Abstract

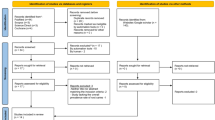

Data sources

Seven electronic databases including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane Library, LILACS and ClinicalTrials.gov and grey literature were searched. There was no information regarding the restriction of language or publication date.

Study selection

Four reviewers included both epidemiological and experimental clinical studies that investigated the presence of oral C. albicans in children (age < 6 years), with or without ECC. Studies including children with severe systematic diseases were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were abstracted independently by four reviewers. Risk of bias was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Meta-analysis was performed. The overall odds ratio of associations between the presence of C. albicans and ECC was calculated. Subgroup analysis on the different sample collection sites (plaque, swab and saliva) was performed.

Results

Fifteen cross-sectional studies were included for the qualitative assessment and nine studies for meta-analysis. Regarding the quality assessment, all included studies were rated as ‘fair’ or ‘good’. Children with the presence of oral C. albicans had 6.51 times as likely, to have ECC experience, compared to those without C. albicans (95% CI: 4.948.57, p<0.01). The odds of experiencing ECC in children with C. albicans versus those without C. albicans were 6.69 for plaque, 6.3 for oral swab, and 5.26 for salivary samples.

Conclusions

Children with oral C. albicans have higher odds of experiencing ECC, compared to children without C. albicans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Early childhood caries (ECC) is the most common childhood oral disease that affects young children worldwide, particularly in disadvantaged communities or developing countries.1 The aetiology of ECC has been related to multi-species bacterial infection. Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus species are commonly studied in the literature. In recent years, microbiological data have revealed that fungal organisms were also associated with dental caries in childhood. In particular, Candida albicans was frequently detected at higher levels in children with severe ECC, compared with children without ECC.2 However, no positive correlation was found between ECC experience and C. albicans, while implying it may be regarded as a cornerstone commensal organism.3 The role of Candida in the pathogenesis of ECC remains ambiguous.4

The authors of the present study endeavoured to evaluate the association between oral C. albicans and caries experience in young children through a meta-analysis and systematic review. An extensive database search was conducted by four reviewers. Restriction on language or publication date were not clearly stated. Almost all of the included studies were published in English, except one in Chinese. The publication year of the included studies ranged from 2000 to 2016. After retrieving the full texts, reasons for exclusions were not clearly described. There was no restriction on study designs (including all experimental and epidemiological studies), nevertheless, there were no cohort or randomised clinical studies found, with only cross-sectional studies included. Quality assessment of the studies was carried out and none of them was graded as ‘low’ quality.

Although the magnitude of pooled odds ratio estimates highly supported the relationship of the presence of C. albicans and caries experience, potential biases may have occurred. The authors recognised the study limitations due to the types of studies included and small sample size of most studies. Another concern was the heterogeneity of the study designs regarding the different sample collection sources, various types of fungal identifications and caries diagnostic criteria. However, the generalisability or external validity was not mentioned. Since the majority of the included studies recruited their participants from clinics or unspecified places, there is uncertainty if these groups would be representative of the general child population. Publication bias, in which positive findings have a higher chance of being published in the early stages of discovery, may be also a threat, possibly leading to invalid conclusions. Registered prospective studies may be helpful to prevent biases associated with nonpublication.

Despite a strong association between C. albicans and ECC, these results should be interpreted with caution, as the quality of the available evidence is likely to be low due to the high risk of biases derived from the cross-sectional studies. A statistical association does not mean that one variable inevitably causes the other. Nevertheless, this summary paper provides insightful information regarding the potential role of C. albicans in ECC development, and enhances interest among paediatric dentists and general practitioners. In summary, there is limited evidence that the presence of oral C. albicans is significantly associated with ECC. Prospective cohort studies are needed to clarify whether C. albicans is a causative factor of dental caries in young children or in other age groups of populations. The complex fungal-bacterial ecology and host response mechanisms during the caries process should be further studied.

References

Duangthip D, Gao SS, Lo EC, Chu CH . Early childhood caries among 5- to 6-year-old children in Southeast Asia. Int Dent J 2017; 67:98–106.

Xiao J, Moon Y, Li L, et al. Candida albicans carriage in children with severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) and maternal relatedness. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0164242.

Janus MM, Willems HM, Krom BP . Candida albicans in multispecies oral communities: a keystone commensal? Adv Exp Med Biol 2016; 931:13–20.

Neves AB, Lobo LA . Pinto KC et al. Comparison between clinical aspects and salivary microbial profile of children with and without early childhood caries: A Preliminary Study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2015; 39:209–214.

Duangthip D, Gao SS, Lo EC, Chu CH . Early childhood caries among 5- to 6-year-old children in Southeast Asia. Int Dent J 2017; 67:98–106.

Xiao J, Moon Y . Li L et al. Candida albicans carriage in children with severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) and maternal relatedness. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0164242.

Janus MM, Willems HM, Krom BP . Candida albicans in multispecies oral communities: a keystone commensal? Adv Exp Med Biol 2016; 931:13–20.

Neves AB, Lobo LA . Pinto KC et al. Comparison between clinical aspects and salivary microbial profile of children with and without early childhood caries: A Preliminary Study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2015; 39:209–214.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Jin Xiao, 625 Elmwood Ave. Rochester, NY 14618 (USA). E-Mail: jin_xiao@urmc.rochester.edu

Xiao J, Huang X, Alkhers N et al. Candida albicans and early childhood caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Caries Res 2018; 52: 102-112.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D, D. Early childhood caries and candida albicans. Evid Based Dent 19, 100–101 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401337

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401337