Abstract

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study among 179 398 Swedish patients hospitalised for alcoholism from 1970 to 1994, and found no excess risk for colorectal cancers, overall or at any anatomical subsite. Our findings challenge the hypothesis that alcohol intake is a risk factor for cancer of the large bowel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

A role of alcohol in the aetiology of colorectal cancer has long been suspected. However, epidemiological data, as summarised in two reviews (Kune and Vitetta, 1992; Potter, 1999), are conflicting, both with regard to the existence of such an association and to possible variations by anatomical subsites. The disagreement continues in subsequent studies (Gerhardsson de Verdier et al, 1993; Goldbohm et al, 1994; Glynn et al, 1996b; Le Marchand et al, 1997; Hsing et al, 1998; Munoz et al, 1998; Tavani et al, 1998; Nagata et al, 1999; Sharpe et al, 2002). For experimental colon cancer, the tumorigenesis in the right and left colon was affected differently by the level of alcohol consumed (Seitz et al, 1998).

If alcohol is indeed a risk factor for colorectal cancer, this association should be easiest to document among subjects with a high and long-term intake, such as alcoholics. However, previous studies of alcoholics have not been large enough to generate stable relative risk estimates by subsite. Moreover, the follow-up time has generally been short or incomplete (Hakulinen et al, 1974; Monson and Lyon, 1975; Robinette et al, 1979; Schmidt and Popham, 1981; Adami et al, 1992; Tonnesen et al, 1994; Sigvardsson et al, 1996) We therefore conducted a large nationwide retrospective cohort study, based on the Swedish Inpatient Register, to quantify the risk of colorectal cancer among patients hospitalised at least once with a diagnosis of alcoholism.

Patients and methods

This record-linkage study was based on the Swedish Inpatient Register created by the National Board of Health and Welfare and described in detail elsewhere (Nyren et al, 1995). In brief, the register contains administrative and medical data such as hospital department and discharge diagnoses. Ascertainment of cancer incidence was achieved by linkage to the more than 98% complete Swedish Cancer Register, which used the ICD-7 classification throughout the study period. As a separate code for cancer of the anus (ICD7 code 154.1) was first introduced in 1970, our study period began in 1970, rather than 1965 when the Inpatient Register was started.

We identified 193 040 discharge records in the Inpatient Register with a diagnosis of alcoholism (ICD-8=291, 303; ICD-9=291, 303, 305A) during 1970–1994. Record linkage to the nationwide Register of Causes of Death allowed us to identify deaths among the study cohort through 1995. Corresponding linkage to the Emigration Register identified dates of emigration. To remove records with incorrect national registration numbers, which would otherwise contribute person-years at no risk of cancer, we also linked the cohort file to the Register of the Total Population. If a national registration number could not be traced in this register, or in the reports of death and emigration, it was deemed to be of erroneous or incomplete numbers and thus excluded (7425 records). We also excluded 3348 patients with prevalent cancers, since our analysis concerns first primary cancer only. We further excluded 2136 patients who died during the hospitalisation for alcoholism and 733 patients with inconsistencies uncovered during record linkage. Thus, a total of 179 398 patients, 36 568 women and 142 830 men, were entered into the study cohort.

Since the likelihood of being hospitalised for alcoholism may increase if there are also insidious symptoms of a yet undetected cancer, we excluded the first year of follow-up in our study. Thus, follow-up time (person-years) was calculated 1 year after the first recorded (index) hospitalisation for alcoholism until the occurrence of a first cancer diagnosis, emigration, death, or the end of the observation period (31 December 1995), whichever occurred first. To avoid possible ascertainment bias caused by differential autopsy rates, we did not count cancers found incidentally at autopsy. The expected number of cancers was calculated by multiplying the observed number of person-years in age- (in 5-year groups), gender-, and calendar-year-specific strata by the corresponding cancer incidence rates, derived from the entire Swedish population (Ye et al, 2001). Relative risk was estimated as the standardised incidence ratio (SIR), defined as the ratio of the observed number of cancers to that expected. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the SIR was calculated on the assumption that the observed number follows a Poisson distribution (Bailar and Ederer, 1964).

No information was available on severity or duration of alcoholism, nor on treatment given. However, we had information on accompanying codiagnoses at the index or subsequent admissions. Stratified analyses were performed on the presence or absence of liver cirrhosis. Person-years before the first recorded occurrence of an accompanying disease were allocated to the comorbidity-negative strata. We also stratified the analyses by selected cohort characteristics that may influence the results, including gender and follow-up duration.

Results

The mean age at index hospitalisation among the 179 398 alcoholics (36 568 women, 142 830 men) was 45 years, and the mean duration of follow-up was around 9 years, yielding a total of 1 627 902 person-years at risk (Table 1). Of these patients, 7236 (4.0%) had a codiagnosis of liver cirrhosis at least once during the period up to 1 year before the end of observation.

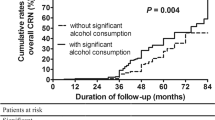

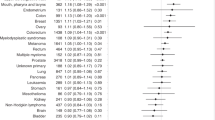

Based on a total of 929 incident cancers of the colon or rectum vs 931 expected, we did not observe any significant overall excess risk of colorectal cancer during 1–25 years of observation (SIR=1.00, 95% CI, 0.93–1.06) (Table 2). When examined by separate subsites, a lack of association was evident for colon (SIR=1.00), right-sided colon (SIR=0.97), left-sided colon (SIR=0.96), and for rectal cancer (SIR=0.99). Further stratification by gender, follow-up duration and presence of liver cirrhosis did not reveal any significant excess risk of colorectal cancer, overall or at any anatomical subsite.

Discussion

This is the largest cohort study to date on risk of colorectal cancer among alcoholics. It enabled detailed analyses by anatomic subsites. This study design offers a number of strengths, including the reduction in potential recall bias. Further, the high quality of Swedish national registers and the consistent use of the unique national registration numbers assigned to each person ensure correct linkage, thereby precluding selective loss to follow-up. One potential concern is the possibility of biased ascertainment or detection of the cancer outcome. A lower diagnostic coverage among alcoholics than in the population at large would entail underestimation of the true relative risk. However, the Swedish health-care system, with low patient fees and equal access to hospital care for everyone, helps allay this concern. Had underascertainment of cancer morbidity been a general problem, we would expect the overall cancer incidence to be low, but this was not the case (data not shown).

Another concern is the lack of information about amount and type of alcohol intake, duration of alcohol abuse before index hospitalisation, and treatment. It precludes a meaningful assessment of dose–response relation, but it is unlikely to affect seriously the overall association with colorectal cancer risk. Imperfect specificity of the alcoholism diagnosis (a high false-positive rate) could conceivably bias a true positive association towards the null. However, the threshold for making an in-hospital diagnosis of alcoholism is generally high. Patients registered with this diagnosis in their case records mostly have a clearly manifested disease. Therefore, the rate of false-positive alcoholism diagnoses in the Swedish Inpatient Register is deemed to be low. A high prevalence of alcoholism in the reference population might be yet another source for underestimation of a true-positive association with colorectal cancer risk. Admittedly, approximately up to 10% of the Swedish adult population is estimated to have problems with alcohol overconsumption (Mutzell et al, 1987; Spak and Hallstrom, 1995), but the per capita consumption in Sweden is lower than in most European and American countries (Ramstedt, 2001).

Our most serious concern is the absence of information about cofactors possibly related both to alcoholism and to the cancer outcome. Confounding from such cofactors, for example, smoking (Giovannucci, 2001), low intake of vegetables and fruits (Potter, 1996), folate deficiency (Giovannucci et al, 1995b; Glynn et al, 1996a; Su and Arab, 2001), and physical activity (Giovannucci et al, 1995a), however, would rather tend to inflate the relative risk estimates. We have been unable to identify any factor – except possibly for use of aspirin that is conceivably high among alcoholics and might protect from colon cancer (Thun et al, 1991) – that has the potential of introducing negative confounding. We therefore conclude that our negative findings are unlikely to be explained by bias or confounding.

In conclusion, our findings did not support an important role of alcohol in the aetiology of colorectal cancer.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Adami HO, McLaughlin JK, Hsing AW, Wolk A, Ekbom A, Holmberg L, Persson I (1992) Alcoholism and cancer risk: a population-based cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 3: 419–425

Bailar JC, Ederer F (1964) Significance factors for the ratio of a Poisson variable to its expectation. Biometrics 20: 639–643

Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Romelsjo A, Lundberg M (1993) Alcohol and cancer of the colon and rectum. Eur J Cancer Prev 2: 401–408

Giovannucci E (2001) An updated review of the epidemiological evidence that cigarette smoking increases risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10: 725–731

Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (1995a) Physical activity, obesity, and risk for colon cancer and adenoma in men. Ann Intern Med 122: 327–334

Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC (1995b) Alcohol, low-methionine--low-folate diets, and risk of colon cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 265–273

Glynn SA, Albanes D, Pietinen P, Brown CC, Rautalahti M, Tangrea JA, Gunter EW, Barrett MJ, Virtamo J, Taylor PR (1996a) Colorectal cancer and folate status: a nested case–control study among male smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 5: 487–494

Glynn SA, Albanes D, Pietinen P, Brown CC, Rautalahti M, Tangrea JA, Taylor PR, Virtamo J (1996b) Alcohol consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in a cohort of Finnish men. Cancer Causes Control 7: 214–223

Goldbohm RA, Van den Brandt PA, Van 't Veer P, Dorant E, Sturmans F, Hermus RJ (1994) Prospective study on alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer of the colon and rectum in the Netherlands. Cancer Causes Control 5: 95–104

Hakulinen T, Lehtimaki L, Lehtonen M, Teppo L (1974) Cancer morbidity among two male cohorts with increased alcohol consumption in Finland. J Natl Cancer Inst 52: 1711–1714

Hsing AW, McLaughlin JK, Chow WH, Schuman LM, Co Chien HT, Gridley G, Bjelke E, Wacholder S, Blot WJ (1998) Risk factors for colorectal cancer in a prospective study among U.S. white men. Int J Cancer 77: 549–553

Kune GA, Vitetta L (1992) Alcohol consumption and the etiology of colorectal cancer: a review of the scientific evidence from 1957 to 1991. Nutr Cancer 18: 97–111

Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Hankin JH, Lyu LC (1997) Associations of sedentary lifestyle, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and diabetes with the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 57: 4787–4794

Monson RR, Lyon JL (1975) Proportional mortality among alcoholics. Cancer 36: 1077–1079

Munoz SE, Navarro A, Lantieri MJ, Fabro ME, Peyrano MG, Ferraroni M, Decarli A, La Vecchia C, Eynard AR (1998) Alcohol, methylxanthine-containing beverages, and colorectal cancer in Cordoba, Argentina. Eur J Cancer Prev 7: 207–213

Mutzell S, Tibblin G, Bergman H (1987) Heavy alcohol drinking and related symptoms in a population study of urban men. Alcohol Alcohol 22: 419–426

Nagata C, Shimizu H, Kametani M, Takeyama N, Ohnuma T, Matsushita S (1999) Cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and colorectal adenoma in Japanese men and women. Dis Colon Rectum 42: 337–342

Nyren O, McLaughlin JK, Gridley G, Ekbom A, Johnell O, Fraumeni Jr JF, Adami HO (1995) Cancer risk after hip replacement with metal implants: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 28–33

Potter JD (1996) Nutrition and colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 7: 127–146

Potter JD (1999) Colorectal cancer: molecules and populations. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 916–932

Ramstedt M (2001) Per capita alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis mortality in 14 European countries. Addiction 96(Suppl 1): S19–S33

Robinette CD, Hrubec Z, Fraumeni Jr JF, (1979) Chronic alcoholism and subsequent mortality in World War II veterans. Am J Epidemiol 109: 687–700

Schmidt W, Popham RE (1981) The role of drinking and smoking in mortality from cancer and other causes in male alcoholics. Cancer 47: 1031–1041

Seitz HK, Poschl G, Simanowski UA (1998) Alcohol and cancer. Recent Dev Alcohol 14: 67–95

Sharpe CR, Siemiatycki J, Rachet B (2002) Effects of alcohol consumption on the risk of colorectal cancer among men by anatomical subsite (Canada). Cancer Causes Control 13: 483–491

Sigvardsson S, Hardell L, Przybeck TR, Cloninger R (1996) Increased cancer risk among Swedish female alcoholics. Epidemiology 7: 140–143

Spak F, Hallstrom T (1995) Prevalence of female alcohol dependence and abuse in Sweden. Addiction 90: 1077–1088

Su LJ, Arab L (2001) Nutritional status of folate and colon cancer risk: evidence from NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Ann Epidemiol 11: 65–72

Tavani A, Ferraroni M, Mezzetti M, Franceschi S, Lo Re A, La Vecchia C (1998) Alcohol intake and risk of cancers of the colon and rectum. Nutr Cancer 30: 213–219

Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Heath Jr CW (1991) Aspirin use and reduced risk of fatal colon cancer. N Engl J Med 325: 1593–1596

Tonnesen H, Moller H, Andersen JR, Jensen E, Juel K (1994) Cancer morbidity in alcohol abusers. Br J Cancer 69: 327–332

Ye W, Chow WH, Lagergren J, Yin L, Nyren O (2001) Risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia in patients with gastroesophageal reflux diseases and after antireflux surgery. Gastroenterology 121: 1286–1293

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by several grants from Swedish Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, W., Romelsjö, A., Augustsson, K. et al. No excess risk of colorectal cancer among alcoholics followed for up to 25 years. Br J Cancer 88, 1044–1046 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600846

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600846