Abstract

Data sources

Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and SIGLE.

Study selection

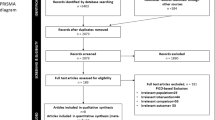

Randomised controlled trials(RCTs), clinical controlled trials (CCTs) and cohort studies that assessed the success/failure rates of self-drilling and self-tapping mini-screws for orthodontic anchorage were considered.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data was abstracted and assessed for quality by two reviewers independently. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the methodological quality. Meta-analyses with subgroup analysis of different study designs, follow-up periods, participant age and immediate loading or delayed loading were conducted.

Results

Three CCTs and three cohort studies were included. These were assessed to be of high quality. Meta-analysis (six studies) showed no difference in success rates between the two types of screws; odds ratio (OR) = 0.90 (95%CI; 0.52-1.53). Meta-analysis (two studies) found no difference in the rate of root contact between the two systems; OR = 0.96 (95% CI; 0.53-1.71).

Conclusions

Currently available clinical evidence suggests that the success rates of self-tapping and self-drilling miniscrews are similar. Determination of the position and direction of placement should be more precise when self-drilling miniscrews are used in sites with narrow root proximity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

For the primary research question of the systematic review by Yi et al.1 that was appraised in this commentary, the authors assessed the differences in success rates between self-drilling and self-tapping (pre-drilling) orthodontic mini-implants. For the secondary question they assessed differences in the rates of implant-root contact between these insertion methods in the studies that were found eligible for the first research question. In appraising this review we (RMR, GC) independently scored the methodological validity and risk of bias for the primary research question with respectively the AMSTAR2,3 and ROBIS tools.4,5

Complete agreement on the AMSTAR and ROBIS scores was reached through discussions. We summarised these outcomes in Tables 1 and 2 and presented the rationale for these scores in the section ‘Limitations of this systematic review’.

Limitations of the systematic review

When defining primary outcomes, the authors of this systematic review focused on the success rates of two different interventions for inserting orthodontic mini-implants, but they should also have included at least one adverse effect of these interventions as a primary outcome.6 This is mandatory for research questions of Cochrane systematic reviews7 and is an important issue, because implants could for example damage, ie penetrate, dental roots during the insertion process and this damage might differ between the two insertion techniques.8

The authors did not register or publish their protocol in PROSPERO9 or in open access institutional repositories10-12 or at The Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization.13 Not publishing or registering review protocols is a serious problem, because it could introduce bias in the selection of the reported results.14 The absence of a protocol also made it impossible to verify various items that were under-reported or missing.15

The eligibility criteria were not described in sufficient detail. It was also unclear whether these criteria were specified in a protocol or adopted post-hoc. Specified time-points for measuring outcomes were not defined. This is an important eligibility criterion because short-term implant success, eg, as less than 120 days of force application is not clinically relevant, because most orthodontic objectives cannot be completed in such short time -frames. Eligible definitions of success/failure of orthodontic mini-implants were also not presented, and references of excluded studies were not given.

The authors scored all six eligible studies as ‘high quality’ using the Newcastle Ottawa scale,16 but did not consider the shortcomings of this scale. These limitations refer to: (1) a summary quality score of ‘high quality’ was assigned to a study when five or more of nine quality items were scored as ‘high quality’. However, scoring overall value judgments should be discouraged, because certain limitations could be more critical than others and they could vary for different settings.17 For example, two studies scored a five and one a six for the nine quality items of the NOS. Patient selection, confounding, blinding, selective reporting and lost to follow-up was either not controlled or reported in some or all of the selected studies and could be critical measures for the summary quality score; (2) the NOS has important limitations such as an insufficient guidance on how to use this instrument,18 as was evidenced in a variety of research studies that found low reliability between reviewers that used this scale.19,20,21 The Risk of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions ROBINS-I tool22 developed by the Cochrane Collaboration and formerly known as the ACROBAT-NRSI tool23 would have been our preferred instrument for assessing the validity of the non-randomised eligible studies in this systematic review.

The authors summarised the primary effect sizes from the six eligible studies in a meta-analysis. We judged that conducting a meta-analysis was not appropriate in this systematic review because of the various bias issues, but above all because different outcome measures were synthesised. For example, the time points of measuring implant success varied significantly between eligible studies, were too short in several studies (1, 2, or 6 weeks after implant insertion) or were not specified at all. The authors should have aimed a priori for one of 2 options: (1) apply broad-spectrum eligibility criteria, present the different effect sizes in a forest plot to display the dispersion of outcomes, and not undertake a meta-analysis (Fig. 1);24 or (2) apply narrow-spectrum eligibility criteria for a well-defined time period for measuring outcomes, eg, six months after orthodontic force application, and conduct a meta-analysis when additional criteria (such as low risk of bias) for undertaking such an analysis are met.25,26

Some important shortcomings in using and interpreting the statistics were also identified: (1) the authors planned to undertake a meta-analysis with a random-effects model when the ratio of true heterogeneity to total heterogeneity (I2) was moderate (25%<I2<50%) or high (I2>50%). However, they did not adhere to this plan, because they calculated an I2 of 41% and conducted a fixed effect model meta-analysis instead; (2) this choice is further problematic, because the choice between using a fixed-effect or random-effects model should not be based on the statistical test for heterogeneity. Actually the random-effects model should have been the logical starting point, because it is not realistic to assume that the true effect size would be the same for all eligible studies in this review;2; and (3) The authors of this systematic review self-defined specific thresholds for classifying moderate and high heterogeneity. However, the statisticians who first published the I2 warned against using thresholds for this statistic and presented a rough guide for the interpretation of I2, which is not congruent with the values proposed by the authors of this systematic review.26,28

Conclusions

The validity of the primary outcomes of this systematic review should be considered in the context of its numerous limitations. Replicating or updating of this review will be difficult, because of these shortcomings. Adverse effects of interventions were also not assessed. However, not only the authors of this review are responsible for its limitations, but also its peer-reviewers and editors as well as the methodologists who have launched the NOS without sufficient validation and guidance.

The secondary outcomes on the rates of implant-root contact of self-drilling and self-tapping insertion techniques for orthodontic mini-implants also have low validity, because only articles that were eligible for the primary research question, ie, just two studies, were examined for these outcomes, and definitions of implant-root contact, ie touching or penetration of the root, were not given.8

Practice point

-

Because of the numerous limitations in this systematic review, we have no confidence that the success rates of self-drilling and self-tapping insertion techniques of orthodontic mini-implants are similar. We also have no confidence that the rate of implant-root contact is similar for both techniques.

-

Because of the shortcomings and because adverse effects of interventions were not assessed, we believe that practitioners should not consider the findings of this systematic review until better evidence-based knowledge on this research topic will be created.

References

Yi J, Ge M, Li M, Li C, Li Y, Li X, Zhao Z . Comparison of the success rate between self-drilling and self-tapping miniscrews: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 2016; pii: cjw036. [Epub ahead of print].

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007; 7: 10.

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1013–1020.

Risk of bias in systematic reviews (ROBIS). ROBIS tool and the ROBIS guidance document. [online] Available from: http://www.robis-tool.info/ [Accessed 13 August 2016]

Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, et al; ROBIS group. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 69: 225–234.

O'Connor D, Green S . Higgins JPT (editors). Chapter 5: Defining the review question and developing criteria for including studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [online] Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Accessed 18 August 2016].

Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR). The methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews (Version 2.3 02 December 2013). [online] Available from: http://editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR_conduct_standards%202.3%2002122013_0.pdf [Accessed 19 August 2016].

Meursinge Reynders R, Ladu L, Ronchi L, et al. Insertion torque recordings for the diagnosis of contact between orthodontic mini-implants and dental roots: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2016; 5: 50.

PROSPERO: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. University of York, UK. [online] Available from: [http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/] [Accessed 16 August 2016].

Enabling Open Scholarship (EOS). [online] Available from: http://www.openscholarship.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/200909/open_access_institutional_repositories.pdf [Accessed 14 August 2016].

The directory of Open Access Repositories (Open DOAR). [online] Available from: http://www.opendoar.org/ [Accessed 14 August 2016].

Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR). [online] Available from: http://roar.eprints.org/ [Accessed 14 August 2016].

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization (ICTRP). [online] Available from: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx [Accessed 14 August 2016].

Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. Br Med J 2010; 340: c365.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J . Altman DG ; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6: e1000097.

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P . The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [online] Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [Accessed 10 August 2016].

Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP . Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36:666–676.

Hartling L, Hamm M, Milne A, Vandermeer B, Santaguida PL, Ansari M, Tsertsvadze A, Hempel S, Shekelle P, Dryden DM . Validity and inter-rater reliability testing of quality assessment instruments. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10021-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC039-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2012. [online] Available from: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm [Accessed 14 August 2016].

Hartling L, Hamm MP, Milne A, et al. Testing the risk of bias tool showed low reliability between individual reviewers and across consensus assessments of reviewer pairs. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66: 973–981.

Hartling L, Milne A, Hamm MP, et al. Testing the Newcastle Ottawa Scale showed low reliability between individual reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66: 982–993.

Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M . Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers' to authors' assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14:45.

Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. [online] Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/ [Accessed 15 August 2016].

Sterne JAC, Higgins JPT . Reeves BC on behalf of the development group for ACROBAT-NRSI. A Cochrane Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool: for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI), Version 1.0.0, 24 September 2014. [online] Available from: http://www.riskofbias.info [Accessed 26 November 2016].

The Nordic Cochrane Centre. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]: version 5.3. Copenhagen: the Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT . Rothstein HR: Chapter 40: When does it make sense to perform a meta-analysis? In Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Edited by Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG . Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [online] Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Accessed 16 August 2016].

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR . Chapter 13: Fixed-effect versus random-effects models. In: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, (editors). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med. J 2003; 327: 557–560.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Zhihe Zhao, Department of Orthodontics, State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, #14, 3rd Section, South Renmin Road, Chengdu 610041, PR China. E-mail: zhzhao@scu.edu.cn

Yi J, Ge M, Li M, Li C, Li Y, Li X, Zhao Z. Comparison of the success rate between self-drilling and self-tapping miniscrews: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 2016; pii: cjw036. [Epub ahead of print] Review. PubMed PMID: 27166073.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reynders, R., Cacciatore, G. No confidence that success rates of self-drilling and self-tapping insertion techniques of orthodontic mini-implants are similar. Evid Based Dent 17, 111–113 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401203

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401203