Abstract

Purpose To evaluate the characteristics of patients with nonorganic or medically unexplained visual loss (MUVL) presenting to a neuro-ophthalmology clinic.

Methods A retrospective review of the case notes of patients identified from our diagnostic register. All patients had been followed up for at least 18 months and investigations (including, in all cases, neuroimaging) had failed to reveal any underlying pathology. To be included, patients had to have at least one inconsistent feature on visual function testing.

Results: We identified 58 patients with MUVL. A total of 79% of patients were female and 21% were male. In total, 36% of patients had been seen in other medical specialties with unexplained symptoms. In all, 60% of patients complained of glare or pain. Of the patients with bilateral visual loss, the acuities were frequently the same in each eye and the most common pattern of visual field loss was concentric contraction. Those with unilateral visual loss had a more variable pattern of visual failure. In total, 22% of patients showed some visual recovery though this was usually incomplete. In one patient, organic pathology accounting for the visual symptoms became apparent after the end of the 18 month follow-up period.

Conclusions Medically unexplained symptoms, in general, form an important part of the workload in most medical specialties. Unexplained symptoms in ophthalmology have not been well studied. Terminology should be brought into line with that used in other medical specialties. Further work may help in the identification of positive diagnostic features of MUVL which should not be simply a ‘diagnosis of exclusion’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with medical symptoms without any apparent physical cause, are a common problem in medical practice and in some medical specialties may be the most common reason for presentation.1

In common with other authors, we prefer the term ‘medically unexplained symptoms’ to ‘functional’ or ‘hysterical’ symptoms, because it is purely descriptive and makes no aetiological assumptions.2

Patients with medically unexplained visual loss (MUVL) are commonly referred to the neuro-ophthalmic service on the assumption that if there is no visible pathology there must be an underlying neurological cause for their visual loss.

We aimed to examine the characteristics of adult patients with MUVL presenting to the neuro-ophthalmology clinic at the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle.

Methods

Patients with MUVL were indentified from our diagnostic register and the notes examined to determine the demographic characteristics and patterns of visual loss.

We recorded whether patients had been under the care of psychiatrists or were receiving anxiolytics, antidepressants, or antipsychotics. General medical notes were reviewed looking for evidence of medically unexplained symptoms in other medical specialties. Wherever possible the caring physician was contacted to discuss the case.

We defined MUVL as reduced vision without any identifiable physical cause and at least one inconsistent feature on visual function testing. We excluded those under 16 years of age and a minimum of 18 months follow-up was required.

All patients underwent assessment of visual acuity for near and distance, subjective and objective refraction, visual field testing, and colour vision measured with the Ishihara charts. The remaining tests depended on the exact pattern of visual loss and were chosen to identify inconsistent features in the patient's visual function. They included:

-

Visual acuity at 6, 3, and m. Finding that the same Snellen line was read at 6 m and 3 m was regarded as inconsistent.

-

Confrontation fields at ½ and 2 m or tangent screen visual fields at 1 and 2 m to elicit tubular visual fields.

-

Goldmann fields: Looking for loss of normal progression of isopter sizes as target size and brightness was reduced, or spiralling of isopters. We defined concentric contraction as a field of less than 20° to the V4e target and abnormal isopter progression as a less than 5° gap between the V4e and the I4e target.

-

Four dioptre base out prism tests while fixating a Snellen letter to lines better than the measured visual acuity. If a movement was detected by the examiner or the patient was aware of diplopia, an acuity approximately equal to that Snellen letter was assumed.

-

Stereoscopic tests: A stereoacuity of 40 s of arc was assumed to be equivalent to an acuity of 6/6 Snellen in either eye.

-

Fogging tests: Plus lenses of gradually increasing power were placed before the unaffected eye, with both eyes open, while the vision was measured unknown to the patient with the affected eye.

-

Normal electrodiagnostic testing was not a criterion for diagnosing MUVL.

Results

We identified 58 patients with MUVL who had been followed up for at least 18 months (range 18 months to 7 years). The characteristics of these patients are summarised in Table 1.

In all, 34 patients were referred by other consultants within our unit, 11 were referred by consultants at other hospitals, and 13 were directly referred by their general practitioner.

A total of 46 (79%) patients were female and 12 (21%) were male. In total, 18 (31%) had a past history of psychiatric problems. Visual loss was accompanied by pain or glare in 60% of patients. Descriptions of the pain were often florid but there were no consistent features. A total of 13 patients showed some improvement in vision over the study period although this was only complete in two cases. We classified our patients according to according to whether one or both eyes were affected. The characteristics of each group are outlined below.

Bilateral visual loss

In all, 39 patients complained of visual loss in both eyes, 33 (85%) patients were female and 6(15%) male. The age range was 17–76 years and the median age was 42 years.

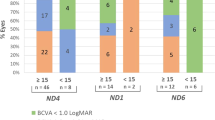

The median level of visual acuity was 6/18 with a range of 6/9 to count fingers at one metre (Figure 1).

In total, 16 (41%) patients had been seen in other medical specialties with unexplained medical symptoms. A total of 33 (33%) had prior exposure to ophthalmic services with what appeared to be organic pathology.

Of the bilateral group, 14 (36%) had a past history of psychiatric problems, 21 (53%) patients complained of glare or pain.

The most common pattern of visual loss was concentric contraction, which was found in 30 patients (77%). In 11 of these cases, the isopter progression was abnormal and in four cases the fields were tubular. In one case, the fields were noted to spiral inwards. The remaining patients had patchy increases in threshold on the Humphrey 24 : 2 testing, three patients; normal fields, four patients; nasal field loss, one patient; and temporal field loss, one patient. Only five patients (13%) showed any improvement in vision over the study period.

Unilateral visual loss

In total, 19 patients complained of visual loss in one eye only. The age range was 16–65 years and the median age was 30 years. There were 12 (63%) female and seven (37%) male patients.

The median level of visual acuity was 6/36 and the range was 6/9 to no perception of light (Figure 2).

Five patients (26%) had been seen with unexplained medical symptoms in other medical specialties. Seven patients (37%) of the unilateral group had prior exposure to ophthalmic services with what appeared to be organic pathology. Four (21%) of the unilateral group had a past history of psychiatric problems and 14 (73%) complained of pain or glare. The patterns of visual field loss were more variable in the unilateral visual loss group.

Six (32%) patients showed concentric contraction, in three of these cases, the configuration was tubular. In six cases, the visual fields were full. The remaining cases had patchy field loss that was mostly peripheral and on both sides of the vertical meridian. Eight patients (43%) showed improvement in vision over the study period.

Discussion

Patients with medical symptoms and no identifiable pathology to account for them constitute a considerable part of the workload in both primary and secondary care3 and are often frequent attenders at medical clinics.4 In many cases, the symptoms persist and cause considerable distress and anxiety. Patients with medically unexplained symptoms may be as disabled as those with identifiable causes for their symptoms.5

The terminology surrounding unexplained medical symptoms has been discussed extensively by other authors.2, 3 The terms ‘hysterical’ and ‘psychosomatic’ imply a psychological process of converting psychological distress into somatic symptoms. The two terms imply knowledge that the observer does not have. The term ‘malingering’ implies conscious deception and has been characterized as ‘more of an accusation than a diagnosis’; we suspect that it is rare in ophthalmic practice.

The terms ‘functional’ or ‘nonorganic’ are more acceptable because they do not presuppose an unverified underlying psychological process. But, in common with other authors1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 we prefer the term ‘medically unexplained symptoms’ (in this case ‘visual loss’), because it is free from aetiological assumptions and does not preclude the possibility of some undetected organic pathology.

It is unsafe to define unexplained visual loss purely on the basis of inconsistencies in the pattern of visual loss. We have frequently observed these in patients with unequivocal organic pathology, such as visual loss due to craniopharyngiomas and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The search for inconsistencies with a series of catch tests can also add a confrontational tone to consultation and such tests need to be approached with caution. We based the diagnosis of MUVL on normal clinical examination, non physiological patterns of visual loss, normal investigations, and a period of observation of at least 18 months.

There do seem to be some clear patterns among our patients. The first, and most easily identifiable category, is those with bilateral visual loss. The symmetry between the two eyes is striking with the same acuity in each eye in most cases. In many of these patients, the field loss was either tubular in nature, or normal progression of isopters was not apparent when different target sizes were used. This pattern of visual loss has been well described by other authors who also found that it was rarely associated with underlying pathology.11, 12 The second category is those with unilateral visual loss. The pattern of visual loss was more variable, although concentric contraction of the visual field was still the most common pattern observed. The visual acuities tended to be worse in the unilateral visual loss group. Central scotomas were not found in either group and we believe that they are almost invariably associated with organic pathology whether any is visible or not.

We accept that some of our patients may have as yet undetected organic pathology to account for their visual problems. Other studies have shown that patients with medically unexplained symptoms rarely turn out to have organic pathology.5, 8 In our series, one patient in the bilateral visual loss group, with concentric contraction of Goldmann visual fields, was subsequently diagnosed as having Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease may present with visual field loss13 and more commonly field defects are recognised during the course of the disease.14, 15 However, presentation with reduced visual acuity is unusual.

Previous studies on adult patients with medically unexplained symptoms have pointed to certain childhood risk factors. These include prior experience of illness in close family members, unexplained medical symptoms, particularly abdominal pain, and parental neglect.9 It is difficult to address these risk factors in a retrospective study such as ours. However, a large proportion of patients, particularly in the bilateral visual loss group had been previously investigated for unexplained symptoms elsewhere. These included unexplained chest pains, joint pain, abdominal discomfort, numbness, pseudoseizures, gait abnormalities, and speech disorders. We suspect that our figure of 38% having unexplained symptoms in other medical specialties is an underestimate, as some patients had acquired diagnostic labels such as ‘fibromyalgia’ and ‘irritable bowel syndrome’, which themselves raise questions regarding organic aetiology.

Surprisingly, a higher prevalence of psychiatric problems has not been consistently demonstrated in patients with medically unexplained symptoms. In common with other authors, we have found that at least 60% of our patients do not appear to have any psychiatric morbidity that might account for their symptoms.16 This does not fit with the conversion or hysterical model of unexplained medical symptoms. We may have underestimated the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity as our criterion was whether the patients were receiving or had received anxiolytics or psychotropic medication or had been under the care of a psychiatrist in the recent past.

Other authors describing patients with MUVL have suggested that it is increased suggestibility that distinguishes these patients from those with organic disease.16, 17 Evidence of suggestibility can sometimes be seen on examination. For example, by suggesting that the earlier plates of the Ishihara pseudoisochromatic test were more difficult than the later plates, three patients could be induced to read the last six plates correctly but not the first contrast plate. Again, some caution is required; patients with organic pathology are often anxious to please and may consequently appear suggestible.

Only 22% of our patients showed any improvement in their visual function over the follow-up period. This is much less than the figure reported by Kathol et al18 in a series of 42 patients in whom 60% showed improvement in visual function.18 This may be because the two series are not comparable. Alternatively, changes in working practice may have made our patients more resistant to treatment. The advent of subspecialisation means that most of our patients had seen multiple different physicians and been extensively investigated. There is evidence that this process can itself reinforce the belief that there may be serious underlying medical problems and that excessive investigation may be an iatrogenic factor in the development of medically unexplained symptoms.19

We have not discussed the utility of electrophysiological testing in these patients. There is no doubt that it can reveal subtle pathology missed by clinical examination such as Batten's disease or Stargardt's disease, though neither of these is likely in the age group we studied. Some authors describe a discrepancy between P-VEP measured acuities and Snellen visual acuities in patients with functional visual loss.20 However, the use of pattern evoked potential (P-VEP) in the diagnosis of nonorganic visual loss is controversial as many subjects can alter or extinguish their P-VEP.21, 22 Therefore, P-VEP cannot be used with certainty to distinguish between organic and non organic visual loss.

Unexplained or functional visual loss is a common problem in ophthalmology.6 Most ophthalmologists are likely to encounter the problem in their practice. It consumes large amounts of resources and generates anxiety in patients and their carers. It appears to have similar risk factors to medically unexplained symptoms in other medical specialties. We believe that terminology should be brought into line with that used in other specialties. Further research will require carefully planned prospective studies.

References

Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S . Medically unexplained symptoms: An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosomatic Res 2001; 51: 361–367.

Wilkie A, Wessely S . Patients with medically unexplained symptoms. B J Hosp Med 1994; 51: 421–427.

Anon . What to do about medically unexplained symptoms. Drug Ther Bull 2001; 39(1): 5–7.

Smith GR, Monson RA, Ray DC . Patients with multiple unexplained symptoms. Arch Intern Med 1986; 146: 69–72.

Carson AJ, Ringbauer B, Stone J, Mckenzie L, Warlow C, Sharpe M . Do medically unexplained symptoms matter? prospective cohort study of 300 new referrals to neurology outpatients clinics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 68: 207–210.

Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, Hotopf M . Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. B Med J 2001; 322:1–4.

Sharpe M, Carson A . Unexplained" somatic symptoms, functional syndromes, and somatization: do we need a paradigm shift. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 926–930.

Crimlisk H, Bhatia K, Cope H, David A, Marsden C, Ron M . Slater revisited: a six year follow up of patients medically unexplained motor symptoms. B Med J 1998; 316: 582–586.

Hotopf M, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, Wessely S . Childhood risk factors for adults with medically unexplained symptoms: results form a national birth cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156: 1796–1800.

Katon WJ, Walker EA . Medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(Suppl 20): 15–21.

Hurst A, Symms J . Narrow and Spiral fields of vision in hysteria, malingering and neurasthenia. Br J Ophthalmol 1919; 3: 17.

Rowland W, Rowe A . Marked concentric contraction of the visual fields: a study of 100 consecutive cases. Trans Am Acad of Ophthalmol 1929; 34: 107–114.

Whittaker K, Burdon M, Shah P . Visual field loss and Alzheimer's disease. Eye 2002; 16: 206–208.

Armstong R . Visual field defects in Alzheimers disease. Optometry Vision Sci 1996; 73: 677–682.

Trick G, Trick L, Morris P, Wolf M . Visual field loss in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurology 1995; 45: 68–74.

Kathol R, Cox T, Corbett J, Thompson H, Clancy J . Functional visual loss: I. A true psychiatric disorder? Psychol Med 1983; 13: 307–314.

Thompson H . Functional visual loss. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 100: 209–213.

Kathol R, Cox T, Corbett J, Thompson H . Functional visual loss: follow up of 42 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 1983; 101: 729–735.

Mayou R, Farmer A . ABC of psychological medicine: functional somatic symtoms and syndromes. Br Med J 2002; 325: 265–268.

Xu S, Meyer D, Yoser S, Mathews D, Elfervig J . Pattern Visual Evoked Potential in the diagnosis of functional visual loss. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 76–81.

Morgan R, Nugent B, Harrison J, O'Connor P . Voluntay alteration of pattern visual evoked responses. Ophthalmology 1985; 92: 1356–1363.

Bumgartner J, Epstein C . Voluntaty alteration of visual evoked potentials. Ann Neurol 1982; 12: 475–478.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Griffiths, P., Eddyshaw, D. Medically unexplained visual loss in adult patients. Eye 18, 917–922 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701367

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701367

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Contribution of objectively measured grating acuity by sweep visually evoked potentials to the diagnosis of unexplained visual loss

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2022)

-

Medically unexplained visual symptoms in children and adolescents: an indicator of abuse or adversity?

Eye (2009)