figure 2). A score between 1 and 4 was categorised as acceptable for the purposes of analysis.

After the capsule sponge examination, subjects were referred to the endoscopy room where they underwent an endoscopy within 2 h. Before performing endoscopic examination, a local anaesthetic drug (xylocaine) was sprayed into the back of the throat to make it numb. Then subjects were sedated using 2–5 mg intravenous midazolam injection. A standard endoscopic examination of the oesophagus was performed, and 20 cc of 1.4% Lugol’s iodine was sprayed on the oesophageal mucosa to identify abnormal lesions. During endoscopic examination, normal oesophageal mucosa turned brown (iodine positive) and dysplastic lesions remained unstained (iodine negative), called unstained lesions (USLs). One biopsy was taken from each USL as well as from normally stained mid-oesophageal mucosa and was sent to pathology lab.

Subjects with clinically important histological lesions, including moderate and severe dysplasia (high-grade dysplasia), were referred for further evaluation and treated by one or more of the available standard therapeutic options including endoscopic mucosal resection, surgery, or chemotherapy after proper staging of disease.

Sample preparation and analysis

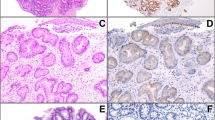

Capsule sponge specimens were processed to allow the cells to form a clot, using a method previously described by us (Lao-Sirieix et al, 2009). The clots were then processed into paraffin blocks, and regular and positively charged slides were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The results were reviewed by independent expert cytopathologists (MO’D and SM) who followed the Bethesda system (Solomon et al, 2002) to make cytological diagnoses using the following categories: normal, atypical squamous cells (ASC), and ASC of uncertain significance (ASCUS). ASCUS was defined as cellular abnormalities that were more marked than those attributable to reactive changes but that quantitatively or qualitatively fell short of a definitive diagnosis of squamous intraepithelial lesion. ASC was used for specimens containing cells with cytologic features of squamous intraepithelial lesions. Due to the high prevalence of p53 mutation in this disease (Petitjean et al, 2007; Agrawal et al, 2012), p53 immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed using a mouse anti-p53 antibody (DO7; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK) using a fully automated IHC instrument, the Leica Bond-Max (Leica Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary antibody was omitted in negative control slides. Sections of the oral carcinoma 3 cell line were used to prepare positive control slides. The p53-stained sides were reviewed by a trained researcher (GR) and an expert cytopathologist (SM). All fields of the slides were assessed. The results were scored, considering the intensity of the nuclear stain in squamous cells. The intensity of nuclear stain in positive control slides was considered as strong. Then, other slides were compared with the positive control slides for the intensity of nuclear stain. Slides with one or more squamous cells with nuclear staining intensity similar to that of positive controls were considered as P53-positive slides. Otherwise, they were scored as negative.

Endoscopic biopsy samples were processed into paraffin blocks, and H&E-stained slides were prepared, which were reviewed by independent expert histopathologists (MS and AN). A histological diagnosis was made using previously described criteria (Dawsey et al, 1994a) and the Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia (Schlemper et al, 2000).

Statistical analysis

Considering the pathological diagnosis as the gold standard, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of the cytological diagnoses and P53 staining for identifying patients with histologic ESD were calculated. Because of the clinical importance of high-grade (moderate or severe) ESD (Wang et al, 2005; Taylor et al, 2013), these statistics were also calculated for identification of patients with a histologic diagnosis of high-grade ESD.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committees of the Digestive Disease Research Institute (DDRI) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) and Golestan University of Medical Sciences (GOUMS).

Results

A total of 2000 randomly selected GCS participants were telephoned (Figure 1). One thousand nine hundred and six subjects (95.3%) were successfully called and invited to participate in the study. Of these, 344 subjects (18.0%) accepted to take part and came to Atrak Clinic and the remaining refused to participate. The reason for almost all of these refusals was the subjects’ concern about the endoscopic examination, and none of the subjects expressed any concern about the new capsule sponge method. Twenty-six subjects who came to Atrak Clinic (7.5%) could not be consented and declined to take part, again because of concern about the endoscopic examination.

Three hundred and twelve eligible subjects were referred for a capsule sponge examination. Only one subject could not complete the examination because of retching. Hence, the capsule sponge examination was successfully completed in the remaining 311 subjects (99.7%). No other adverse events were reported. The capsule sponge examination was acceptable (score 1–4) to 92.7% of our subjects. Figure 2 shows the levels of satisfaction among the screened subjects. All of cytological slides were successfully reviewed by cytopathologists and the specimen was sufficient to permit a diagnosis to be made in all cases.

The endoscopic examination was completed in 301 subjects. Eight subjects experienced adverse events that were not clinically significant (one episode of agitation after Lugol’s staining, one patient experienced chest pain, four had vomiting, and two complained of cutaneous rashes), and all of them were resolved without any intervention.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of subjects included and excluded from the study during the study process. Three hundred and one subjects completed both cytological and endoscopic examinations and were included in the final analysis. Forty-two percent of these subjects were male, and their mean (s.d.) age was 54.9 (7.6) years. Table 2 shows the numbers and proportions of these participants with ASC and ASCUS in their capsule sponge samples, by age and gender. Thirteen subjects (4.3%) were positive for ASC, 22 subjects (7.3%) were diagnosed as ASCUS, and 266 (88.4%) were diagnosed as normal. The proportions of ASC were higher in women and in older subjects. The cell samples from 36 (12.0%) of the 301 subjects stained positively for p53. Table 3 categorises the subjects by the worst histologic diagnosis of their endoscopic biopsies and shows the correlation between the cytologic diagnoses and p53 staining of the capsule sponge specimens and the subjects’ worst histologic diagnoses.

In total, 131 USLs (appeared as discrete lesions) were found on endoscopic examinations (Supplementary Figure S2). The most common abnormal histologic diagnoses were oesophagitis (88 subjects; 29.2%) and ESD (18 subjects; 6.0%). The diagnoses of ‘atypical change indefinite for dysplasia’ and ‘basal cell hyperplasia’ were made in 9 (3.0%) and 5 (1.7%) subjects, respectively, and 181 (60.1%) were diagnosed as normal. ASC was found in five (35.7%) of the cases with mild ESD and four (100%) of the subjects with moderate or severe (high-grade) ESD. The cytological slides from all four subjects with high-grade ESD and none of those with mild ESD were positive for p53. Table 4 shows the screening characteristics of the cytological findings of ASC, ASC or ASCUS, p53 positivity, and ASC and p53 positivity for identifying patients with a histologic diagnosis of ESD or high-grade ESD. Our preliminary results show high sensitivities and specificities for the capsule sponge examination to detect patients with high-grade ESD.

Discussion

ESCC is a fatal disease and a major health problem in high-risk areas. The absence of a true serosal layer in the oesophageal wall leads to rapid invasion into neighbouring structures (Ludeman and Shepherd, 2005), resulting in a poor prognosis in most cases (Aghcheli et al, 2011). We hypothesised that earlier diagnosis of a tumour or its precursor lesion (ESD) by screening of asymptomatic high-risk individuals may reduce mortality and the individual and societal burden of this fatal cancer (Lao-Sirieix and Fitzgerald, 2012). Endoscopic examination is currently the gold standard method for diagnosis of ESD, but it is too invasive and expensive to be considered for population screening, especially in low- or middle-income countries. The aims of this study were to assess the feasibility, safety, and accuracy of a non-endoscopic method (capsule sponge examination) for screening of ESD in a high-risk area in Northeastern Iran.

Capsule sponge examination was considered an acceptable test by almost all (92.7%) of the eligible subjects in this study. The reason for almost all of the refusals on the telephone or in the clinic among those invited to participate in the study was the subjects’ concern about the endoscopic examination, and none of the refusals were related to the capsule sponge examination. Cytological examination was successfully completed in all but one of the participants, and no significant adverse events were reported. These findings suggest that the capsule sponge examination is feasible, safe, and acceptable in our population.

Cytological examination has been used for early diagnosis of ESCC since the 1970s (Nabeya et al, 1979). Different methods have been used for taking cytological specimens from the oesophagus, including brush cytology (Dowlatshahi et al, 1978; Lazarus et al, 1992) and balloon and sponge samplers (Roth et al, 1997; Pan et al, 2008). All of these methods were acceptable to their study populations and were successfully completed in most of the study subjects, without any significant adverse events. But none of these studies resulted in the development of a screening programme at a population level. Recently, newer capsule sponge devices coupled with different sample processing methods have shown promise for the detection of Barrett’s oesophagus (Kadri et al, 2010; Lao-Sirieix and Fitzgerald, 2012). Therefore, cytological examination of the oesophagus using the new devices and methods may be considered for ESCC screening at a population level in high-risk areas, including Northern Iran.

Although the current study is underpowered for a robust estimate of accuracy, our results are very encouraging, with a high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (97%) for cytological examination to detect high-grade ESD. These screening characteristics were even slightly improved by addition of IHC staining for p53. We found an accuracy of 100% (95% CI=99–100%) for a combination of a cytological diagnosis of ASC and p53 staining to detect high-grade ESD. Coupling p53 staining to routine cytological assessment may also make the results of such screening less subjective, which potentially may save time and human resources.

We found higher acceptance rates in female subjects. In our study population, most of the females were housewives and had more free time to come to study site compared with men. This may explain such difference in acceptance rate between men and women in this study. Our results also showed higher rates of refusals in older individuals. The most possible explanation for this finding is the presence of comorbidities in older subjects and their concerns about complications of endoscopic examination.

We found low prevalence of ESD. Previous reports from our region (Semnani et al, 2006; Roshandel et al, 2012a) showed a decreasing trend in the incidence of EC during recent decades, suggesting a decrease in the prevalence of EC risk factors in Golestan province. This may explain the low prevalence of dysplasia in our study, because the risk factors of dysplasia are similar to those of EC (Wei et al, 2005).

In this study, we considered high-grade ESD as the outcome of interest in our screening programme, because it is the clinically most important precursor lesion of ESCC and the point in the spectrum of ESD at which therapeutic intervention would be recommended. The results of a previous study from China reported that the relative risk for development of ESCC is considerably higher in subjects with high-grade ESD than in those with low-grade ESD (Dawsey et al, 1994b; Wang et al, 2005; Taylor et al, 2013), suggesting that subjects with high-grade ESD need to be treated as soon as possible, but those with low-grade ESD can be followed by repeated examinations, without urgent treatment (Wang et al, 2005; Taylor et al, 2013). Furthermore, one of the major recent advantages of ESCC-screening programme is that curative endoscopic treatments are now available using a combination of endoscopic resection and radiofrequency ablation, with promising results (Pech et al, 2007; Bergman et al, 2011).

Compared with previous similar studies (Roth et al, 1997; Pan et al, 2008), we found a considerably higher sensitivity for detecting high-grade ESD. Differences in sampling devices or sample processing methods may explain the better results in our study. A diagnosis could be made in all of the cytological slides in our study, suggesting that cytological specimens from all of our participants were satisfactory for evaluation of squamous cells. In contrast, the results of previous studies (Roth et al, 1997; Pan et al, 2008) showed that the cytological specimens were unsatisfactory for evaluation of squamous cells in 1 and 14% of samples taken by balloon and sponge samplers, respectively. It should also be noted, however, that our high-grade ESD results are based on only four subjects with this outcome, which is reflected by the wide confidence intervals around our sensitivity estimates. This was a significant limitation of our study. Thus, additional capsule sponge studies are needed, which include larger numbers of subjects with high-grade ESD, to evaluate the reproducibility and stability of our current findings. This may be achieved by selecting especially high-risk individuals for screening, using previously identified risk factors (Roshandel et al, 2014) and risk stratification models (Etemadi et al, 2012).

The proportion of subjects in our study with ASC was considerably higher in subjects older than 60 years. Age is a known risk factor for development of ESD and ESCC. Therefore, the lower age limit for screening may be an important consideration when designing future studies’ ESCC-screening programmes at a population level.

Our findings showed that including ASCUS (in addition to ASC) as a positive result decreased the specificity of the capsule sponge examination for detecting high-grade ESD from 97 to 90% (Table 4). In other words, this broader definition of cytology positivity would result in a higher rate of false positive cases, which would decrease the efficiency and increase the costs of a screening programme. Therefore, our preliminary results would suggest that ASCUS cases should be classified as negative, and only subjects with ASC should be referred for an endoscopic examination to confirm the diagnosis of high-grade ESD.

Considering both our findings and those reported from a recent similar study from the United Kingdom (Kadri et al, 2010), it may be advisable to use capsule sponge examinations for screening of both ESCC and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. This is especially relevant in view of the increasing trends in the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in Golestan Province, Iran (Ghasemi-Kebria et al, 2013).

In conclusion, a capsule sponge examination coupled with a cytological examination and p53 IHC was a feasible, safe, and acceptable method for diagnosing precancerous lesions of the oesophagus, and this technique also showed promising accuracy data, based on a small number of outcomes. This approach deserves further consideration from us in ESCC-screening programmes in high-risk areas including Northern Iran.

Change history

09 December 2014

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Abedi-Ardekani B, Kamangar F, Hewitt SM, Hainaut P, Sotoudeh M, Abnet CC, Taylor PR, Boffetta P, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM (2010) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure in oesophageal tissue and risk of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in north-easternIran. Gut 59: 1178–1183.

Abnet CC, Kamangar F, Islami F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Brennan P, Aghcheli K, Merat S, Pourshams A, Marjani HA, Ebadati A, Sotoudeh M, Boffetta P, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM (2008) Tooth loss and lack of regular oral hygiene are associated with higher risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 3062–3068.

Aghcheli K, Marjani H, Nasrollahzadeh D, Islami F, Shakeri R, Sotoudeh M, Abedi-Ardekani B, Ghavamnasiri MR, Razaei E, Khalilipour E, Mohtashami S, Makhdoomi Y, Rajabzadeh R, Merat S, Sotoudehmanesh R, Semnani S, Malekzadeh R (2011) Prognostic factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma—a population-based study in Golestan Province, Iran, a high incidence area. PLoS One 6: e22152.

Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Hutfless SM, Wang Y, David S, Cheng Y, Twaddell WS, Latt NL, Shin EJ, Wang LD, Wang L, Yang W, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Meltzer SJ (2012) Comparative genomic analysis of esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2: 899–905.

Akbari M, Malekzadeh R, Lepage P, Roquis D, Sadjadi A, Aghcheli K, Yazdanbod A, Shakeri R, Bashiri J, Sotoudeh M, Pourshams A, Ghadirian P, Narod S (2011) Mutations in Fanconi anemia genes and the risk of esophageal cancer. Hum Genet 129: 573–582.

Akbari MR, Malekzadeh R, Nasrollahzadeh D, Amanian D, Islami F, Li S, Zandvakili I, Shakeri R, Sotoudeh M, Aghcheli K, Salahi R, Pourshams A, Semnani S, Boffetta P, Dawsey SM, Ghadirian P, Narod SA (2007) Germline BRCA2 mutations and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 27: 1290–1296.

Bergman JJ, Zhang YM, He S, Weusten B, Xue L, Fleischer DE, Lu N, Dawsey SM, Wang GQ (2011) Outcomes from a prospective trial of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation ofearly squamous cell neoplasia of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 74: 1181–1190.

Das A (2010) Tumors of the esophagus. In Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management, Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt LJ, (eds) 9th edn Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Dawsey SM, Fleischer DE, Wang GQ, Zhou B, Kidwell JA, Lu N, Lewin KJ, Roth MJ, Tio TL, Taylor PR (1998) Mucosal iodine staining improves endoscopic visualization of squamous dysplasia and squamouscell carcinoma of the esophagus in Linxian, China. Cancer 83: 220–231.

Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Liu FS, Wang GQ, Shen Q (1994a) Esophageal morphology from Linxian, China. Squamous histologic findings in 754 patients. Cancer 73: 2027–2037.

Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Wang GQ, Liu FS, Nieberg RK, Yu Y, Li JY, Blot WJ, Li B, Taylor PR (1994b) Squamous esophageal histology and subsequent risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. A prospective follow-up study from Linxian, China. Cancer 74: 1686–1692.

Dowlatshahi K, Daneshbod A, Mobarhan S (1978) Early detection of cancer of oesophagus along Caspian Littoral: Report of a Pilot Project. Lancet 1: 125–126.

Etemadi A, Abnet CC, Golozar A, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM (2012) Modeling the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and squamous dysplasia in a high risk area in Iran. Arch Iran Med 15: 18–21.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F (2013) GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France.

Ghasemi-Kebria F, Roshandel G, Semnani S, Shakeri R, Khoshnia M, Naeimi-Tabiei M, Merat S, Malekzadeh R (2013) Marked increase in the incidence rate of esophagealadenocarcinoma in a high-risk area for esophageal cancer. Arch Iran Med 16: 320–323.

Islami F, Kamangar F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Aghcheli K, Sotoudeh M, Abedi-Ardekani B, Merat S, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Semnani S, Sepehr A, Wakefield J, Moller H, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM, Boffetta P, Malekzadeh R (2009a) Socio-economic status and oesophageal cancer: results from a population-based case-control study in a high-risk area. Int J Epidemiol 38: 978–988.

Islami F, Kamangar F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Moller H, Boffeta P, Malekzadeh R (2009b) Oesophageal cancer in Golestan Province, a high-incidence area in northern Iran - a review. Eur J Cancer 45: 3156–3165.

Islami F, Pourshams A, Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Fahimi S, Shakeri R, Abedi-Ardekani B, Merat S, Vahedi H, Semnani S, Abnet CC, Brennan P, Moller H, Saidi F, Dawsey SM, Malekzadeh R, Boffetta P (2009c) Tea drinking habits and oesophageal cancer in a high risk area in northern Iran: population based case-control study. BMJ 338: b929.

Kadri SR, Lao-Sirieix P, O'Donovan M, Debiram I, Das M, Blazeby JM, Emery J, Boussioutas A, Morris H, Walter FM, Pharoah P, Hardwick RH, Fitzgerald RC (2010) Acceptability and accuracy of a non-endoscopic screening test for Barrett's oesophagus in primary care: cohort study. BMJ 341: c4372.

Kamangar F, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM, Saidi F (2007) Esophageal cancer in Northeastern Iran: a review. Arch Iran Med 10: 70–82.

Lao-Sirieix P, Boussioutas A, Kadri SR, O'Donovan M, Debiram I, Das M, Harihar L, Fitzgerald RC (2009) Non-endoscopic screening biomarkers for Barrett's oesophagus: from microarray analysis to the clinic. Gut 58: 1451–1459.

Lao-Sirieix P, Fitzgerald RC (2012) Screening for oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9: 278–287.

Lazarus C, Jaskiewicz K, Sumeruk RA, Nainkin J (1992) Brush cytology technique in the detection of oesophageal carcinoma in the asymptomatic, high risk subject; a pilot survey. Cytopathology 3: 291–296.

Ludeman L, Shepherd NA (2005) Serosal involvement in gastrointestinal cancer: Its assessment and significance. Histopathology 47: 123–131.

Mahboubi E, Kmet J, Cook PJ, Day NE, Ghadirian P, Salmasizadeh S (1973) Oesophageal cancer studies in the Caspian Littoral of Iran: the Caspian cancer registry. Br J Cancer 28: 197–214.

Nabeya K, Onozawa K, Ri S (1979) Brushing cytology with capsule for esophageal cancer. Chir Gastroenterol 13: 101–107.

Pan QJ, Roth MJ, Guo HQ, Kochman ML, Wang GQ, Henry M, Wei WQ, Giffen CA, Lu N, Abnet C, Hao CQ, Taylor P, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM (2008) Cytologic detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions using ballon samplers and liquid-based cytology in asymptomatic adults in Linxian, China. Acta Cytol 52: 14–23.

Pech O, May A, Gossner L, Rabenstein T, Manner H, Huijsmans J, Vieth M, Stolte M, Berres M, Ell C (2007) Curative endoscopic therapy in patients with early esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Endoscopy 39: 30–35.

Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, Olivier M (2007) Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat 28: 622–629.

Pourshams A, Khademi H, Malekshah AF, Islami F, Nouraei M, Sadjadi AR, Jafari E, Rakhshani N, Salahi R, Semnani S (2010) Cohort Profile: The Golestan Cohort Study—a prospective study of oesophageal cancer in northern Iran. Int J Epidemiol 39: 52–59.

Roshandel G, Khoshnia M, Sotoudeh M, Merat S, Etemadi A, Nikmanesh A, Norouzi A, Pourshams A, Poustchi H, Semnani S, Ghasemi-Kebria F, Noorbakhsh R, Abnet C, Dawsey SM, Malekzadeh R (2014) Endoscopic screening for precancerous lesions of the esophagus in a high risk area in Northern Iran. Arch Iran Med 17: 246–252.

Roshandel G, Sadjadi A, Aarabi M, Khademi H, Keshtkar A, Sedaghat SM, Nouraei M, Semnani S, Malekzadeh R (2012a) Cancer incidence in Golestan: report of an ongoing population-based cancer registry in Iran, 2004-2008. Arch Iran Med 15: 196–200.

Roshandel G, Semnani S, Malekzadeh R (2012b) None-endoscopic screening for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma- a review. Middle East J Dig Dis 4: 111–124.

Roth MJ, Liu S-F, Dawsey SM, Zhou B, Copeland C, Wang G-Q, Solomon D, Baker SG, Giffen CA, Taylor PR (1997) Cytologic detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions using balloon and sponge samplers in asymptomatic adults in Linxian, China. Cancer 80: 2047–2059.

Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Flejou JF, Geboes K, Hattori T, Hirota T, Itabashi M, Iwafuchi M, Iwashita A, Kim YI, Kirchner T, Klimpfinger M, Koike M, Lauwers GY, Lewin KJ, Oberhuber G, Offner F, Price AB, Rubio CA, Shimizu M, Shimoda T, Sipponen P, Solcia E, Stolte M, Watanabe H, Yamabe H (2000) The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 47: 251–255.

Semnani S, Sadjadi A, Fahimi S, Nouraie M, Naeimi M, Kabir J, Fakheri H, Saadatnia H, Ghavamnasiri MR, Malekzadeh R (2006) Declining incidence of esophageal cancer in the Turkmen Plain, eastern part of the Caspian Littoral of Iran: a retrospective cancer surveillance. Cancer Detect Prev 30: 14–19.

Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, Raab S, Sherman M, Wilbur D, Wright T Jr (2002) The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 287: 2114–2119.

Taylor PR, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM (2013) Squamous dysplasia—the precursor lesion for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22: 540–552.

Wang GQ, Abnet CC, Shen Q, Lewin KJ, Sun XD, Roth MJ, Qiao YL, Mark SD, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Dawsey SM (2005) Histological precursors of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a 13 year prospective follow up study in a high risk population. Gut 54: 187–192.

Wei WQ, Abnet CC, Lu N, Roth MJ, Wang GQ, Dye BA, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Albert P, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM (2005) Risk factors for oesophageal squamous dysplasia in adult inhabitants of a high risk region of China. Gut 54: 759–763.

Yang S, Wu S, Huang Y, Shao Y, Chen XY, Xian L, Zheng J, Wen Y, Chen X, Li H, Yang C (2012) Screening for oesophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12: Cd007883.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Miss Kor, Mrs Ghasemi-Kebria, Mrs Noorbakhsh, Dr Sharifi, Dr Khalilipour, Dr Abaie, Mr Yolmeh, Mr Ataie, Mrs Nasi and Mrs Mohammadi for their valuable work in data collection and sample processing. This study was supported by the Digestive Disease Research Institute (DDRI) affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) as a thesis for obtaining a PhD degree; the Golestan Research Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (GRCGH) affiliated with Golestan University of Medical Sciences (GOUMS); and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Roshandel, G., Merat, S., Sotoudeh, M. et al. Pilot study of cytological testing for oesophageal squamous cell dysplasia in a high-risk area in Northern Iran. Br J Cancer 111, 2235–2241 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.506

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.506

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Improving outcomes in patients with oesophageal cancer

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Evaluating the Correlation Between the Survival Rate of Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Expression of p53 and Cyclin D1 Biomarkers Along with Other Prognostic Factors

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2018)

-

Sponge Sampling with Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization as a Screening Tool for the Early Detection of Esophageal Cancer

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2017)