Abstract

Background:

A phase III trial demonstrated an overall survival advantage with the addition of vinflunine to best supportive care (BSC) in platinum-refractory advanced urothelial cancer. We subsequently examined the impact of an additional 2 years of survival follow-up and evaluated the influence of first-line platinum therapy on survival.

Methods:

The 357 eligible patients from the phase III study were categorised into two cohorts depending on prior cisplatin treatment: cisplatin or non-cisplatin. Survival was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results:

The majority had received prior cisplatin (70.3%). Survival was higher in the cisplatin group (HR: 0.76; CI 95% 0.58–0.99; P=0.04) irrespective of treatment arm. Multivariate analysis including known prognostic factors (liver involvement, haemoglobin, performance status) and prior platinum administration did not show an independent effect of cisplatin. Vinflunine reduced the risk of death by 24% in the cisplatin-group (HR: 0.76; CI 95% 0.58–0.99; P=0.04) and by 35% in non-cisplatin patients (HR: 0.65; CI 95% 0.41–1.04; P=0.07).

Interpretation:

Differences in prognostic factors between patients who can receive prior cisplatin and those who cannot may explain the survival differences in patients who undergo second line therapy. Prior cisplatin administration did not diminish the subsequent benefit of vinflunine over BSC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

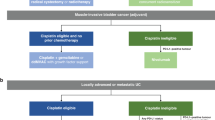

While metastatic urothelial cancer (UC) is generally sensitive to chemotherapy, the majority of patients will succumb to this disease. Cisplatin-based regimens such as gemcitabine plus cisplatin (GC) or methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) increase survival and remain the cornerstone of first-line treatment (von der Maase et al, 2000; Sternberg et al, 2001; von der Maase et al, 2005). In patients unfit to receive cisplatin, regimens containing gemcitabine, carboplatin, or taxane are often utilised (Dreicer et al, 2004; De Santis et al, 2012).

Vinflunine is a microtubule inhibitor that elicits more potent in vivo antitumor activity than other members of the vinca alkaloid family such as paclitaxel or docetaxel (Lobert et al, 1998; Jean-Decoster et al, 1999; Ngan et al, 2001). Its weaker binding to tubulin translates to potentially less neurotoxicity. Two phase II studies in platinum refractory advanced UC patients suggested intriguing preliminary efficacy with an objective response rate of 16–18%, a median duration of response of 6–9 months, and a median progression-free survival (PFS) around 3 months (Culine et al, 2006; Vaughn et al, 2009). These studies led to a phase III randomised controlled trial executed mostly in Europe, where vinflunine plus best supportive care (BSC) was compared with BSC alone in 370 patients who had experienced progression during or after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (Bellmunt et al, 2009). A non-statistically significant 2-month increase in the median overall survival (OS) from 4.6 months with BSC to 6.9 months with the addition of vinflunine (HR 0.88; 95% CI, 0.69–1.12, P=0.29 (L00070 IN 302 trial) was observed. It is important to note that the ITT analysis may have been clouded by the inclusion of patients with protocol deviations. A pre-planned analysis in eligible patients that excluded the deviation cases confirmed statistical significance, with the median OS for vinflunine plus BSC being 6.9 months compared with BSC alone at 4.3 months (P=0.04) and led to its approval by the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) (Bellmunt et al, 2009).

During the EMEA assessment of the vinflunine submission, the question of whether prior platinum therapy had an impact on OS was raised. This query stemmed from a subgroup analysis of OS stratified by prior cisplatin administration in the ITT population (November 2006 cutoff date). This analysis suggested that the degree of benefit elicited by vinflunine was lower in the cisplatin group with a 9% decrease in the risk of death compared to 25% in the non-cisplatin group (HR=0.91 vs HR=0.75). These results led some to hypothesise that vinflunine might only be effective in patients who had not received prior cisplatin. These findings spurred us to perform an updated analysis that adjusted for an additional 2-year survival follow-up period and incorporated a test for interaction to evaluate the impact of the first-line platinum therapy on overall survival when vinflunine is administered in the second-line setting.

Methods

Patient population

The analysis focused on the 357 eligible patients with UC who were enroled onto the phase III randomised controlled trial, which compared vinflunine plus BSC with BSC alone (L00070 IN 302), with an updated median follow-up of now 45.4 months (Bellmunt et al, 2009). The ‘eligible’ population is distinct from the ITT population, as it removes 13 patients who had major protocol deviations as detailed in the original report. The demographics of this patient population have been previously described and were generally well balanced, with the exception of a 10% difference in worse performance status (PS) favouring the control arm. Random assignment in the Phase III study was stratified by study site and platinum-refractory status but not by PS, which is now recognised as an important prognostic factor (Bajorin et al, 1999; Bellmunt et al, 2010). Pretreatment clinical and analytic factors were prospectively recorded. Type and setting of prior therapy in both arms were also prospectively recorded. For this current study, the eligible population was split into the following two subsets: cisplatin (patients with prior cisplatin administration) and non-cisplatin (patients without prior cisplatin administration) irrespective of the phase III treatment arm they were on in order to study the impact of prior platinum therapy. Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee approvals from each institution were obtained as part of the prospective intervention trial.

Statistical analysis

Survival was measured from the date of random assignment to either the date of death or the last follow-up. For this analysis, mature updated survival data were used. The cutoff date was 30 November 2008. This update represented a significantly longer median follow-up period of 45.5 months compared with 22.1 months in the initial analysis. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the effect of treatment on OS. The distributions of OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method for each treatment group and were compared between treatments by stratified log-rank tests. Subgroup analysis was conducted according to the prior platinum administration. An interaction term between study treatment and prior platinum therapy evaluated whether the association between study treatment and risk of death reduction differed according to the prior platinum therapy. In addition, Cox multivariate analyses were performed to take into account important prognostic factors that have been previously identified: haemoglobin (<10 g dl−1 vs ⩾10 g dl−1), ECOG PS (<1 vs ⩾1), and liver metastasis (present vs absent).

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 357 patients enroled on the second-line vinflunine trial, 251 received prior cisplatin (70.3%) and 106 did not (29.7%). As expected, the most common first-line cisplatin-based regimens were GC (48.5%) and MVAC (12.9%) (Supplementary Online Material Table 1). The most common regimens administered in the first-line setting for the non-cisplatin group were carboplatin and gemcitabine.

Overall, patients in the cisplatin group tended to be younger (median age 63 vs 69 years) and have better renal function (median CrCl: 64 vs 55 cc min−1) at the initiation of second-line vinflunine (Table 1). They had better prognostic characteristics with less frequent liver involvement (25% for cisplatin vs 43% for non-cisplatin-treated patients, P=0.0007) and enhanced PS as measured by WHO-PS ⩾1 (66% for cisplatin vs 76% for non-cisplatin, P=0.047) (Table 1).

Survival

When evaluating eligible patients on the trial regardless of whether they received vinflunine or only BSC, patients who were treated with first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy had improved overall survival compared with patients who did not receive first-line cisplatin (Figure 1). Prior cisplatin reduced the risk of death by 23% compared with no prior cisplatin (stratified log-rank test P=0.0294). However, this significance did not persist in multivariate analysis when adjusted for known important prognostic factors such as liver involvement, PS, and haemoglobin (Table 2).

Compared with the initial subgroup analysis of OS according to prior cisplatin administration in the ITT population (November 2006 cutoff date, Table 3), in the updated analysis of the eligible (modified ITT) population, vinflunine now significantly reduced the risk of death by 24% with a median gain of 2.2 months in the median OS compared with BSC in patients who received prior cisplatin (P=0.04, Table 4). In patients without prior cisplatin exposure, an increase in 2.4 months in the median OS was obtained with vinflunine, reducing the risk of death by 35% (P=0.07). The Kaplan–Meier curves in the cisplatin group (Figure 2) and in the non-cisplatin group (Figure 3) illustrate the benefit of vinflunine in terms of survival irrespective of prior cisplatin therapy.

In order to ensure that the risk of death reduction associated with vinflunine is the same whether or not patients received prior cisplatin, a statistical test for interaction was conducted (Table 5). This test was not significant (P=0.63), confirming that the effect of vinflunine on survival is not diminished by prior cisplatin administration. Thus, the best estimate for vinflunine effect adjusted on prior cisplatin use is obtained with a model, which includes only the main potential effects of treatment group and prior cisplatin (Table 6) (HR 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58–0.93, P=0.009).

Discussion

Subgroup analysis during the EMEA assessment of the vinflunine submission suggested that the degree of benefit elicited by vinflunine was lower in the cisplatin group with a 9% vs 25% decrease in the risk of death (0.91 vs 0.75 in the non-cisplatin group, Table 3). These results suggested that the administration of vinflunine might only be effective in patients who had not received prior cisplatin. With its longer followup time, our updated analysis dismisses this theory but validates the generally accepted belief that patients who are eligible for cisplatin have better outcomes. Regardless of whether patients received vinflunine or only BSC in the second-line setting, patients who were treated with first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy had improved overall survival (Figure 1). In all patients, prior cisplatin use significantly reduced the risk of death by 23% compared with no prior cisplatin use (P=0.04). These results suggest that the previous therapy with cisplatin is important for survival in the second-line setting irrespective of the actual second-line therapy, in the case either vinflunine or BSC. However, the possibility of selection bias should be stressed; in order to receive cisplatin in the first place, patients are generally relatively ‘healthier’ with good PS and adequate end organ function. The established prognostic factors for improved survival include good PS and absence of visceral metastases or anaemia (Bajorin et al, 1999; Bellmunt et al, 2010). In a retrospective review of seven prospective second-line phase II trials, Sonpavde et al (2013) further observed that shorter time from prior cisplatin therapy to start of subsequent therapy also portended worse survival in the second-line setting. In the phase III vinflunine trial, patients who had received prior cisplatin had overall more favourable prognostic criteria (Table 1). Further, multivariate analysis adjusting for the validated prognostic factors of liver involvement, PS, and haemoglobin confirmed that these factors were more important drivers in the survival improvement than the prior cisplatin use (Table 2). In the study by Sonpavde et al (2013), despite a favourable trend, time from prior cisplatin therapy did not bear out as independently significant for OS (P=0.066) in multivariable analysis that included PS >0, presence of liver metastases, and haemoglobin <10. Taken together, these results validate that metastases to the liver, poor PS, and anaemia remain the most important criteria for survival in metastatic platinum-pretreated urothelial carcinoma. Patients with the triumvariate are less likely to receive cisplatin-based therapy and as such the overall ability to get cisplatin may be a reflection of the presence of these unfavourable markers or more aggressive disease.

Our secondary objective was to assess whether patients who had received prior cisplatin specifically benefit from second-line vinflunine as the EMEA’s initial assessment had suggested lower efficacy in these patients. Our updated analysis revealed that vinflunine’s benefit was not restricted to the non-cisplatin patients (Table 4). The reduction in the risk of death obtained with vinflunine was similar in the cisplatin and non-cisplatin arms. In all patients who received first-line cisplatin, vinflunine elicited a median 2.2 month increase in survival compared with patients who received BSC (6.9 vs 4.7 months, HR 0.76, P=0.04). This benefit equates to a significant reduction in the risk of death by 24% compared with BSC. Similarly, in patients who did not receive prior cisplatin, vinflunine increased OS by a median of 2.4 months (5.8 vs 3.4 months, HR 0.65, P=0.07), signifying a 35% reduction in the risk of death compared with BSC. Although the difference in OS in the non-cisplatin group did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.07), likely due to a lack of power given the small patient numbers in this cohort, the trend is clearly in favour of vinflunine. Finally, the statistical test for interaction between prior cisplatin administration and treatment arm (vinflunine vs BSC) is not significant, confirming that the effect of vinflunine on the risk of death reduction is similar regardless of prior platinum administration. As the test for interaction was not significant, the best estimate for the risk of death reduction with second-line vinflunine across the whole eligible population is 22% (HR=0.78; 95% CI, 0.61–0.99; P=0.04).

It should be highlighted that this study enrolled patients in whom all the first-line chemotherapies were delivered in the metastatic setting. However, as the majority were able to receive cisplatin, the patient population enroled in the phase III second-line vinflunine trial may have been a relatively healthier patient population with likely better PS, adequate renal function, and less comorbidities. Not surprisingly, despite that the effect of vinflunine remains the same in terms of reduction in the risk of death, the observed OS was lower in the patients who had not received prior cisplatin. This observation reflects that patients unable to receive cisplatin likely have a worse prognosis because of a more aggressive disease biology or other host factors and comorbidities that outweigh the efficacy of the specific second-line therapy they receive. The absence of a significant difference in the HRs (0.78 vs 0.68, Table 4) supports this assertion.

This study is limited by its post-hoc nature and limitations inherent to any retrospective analysis. Although subset analysis can be informative, it is the only hypothesis generating, and these results require future validation. Perhaps most importantly, whereas vinflunine is approved in Europe, it is not approved in the United States, and, thus, the impact of these results are limited in applicability outside Europe.

Conclusions

This analysis confirms that vinflunine increases survival irrespective of prior cisplatin administration. Thus, we conclude that cisplatin administration in the first-line setting should not direct the choice of vinflunine in the second-line setting. Previous cisplatin use correlates with improved survival; however, upon further multivariate analysis, this improvement may be best attributed to those patients having more favourable prognostic criteria such as better PS and absence of visceral metastasis or anaemia. Vinflunine remains the only agent to demonstrate an improvement in OS in the second-line treatment of UC and should be accepted as the standard of care with the recognition that the median 2-month survival benefit is modest, and the investigation of novel agents that target driver pathways is imperative.

Change history

12 November 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Bajorin DF, Dodd PM, Mazumdar M, Fazzari M, McCaffrey JA, Scher HI, Herr H, Higgins G, Boyle MG (1999) Long-term survival in metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma and prognostic factors predicting outcome of therapy. J Clin Oncol 17 (10): 3173–3181.

Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, Schutz FA, Salhi Y, Winquist E, Culine S, von der Maase H, Vaughn DJ, Rosenberg JE (2010) Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol 28 (11): 1850–1855.

Bellmunt J, Theodore C, Demkov T, Komyakov B, Sengelov L, Daugaard G, Caty A, Carles J, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Karyakin O, Delgado FM, Hurteloup P, Winquist E, Morsli N, Salhi Y, Culine S, von der Maase H (2009) Phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone after a platinum-containing regimen in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. J Clin Oncol 27 (27): 4454–4461.

Culine S, Theodore C, De Santis M, Bui B, Demkow T, Lorenz J, Rolland F, Delgado FM, Longerey B, James N (2006) A phase II study of vinflunine in bladder cancer patients progressing after first-line platinum-containing regimen. Br J Cancer 94 (10): 1395–1401.

De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Mead G, Kerst JM, Leahy M, Maroto P, Gil T, Marreaud S, Daugaard G, Skoneczna I, Collette S, Lorent J, de Wit R, Sylvester R (2012) Randomized phase II/III trial assessing gemcitabine/carboplatin and methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine in patients with advanced urothelial cancer who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy: EORTC study 30986. J Clin Oncol 30 (2): 191–199.

Dreicer R, Manola J, Roth BJ, See WA, Kuross S, Edelman MJ, Hudes GR, Wilding G (2004) Phase III trial of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced carcinoma of the urothelium. Cancer 100 (8): 1639–1645.

Jean-Decoster C, Brichese L, Barret JM, Tollon Y, Kruczynski A, Hill BT, Wright M (1999) Vinflunine, a new vinca alkaloid: cytotoxicity, cellular accumulation and action on the interphasic and mitotic microtubule cytoskeleton of PtK2 cells. Anticancer Drugs 10 (6): 537–543.

Lobert S, Ingram JW, Hill BT, Correia JJ (1998) A comparison of thermodynamic parameters for vinorelbine- and vinflunine-induced tubulin self-association by sedimentation velocity. Mol Pharmacol 53 (5): 908–915.

Ngan VK, Bellman K, Hill BT, Wilson L, Jordan MA (2001) Mechanism of mitotic block and inhibition of cell proliferation by the semisynthetic Vinca alkaloids vinorelbine and its newer derivative vinflunine. Molr Pharmacol 60 (1): 225–232.

Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Fougeray R, Choueiri TK, Qu AQ, Vaughn DJ, Niegisch G, Albers P, James ND, Wong YN, Ko YJ, Sridhar SS, Galsky MD, Petrylak DP, Vaishampayan UN, Khan A, Vogelzang NJ, Beer TM, Stadler WM, O'Donnell PH, Sternberg CN, Rosenberg JE, Bellmunt J (2013) Time from prior chemotherapy enhances prognostic risk grouping in the second-line setting of advanced urothelial carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of pooled, prospective phase 2 trials. Eur Urol 63 (4): 717–723.

Sternberg CN, de Mulder PH, Schornagel JH, Theodore C, Fossa SD, van Oosterom AT, Witjes F, Spina M, van Groeningen CJ, de Balincourt C, Collette L (2001) Randomized phase III trial of high-dose-intensity methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) chemotherapy and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor versus classic MVAC in advanced urothelial tract tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Protocol no. 30924. J Clin Oncol 19 (10): 2638–2646.

Vaughn DJ, Srinivas S, Stadler WM, Pili R, Petrylak D, Sternberg CN, Smith DC, Ringuette S, de Wit E, Pautret V, George C (2009) Vinflunine in platinum-pretreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: results of a large phase 2 study. Cancer 115 (18): 4110–4117.

von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, Bodrogi I, Albers P, Knuth A, Lippert CM, Kerbrat P, Sanchez Rovira P, Wersall P, Cleall SP, Roychowdhury DF, Tomlin I, Visseren-Grul CM, Conte PF (2000) Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol 18 (17): 3068–3077.

von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, Ricci S, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, Zimmermann A, Arning M (2005) Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 23 (21): 4602–4608.

Acknowledgements

The original phase III study was supported by Pierre Fabre but this retrospective study was not. Employees of Pierre Fabre (RF, YS) had a role in the study design and interpretation of the results. The corresponding author (JB) had full access to all the data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author contributions

LH, RF, TKC, and JB formed the core writing team for the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study design, collection, and assembly of data, or data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RF: Statistician, employee of Pierre Fabre, YS: Statistician, employee of Pierre Fabre, JB: Delivered lectures on behalf of and received consultant fees from Pierre Fabre. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Harshman, L., Fougeray, R., Choueiri, T. et al. The impact of prior platinum therapy on survival in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer receiving vinflunine. Br J Cancer 109, 2548–2553 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.617

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.617