Abstract

Purpose

Cataract surgery in a patient with previous trabeculectomy is considered to have an adverse effect on the long-term survival of the filtering bleb. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used in patients with a pre-existing bleb, undergoing cataract surgery, but there are no published reports for or against its use in such cases. This study was carried out to evaluate the protective role of subconjunctival 5-FU on the pre-existing bleb from trabeculectomy in patients undergoing phacocoemulsification.

Methods

This retrospective study was carried out on patients with pre-existing filtering bleb from trabeculectomy for primary open-angle glaucoma who then underwent phacoemulsification at least 12 months after trabeculectomy. Data were collected for two groups of patients. Group 1 (22 patients) received 5-FU at the end of successful phacoemulsification, whereas group 2 (25 patients) did not receive it. The two groups were comparable with respect to age, gender, intraocular pressure (IOP), type of glaucoma, number of adverse risk factors present, and duration of follow-up. Any worsening of IOP control was analysed using mean IOP and mean change in the treatment for glaucoma.

Results

Mean IOP was comparable in the two groups, but there was a significant difference in mean change in glaucoma treatment between the two groups at 12 months postoperatively. Worsening of IOP control was seen in 13.6% of the patients in group 1 and in 36.4% in group 2 (P-value=0.03).

Conclusion

Our study suggests that 5-FU has a protective effect on the functioning bleb and may be used routinely at the end of phacoemulsification in such cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cataract surgery in a patient with previous trabeculectomy is generally considered to have adverse effect on the long-term survival of the filtering bleb. Kolker and Hetherington1 reported that 50% of blebs can fail after cataract surgery. Mietz et al2 suggested that cataract surgery had no markedly negative effect on the functioning bleb. Park et al3 suggested that impairment in intraocular pressure (IOP) control after clear corneal incision phacoemulsification, in eyes with previous trabeculectomy, is comparable to that in the natural course of trabeculectomy. The most widely held view is that cataract extraction by any technique performed in eyes with a previous filtering procedure will have an adverse effect on the previous filtering bleb.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The cause of this adverse effect is thought to be bleb failure owing to increased stimulus for fibrosis. This stimulus can come from postoperative inflammation or from conjunctival manipulation during phacoemulsification.

Use of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in failing blebs is well described with or without needling of the failing bleb.13, 14 This has been used in patients with pre-existing bleb undergoing cataract surgery, but there are no published reports for or against its use in such situation. There is, however, an abstract, published in the proceedings of ARVO in 1992, supporting this idea.15

5-FU in such cases was used for many years by one of the authors (PGC). This study was carried out to evaluate the role of subconjunctival 5-FU at the end of phacoemulsification in patients with previous trabeculectomy.

Methods

This retrospective comparative study was performed on patients with pre-existing filtering bleb from trabeculectomy for primary open-angle glaucoma. The practice of one of the authors (PGC) was compared to that of the other consultant ophthalmologists in the department who were not using 5-FU following phacoemulsification. These patients had undergone uncomplicated phacoemulsification through clear corneal incision, on the same eye at least 12 months after the trabeculectomy. Case notes of such patients were identified retrospectively from operating room records. Inclusion criteria were phacoemulsification with clear corneal incision, primary open-angle glaucoma patients with functioning bleb, patients with maximum of one adverse risk factor for bleb failure, minimum duration of 12 months between trabeculectomy and phacoemulsification, and minimum of 12-month follow-up after phacoemulsification.

The case notes were examined and data were collected for two groups of patients. Group 1 included patients who received subconjunctival injection of 5-FU at the end of successful phacoemulsification. Group 2 included patients who did not receive subconjunctival 5-FU after successful phacoemulsification. Preoperative data included age, sex, ethnicity, type of glaucoma, length of time between previous trabeculectomy and phacoemulsification, site and characteristics of bleb, any other glaucoma intervention, current glaucoma medication, visual acuity, IOP, and other systemic and ocular abnormalities. Exclusion criteria were age less than 60 years, any type of secondary open-angle glaucoma, previous trabeculectomy within the last 12 months, follow-up of less than 12 months, and poor documentation.

Method of administration of subconjunctival 5-FU was standard. At the end of successful phacoemulsification procedure, 0.2 ml of 5-FU (25 mg/ml) was injected above the pre-existing bleb with a short, sharp, disposable 29-gauge needle. The point of entry of needle was at least 8 mm away from the limbus. Copious irrigation with saline was then performed to wash away any residual 5-FU from the ocular surface. Follow-up data were collected for 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. Follow-up information included IOP measurements, change in glaucoma treatment, and change in bleb morphology. To determine the number of medications used, each different topical drug counted one point if used according to the manufacturer's suggestions. Systemic treatment with carbonic anhydrase inhibitor also counted one point. Any worsening of IOP control was analysed using the parameters of mean IOP and mean change in the treatment for glaucoma. Worsening of IOP control was considered if glaucoma medication was increased.

Results

Sixty case notes of primary open-angle glaucoma patients who had functioning filtering blebs from previous trabeculectomies and had then undergone phacoemulsification were identified. Twenty-two patients matched the inclusion criteria for group 1 and 25 patients matched the inclusion criteria for group 2. Baseline data of the two groups are given in Table 1. Mean age of the patients in group 1 was 76.9±7.6 (SD) and in group 2 was 77.5±9.5 (SD). In group 1, there were 11 female and 11 male patients. In group 2, there were 15 male and 10 female patients. In group 1, out of 22 patients included, there were 13 Caucasians, two Asians, and four Afro-Caribbeans, and ethnicity could not be identified from the case notes in three patients. In group 2, out of 25 patients, 15 were Caucasians, three Afro-Caribbeans, and two Asians. In five patients, ethnicity could not be ascertained. In group 1, 14 patients underwent surgery on the right eye and eight patients on the left eye. In group 2, right eye was operated on in 14 cases and left eye in 11 cases. Mean IOP, before phacoemulsification, was 14.7±3.7 (SD) in group 1 and 15.6±3.8 (SD) in group 2. Mean number of topical medications preoperatively was comparable in two groups. It was 0.41±0.73 (SD) in group 1 and 0.30±0.40 (SD) in group 2. The two groups had similar systemic profile, for example systemic hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

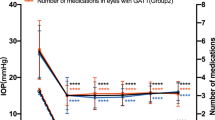

IOP profile and change in topical medications were compared in the two groups (Figures 1 and 2). The IOP profile of both groups is shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that mean IOP increased in the immediate postoperative period in both groups. In group 1, mean IOP came down almost to the preoperative level after the first month of the postoperative period, whereas in group 2, mean IOP remained higher than preoperative level throughout the study period, although difference in mean IOP was not statistically significant.

To analyse the worsening of IOP control, change in glaucoma medication for each patient in every group was calculated and tested statistically (independent sample t-test). The mean change in glaucoma treatment was calculated for each visit. This was compared at the end of 12 months and was −0.10±0.69 (SD) in group 1 and 0.44±0.55 (SD) in group 2 (Figure 3). The independent sample t-test was applied and results were significant when group 1 was compared to group 2 (P=0.02). Worsening of IOP control was also analysed by calculating the percentage of patients in whom glaucoma treatment was increased (Figure 4). In group 1, 13.6% patients required additional glaucoma treatment at 12 months, whereas in group 2, 36.4% required increase in glaucoma treatment at 12 months. Statistical test (independent sample t-test) showed a significant difference at 12 months postoperatively, when group 1 was compared to group 2 (P=0.03). One patient in group 2 experienced complete bleb failure and required repeat trabeculectomy to control the IOP.

Discussion

Cataract extraction causes partial or complete failure of pre-existing filtering blebs.1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 A recent study concluded that phacoemulsification significantly increased IOP and the number of glaucoma medications in eyes with pre-existing functioning filtering blebs.16 Spaeth and Fellman17 correlated the effect of cataract surgery on the IOP with the functioning of bleb. In situations where the bleb is not working at all, the eye will have a postoperative pressure profile similar to that in a patient without any filtering bleb. In eyes with partial bleb function, the final postoperative IOP tends to be around 50% higher than it was preoperatively. In eyes with thin, polycystic, and anterior bleb (often associated with an IOP around 5–8 mmHg on no antiglaucoma therapy), uncomplicated cataract extraction is unlikely to have any damaging long-term effect on the level of IOP.17 Postoperative intraocular inflammation is considered the most likely cause of failure of filtering blebs following cataract surgery.

5-FU subconjunctival injections have been used in failing blebs with or without the needling of bleb.13, 14, 16 The published data suggest that bleb needling augmented with 5-FU is a safe and effective method by which a significant number of failed or failing filtration blebs can be rescued from failure.13, 14, 16 There are no published reports regarding the role of 5-FU after cataract surgery in eyes with pre-existing drainage blebs. However, Johnstone et al15 in a poster presentation showed that survival of the bleb increased significantly following cataract surgery if adjunctive low-dose 5-FU was used around the area of bleb during the first 2 weeks after cataract surgery. This was a retrospective study comparing two groups. One group received 5-FU and other did not. They compared the IOP profile and change in glaucoma medication to assess the function of the bleb. The cataract surgery technique is not clear from the abstract, but probably it was extracapsular cataract extraction.15

In our study, we looked at cases of primary open-angle glaucoma that had trabeculectomy and subsequently underwent phacoemulsification. It is clear from our study that the need to use additional glaucoma treatment was significantly more if 5-FU was not used as an adjunct to phacoemulsification to protect the functioning bleb. The 5-FU injection was used at the end of phacoemulsification. Standard precautions in the technique of 5-FU injection were taken. We used the same concentration of 5-FU that we use with needling of a failing bleb. We did not experience any corneal toxicity in any of the cases. This study shows that phacoemulsification in patients with previous trabeculectomy had an adverse effect on the bleb function. This adverse effect was considerably less in group 1, where 5-FU was used at the end of phacoemulsification.

However, this study has several limitations. This was a retrospective study. Mean number of medications is not a good measure of the success or failure of a procedure with such small numbers of patients. A prospective, randomized trial with large number of cases may answer this question more appropriately. Despite its limitation, this study suggests a protective role of 5-FU on functioning blebs during phacoemulsification and may be used routinely at the end of phacoemulsification in patients with functioning bleb from previous trabeculectomy. This study emphasizes the need for further research on this subject.

References

Kolker AE, Hetherington J . Becker–Shaffer's Diagnosis and Therapy of the Glaucomas, 4th ed. Mosby: St Louis, 1976.

Mietz H, Andresen A, Welsandt G, Krieglstein GK . Effect of cataract surgery on intraocular pressure in eyes with previous trabeculectomy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001; 239 (10): 763–769.

Park HJ, Weitzman M, Caprioli J . Temporal corneal phacoemulsification combined with superior trabeculectomy. A retrospective case–control study. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115 (3): 318–323.

Swamynathan K, Capistrano AP, Cantor LB, WuDunn D . Effect of temporal corneal phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in eyes with prior trabeculectomy with an antimetabolite. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (4): 674–678.

Halikiopoulos D, Moster MR, Azuara-Blanco A, Wilson RP, Schmidt CM, Spaeth GL et al. The outcome of the functioning filter after subsequent cataract extraction. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 2001; 32: 108–117.

Crichton AC, Kirker AW . Intraocular pressure and medication control after clear corneal phacoemulsification and AcrySof posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in patients with filtering blebs. J Glaucoma 2001; 10: 38–46.

Rebolleda G, Munoz-Negrete FJ . Phacoemulsification in eyes with functioning blebs: a prospective study. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 2248–2255.

Casson RJ, Riddell CE, Rahman R, Byles D, Salmon JF . Long-term effect of cataract surgery on intraocular pressure after trabeculectomy: extracapsular extraction versus phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002; 28 (12): 2159–2164.

Casson R, Rahman R, Salmon JF . Phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation after trabeculectomy. J Glaucoma 2002; 11 (5): 429–433.

Dickens MA, Cahwell LF . Long-term effect of cataract extraction on the function of an established filtering bleb. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1996; 27: 9–14.

Chen PP, Weaver YK, Budenz DL, Feuer WJ, Parrish II RK . Trabeculectomy function after cataract extraction. Ophthalmology 1998; 105: 1928–1935.

Seah SK, Jap A, Prata Jr JA, Baerveldt G, Lee PP, Heuer DK et al. Cataract surgery after trabeculectomy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1996; 27: 587–594.

Broadway DC, Bloom PA, Bunce C, Thiagarajan M, Khaw PT . Needle revision of failing and failed trabeculectomy blebs with adjunctive 5-fluorouracil: survival analysis. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (4): 665–673.

Ophir A, Wasserman D . 5-Fluorouracil-needling and paracentesis through the failing filtering bleb. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 2002; 33 (2): 109–116.

Johnstone MA, Ziel CJ . Cataract surgery in the presence of a filtering bleb with postoperative 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992; 33: 948.

Allen LE, Manuchehri K, Corridan PG . The treatment of encapsulated trabeculectomy blebs in an out-patient setting using a needling technique and subconjunctival 5-fluorouracil injection. Eye 1998; 12 (Part 1): 119–123.

Spaeth GL, Fellman RL . Cataract extraction in patients with glaucoma. In: Duane's Ophthalmology, CD-ROM Edition. Clinical volume 6, chapter 16, 2001, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors has a financial or proprietary interest in any method or material mentioned

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, T., Arora, S. & Corridan, P. Phacoemulsification in patients with previous trabeculectomy: role of 5-fluorouracil. Eye 21, 780–783 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702327

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702327

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phacoemulsification after trabeculectomy in uveitis associated with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: intermediate-term visual outcome, IOP control and trabeculectomy survival

BMC Ophthalmology (2022)

-

Glaucoma control after phacoemulsification in eyes with functioning glaucoma filtration surgeries: trabeculectomies versus glaucoma drainage devices

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2022)

-

The Effect of Phacoemulsification on Intraocular Pressure in Eyes with Hyperfiltration Following Trabeculectomy: A Prospective Study

Advances in Therapy (2018)

-

Long-term effect of phacoemulsification on trabeculectomy function

Eye (2015)

-

Glaukom und Katarakt

Der Ophthalmologe (2010)