Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The understanding about why neonates die in rural areas in developing countries is limited. In the first year (1995 to 1996) of the field trial of home-based neonatal care in rural Gadchiroli, India, we prospectively observed a cohort of neonates in 39 villages. In Part I of this article, we presented the primary causes of death. The data were further analyzed:

-

1

To estimate the population attributable risk (PAR) of death for the main causes of neonatal mortality.

-

2

To evaluate the effect of a multiplicity of morbidities and to identify which morbidity combinations cause neonatal deaths.

-

3

To develop a hypothesis about how best to reduce neonatal mortality.

STUDY DESIGN:

We analyzed the observational data by logistic regression to estimate the PAR of death for six major morbidities. The effect of the number of morbidities per neonate on case fatality (CF) was estimated. Then we identified the main combinations of morbidities as the component causes leading to death. We estimated the excess deaths attributable to sepsis.

RESULTS:

This cohort included 763 neonates among whom 40 neonatal deaths occurred. Six major morbidities were associated with the following proportion of deaths: preterm, 62.5%; sepsis, 60%; intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), 27.5%; asphyxia, 25%; hypothermia, 22.5%, and feeding problems, 15%. The estimated PARs were: preterm, 0.74; IUGR, 0.55; sepsis, 0.55; asphyxia, 0.35; hypothermia, 0.08, and feeding problems, 0.04. The CF associated with the number of morbidities per neonate was: with no morbidity, 0.3%; one morbidity, 2.1%; two morbidities, 15.3%; three or more morbidities, 41.4% (p<0.001). In all, 82.5% of all deaths occurred in neonates with two or more morbidities. The proportion of total deaths associated with only preterm was 7.5%, and with only IUGR was 2.5%; however, with the main morbidity combinations it was preterm+sepsis, 35%; IUGR+sepsis, 22.5%; preterm+asphyxia, 20%; preterm+hypothermia, 15%; and preterm+feeding problem, 12.5%. The % CF with low birth weight (LBW) <2500 g alone was 5.2% and with infection alone was 1.9%, but with LBW+infection it was 31.9%. The estimated excess deaths caused by sepsis over and above LBW was 44% of the total deaths.

CONCLUSIONS:

Preterm and IUGR are ubiquitous components, but usually not sufficient to cause death. Most deaths occur due to a combination of preterm or IUGR with other comorbidities. If preterm birth or IUGR cannot be prevented, the strategy should be to ensure neonatal survival by addressing comorbidities, that is, infections, asphyxia, hypothermia, and feeding problems in that order of priority. We hypothesize that the prevention and/or management of neonatal infections will reduce neonatal mortality by 40 to 50%.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

State of the World's Newborns, Save the Children, Washington DC. 2001.

Bang AT, Paul VK, Reddy HM, et al. Why do neonates die in rural homes? Part I. J Perinatol 2005;25:S29–S34.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases. 9th Revision 1975. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1977.

Gray RH, Smith G, Barss P . The use of verbal autopsy methods to determine selected causes of death in children. Occasional Paper No. 10, Institute of International Programmes, The Johns Hopkins University, School of Hygiene and Public Health, Baltimore, February 1990.

Battle RM, Pathak D, Humble CG, et al. Factors influencing discrepancies between premortem and postmortem diagnoses. JAMA 1987;258:339–344.

Kircher T, Anderson RE . Cause of death: proper completion of the death certificate. JAMA 1987;258:349–352.

Rothman K, Greenland S . Causation and causal inference. In: Rothman K, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publ.; 1998. p. 7–28.

Greenland S, Rothman K . Measures of effect and measures of association. In: Rothman K, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadephia: Lippincott-Raven Publ.; 1998. p. 47–65.

Rowe AK, Powel KE, Flanders WD . Why population attributable fractions can sum to more than one. Am J Prev Med 2004;26 (30):243–249.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule S, Deshmukh M, Reddy MH . Burden of morbidities and the unmet need for health care in rural neonates — a prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. Indian Pediatr 2001;38:952–965.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM, et al. Methods and the baseline situation of the field trial of home-based neonatal care in Gadchiroli, India. J Perinatol 2005;25:S11–S17.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule S, Reddy MH, Deshmukh M . Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet 1999;354:1955–1961.

Bang AT, Reddy HM, Baitule SB, et al. Incidence of neonatal morbidities. J Perinatol 2005;25:S18–S28.

Kahn H, Sempos CT . Attributable risk. In: Kahn H, Sempos CT, editors. Statistical Methods in Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. p. 72–83.

Susser M . Prenatal nutrition, birth weight and psychological development: an overview of experiments, quasi-experiments and natural experiments in the past decade. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:784–803.

Krammer MS . Effects of energy and protein intakes on pregnancy outcome: an overview of research evidence from controlled clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;58:627–635.

Ramakrishnan U . Nutrition and low birth weight: from research to practice. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:17–21.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy MH, Baitule SB, et al. Simple clinical criteria to identify sepsis or pneumonia in neonates in the community. Ped Inf Dis J (in press).

National Neonatology Forum (NNF) of India. National Neonatal and Perinatal Data-base. New Delhi: NNF; 2000.

International Institute of Population Sciences. National Family Health Survery II (1998–99). Mumbai: International Institute of Population Sciences; 2000.

Registrar General of India. Sample Registration System, Government of India, New Delhi, 1998.

WHO. Essential newborn care: report of a technical working group 1994. Geneva: WHO; 1996.

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB . Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The financial support for this work came from The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation and Saving Newborn Lives Initiative, Save the Children, USA, and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bang, A., Reddy, H., Bang, R. et al. Why Do Neonates Die in Rural Gadchiroli, India? (Part II): Estimating Population Attributable Risks and Contribution of Multiple Morbidities for Identifying a Strategy to Prevent Deaths. J Perinatol 25 (Suppl 1), S35–S43 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211270

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211270

This article is cited by

-

Outcomes of neonatal hypothermia among very low birth weight infants: a Meta-analysis

Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology (2021)

-

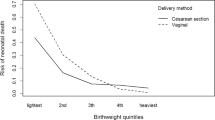

The Effect of Child’s Body Size at Birth on Infant and Child Mortality in India

Canadian Studies in Population (2019)

-

A Prospective Study of Causes of Illness and Death in Preterm Infants in Ethiopia: The SIP Study Protocol

Reproductive Health (2018)

-

Preterm birth and neonatal mortality in a rural Bangladeshi cohort: implications for health programs

Journal of Perinatology (2013)

-

Birth asphyxia as the major complication in newborns: moving towards improved individual outcomes by prediction, targeted prevention and tailored medical care

EPMA Journal (2011)