Abstract

Background:

The detection of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) has been linked with poor prognosis in advanced breast cancer. Relatively few studies have been undertaken to study the clinical relevance of CTCs in early-stage breast cancer.

Methods:

In a prospective study, we evaluated CTCs in the peripheral blood of 82 early-stage breast cancer patients. Control groups consisted of 16 advanced breast cancer patients and 45 healthy volunteers. The CTC detection was performed using ErbB2/EpCAM immunomagnetic tumour cell enrichment followed by multimarker quantitative PCR (QPCR). The CTC status and common clinicopathological factors were correlated to relapse-free, breast cancer-related and overall survival.

Results:

Circulating tumour cells were detected in 16 of 82 (20%) patients with early-stage breast cancer and in 13 out of 16 (81%) with advanced breast cancer. The specificity was 100%. The median follow-up time was 51 months (range: 17–60). The CTC positivity in early-stage breast cancer patients resulted in significantly poorer relapse-free survival (log rank test: P=0.003) and was an independent predictor of relapse-free survival (multivariate hazard ratio=5.13, P=0.006, 95% CI: 1.62–16.31).

Conclusion:

The detection of CTCs in peripheral blood of early-stage breast cancer patients provided prognostic information for relapse-free survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Breast cancer mortality rates have declined over the last decade because of better screening and improved diagnostic techniques and treatments; however, it still remains the main cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide (Levi et al, 2005). Approximately one-third of all women with primary breast cancer will develop metastatic disease (Rosen et al, 1989; Fisher et al, 2002), whereby the risk of relapse is strongly related to lymph node involvement, tumour size, grade at diagnosis (Fitzgibbons et al, 2000), lymphatic and/or vascular invasion, hormone receptor status and presence of HER2 overexpression (Pinder et al, 1994). More recently, the risk of metastasis has also been shown to correlate well with prognostic gene expression profiles (van de Vijver et al, 2002; Paik et al, 2004; Wang et al, 2005).

The detection of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) has been correlated to poor progression-free survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer (Cristofanilli et al, 2004, 2005). For CTCs, starting with peripheral blood as sampling material is advantageous for the patient, as it is much less invasive to obtain than a tumour biopsy. Moreover, the accessibility enables sequential sampling during therapy. In patients with early-stage breast cancer, the detection of CTCs or disseminated tumour cells (DTCs) in the blood and/or bone marrow has also been found to be an independent negative prognostic factor for disease recurrence and overall survival (Mansi et al, 1999; Pantel et al, 1999; Braun et al, 2000). However, relatively few studies have been undertaken to investigate the prognostic significance of CTCs in non-metastatic breast cancer patients (Daskalaki et al, 2009; Muller and Pantel, 2009; Xenidis et al, 2009), perhaps because of the high assay sensitivity and specificity required for such studies as a result of the relative rarity of CTCs.

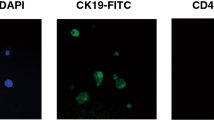

Previously, we designed a quantitative PCR (QPCR)-based assay that utilises a panel of four tumour marker genes for the detection of occult tumour cells in the peripheral blood of metastatic breast cancer patients. The tumour marker genes had been selected after a systematic search for genes that are highly expressed in breast cancer, but not in the cellular constituents of peripheral blood (Bosma et al, 2002). Our test showed a sensitivity of 31% and a specificity of 100% in metastatic breast cancer patients and predicted for a worse progression-free and overall survival (Weigelt et al, 2003). Next, we optimised the assay's sensitivity by introducing a dual-antigen immunomagnetic tumour cell enrichment procedure before marker gene quantitation and by refining the panel of marker genes as follows: cytokeratin 19 (CK19), human secretory protein p1.B (p1B), human epithelial glycoprotein (EpCAM; here: EGP) and mammaglobin (MmGl) (Molloy et al, 2008). In spiking experiments, we showed that our assay has the sensitivity of detecting as few as 10 tumour cells from a background of 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Molloy et al, 2008).

In this study, we used our improved platform for CTC detection in a prospective cohort of patients with early-stage breast cancer, in an effort to detect the presence of CTCs at diagnosis. These data were then correlated to disease outcome. In addition, we used our platform in two control groups, being advanced breast cancer patients and healthy volunteers.

Materials and methods

The methods and data described herein adhere to the REMARK criteria for the reporting of tumour marker prognostic studies (McShane et al, 2006).

Patient selection and peripheral blood sampling

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the Netherlands Cancer Institute. Women presenting at the outpatient clinic of The Netherlands Cancer Institute with clinically stage I–III breast cancer were invited to participate between May 2005 and May 2006. Patients with a history of previous malignancy and patients with disseminated breast cancer or active infection were excluded. Type of surgery, locoregional radiotherapy and adjuvant systemic therapy was left to the treating physician, following nationwide standardised protocols.

From all patients, 8.0 ml whole blood samples were collected during routine preoperative blood sampling in tubes containing a Ficoll-Hypaque density fluid separated by a polyester gel barrier from a sodium citrate anticoagulant (Vacutainer CPT, Beckton Dickinson, Breda, The Netherlands). Mononuclear cells, including any tumour cells present, were isolated from blood samples within 24 h of collection.

Selection of advanced breast cancer patients and healthy volunteer control subjects

Patients with advanced breast cancer (M1 disease, according to the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer criteria) were included as ‘positive controls’ as the majority were expected to have CTCs. They were invited to participate if they were between treatments or soon to start subsequent palliative treatment modality. Also, a third group of healthy, female anonymous control subjects, who were randomly selected from hospital staff, were asked to participate. Blood sample collection and preparation were performed as described above.

Additional analyses: effect of frozen storage and the value of repeated sampling after therapy

In order to assess the effect of frozen storage, samples of a subgroup of patients and healthy volunteers were collected in duplicate. Mononuclear fractions were isolated and one sample was analysed directly and the other was supplemented with ‘freezing medium’ (RPMI-1640 medium with L-glutamine (Gibco, Breda, The Netherlands) containing 10% dimethylsulphoxide, (DMSO; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco) and stored in liquid nitrogen. After 3 months, the frozen pellets were thawed and enriched as described above.

In order to gain insight into the additional value of our assay after therapy, peripheral blood samples were collected between October 2008 and February 2009, after written informed consent, from a subset of patients who continued to visit the outpatient clinic and had remained disease free.

Tumour cell enrichment

Tumour cells were separated from PBMCs using anti-EpCAM (CD326) (clone HEA-125) and anti-ErbB2 (HER2) Micro Beads (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec, Utrecht, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, beads were incubated with the PBMCs for 30 min at 4 °C, after which labelled cells were collected on a magnetic separation column. After removal of the column from the magnetic field, the retained EpCAM+ and/or ErbB2+ cells were eluted, and stored at −70 °C in lysis buffer (5 M Guanidine thiocyanate (Merck), pH 6.8, 0.05 M Tris (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 0.02 M EDTA and 1.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany)) until mRNA isolation and cDNA synthesis.

mRNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

mRNA was precipitated from the cell lysate and dissolved in lysis buffer from the μMACS One-step cDNA kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Oligo(dT) Micro Beads were added and the mixture placed onto the μMACS column in the thermo MACS Separator. Next, cDNA synthesis was carried out as per the manufacturer's instructions, with an additional elution with 20 μl of elution buffer, resulting in a total volume of 70 μl.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR primers (Sigma Genosys, Cambridge, UK) and 5′-fluorescently FAM-labelled TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands) were designed using the Perkin Elmer Primer Express software (PE, Foster City, CA, USA) based on the published sequences of CK19, p1B, EGP and MmGl as previously described (Molloy et al, 2008) (Table 1). All primers were designed to be intron-spanning to preclude amplification of genomic DNA. Commercially available primers and probes for the ‘housekeeping’ genes β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Applied Biosystems) were also used.

Serially diluted cDNA synthesised from the amplified RNA of 82 snap frozen breast cancer tissues was used to generate standard curves for control and marker gene expression. For all cDNA dilutions, fluorescence was detected from 0 to 50 PCR cycles for the control and marker genes in singleplex reactions, which allowed the deduction of the CT value for each product. The CT value (threshold cycle) is the PCR cycle at which a significant increase in fluorescence is detected because of the exponential accumulation of PCR products and is represented in arbitrary units (TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix Protocol, Applied Biosystems) (Bieche et al, 1999). The expression of each tumour marker gene was calculated relative to β-actin in each sample, and the second ‘housekeeping’ gene, GAPDH, was used only to confirm reaction efficiency. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Quality control measures for the PCR reactions included the addition of a genomic DNA control and a non-template control.

Clinical follow-up

Of every patient, up to 1 February 2010, regular clinical follow-up was recorded in the patient file and the Institute's Medical Registry. This included evaluation of relapse of disease, breast cancer-related death and death by other causes. Relapse of disease was defined as the development of either local or distant breast cancer metastases. In case of relapse, the date of diagnosis was recorded. In the absence of relapse, the date of the last visit to the outpatient clinic within a year before February 2010 was recorded as last follow-up date. When needed, for example, when the last follow-up was longer than a year before or further treatment took place in another hospital, information was verified with the general physician and the last visit there was recorded as last follow-up. One patient without relapse refused further participation after 44 months of follow-up, being longer than a year before February 2010. This date was recorded as last follow-up and censored for further analysis.

Statistics

Analyses were carried out using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were performed at the 5% level of significant difference. Differences of rates between groups were compared with either the two-sided Fisher's exact test or Pearson's χ2-test or, for ordinal variables, χ2-test for trend. Differences between groups with continuous variables were tested by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test. The quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) score function was calculated from the expression data of four marker genes (CK19, p1B, EGP and MmGl) as previously described (Hand, 1992; Bosma et al, 2002). The QDA is a statistical approach to find the combination of quadratic and linear functions of variables (in this case marker genes), which leads to the optimal separation between groups (in this case, advanced breast cancer patients and healthy volunteers). It is a generalisation of the more familiar Fisher's linear discrimination analysis (LDA), which allows only linear functions (Weigelt et al, 2004). The highest value of the healthy control group was set as threshold value for positivity (QDA value > threshold: ‘QDA-positive’) and negativity (for QDA value ⩽ threshold: ‘QDA-negative’) of other samples. This threshold was fixed for any future study. QDA positivity indicated the presence of tumour cells in a sample and, conversely, QDA negativity indicated their absence. Patients with a QDA-positive or QDA-negative test from their blood sample were defined as having a positive or negative CTC status, respectively. The QPCR measurement and QDA data analysis in this way offers a simple and objective estimate of tumour cell presence in a given sample. Survival was illustrated by Kaplan–Meier plots and compared between groups by the log rank test. Clinicopathological factors known to be associated with prognosis (age ⩽45 years vs >45 years), tumour size (T2 and T3 vs T1), lymph node involvement (yes vs no), both following TNM 6 classification according to Union Internationale Contre le Cancer criteria (Sobin and Wittekind, 2002), histological grade (3 vs 1 or 2), oestrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR) hormone receptor (both negative vs either or both positive) and HER2 (positive=3+ in immunohistochemistry or in fluorescent in situ hybridisation vs negative) were tested in univariate analysis to calculate hazard ratios (HRs), their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P-value. Variables that were found to be significant or with the HR >2.0 or <0.5 in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate Cox regression model to identify those with independent prognostic information and furthermore to calculate HRs and their 95% CIs.

Results

Study inclusion and patient characteristics

A total of 82 women with early-stage breast cancer were included and a peripheral blood sample was obtained before surgery and before initiating adjuvant therapy. The clinical characteristics are described in Table 2. The median age was 56 years (range: 34–86 years), 70 (85%) were >45 years, 12 (15%) had stage III disease at diagnosis, 20 (24%) had tumours >2 cm, 22 (27%) had infiltrated axillary lymph nodes, 18 (22%) had tumours with histological grade 3, 9 (11%) had tumours that were ER and PR negative and 28 (22%) had tumours that were HER2 positive. In total, 68 (83%) of the patients received any type of adjuvant therapy and 14 (17%) received trastuzumab therapy. The median time from diagnosis to blood collection was 14 days (range: 0.0–61 days) and the median follow-up time from sampling to ‘relapse of disease’ or ‘last follow-up’ was 51 months (range: 17–60). The median follow-up time for patients who did not experience an event was 51 months (range: 40–60).

Circulating tumour cell detection in patient groups

In this prospective study, 16 (20%) of the 82 primary breast cancer patients who were included had a positive QDA score (Figure 1). The majority of patients with a QDA-positive score (12 out of 16; 75%) had a blood sample that was positive for the EGP marker gene and at least one other marker gene (5 out of 16, 31% was EGP and p1B positive; 4 out of 16, 25% was EGP and CK19 positive; and 3 out of 16, 19% was EGP, p1B and CK19 positive). The four other QDA-positive patients (4 out of 16, 25%) had a blood sample that was EGP negative but positive for both p1B and MmGl. The sensitivity and specificity of our test was 20% (95% CI: 12–30) and 100% (95% CI: 92–100), respectively. The distribution of patient and primary tumour tissue characteristics were not significantly different between the CTC-positive and CTC-negative patients (Table 2). The median age at diagnosis was 55 (range: 36–84) and 57 (range: 34–86) for the CTC-positive and CTC-negative patients, respectively. In addition to this, a female healthy volunteer control group (n=45, none positive) and advanced breast cancer patients group (n=16; 13 (81%) positive) were tested (Figure 1). The QDA values among advanced breast cancer patients were higher compared with early breast cancer patients as well as with healthy controls (Mann–Whitney U-test: both P<0.001), although there was no significant difference between early-stage patients and healthy controls (P=0.123). Median QDA values (range) were −1.16 (−9.78 to 0.00), −1.16 (−6.25 to 1.99) and 2.39 (−1.16 to 3.69) for the healthy controls group, early-stage breast cancer patients and advanced breast cancer patients, respectively. For further analysis, patients with a zero or negative QDA were considered ‘CTC-negative’ and patients with a positive QDA were considered ‘CTC-positive’.

Quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) values incorporating the expression of the four marker genes CK19, p1B, EGP and MmGl measured in the peripheral blood of healthy controls (n=45; open circles), early-stage breast cancer (BC) patients (n=82; triangles) and advanced BC patients (n=16; closed circles). The median expression levels for the QDA are indicated by a horizontal line (healthy controls=−1.16, early-stage BC patients=−1.16, advanced breast cancer patients=2.39).

CTC status at the time of diagnosis and clinical outcome

During follow-up period of the early breast cancer patients, 12 patients (14%) experienced clinical relapse: 6 of whom were CTC positive (38% of all CTC-positive patients), and 6 of whom were CTC negative (9% of all CTC-negative patients; Fisher's exact test: P=0.010; Table 3). One CTC-positive patient had a local relapse, followed by distant metastasis 1 month later. The other 11 patients had distant metastases in pleura, liver, brain, bone or in multiple sites.

Despite the relatively short follow-up period of this prospective study, CTC status at the time of diagnosis as determined by our assay was a significant predictor of relapse-free survival, with a hazard ratio of 4.72 (95% CI: 1.52–14.66, P=0.003; Figure 2 and Table 4). Importantly, multivariate analysis demonstrated that CTC status at the time of diagnosis was a significant and independent predictor of relapse-free survival (multivariate Cox regression, multivariate hazard ratio=5.13, P=0.006, 95% CI: 1.62–16.31; Table 5). The 4-year relapse-free survival rates were 92 and 69% for CTC-negative and CTC-positive patients, respectively (Figure 2).

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for relapse-free survival of early-stage breast cancer patients (n=82) who were CTC negative (n=66) or positive (n=16) at diagnosis. CTC-positive patients had a significantly poorer relapse-free survival than CTC-negative patients (univariate hazard ratio=4.72; 95% CI: 1.52–14.66; log rank test P=0.003). The number of patients at risk at each time point (months) are indicated for the CTC-negative (black) and CTC-positive (grey) groups. Abbreviations: CTC-positive or CTC-negative=positive or negative circulating tumour cell status according to quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) score; FU=follow-up.

During the follow-up period, death occurred in total in eight patients, of which five were breast cancer related and three were by other causes (Table 3). One death occurred in the CTC-positive group and this was a breast cancer-related death (6% of all CTC-positive patients) with pleural metastases. In the CTC-negative group, four breast cancer-related deaths and three deaths by other causes occurred (6% and 5%, respectively, of all CTC-negative patients). The patients with breast cancer-related death had pleural, skin, bone and liver metastases. There was no significant difference in overall- and breast cancer-related survival between the CTC-positive and CTC-negative group (Fisher's exact test and Pearson's χ2-test: P=1.000 and P=0.686, respectively; Table 3). CTC positivity was not associated with breast cancer-related or overall survival with a hazard ratio of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.11–9.09, P=0.989) and 0.57 (95% CI: 0.07–4.63, P=0.594), respectively. The 4-year overall survival rates were 91 and 94% for CTC-negative and CTC-positive patients, respectively.

Additional analyses: effect of frozen storage and the value of repeated sampling after therapy

We assessed the effect of frozen storage in eight early-stage and one advanced breast cancer patients and five healthy controls. All samples had a concordant CTC status in both the fresh and stored sample.

We also used the assay in peripheral blood samples of a subset of patients who were CTC negative at diagnosis and had remained disease free. Of the 45 women who participated, 40 women tested CTC negative and 5 women (5 out of 45 (11%)) tested CTC positive, currently without experiencing a diagnosed relapse of disease. During follow-up (median time from second blood collection to last follow-up: 6.2 months; range: 0.0–13) no relapses or deaths occurred.

Discussion

An optimised CTC assay was used to estimate circulating tumour cell load in prospectively collected peripheral blood samples of 82 early-stage and 16 advanced breast cancer patients and 45 healthy female controls. In early-stage breast cancer patients, the sensitivity of our assay was 20%. Based on the data from several published studies with early-stage breast cancer patients (Pierga et al, 2008; Rack et al, 2008; Daskalaki et al, 2009; Xenidis et al, 2009; Krishnamurthy et al, 2010; Riethdorf et al, 2010) the assay's sensitivity was found to be comparable with other assays with high specificity, except for Daskalaki et al (2009) who found a higher sensitivity of 52.4% with a specificity of 97.8% in a study that had only included stage I and II breast cancer patients. The CellSearch system (Veridex, Warren, NJ, USA) is one of the most used and validated commercial CTC detection platforms currently available (Allard et al, 2004; Balic et al, 2005; Cristofanilli et al, 2007; Riethdorf et al, 2007; Krishnamurthy et al, 2010). This method was used in the recent GeparQuattro clinical trial where CTCs were prospectively monitored in neo-adjuvant therapy. Here, at baseline a sensitivity of 21.6% was found for CTC positivity, using a cutoff of ⩾1 CTC/7.5 ml peripheral blood (Riethdorf et al, 2010). While generally demonstrating a similar sensitivity and specificity to the CellSearch system, our assay offers several other advantages: first, our assay is objective, as an algorithm generates a single score automatically for determining CTC positivity based on tumour marker gene expression levels detected by QPCR. This is in contrast to the CellSearch system, in which images of cells are determined to be CTCs by software and need to be manually confirmed by an operator. This step can introduce subjectivity in scoring, which is significant when as few as one or two cells in a sample are sufficient to class the patient as ‘CTC-positive’. Recently, Kraan et al (2011) observed that image interpretation was the main contributor to between-laboratory variation. In addition, our assay is considerably less expensive, costing less than US$25 per sample, compared with approximately US$600 per sample for the CellSearch system (Kaiser, 2010). Finally, there already exists an equipment for the automation of the enrichment, cDNA preparation and QPCR steps in our assay, and hence it could potentially require little manual work or technical knowledge. Although this is a preliminary study and further validation involving additional patients would be required to confirm that an automated system could provide equivalent prognostic data, there is a potential for the use of such system in a clinical setting.

The threshold for QDA positivity was set at the highest QDA value in the healthy controls group, resulting in 100% specificity, as previously described (Bosma et al, 2002; Weigelt et al, 2003). Although our assay's sensitivity could have been augmented by lowering the threshold, priority was given to avoid false positives.

In total, 81% of the advanced patients assayed were CTC positive vs 0% of the healthy controls (Figure 1). We hypothesised that enriching a sample for tumour cells before assessing tumour marker gene expression would be beneficial for assay sensitivity, and this appears to be the case. We had previously demonstrated that when tumour cell enrichment was not performed, 30% of advanced patients assayed from a similarly selected patient group had a positive QDA score indicating CTC positivity vs 0% of healthy controls (Weigelt et al, 2003). We also had previously shown that using a positive enrichment strategy for cells expressing both EpCam and ErbB2 antigens resulted in the detection of higher levels of tumour marker gene expression than enriching for cells expressing just one of the antigens (Molloy et al, 2008). Also, the multimarker gene expression panel used has obvious benefits over the use of a single marker for the detection of tumour cells. Finally, the use of the quadratic discriminant score function is not prone to subjectivity in scoring or inaccuracies in quantitation as immunohistochemical staining or densitometry of an electrophoresed nucleic acid band can be.

Our platform also has limitations using immunomagnetic bead selection with antibodies directed at EpCam and ErbB2. This may very well also have caused a bias by not selecting any potential EpCam and ErbB2 non- or low-expressing cells. It is believed that CTCs may lose EpCam in order to intravasate and to reach circulation, in a process called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Bonnomet et al, 2010). Indeed, Sieuwerts et al (2009) showed that a subtype of breast cancer cells is not detected in the EpCam-based CellSearch assay. Consistent with this hypothesis, in the present study, blood samples of 17 early-stage EGP-negative patients were found positive for one or more of the other three marker genes (data not shown). These studies and our data confirm that indeed there may be phenotypic differences between CTCs.

Our previous study using non-tumour cell-enriched blood samples from advanced patients demonstrated that CTC status was an independent predictor of both progression-free and overall survival (Weigelt et al, 2003). The CTC positivity as determined by our assay was a significant predictor of relapse-free survival in the primary breast cancer patient cohort (multivariate HR=5.13, P=0.006, 95% CI: 1.62–16.31; Table 5). Importantly, multivariate analyses demonstrated that CTC status provided significant prognostic information that was independent of other commonly used clinical variables, including age at diagnosis, lymph node status, histological grade, hormone receptor status and HER2 status (Tables 4 and 5). Tumour size, which is known for its prognostic value, did not reach statistical significance in our analysis. In contrast to predicting for relapse, CTC positivity was not a predictor for breast cancer-related or overall survival. Others have demonstrated a significantly reduced survival for CTC-positive early-stage breast cancer patients (Rack et al, 2008; Daskalaki et al, 2009; Xenidis et al, 2009). The observation that CTC positivity did not predict for survival in the present study may be because of the combination of a follow-up time that was relatively short for the observation of deaths and the occurrence of a limited number of events, being eight deaths in total.

Additional exploratory analyses of our assay on the effect of frozen storage, which found concordant results in all samples, indicated the possibility to store freshly collected samples for a longer period and to process them later. If confirmed on a larger scale, this method would greatly facilitate sample collection and would present another advantage to other methods described earlier (Daskalaki et al, 2009), including the CellSearch system in which samples are required to be processed within 72 h (Riethdorf et al, 2007). The analysis on the value of repeated sampling after therapy did not show relevance during the relatively short follow-up, and the prospective value of this second sampling will be studied in the future in ongoing follow-up.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a sensitive and specific platform for the detection of circulating tumour cells in both advanced and early-stage breast cancer patients. In this study with early-stage breast cancer patients, we found that our assay was prognostic for relapse-free survival. Further work will be required in prospective trials to fully determine whether our assay can be used to improve disease outcome in patients who are CTC positive.

Change history

29 March 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AG, Uhr JW, Terstappen LW (2004) Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res 10: 6897–6904

Balic M, Dandachi N, Hofmann G, Samonigg H, Loibner H, Obwaller A, van der Kooi A, Tibbe AG, Doyle GV, Terstappen LW, Bauernhofer T (2005) Comparison of two methods for enumerating circulating tumor cells in carcinoma patients. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 68: 25–30

Bieche I, Laurendeau I, Tozlu S, Olivi M, Vidaud D, Lidereau R, Vidaud M (1999) Quantitation of MYC gene expression in sporadic breast tumors with a real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay. Cancer Res 59: 2759–2765

Bonnomet A, Brysse A, Tachsidis A, Waltham M, Thompson EW, Polette M, Gilles C (2010) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions and circulating tumor cells. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 15: 261–273

Bosma AJ, Weigelt B, Lambrechts AC, Verhagen OJ, Pruntel R, Hart AA, Rodenhuis S, van’t Veer LJ (2002) Detection of circulating breast tumor cells by differential expression of marker genes. Clin Cancer Res 8: 1871–1877

Braun S, Pantel K, Muller P, Janni W, Hepp F, Kentenich CR, Gastroph S, Wischnik A, Dimpfl T, Kindermann G, Riethmuller G, Schlimok G (2000) Cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow and survival of patients with stage I, II, or III breast cancer. N Engl J Med 342: 525–533

Cristofanilli M, Broglio KR, Guarneri V, Jackson S, Fritsche HA, Islam R, Dawood S, Reuben JM, Kau SW, Lara JM, Krishnamurthy S, Ueno NT, Hortobagyi GN, Valero V (2007) Circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: biologic staging beyond tumor burden. Clin Breast Cancer 7: 471–479

Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ, Terstappen LW, Hayes DF (2004) Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351: 781–791

Cristofanilli M, Hayes DF, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Matera J, Allard WJ, Miller MC, Fritsche HA, Hortobagyi GN, Terstappen LW (2005) Circulating tumor cells: a novel prognostic factor for newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 1420–1430

Daskalaki A, Agelaki S, Perraki M, Apostolaki S, Xenidis N, Stathopoulos E, Kontopodis E, Hatzidaki D, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V (2009) Detection of cytokeratin-19 mRNA-positive cells in the peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with operable breast cancer. Br J Cancer 101: 589–597

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong JH, Wolmark N (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347: 1233–1241

Fitzgibbons PL, Page DL, Weaver D, Thor AD, Allred DC, Clark GM, Ruby SG, O’Malley F, Simpson JF, Connolly JL, Hayes DF, Edge SB, Lichter A, Schnitt SJ (2000) Prognostic factors in breast cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124: 966–978

Hand DJ (1992) Statistical methods in diagnosis. Stat Methods Med Res 1: 49–67

Kaiser J (2010) Medicine. Cancer's circulation problem. Science 327: 1072–1074

Kraan J, Sleijfer S, Strijbos MH, Ignatiadis M, Peeters D, Pierga JY, Farace F, Riethdorf S, Fehm T, Zorzino L, Tibbe AG, Maestro M, Gisbert-Criado R, Denton G, de Bono JS, Dive C, Foekens JA, Gratama JW (2011) External quality assurance of circulating tumor cell enumeration using the CellSearch((R)) system: A feasibility study. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 80: 112–118

Krishnamurthy S, Cristofanilli M, Singh B, Reuben J, Gao H, Cohen EN, Andreopoulou E, Hall CS, Lodhi A, Jackson S, Lucci A (2010) Detection of minimal residual disease in blood and bone marrow in early stage breast cancer. Cancer 116: 3330–3337

Levi F, Bosetti C, Lucchini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C (2005) Monitoring the decrease in breast cancer mortality in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev 14: 497–502

Mansi JL, Gogas H, Bliss JM, Gazet JC, Berger U, Coombes RC (1999) Outcome of primary-breast-cancer patients with micrometastases: a long-term follow-up study. Lancet 354: 197–202

McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM (2006) REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Breast Cancer Res Treat 100: 229–235

Molloy TJ, Bosma AJ, van’t Veer LJ (2008) Towards an optimized platform for the detection, enrichment, and semi-quantitation circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 112: 297–307

Muller V, Pantel K (2009) HER2 as marker for the detection of circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 117: 535–537

Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, Baehner FL, Walker MG, Watson D, Park T, Hiller W, Fisher ER, Wickerham DL, Bryant J, Wolmark N (2004) A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351: 2817–2826

Pantel K, Cote RJ, Fodstad O (1999) Detection and clinical importance of micrometastatic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 1113–1124

Pierga JY, Bidard FC, Mathiot C, Brain E, Delaloge S, Giachetti S, de Cremoux P, Salmon R, Vincent-Salomon A, Marty M (2008) Circulating tumor cell detection predicts early metastatic relapse after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in large operable and locally advanced breast cancer in a phase II randomized trial. Clin Cancer Res 14: 7004–7010

Pinder SE, Ellis IO, Galea M, O’Rouke S, Blamey RW, Elston CW (1994) Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. III. Vascular invasion: relationship with recurrence and survival in a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology 24: 41–47

Rack BK, Schindlbeck C, Schneeweiss A, Hilfrich J, Lorenz R, Beckmann MW, Pantel K, Lichtenegger W, Sommer HL, Janni WJ (2008) Prognostic relevance of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in peripheral blood of breast cancer patients before and after adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 26(15S): 851–858

Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Muller V, Rau T, Schindlbeck C, Rack B, Janni W, Coith C, Beck K, Janicke F, Jackson S, Gornet T, Cristofanilli M, Pantel K (2007) Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a validation study of the CellSearch system. Clin Cancer Res 13: 920–928

Riethdorf S, Muller V, Zhang L, Rau T, Loibl S, Komor M, Roller M, Huober J, Fehm T, Schrader I, Hilfrich J, Holms F, Tesch H, Eidtmann H, Untch M, von Minckwitz G, Pantel K (2010) Detection and HER2 expression of circulating tumor cells: prospective monitoring in breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant GeparQuattro trial. Clin Cancer Res 16: 2634–2645

Rosen PP, Groshen S, Saigo PE, Kinne DW, Hellman S (1989) Pathological prognostic factors in stage I (T1N0M0) and stage II (T1N1M0) breast carcinoma: a study of 644 patients with median follow-up of 18 years. J Clin Oncol 7: 1239–1251

Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, van der Spoel P, Elstrodt F, Schutte M, Martens JW, Gratama JW, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA (2009) Anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies and the detection of circulating normal-like breast tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 101: 61–66

Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch (eds) (2002) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 6th edn. Wiley: Hoboken, NJ

van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van’t Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, Schreiber GJ, Peterse JL, Roberts C, Marton MJ, Parrish M, Atsma D, Witteveen A, Glas A, Delahaye L, van der Velde T, Bartelink H, Rodenhuis S, Rutgers ET, Friend SH, Bernards R (2002) A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347: 1999–2009

Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Yang F, Talantov D, Timmermans M, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Yu J, Jatkoe T, Berns EM, Atkins D, Foekens JA (2005) Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet 365: 671–679

Weigelt B, Bosma AJ, Hart AA, Rodenhuis S, van’t Veer LJ (2003) Marker genes for circulating tumour cells predict survival in metastasized breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer 88: 1091–1094

Weigelt B, Verduijn P, Bosma AJ, Rutgers EJ, Peterse HL, van’t Veer LJ (2004) Detection of metastases in sentinel lymph nodes of breast cancer patients by multiple mRNA markers. Br J Cancer 90: 1531–1537

Xenidis N, Ignatiadis M, Apostolaki S, Perraki M, Kalbakis K, Agelaki S, Stathopoulos EN, Chlouverakis G, Lianidou E, Kakolyris S, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D (2009) Cytokeratin-19 mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27: 2177–2184

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr S Rodenhuis for providing clinical data and patient samples. This work was supported by the Sixth Framework Program of the European Commission as part of the international DISMAL collaboration for research into disseminated epithelial malignancies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Molloy, T., Devriese, L., Helgason, H. et al. A multimarker QPCR-based platform for the detection of circulating tumour cells in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Br J Cancer 104, 1913–1919 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.164

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.164

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

miR-10a as a therapeutic target and predictive biomarker for MDM2 inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia

Leukemia (2021)

-

Nerve growth factor: role in growth, differentiation and controlling cancer cell development

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2016)

-

The long noncoding RNA SPRY4-IT1 increases the proliferation of human breast cancer cells by upregulating ZNF703 expression

Molecular Cancer (2015)

-

Single cell analysis of cancer cells using an improved RT-MLPA method has potential for cancer diagnosis and monitoring

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer and its association with tumor clinicopathological characteristics: a meta-analysis

Medical Oncology (2014)