Abstract

Long-term cancer survivors risk development of second primary cancers (SPC). Vigilant follow-up may be required. We report outcomes of 92 patients who underwent chemoradiation for unresectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer, with a median follow-up of 8.9 years. The incidence of SPC was 2.4 per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval: 1.0–4.9).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Second primary cancer (SPC) and secondary leukaemia have been recognised in survivors of non-metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Duchateau and Stokkel, 2005). In one study in which, 547 patients were treated with chemoradiation (CRT) using a variety of chemotherapeutic regimens, radiation (RT) doses, and schedules (Kawaguchi et al, 2006). Sixty-two patients were disease free more than 3 years, but nine of them developed SPC with an incidence estimated at 2.9 per 100 patient-years. Furthermore, the causes of death in long-term survivors of advanced NSCLC have not been fully described. More data are required to understand the risk of SPC and to establish guidelines for follow-up after combined modality treatment.

We previously reported the 2- or 3-year survival outcomes of two concurrent CRT regimens in surgically unresectable stage III NSCLC (Segawa et al, 2000; Kiura et al, 2003). Here we report long-term results on cause of death and analysis of SPC in these two trials with a minimum follow-up period of 5 years.

Patients and methods

Patients

Between January 1994 and December 1999, two phase II concurrent CRT studies for locally advanced unresectable stage IIIA and IIIB NSCLC in a total of 92 patients were conducted. Briefly, patients had histologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC, previously untreated disease, measurable lesions, age ⩽75 years, and no history of malignancy within 5 years of enrollment. Any patients who had previously undergone chemotherapy or radiotherapy were excluded. Institutional review boards approved study protocols, and patients provided written informed consent. Treatment in one study consisted of three cycles of 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2, days 1–5) and cisplatin (FP-RT) (20 mg/m2, days 1–5), every 4 weeks, and concurrent hyperfractionated RT (1.25 Gy twice daily, total dose: 62.5–70 Gy) (FP-RT). In the second study, treatment consisted of combination docetaxel 40 mg/m2 and cisplatin (DP-RT) 40 mg/m2, days 1, 8, 29, and 36 with concurrent RT (2 Gy daily, total 60 Gy) (DP-RT). For the first 2 years following therapy, patients were monitored monthly with chest radiography and every 6 months with computed tomography (CT) (chest and abdomen) and magnetic resonance imaging (brain). After 2 years, chest radiography was performed annually whereas annual brain MRI and semi-annual CT continued. SPC in the lung was defined according to the methods of Martini and Melamed (1975). Patients’ status was described according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program version 11.0J (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Survival time was defined as the period from CRT treatment initiation to last follow-up evaluation or death. SPC rate was calculated as the ratio of SPC cases over 100 patient-years of follow-up (Thomas and Rubinstein, 1993; Jeremic et al, 2001).

The interval of initial NSCLC to SPC was measured from the initiation of CRT to SPC diagnosis, where the date of first clinical evidence of histologically or cytologically confirmed SPC was used. Survival rates and cumulative risks of developing SPC were calculated using Kaplan and Meier method and differences in survival distribution between two categorised groups were assessed using a log-rank test. P-values less than 0.05 in two-tailed analyses were considered significant. Analyses of these data are based on information available as of 1 October 2005. Data for patients still alive at last follow-up or dead without developing SPC were censored when calculating the cumulative risks.

Results

In the first study, 50 patients were treated with FP-RT and in the second study 42 patients were treated with DP-RT. Among these 92 patients were 81 men and 11 women. At treatment initiation, 21 patients had stage IIIA and 71 patients had stage IIIB disease. The median age for all patients was 65 years (range; 29–75 years). Performance status was 0 (n=35), one (n=54) and two (n=3). With a median follow-up time of 8.9 years (range, 5.2–11.4 years), the observed 5-year survival rate was 30%, with 28 of 92 patients surviving more than 5 years. Median survival time was 2.0 years (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–2.5 years) (Figure 1). In the FP-RT study the 5-year survival rate was 30% and in the DP-RT study it was 31%. The median survival times were 1.6 years (95% CI: 0.91–2.25 years) and 2.1 years (95% CI: 0.82–2.5 years), respectively.

Among the 92 patients, two did not complete the originally planned treatment. One had a treatment-related death and another developed cerebral infarction; they were therefore not included in this analysis. Of the remaining 90 patients, 61 (68%) eventually developed disease progression. The most common site of initial failure was within the site of original disease (local progression only, n=28; local plus distant progression, n=8; distant progression only n=24; unspecified, n=1). Brain metastases were observed in eight patients, and for six it was the only site of relapse. Among the 28 patients who survived more than 5 years, four died owing to progression of primary NSCLC, three died owing to SPC, two were lost to follow-up, and 19 were alive. Four of the 19 long-term survivors developed SPC (two NSCLC, one small-cell lung cancer, and one oesophageal cancer). Thus, from 90 patients initially included in the two studies a total of seven (7.8%) developed SPC (two NSCLC, one small-cell lung cancer, two oesophageal cancer, and two biliary tract cancer) (Table 1). No patients developed leukaemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. The two patients with second NSCLC (both stage IA) underwent surgery, whereas the patient with small-cell lung cancer (limited disease) received chemotherapy. All were alive at the time of data cutoff. In the two patients with oesophageal cancer, one was alive and the other had died at the time of data cutoff. The former had cancer detected by routine endoscopy, in the absence of symptoms; the latter was diagnosed with advanced disease after developing dysphagia. The patient with gall bladder cancer reported abdominal pain, but despite surgery with curative intent, died of SPC. The patient with bile duct cancer presented with jaundice, received palliative chemotherapy, and died of SPC. All patients who developed SPC had a history of smoking, but only one continued after the diagnosis of primary NSCLC was made. Only one SPC arose in the RT treatment of initial NSCLC.

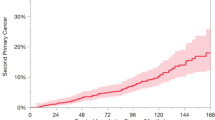

The observed incidence rate of SPC was 2.4 per 100 patient-years (95% CI: 1.0–4.9). Cumulative incidence was 2.7% (standard error s.e. 2.6%) at 3 years, 5.8 % (s.e. 4.0%) at 5 years, 10.0% (s.e. 5.6%) at 8 years, 41.8% (s.e. 15.3%) at 9 years, and 60.8% (s.e. 18.9%) at 10 years (Figure 2). The median time from the beginning of CRT to the diagnosis of SPC was 9.6 years (95% CI: 8.1–11.1 years). All patients with SPC showed no progressive disease of the primary NSCLC.

Discussion

The analysis of data after a median 8.9 years demonstrates that for patients treated with CRT for unresectable NSCLC in our previous studies, the 5-year-survival rate was 30%. In the patients who underwent rigorous follow-up detection of SPC was assured. Three primary lung cancers were detected during routine follow-up and were curatively treated. Routine follow-up in this study seemed useful to identify early stage lung cancer, however, additional examinations such as ultrasonic abdominal imaging, occult blood stool tests, endoscopy, or measurement of tumour markers may also be beneficial for early detection of alimentary canal cancer in such patients with high-risk of SPC. Further investigation of follow-up methods including cost-benefit analysis is necessary.

The studies using the person-years method to calculate the incidences of SPC showed a range from 1.7 to 4.3 per 100 patient-years (Thomas and Rubinstein, 1993; Ginsberg and Rubinstein, 1995; Martini et al, 1995; Jeremic et al, 2001; Kawaguchi et al, 2006). In the present studies, the rate of SPC was 2.4 per 100 patient-years, in agreement with previous findings. Chemotherapy and RT may be carcinogenic treatments and may have contributed to SPC compared with surgery for early NSCLC (Allan and Travis, 2005). Patients with locally advanced NSCLC still have poor prognosis. Concurrent platin-containing CRT prolongs survival (Aupérin et al, 2006), despite the increased risk of SPC in long-term survivors. In this study, it is difficult to speculate on the association of SPC with RT because only one SPC was present in the RT field.

Despite the small sample size in these studies, a significant number of patients treated with concurrent CRT for locally advanced unresectable stage IIIA and IIIB NSCLC survived more than 5 years. Brain metastases in long-term NSCLC survivors have been widely reported and have been the focus of several studies (Carolan et al, 2005; Gaspar et al, 2005). As we observed that SPC occurs just as frequently, long-term survivors require vigilant follow-up to detect SPC at the earliest possible stage. Studies to find methods to prevent SPC in such patients are warranted.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allan JM, Travis LB (2005) Mechanisms of therapy-related carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 943–955

Aupérin A, Le Pechoux C, Pignon JP, Koning C, Jeremic B, Clamon G, Einhorn L, Ball D, Trovo MG, Groen HJ, Bonner JA, Le Chevalier T, Arriagada R (2006) Concomitant radio-chemotherapy based on platin compounds in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a meta-analysis of individual data from 1764 patients. Ann Oncol 17: 473–483

Carolan H, Sun AY, Bezjak A, Yi QL, Payne D, Kane G, Waldron J, Leighl N, Feld R, Burkes R, Keshavjee S, Shepherd F (2005) Does the incidence and outcome of brain metastases in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer justify prophylactic cranial irradiation or early detection? Lung Cancer 49: 109–115

Duchateau CS, Stokkel MP (2005) Second primary tumors involving non-small cell lung cancer: prevalence and its influence on survival. Chest 127: 1152–1158

Gaspar LE, Chansky K, Albain KS, Vallieres E, Rusch V, Crowley JJ, Livingston RB, Gandara DR (2005) Time from treatment to subsequent diagnosis of brain metastases in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective review by the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 23: 2955–2961

Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV (1995) Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 60: 615–622, discussion 622–623

Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Acimovic L, Nikolic N, Dagovic A, Aleksandrovic J, Radosavljevic-Asic G (2001) Second cancers occurring in patients with early stage non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chest radiation therapy alone. J Clin Oncol 19: 1056–1063

Kawaguchi T, Matsumura A, Iuchi K, Ishikawa S, Maeda H, Fukai S, Komatsu H, Kawahara M (2006) Second primary cancers in patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer successfully treated with chemo-radiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol 36: 7–11

Kiura K, Ueoka H, Segawa Y, Tabata M, Kamei H, Takigawa N, Hiraki S, Watanabe Y, Bessho A, Eguchi K, Okimoto N, Harita S, Takemoto M, Hiraki Y, Harada M, Tanimoto M (2003) Phase I/II study of docetaxel and cisplatin with concurrent thoracic radiation therapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 89: 795–802

Martini N, Bains MS, Burt ME, Zakowski MF, McCormack P, Rusch VW, Ginsberg RJ (1995) Incidence of local recurrence and second primary tumors in resected stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 109: 120–129

Martini N, Melamed MR (1975) Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 70: 606–612

Segawa Y, Ueoka H, Kiura K, Kamei H, Tabata M, Sakae K, Hiraki Y, Kawahara S, Eguchi K, Hiraki S, Harada M (2000) A phase II study of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with concurrent hyperfractionated thoracic radiation for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a preliminary report from the Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer 82: 104–111

Thomas Jr PA, Rubinstein L (1993) Malignant disease appearing late after operation for T1 N0 non-small-cell lung cancer. The Lung Cancer Study Group. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 106: 1053–1058

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Naokatsu Horita (Kure Kyosai Hospital), Naoyuki Nogami (Shikoku Cancer Center), Keisuke Matsuo (Okayama Red Cross Hospital), Tadashi Maeda, Keisuke Aoe (National Sanyo Hospital), Katsuyuki Hotta, Akiko Hisamoto (Okayama University Hospital), Ichiro Takata (Fukuyama Medical Center), Keiichi Fujiwara (Okayama Medical Center), and Shingo Harita and Shoichi Kuyama (Chugoku Central Hospital) for their collaboration. We also thank Drs Takashi Shimamoto, Karla MacKenzie, and Steven Olsen for reviewing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Takigawa, N., Kiura, K., Segawa, Y. et al. Second primary cancer in survivors following concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 95, 1142–1144 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603422

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603422

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence of lung tumors in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and vice versa: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

The effect of consolidation chemotherapy after concurrent chemoradiotherapy on the survival of patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2017)