Key Points

-

Refreshes knowledge and reviews the causes of microstomia and mandibular hypomobility.

-

Introduces and reviews available treatment options.

-

Outlines recommendations when undertaking dental treatment for patients with reduced oral aperture and mandibular hypomobility.

Abstract

Reduced oral aperture and mandibular mobility/trismus are relatively common conditions that can be encountered in patients attending general dental practice, community dental practice and district general or dental teaching hospitals. All dental specialties may see patients with these conditions, and regardless of which environment or specialty, both patient and clinician may experience significant problems. The purpose of this opinion-based paper is to identify and review the causes of such conditions, to review the development of problems encountered for patients and clinicians, and to identify options to treat or manage the conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Aetiology

Limited access to the oral cavity can present significant problems for patients, their carers, and dental and other professionals. This may arise from a limited oral aperture – microstomia, or mandibular hypomobility/trismus. A variety of causes can be identified for both these conditions and while microstomia is essentially a chronic condition, mandibular hypomobility may be either acute or chronic.

Microstomia

Microstomia is a chronic reduction in the dimensions of the oral aperture and although it is not classified by any particular size criteria, it is defined by its effects on function or appearance.1 It is often associated with systemic conditions or autoimmune diseases affecting the connective tissues (such as scleroderma), and may also be encountered in conjunction with a number of oro-facial syndromes. Furthermore, it may arise as a result of post-surgical scarring following peri-oral procedures, or following trauma, particularly electrical or chemical burn injuries.2

Patients with scleroderma develop tightening of the skin with sclerosis of the dermis; additionally, fibrotic changes of the orbicularis oris muscle may be present. Following burn injuries, the reduced oral aperture may be the result of initial coagulative necrosis with inflammation of adjacent vital tissues. Over several weeks, the necrotic cells are removed by fragmentation and phagocytosis of the cellular debris and by the action of proteolytic lysosomal enzymes. Subsequently, fibroblast formation and collagen deposition occur, along with scar tissue formation and contraction.

Microstomia following tumour resection has become much less common as a result of modern reconstructive techniques. Pedicle, rotational, or free-flap techniques that recruit additional tissue to compensate for an area of lip that has been resected are helpful in maintaining the oral aperture (Figs 1, 2, 3).

Mandibular hypomobility

Acute mandibular hypomobility is most often related to mandibular/facial trauma (Fig. 4) or iatrogenic causes such as third molar extraction or intramuscular haematoma (eg from intramuscular administration of local anaesthetic solution during an inferior dental block).1 In most cases reduced mandibular opening arising from iatrogenic causes will be self-limiting and therefore of limited consequence with respect to long-term dental/oral management. Careful local anaesthetic delivery is the most effective way to avoid iatrogenically induced mandibular hypomobility. For cases where severe trauma has been the aetiologic factor, chronic mandibular hypomobility is more likely to be the resultant outcome. This may be further compounded by reduction in size of the oral aperture (4, 5, 6).

Chronic mandibular hypomobility may arise from a range of causes, including temporomandibular joint pathology2 (in most cases self-limiting or of relatively short duration), direct trauma, surgery (Figs 7 and 8), or as an effect of local radiation treatment for neoplastic disease. It may arise from problems distant to the joint or muscles, including local infection, neoplasia, and other systemic diseases (eg connective tissue disorders such as lupus and scleroderma, or central nervous system disorders).2,3

Chronic reduction in oral opening is relatively uncommon in the general population but may be seen in a significant proportion of patients who have undergone treatment for an oral cancer by surgery, radiotherapy, chemoradiotherapy or combinations of these (Figs 9 and 10). The prevalence of post-radiotherapy mandibular hypomobility has been reported to vary between 5% and 38%.4,5 This wide prevalence range may be accounted for by the variation in study methods. The variable incidence of mandibular hypomobility within this patient cohort appears to depend on a number of factors. These include: the location of the tumour, the nature and extent of surgery, the field of tissue irradiated, use of combined surgery and adjunctive radiotherapy, and the level of mobilisation encouraged and performed by the patient in the period immediately following treatment. Similarly, individual patient variation may have an effect, including advanced age, obesity, reduced tissue vascularity and other co-morbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes and connective tissue diseases.

Development

The mechanisms by which mandibular hypomobility develops, and the factors which determine speed of onset, severity, and extent, are poorly understood. It is generally viewed to be the result of fibrosis and scarring of affected tissues, particularly muscles, leading to a loss of flexibility and extension. As a result of surgery and/or radiotherapy there can be initial limitation of movement. Muscle atrophy can then ensue if there has been no muscle use for as little as three days. In a similar manner, loss of temporomandibular joint mobility can rapidly result in changes to both articular cartilage and synovial fluid. Mandibular hypomobility may progress gradually during the recovery period, and result in secondary and irreversible changes in the joint and muscle structures.

If hypomobility develops following radiotherapy treatment it may be described as a radiation-induced fibroatrophic process and is regarded as a late consequence of high dose radiotherapy; it is often regarded as irreversible. Its development is thought to progress in three phases: an initial non-specific inflammatory phase, a fibrotic cellular phase and a matrix densification and remodelling phase.6

Implications

Patients affected by microstomia or mandibular hypomobility may have great problems when eating. Restriction in jaw movement and reduced chewing efficiency can result in an almost inevitable detrimental modification in diet content and consistency. Significant weight loss may result in patients who are recovering from cancer treatment, at a time when they most require adequate nutrition to aid recovery. Furthermore, with mandibular hypomobility, swallowing and airway clearance can be affected, leading to poor management of food and a risk of pulmonary aspiration of residual food bolus, which remains after the main swallow.

There can also be a significant impact on oral and dental health. Restricted oral access, in combination with its consequent dietary alteration, can compromise oral hygiene and patients can be more susceptible to developing caries or periodontal disease, especially if they are suffering with hyposalivation (another common side effect of craniofacial irradiation). Restricted opening may even prevent access by the dental professional for treatment of the dentition. For edentulous patients, normal impression techniques may not be possible and while the lack of natural teeth may allow a greater degree of interocclusal clearance, there may be inadequate vertical dimension for appropriate denture construction.

Treatment

It is of great importance that the development of mandibular hypomobility is prevented wherever possible. Encouraging the patient to maintain joint and muscle mobilisation throughout treatment and immediately after any surgical intervention is the best preventative measure. Passive motion rather than static stretching, performed regularly throughout the day, is the most appropriate way of minimising hypomobility.7

When mandibular hypomobility is anticipated then a record of inter-incisal opening before its onset may help gauge the effect of any treatment modality aimed at improving the situation. Regular measurements throughout treatment could alert the patient and/or clinician to the onset of hypomobility, which may develop some months after the initiating factor such as radiotherapy. There can be a wide variation in the normal range of opening; 35 to 60 mm taking account of any positive or negative overbite.8 However, it is likely that there is variation amongst patients in the level of restricted mandibular opening that causes functional problems. To overcome this it has been suggested that subjective assessment may be more useful.7

A recent systematic review of mandibular hypomobility in head and neck oncology described the effects of therapeutic interventions as being scarcely investigated.7 Although many of the interventions described have some rationale, there is little, if any, high quality evidence to support them. Treatment therefore tends to be pragmatic and empirical, and the chosen modality will be dependent on the cause of the hypomobility. What follows is a brief resumé of treatment modalities for mandibular hypomobility.

Physical therapies

The objective of physical therapies is to remove oedema, soften and stretch fibrous tissue, increase range of joint motion, restore circulatory efficiency, increase muscular strength and retain muscular dexterity.9

Thermal therapy

It has been suggested that management of mandibular hypomobility following inferior alveolar nerve block injection should include application of heated moist towels for 15-20 minutes every hour.1 Alternating heat and cold in combination with electrotherapy have also been advocated for muscle spasm.10

Mandibular opening devices and simple exercises

Numerous 'trismus appliances' have been described.9 Externally activated appliances use some form of mechanical means to actively open the mandible, and include: threaded tapered screws, fingers or tongue spatulas. An alternative unconventional approach may include the suspension of a free weight.11 Dynamic bite openers aim to depress the mandible through the use of springs or elastic bands, and the TheraBite Jaw Motion Rehabilitation System™ (Atos Medical AB, Sweden) uses repetitive, passive stretching. This system showed a significantly increased mouth opening in the short term versus use of tongue depressors or unassisted exercises in post-irradiated patients.12

Internally activated appliances and unassisted exercises rely on the depressor muscles to stretch the mandibular elevator muscles. Unassisted home exercises and devices such as stacked tongue depressors and a tapered cylinder may help monitor and sustain mandibular opening once achieved.3,9

Microstomia orthoses

A variety of appliances have been described for prevention or stretching of scar contractures that occur as a complication of facial burns, trauma, systemic sclerosis or reconstructive surgery involving the orbicularis oris muscle.13

Electrotherapy

Impedance-controlled micro-current is used in the treatment of chronic pain and scar tissue. This modality was investigated in 26 patients with radiation induced fibrosis affecting the cervical musculature.14 As well as sustained improvements in range of cervical movement, ten out of 16 patients who also had complaints of mandibular hypomobility reported improvement in oral opening. Measurements on all 26 patients showed that 21 had improved oral opening, which was sustained in seven of the 16 patients who had symptomatic mandibular hypomobility. However, the study had no control group.

Drugs

Regional local anaesthesia may alleviate muscle spasm; diazepam has also been advocated to reduce muscle spasm. Antibiotics may be needed if abscess is the cause of muscle spasm.1

In a study of 16 post-radiation patients, pentoxifylline (a drug which down-regulates mediators of fibrogenic reactions after radiation) appeared to exert a modest therapeutic effect on radiation-induced limitation of mandibular movement.15

Botulinium toxin has also been used in patients with post-radiation muscle spasm and myokymia.16

Other treatments

Electron therapy and hyperbaric oxygen was used to treat post-surgical and radiation sequelae in 16 patients who were followed up for three years. Although healing and quality of soft tissues improved there was no improvement in oral opening.17

Dental implications and management

Reduced oral access and mandibular hypomobility that is resistant to treatment can result in significant dental/oral implications. Procedures such as personal oral hygiene, dental examinations, and subsequently all dental treatment required may be both painful and dangerous for the patient, and difficult or impossible for the operator to undertake. It is therefore of paramount importance to establish effective preventative regimes in such cases. The clinical management of the problems associated with providing dental treatment for these patients has been reported most frequently by way of case reports.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32

Dental examination

For patients with head and neck cancer, the possibility of mandibular hypomobility arising as a result of treatment must be anticipated. A pre-treatment dental examination involving a full oral/dental/prosthodontic assessment should be undertaken as early as possible, and the effect of the surgery and/or radiotherapy anticipated. This assessment should be carried out by an appropriately trained dental specialist – in the UK a consultant in restorative dentistry with a special interest in oral oncology is the appropriate person to manage and co-ordinate the patient's care.33

At the time of presentation many oral cancer patients have frequently neglected their dental care.34 It is however important that oral disease be eliminated, and preventative regimes established, prior to the onset of further complications such as mandibular hypomobility, reduced oral aperture and hyposalivation. Whilst at one time the extraction of all teeth before irradiation was recommended,35 this is no longer accepted practice and only teeth with active infection or questionable prognosis should be extracted.36,37

Care should be taken when carrying out an examination for a head and neck cancer patient to ensure that the patient is positioned comfortably enough to tolerate the procedure, as distress caused at this stage can generate anxiety and limited co-operation for future treatment. An understanding of what the patient has gone through and acknowledgement of their apprehension and concerns about examination and treatment is essential.

It is important to ascertain the maximum mouth opening the patient has prior to the examination; the patient then understands the dentist is aware of the immediate complicating factor. Patients can often open with contracted/tense lips, and advice on relaxed opening can avoid fighting against contracted obicularis oris, mentalis and buccinator muscles. Forward planning in showing how a patient can partially open with a left or right excursion can also facilitate access to buccal aspects of molar teeth. Opening can be further limited by hyposalivation, where the clinically dry mucosa can be hard and uncomfortable to retract. Rinsing with water or the use of artificial saliva replacements can be beneficial. Coating of the reverse side of mirrors with aqueous based lubricants and the lips with a petroleum-based lubricant can moisten and facilitate retraction and vision.

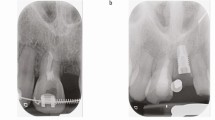

If a patient has not been seen and assessed before radiotherapy or surgical treatment, there may already be reduced mandibular opening, which will impact on the management of dental disease. Moderate restriction will pose difficulty in examination and treatment of all teeth. Severely limited opening may make examination of anterior teeth difficult, with only access to labial aspects. No access for examination will be possible to the palatal and lingual aspects of all the teeth and restorative treatment would probably be impossible (Figs 9 and 10).

Where restriction makes orthodox intra-oral examination impossible, then a radiographic examination technique may be used for the primary examination to aid diagnosis. For these cases, bitewing radiographs and dental panoramic tomograms (DPT) are usually possible and enable occlusal and proximal lesion detection. The DPT is usually relied on for assessment of peri-apical status, as long-cone peri-apical views will often be awkward or impossible to obtain.

Restorative treatment planning

The early diagnosis of caries and realistic treatment planning are essential when managing patients with reduced oral aperture or hypomobility. Following clinical and radiographic examination decisions have to be made; the fate of teeth with poor prognosis can be easy to decide; however, teeth with dubious prognosis can be somewhat more complicated. If the teeth are completely inaccessible, then arrangements need to be made for their early removal. Occasionally the restoration of a distal surface of a tooth can be facilitated by the temporary retention of the adjacent tooth as it can provide support for the restoration or for the matrix band during condensation. Conversely, the restoration of the mesial surface of a tooth can be facilitated by the loss of a more anterior tooth, if the ultimate removal of the latter is intended.

Following an initial examination, with experience, it may be possible to gauge a patients' future tolerance to treatment. However, for the majority of occasions it may be more advisable to attempt a simple line of treatment initially, and to gauge their response accordingly. This will facilitate the decision-making process for teeth with dubious prognosis, or prior to embarking on more complex periodontal, conservative or prosthodontic treatment.

Prevention, self-care and oral hygiene

Patient dexterity, motivation, and compliance can often be the limiting factors in establishing an effective preventative regime for patients with reduced access.38 For many patients adapting a powered tooth brushing technique with a small-headed design, or the use of a small-headed manual brush, should be sufficient to enable effective cleaning of the buccal and labial aspects of all teeth even in the presence of severe hypomobility. The lingual/palatal and occlusal aspects of teeth in the presence of severe hypomobility can prove more difficult to clean effectively. If, however, the patient has enough inter-incisal opening to allow for the handle of the brush to enter, there should be sufficient room to allow for cleaning. Absent opposing teeth may also facilitate this.

For a number of patients (especially head and neck cancer patients who often show poor general healthcare behaviour), effective plaque control is rarely achieved.38,39 For these patients, chlorhexidine mouthwash or gel may be considered, since it has been shown to be an effective method of plaque control and caries prevention.40,41,42 The cleaning of resection defects and mucosal surfaces maybe further facilitated with the use of intra-oral 'lollipop' sponges. The use of topical fluoride to reduce caries has also become standard practice in these patient groups. A suggested protocol involves the daily application of neutral sodium fluoride gel (5,000 ppm) in vacuform custom carriers,43 or the use of intraoral fluoride-releasing systems.44,45,46

Periodontal, conservative and endodontic treatment

Mandibular hypomobility will quite often limit the length of time treatment can be undertaken for a patient in a session; frequent breaks, moments of relaxation and the use of a mouth prop may reduce patient fatigue and prolong this a little. When undertaking periodontal or conservative treatment involving water coolant, adapting an appropriate suction technique is necessary. It may be possible to use a conventional wide-bore aspirator; however, use of smaller diameter or additional saliva ejectors or aspirators may be more appropriate. If the mandibular hypomobility is severe, it may not be possible to use suction at all, and treatment will need to be stopped and the patient instructed to expectorate/rinse.

Conservative treatment in the presence of mild to moderate mandibular hypomobility will probably allow for a conventional or miniature child-sized handpiece with suitable short-shank burs, with careful manipulation. In the presence of severe hypomobility, access to proximal and occlusal lesions in posterior teeth may be approached through the buccal aspect of the tooth, adapting a technique described by Howarth, caries removal and condensation of the restorative material can be achieved.19 In certain circumstances cavity preparation may be facilitated by use of a straight handpiece and straight bur.

Complex restorative treatment, such as crown and bridgework, in the presence of marked mandibular hypomobility may well be unrealistic and an impossible task (Fig. 11). However, resin-bonded bridgework with minimal or no preparation, and a simple impression technique, may be achievable to replace single isolated missing teeth in the anterior region, and avoid the need for a partial denture. Similarly, endodontic treatment will need to be prioritised for strategic/important teeth and may only be feasible for teeth in the anterior region. In such situations it may even be necessary to gain access to the pulp canal space via the labial aspect of the tooth. The use of an apex locator could confirm working lengths and avoid the need for further long-cone peri-apical radiographs. Similarly the use of rotary files of appropriate length to carry out the cleaning and shaping can allow for the safer instrumentation of the canals.

Figure 11 shows the difficulty in accessing a carious lesion affecting a lower anterior tooth. With a careful operating technique restoration is still achievable even in the presence of such restricted access.

Prosthodontic treatment

Limitation in opening can make it extremely difficult to gain access for prosthodontic treatment, and construction of a prosthesis may even be impossible. Recording of primary and major impressions, registration procedures, and even the relatively simple tasks of insertion and removal of the prosthesis may be problematic. It is, however, very much patient dependent and if denture construction and insertion can be tolerated, then this should be considered at the earliest opportunity, in order to facilitate the rehabilitation and self-dignity of the patient.

With mild reduction in opening, rotational paths of insertion and reduction in occlusal vertical dimension may be enough to facilitate conventional impression taking and continuation of a routine sequence of denture construction. However, problems develop when limitation of opening is more severe or where there are surgical resection defects that require an obturator of a larger dimension to restore the defect (Fig. 12). In these circumstances the use of sectional upper or lower impressions, for primary and master impressions, which may be recorded in two parts and relocated outside the mouth, can be helpful in obtaining a working cast.22,23,24,25,47 Alternatively a denture copying technique may avoid complex impression taking, and rely more on the general form of the existing prosthesis to act as a special tray.26,27 Where oral access is severely limited, alternative impression techniques have been described for fabricating obturators by using associated orbital defects,48 or using foam impression materials injected through the nostril into the nasal cavity.49 Following production of a working cast, a sectional two or three part design, or a flexible/collapsible/hinged prosthesis could be considered (Figs 12, 13, 14). These designs can be provided as either maxillary/mandibular appliances and will facilitate the insertion and removal of the appliance.28,29,30,31,50,51 In certain cases the degree of mouth opening can be so severe, it may have to be accepted that no treatment can be provided.

Implant treatment

The use of osseointegrated dental implants after surgical resection and/or radiotherapy treatment is a real opportunity to improve the quality of life for these patients.18,20,52However, reduced mouth opening of the conscious patient that prevents instruments from safely entering the mouth in order to insert and restore implants is clearly the critical factor in determining whether this line of treatment can be provided. Future maintenance of implant superstructures will understandably also be complicated due to the restriction.

Conclusions

Reduced oral aperture and mandibular opening are relatively common problems, which have a wide variety of causes. In some situations problems may be transient and self-limiting whilst for other patients, the situation is permanent and very troublesome for both patients and clinicians. The implications of the conditions are wide, and depend very much on the degree of restriction. Functional difficulties may include eating and speaking. Dental examination may be compromised and in severe cases the patient's self performed oral hygiene and dental treatment is impossible. Various strategies exist to attempt to prevent reduced oral aperture and reduced mandibular opening, and several useful techniques and manoeuvres have been documented to facilitate operative dentistry.

References

Dhanrajani P J O . Trismus: aetiology, differential diagnosis and treatment. Dent Update 2002; 29: 88–94.

Zarb G C G, Sessle B J, Mohl N D . Temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscle disorders. Munksgaard, 1994.

Vissink A, Burlage F R, Spijkervet F K L, Jansma J, Coppes R P . Prevention and treatment of the consequences of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003; 2003: 213–225.

Steelman R, Sokol J . Quantification of trismus following irradiation of the temporomandibular joint. Mo Dent J 1986; 66: 21–23.

Thomas F, Ozanne F, Mamelle G, Wibault P, Eschwege F . Radiotherapy alone for oropharangeal carcinomas: the role of fraction size (2 Gy vs 2.5 Gy) on local control and early and late complications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1988; 15: 1097–1102.

Delanien S, Lefaix J-L . The radiation-induced fibroatrophic process: therapeutic perspective via the antioxidant pathway. Radiother Oncol 2004; 73: 119–131.

Dijkstra P U, Kalk W W I, Roodenberg J L N . Trismus in head and neck oncology: a systematic review. Oral Oncol 2004; 40: 879–889.

Mezitis M R G, Zacharides N . The normal range of mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984; 47: 1028–1029.

Lund T D C J . Trismus appliances and indications for their use. Quintessence Int 1993; 24: 275–279.

Barrett N, Jacob R F, Kind G E . Physical therapy techniques in the treatment of the head and neck patient. J Prosthet Dent 1988; 59: 343–346.

Abdel-Galil K, Anand R, Pratt C, Oeppen B, Brennan P . Trismus: an unconventional approach to treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 2007; 45: 339–340.

Kaplan A J, Urken M L, Buchbinder D C R . Mobilization regimes for the prevention of jaw hypomobility in the radiated patient: a comparison of three techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 51: 863–867.

Conine T A, Carlow D L, Stevenson-Moore P . The Vancouver microstomia orthosis. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 61: 476–483.

Lennox A J, Schafer J P, Hatcher M, Beil J, Funder S J . Pilot study of impedancecontrolled microcurrent therapy for managing radiation-induced fibrosis in head-and-neck cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 54: 23–34.

Chua D T, Lo C, Yuen J, Foo Y C . A pilot study of pentoxifylline in the treatment of radiation-induced trismus. Am J Clin Oncol 2001; 24: 366–369.

Lou J S, Pleninger P, Kurlan R . Botulinum toxin A is effective in treating trismus associated with postradiation myokymia and muscle spasm. Mov Disord 1995; 10: 680–681.

King G E, Sheetz J, Jacob R F, Martin J W . Electroptherapy and hyperbaric oxygen: promising treatments for postradiation complications. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 62: 331–334.

Cheng A C, Wee A G, Shiu-Yin C, Tat-Keung L . Prosthodontic management of limited oral access after ablative tumor surgery: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 84: 269–273.

Howarth J H . Conservative procedures on patients with a limited oral opening. Br Dent J 1973; 135: 280–282.

Langer Y, Cardash H S, Tal H . Use of dental implants in the treatment of patients with scleroderma: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 68: 873–875.

Moghadam B K . Preliminary impression in patients with microstomia. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 67: 23–25.

Luebke R J . Sectional impression tray for patients with constricted oral opening. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 52: 135–137.

Cura C, Cotert H S, User A . Fabrication of a sectional impression tray and sectional complete denture fro a patient with microstomia and trismus:A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2003; 89: 540–543.

Dhanasomboon S, Kiatsiriroj K . Impression procedure for a progressive sclerosis patient: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 83: 279–282.

Barker P S, Brandt R L, Boyajian G . Impression procedure for patients with severely limited mouth opening. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 84: 241–244.

McMillan A S, Murray I D . Replacement of a maxillary obturator using a denture-copying technique: a case report. Quintessence Int 1995; 26: 703–706.

Heasman P A, Thomason J M, Robinson J G . The provision of prostheses for patients with severe limitation in opening of the mouth. Br Dent J 1994; 176: 171–174.

McCord J F, Tyson K W, Blair I S . A sectional complete denture for a patient with microstomia. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 61: 645–647.

Suzuki Y, Abe M, Hosoi T, Kurtz K S . Sectional collapsed denture for a partially edentulous patient with microstomia: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 84: 256–259.

Cheng A C, Wee A G, Morrison D, Maxymiw W G . Hinged mandibular removable complete denture for post-mandibulectomy patients. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82: 103–106.

Al-Hadi L A . A simplified technique for prosthetic treatment of microstomia in a patient with scleroderma: a case report. Quintessence Int 1994; 25: 531–533.

Wang R R . Sectional prosthesis for total maxillectomy patients: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 1997; 78: 241–244.

Otorhinolaryngologists BAO. Effective head and neck cancer management. London: Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2002.

Miller E C, Vergo T J, Feldman M I . Dental management of patients undergoing radiation therapy for cancer of the head and neck. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1981; 2: 350–356.

Del Regato J A . Dental lesions observed after roentgen therapy in cancer of the buccal cavit, pharynx and larynx. Am J Roentgenol 1939; 42: 404–410.

Thorn J J, Sand Hansen H, Speecht L, Bastholt L . Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: clinical characteristics and relation to the field of irradiation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000; 58: 1088–1093.

Jansma J, Vissink A, Spijkervet F K L, Panders AK et al. Protocol for the prevention and treatment of oral complications of head and neck radiotherapy. Cancer 1992; 70: 2171–2180.

Epstein J B, Van der Meij E H, Lunn R, Stevenson-Moore P . Effects of compliance with fluoride gel application on caries and caries risk in patients after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1996; 82: 268–275.

Lockhart P B, Clark J . Pretherapy dental status of patients with malignant conditions of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 77: 236–241.

Gjermo P . Chlorhexidine and related compounds. J Dent Res 1989; 68: 1602–1608.

Epstein J B, Loh R, Stevenson-Moore P, McBride B C, Spinelli J . Chlorhexidine rinse in prevention of dental caries in patients following radiation therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989; 68.

Epstein J B, McBride B C, Stevenson-Moore P, Merilees H, Spinelli J . The efficacy of chlorhexidine gel in reduction of Streptococcus mutans and lactobacillus species in patients treated with radiation therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991; 71: 172–178.

Dreizen S, Brown L R, Daly T E, Drane J B . Prevention of xerostomia-related dental caries in irradiated cancer patients. J Dent Res 1977; 56: 99–104.

Meyerowitz C, Watson G E . The efficacy of an intraoral flouride-releasing system in irradiated head and neck cancer patients: a preliminary study. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129: 1252–1259.

Mirth D B, Shern R J, Emilson C G . Clinical evaluation of an intraoral device for the controlled release of fluoride. J Am Dent Assoc 1982; 105: 791–797.

Corpron R E, Clark J W, Tsai A . Intraoral effects of a fluoride-releasing device on acid softened enamel. J Am Dent Assoc 1986; 113: 383–388.

Moghadam B K . Preliminary impression in patients with microstomia. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 67: 23–25.

Taylor T D, Fyler A, LaVelle W E . Alternative obturation for the maxillectomy patient with severely limited mandibular opening. J Prosthet Dent 1985; 53: 83–85.

Schmaman J, Carr L . A foam impression technique for maxillary defects. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 68: 342–344.

Wahle J J, Gardner L K, Fiebiger M . The mandibular swing-lock complete denture for patients with microstomia. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 68: 523–527.

Lauciello F R, Casey D M, Crowther D S . Flexible temporary obturators for patients with severely limited jaw opening. J Prosthet Dent 1983; 49: 523–526.

Marunick M T, Roumanas E D . Functional criteria for mandibular implant placement post resection and reconstruction for cancer. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82: 107–113.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garnett, M., Nohl, F. & Barclay, S. Management of patients with reduced oral aperture and mandibular hypomobility (trismus) and implications for operative dentistry. Br Dent J 204, 125–131 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.47

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.47

This article is cited by

-

Complete dentures: an update on clinical assessment and management: part 2

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

CANDLE SYNDROME: Orofacial manifestations and dental implications

Head & Face Medicine (2015)

-

Contemporary issues in the provision of restorative dentistry

British Dental Journal (2012)

-

Limited mouth opening after primary therapy of head and neck cancer

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (2010)