Abstract

We investigated infant feeding habits in relation to risk of childhood central nervous system tumours among 633 cases in the UK Childhood Cancer Study (UKCCS). No significant effect of breastfeeding was detected overall (odds ratio 1.01, confidence interval: 0.85–1.21) nor in any morphological subgroup. Similarly, no effect for the duration of breastfeeding or any other feeding practices was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Central nervous system (CNS) tumours are the second most common group of childhood cancers after leukaemia. Rare genetic disorders can predispose children to a small proportion of CNS tumours, (Bondy, 1991; Little, 1999) but attempts to identify underlying environmental risk factors have largely been unsuccessful, with only ionising radiation known to confer an increased risk (Linet et al, 2003).

Childhood leukaemia may have an infectious aetiology (McNally and Eden, 2004) but reported links between childhood leukaemia and breastfeeding (reviewed by Guise et al, 2005) are inconsistent (Dockerty et al, 1999; Shu et al, 1999; Rosenbaum et al, 2000; Beral et al, 2001).

Interest in a link between childhood CNS tumours and infections has arisen from epidemiological analyses (Nyari et al, 2003; Altieri et al, 2006; Shaw et al, 2006) and excess space–time clustering and seasonality of cases (McNally et al, 2002), though not all these findings have been replicated (McNally et al, 2004). There is an apparent dearth of studies investigating the effect of breastfeeding on childhood CNS tumours. Schuz et al (2001) have reported no effect of breastfeeding on the risk of childhood CNS tumours whereas other studies have similar results for a broad group of ‘other cancers’ containing CNS tumours (Mathur et al, 1993; Beral et al, 2001; Lancashire and Sorahan, 2003). The likely differences in aetiology between CNS cancer types mean any subgroup-specific effect of feeding habits may have been masked. This study examines the effect of feeding habits for all CNS tumours, but also by diagnostic subgroup to address possible differences in aetiology.

Patients and methods

The UKCCS is a nationwide population-based case–control study of childhood malignancies established with the aim of identifying risk factors for childhood cancer. Details of the study are published elsewhere (UKCCS Investigators, 2000). Briefly, children diagnosed with cancer before 15 years of age were eligible for inclusion between 1991–1994 for all diagnoses in Scotland and 1992–1996 in England and Wales. Cases of solid tumours, including CNS tumours were recruited to 1994. A pathological review provided detailed classification of tumours. Two controls per case were selected at random from health authorities/health boards and matched by birth month/year and study region, non-participating controls were replaced.

Mothers of case and control subjects were interviewed using a questionnaire detailing whether they had ever breastfed, including dates and durations, whether they had ever used formula milk, whether they sterilised bottles and feeding utensils, and the age at which solid food was introduced.

A total of 7621 controls and 686 cases were available for the study. Children under 12 months of age (51 CNS cases, 631 controls) at diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis were excluded to prevent bias caused by premature cessation of breastfeeding owing to cancer. Children were also excluded where the questionnaire was not completed by the biological mother (two cases, 35 controls).

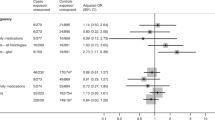

Analyses were carried out for all CNS tumours (n=633), and diagnostic subgroups; all gliomas (n=347) (including pilocytic astrocytoma (n=160)), ependyoma (n=65), medulloblastoma/PNET (n=149), and other CNS tumours (n=72). The comparison control group included all controls from the entire study, a procedure common to all UKCCS studies (Beral et al, 2001).

Odds ratios (OR) were estimated using unconditional logistic regression and were adjusted for age (in one year intervals), sex, study region, and Townsend deprivation index (Townsend et al, 1988) derived from the residential address at diagnosis. Analyses were undertaken investigating the effect of breastfeeding, sterilising feeding utensils, and the age at which the child was first introduced to solid food.

Results

Overall, the proportion who had ever been breastfed was very similar between cases and controls (64.1% cases vs 63.5% controls), as was the proportion breastfed for over 6 months (26.4 vs 26.5%).

ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of breastfeeding on CNS tumour risk can be seen in Table 1. No significant associations were observed between ever having breastfed and all CNS tumours or any diagnostic subgroup, nor was there any statistically significant effect of duration of breastfeeding. The OR of developing any CNS tumour is 1.01 (CI: 0.85–1.21) of ever having been breastfed to never having been breastfed, and for over 6 months compared to never is 1.02 (CI: 0.82–1.27).

Mothers of controls who breastfed only did so on average for 11.6 months compared to 3.6 months in mothers who also used formula feed (t-test; P<0.001). Women who formula fed also introduced their children to solid food earlier at 3.9 months compared to 4.3 months in women who only breastfed (among controls) (t-test; P<0.01). Breastfeeding habits differed greatly according to Townsend deprivation category; areas exhibiting the highest levels of deprivation showed the lowest level of breastfeeding (χ2 trend test P<0.001; Altman, 1991). Birth order also influenced breastfeeding habits, with later children being less likely to have been breastfed (χ2 trend test P<0.001). Older children were less likely to have been given formula feed (χ2 trend test, 1 year age intervals, P=0.001) but no more likely to have been breastfed (P=0.181); it is unclear whether this constitutes bias or a shift in feeding habits.

None of the further analyses of sterilisation or age at introduction of solid food showed a significant effect for all CNS tumours or any diagnostic subgroup (results not shown), although an increased risk associated with sterilising feeding utensils did approach significance (OR 1.54, P=0.067, CI: 0.97–2.45). Analyses repeated using a matched design (1251 controls) obtained similar results (results not shown).

Discussion

Our results provide no evidence to suggest breastfeeding either positively or negatively influences the risk of childhood CNS cancers. No effects of ever breastfeeding or of the duration of breastfeeding were observed. Our findings are consistent with Schuz et al (2001) although based on larger numbers and analysed by diagnostic subgroups. However, if CNS tumours do have an infectious aetiology, these results may not translate to developing countries, where the protective effect of breastfeeding against infection is likely to be more significant (WHO Collaborative Study Team, 2000).

Case–control studies are vulnerable to bias (Rothman, 1998) and the UKCCS is subject to participation bias; responding controls are generally from less deprived areas and therefore are not completely representative of the underlying population (Law et al, 2002). Areas of higher deprivation display a lower level of breastfeeding (Wright et al, 2005); this is also shown in our results. Despite attempts to adjust for deprivation it is possible that a confounding effect may remain. Recall bias is also a potential problem, with the possibility of differential reporting between cases and controls. Self-reporting of breastfeeding habits are known to lack accuracy (DHS Comparative Studies, 1999), though it is unclear whether this differs between cases and controls.

Whether or not the mother had ever sterilised feeding utensils approached significance. This result is driven by differences between case and control mothers who have solely breastfed; owing to multiple comparisons it is possible this has occurred by chance.

In summary, this study found no evidence that breastfeeding and other infant feeding habits influence the risk of childhood CNS tumours.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Altieri A, Castro F, Lorenzo Bermejo J, Hemminki K (2006) Association between number of siblings and nervous system tumors suggests an infectious etiology. Neurology 67: 1979–1983

Altman DG (1991) Chapter 10. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman and Hall/CRC

Beral V, Fear NT, Alexander F, Appleby P, UKCCS Investigators (2001) Breastfeeding and childhood cancer. Br J Cancer 85 (11): 1685–1694

Bondy M, Lustbader ED, Buffler PA, Schull WJ, Hardy RJ, Strong LC (1991) Genetic epidemiology of brain cancer. Genet Epidemiol 8: 253–267

DHS Comparative Studies (1999) Breastfeeding and complementary infant feeding, and the postpartum effects of breastfeeding. Demographic and Health Surveys Comprehensive Studies No. 30, Macro International Inc, Maryland, USA

Dockerty JD, Skegg DC, Elwood JM, Herbison GP, Becroft DM, Lewis ME (1999) Infections, vaccinations, and the risk of childhood leukaemia. Br J Cancer 80: 1483–1489

Guise J-M, Austin D, Morris CD (2005) Review of case–control studies related to breastfeeding and reduced risk of childhood leukemia. Pediatrics 116 (5): e724–e731

Lancashire RJ, Sorahan T (2003) OSCC. Breastfeeding and childhood cancer risks: OSCC data. Br J Cancer 88: 1035–1037

Law GR, Smith AG, Roman E, UKCCS Investigators (2002) The importance of full participation: lessons from a national case control study. Br J Cancer 86: 350–355

Linet MS, Wacholder S, Zahm SH (2003) Interpreting epidemiologic research: lessons from childhood cancer. Pediatrics 112: 218–232

Little J (1999) Epidemiology of Childhood Cancer. IARC Scientific publication, no. 149

Mathur GP, Gupta N, Mathur S, Gupta V, Pradhan S, Dwivedi JN, Tripathi BN, Kushwaha KP, Sathy N, Modi UJ (1993) Indian Pediatrics 30 (5): 651–657

McNally RJ, Cairns DP, Eden OB, Alexander FE, Taylor GM, Kelsey AM, Birch JM (2002) An infectious aetiology for childhood brain tumours? Evidence from space–time clustering and seasonality analyses. Br J Cancer 86: 1070–1077

McNally RJQ, Alston RD, Eden TOB, Kelsey AM, Birch JM (2004) Further clues concerning the aetiology of childhood central nervous system tumours. Eur J Cancer 40 (18): 2766–2772

McNally RJQ, Eden TOB (2004) An infectious aetiology for childhood acute leukaemia: a review of the evidence. Br J Haematol 127 (3): 243–263

Nyari TA, Dickinson HO, Hammal DM, Parker L (2003) Childhood solid tumours in relation to population mixing around the time of birth. Br J Cancer 88: 1370–1374

Rosenbaum PF, Buck GM, Brecher ML (2000) Early child-care and preschool experiences and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Epidemiol 152: 1136–1144

Rothman KJ (1998) Chapter 8, Modern Epidemiology. Sander Greenland

Schuz J, Kaletsch U, Kaatsch P, Meinert R, Michaelis J (2001) Risk factors for pediatric tumours of the central nervous system: results from a German population-based case–control study. Med Pediatr Oncol 36: 274–282

Shaw AK, Li P, Infante-Rivard C (2006) Early infection and risk of childhood brain tumors (Canada). Cancer Causes Control 17: 1267–1274

Shu XO, Linet MS, Steinbuch M, Wen WQ, Buckley JD, Neglia JP, Potter JD, Reaman GH, Robison LL (1999) Breast-feeding and risk of childhood acute leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 1765–1772

Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A (1988) Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. London: Croom Helm

UKCCS Investigators (2000) The United Kingdom childhood cancer study: objectives, materials and methods. Br J Cancer 82: 1073–1102

WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality (2000) Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet 355: 451–455

Wright CM, Parkinson K, Scott J (2005) Breast-feeding in a UK urban context: who breast-feeds, for how long and does it matter? Public Health Nutr 9 (6): 686–691

Acknowledgements

The UKCCS was sponsored and administered by the United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research and was supported by the Childhood Cancer and Leukaemia Group (formerly UKCCSG) paediatric oncologists and by the National Radiological Protection Board. Financial support was provided by: Cancer Research UK, Leukaemia Research Fund, and Medical Research Council through grants to their units; Leukaemia Research Fund for the UKCCS data centre at the University of York; Leukaemia Research Fund, Department of Health, member companies of Electricity Association, Irish Electricity Supply Board, National Grid Company plc, and Westlakes Research (Trading) Ltd for general expenses of the study; Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund for associated laboratories studies; and Foundation of Children with Leukaemia for study of electrical fields. The investigation in Scotland was funded by the Scottish Office, Scottish Power plc, Scottish Hydro-electric plc, and Scottish Nuclear Ltd. We thank the members of the UKCCSG for their support, the staff of the local hospitals, the family physicians and their practice staff. We especially thank the families of the children included in the study for their help. The analyses for this paper were supported by Cancer Research UK. JM Birch is a Cancer Research UK Professorial Fellow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Harding, N., Birch, J., Hepworth, S. et al. Breastfeeding and risk of childhood CNS tumours. Br J Cancer 96, 815–817 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603638

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603638

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Breastfeeding and risk of childhood brain tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer and Leukemia International Consortium

Cancer Causes & Control (2023)

-

Association between maternal breastfeeding and risk of systemic neoplasms of offspring

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2022)

-

UK case control study of brain tumours in children, teenagers and young adults: a pilot study

BMC Research Notes (2014)

-

Infectious exposure in the first year of life and risk of central nervous system tumors in children: analysis of day care, social contact, and overcrowding

Cancer Causes & Control (2009)