Abstract

Purpose

To document a previously unreported complication after vitrectomy with peeling of the internal limiting membrane (ILM) for idiopathic macular holes.

Method

Retrospective review of notes of 232 consecutive patients who underwent vitrectomy with peeling of the ILM for idiopathic macular holes from 1996 to 2001. Four patients were found to have eccentric iatrogenic macular holes postoperatively. Optical coherence tomography was used to evaluate these holes.

Results

The idiopathic macular holes were graded from stages II to IV preoperatively with visual acuities from 6/18 to 6/60. All patients had surgery within 6 months of presentation. They underwent vitrectomy with complete separation of the posterior cortical vitreous, peeling of the ILM, injection of platelets (0.1 ml), and gas tamponade with SF6 20%. Postoperatively the patients postured strictly face down for 10 days. Follow-up ranged from 8 months to 6 years. Iatrogenic eccentric macular holes were noted postoperatively. The holes were located between 3 and 6 o’clock in three patients and at 9 o’clock in the fourth patient, relative to the macula. Optical coherence tomography showed them to be full thickness and completely flat. No further intervention was necessary. No complications have arisen during follow-up.

Comment

To our knowledge iatrogenic eccentric full thickness macular holes after macular hole surgery have never been reported. We believe that the location of the holes represents the initial site of ILM elevation. These holes are asymptomatic, have not required any treatment and have not caused any complications in up to 6 years of follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We document a previously unreported complication following vitrectomy with peeling of the internal limiting membrane (ILM) for idiopathic macular holes. Macular holes were first reported in the late 1800s by Knapp and later by Noyes.1 The majority of macular holes seen in clinical practice are senile idiopathic holes but they can also occur secondary to trauma, inflammation, retinal vascular disease, cystoid macular oedema, macular pucker, or retinal detachment. To our knowledge iatrogenic macular holes following surgery have not been reported.

Report of cases

We retrospectively reviewed the notes of 232 consecutive patients who underwent vitrectomy with peeling of the ILM in our department for idiopathic macular holes from 1996 to 2001. Four patients were found to have developed eccentric macular holes following surgery. Three patients were female and one male, aged 56–79 years (mean 72 years). The macular holes were graded from stage II to IV preoperatively and visual acuity ranged from 20/60 to 20/200. All patients had surgery within 6 months of presentation. One experienced vitreoretinal surgeon performed all the operations (RB). Surgery consisted of standard pars plana vitrectomy with complete separation of the posterior cortical vitreous. After completion of the posterior vitrectomy, fluid air exchange was performed with a flute over the optic disc. Trypan blue was then injected with a Grizzard cannula under air, to stain the ILM prior to peeling. Subsequently, the ILM was elevated with Eckhart's forceps to lift, tear, and peel the membrane in a clockwise direction around the fovea. In order to control the circular peel it was necessary to regrasp the ILM at intervals. All patients had injection of platelets (0.1 ml) over the fovea with a Grizzard cannula and gas tamponade with SF6 20%. There were no reported intraoperative complications. Postoperatively the patients postured strictly face down for 10 days. Follow-up ranged from 8 to 72 months (mean 34 months).

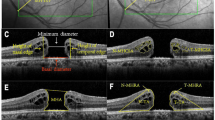

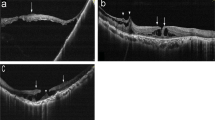

Four patients were found to have eccentric iatrogenic macular holes postoperatively (Figure 1). The holes were noted between 3 and 6 months postoperatively and were located between 4 and 6 o'clock in three patients and at 9 o'clock in the fourth patient, relative to the fovea. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed to image all the holes (Figure 2).

OCT showed the holes to be full thickness and completely flat. There was no demonstrable effect on visual acuity. No further intervention was deemed necessary and no complications have arisen during follow-up.

Comment

Idiopathic macular holes are a significant cause of central visual loss in people over the age of 55 years, particularly women.1 The natural history of idiopathic macular holes suggests that 50% of stage I holes resolve spontaneously, the other half progress to a stage II full-thickness macular hole.1, 2, 3 Pars plana vitrectomy with posterior cortical separation and gas tamponade is the standard procedure for idiopathic macular holes, stages II–IV.3, 4, 5 Reported complications of the surgery include RPE changes, subretinal neovascular membranes, cataracts, peripheral retinal breaks, retinal detachment, peripheral field defects, endophthalmitis, and raised intraocular pressure.2, 3, 4, 5 To our knowledge iatrogenic eccentric full thickness macular holes after macular hole surgery have not been reported. We believe that the formation and location of these iatrogenic macular holes represents trauma to the underlying layers of the retina while grasping the ILM with Eckhart's forceps, either at the initial site of ILM elevation or subsequent regrasping of the membrane. These holes are not obvious at the time of surgery although small areas of haemorrhage, which develop during peeling of the ILM, may possibly indicate the site of subsequent hole formation.

Other plausible mechanisms for the formation of these holes include damage from a jet of injected trypan blue or inadvertent trauma to the retina by the intraocular instruments, although we feel this is unlikely.

After the original insult, these areas organize and leave a flat well-demarcated, full-thickness macular hole. The iatrogenic eccentric holes seen in our patients have been completely asymptomatic, have remained stable and not required any treatment in up to 6 years of follow-up. We would recommend no further intervention for patients with eccentric iatrogenic macular holes found postoperatively, as these appear unlikely to progress to retinal detachment.

References

Gass JDM . Idiopathic senile macular hole: its early stages and pathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol 1988; 106: 629–639.

Benson WE, Cruickshanks KC, Fong DS, Williams GA, Bloome MA, Frambach DA et al. Surgical management of macular holes: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 1328–1335.

Freeman WR, Azen SP, Kim JW, el-Haig W, Mishell DR III, Bailey I . Vitrectomy for the treatment of full-thickness stage 3 or 4 macular holes. Results of a Multicentered Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115: 11–21.

Kelly NE, Wendel RT . Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes: results of a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109: 654–659.

Johnson MW . Improvements in the understanding and treatment of macular holes. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2002; 13: 152–160.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented at The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology—ARVO meeting 2002.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rubinstein, A., Bates, R., Benjamin, L. et al. Iatrogenic eccentric full thickness macular holes following vitrectomy with ILM peeling for idiopathic macular holes. Eye 19, 1333–1335 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701771

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701771

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Postoperative eccentric macular holes after surgery for vitreomacular interface diseases

International Ophthalmology (2020)

-

Recurrence rate and need for reoperation after surgery with or without internal limiting membrane removal for the treatment of the epiretinal membrane

International Journal of Retina and Vitreous (2017)

-

Postoperative eccentric macular holes after vitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling

International Ophthalmology (2017)

-

Eccentric Macular Hole after Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Epiretinal Membrane Without Internal Limiting Membrane Peeling: A Case Report

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2017)

-

Associated factors and treatment outcome of presumed noninfectious endophthalmitis occurring after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2013)