Abstract

Design

Cluster randomised controlled trial.

Intervention

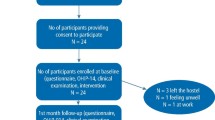

Clusters of adolescents (classrooms of 15- to 16-year-olds) in each school were allocated either into a control group or into an intervention group. The interventions consisted of peer cooperation (peer support) and peer interactive learning (observational learning) facilitated through feedback from a dentist (professional support). Three intervention sessions with preselected pairs of adolescents were delivered in the first three weeks. Gender, family socio-economic status (baseline) and different social-cognitive domain variables (baseline, six, and 12 months) were assessed using a questionnaire.

Outcome measure

Dental plaque levels were the primary outcome measure and they were measured at baseline, after the intervention measured only in the social-cognitive theory-guided group, at six and 12 months.

Results

At the six-month follow-up there was a statistically significant difference in means ± SD between the social-cognitive intervention group (27.4 ± 19.4) and the control group (35.1 ± 20.0). At the 12-month follow-up, there was no statistically significant difference in means ± SD between the social-cognitive intervention group (27.4 ± 18.5) and the control group (31.9 ± 17.8). Variations in dental plaque levels at different time periods were explained by the following predictors: family's socio-economic status, social-cognitive domain variables, group affiliation and baseline plaque levels.

Conclusions

Social-cognitive theory-guided interventions improved oral self-care of adolescents in the short term. This improvement lasted only for five months after the intervention was discontinued.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Caries is a highly prevalent condition in adolescence.1 Prevention and treatment present a major public health challenge, yet the majority of oral health strategies address prevention in younger children. There have been a number of studies exploring the effectiveness of interventions to improve oral health in childhood but again the focus is on younger children.2 Few studies use a social-cognitive theory (SGT) guided intervention, despite their association with health improvements in other fields. This study, therefore, represents a valuable contribution to the literature. Adolescence is a period of transition when children gain autonomy over their oral health related behaviours and oral health beliefs are established. Individuals with favourable oral health beliefs in adolescence present with better oral health as adults.3 The increased self-efficacy reported by participants in the treatment arm supports the idea that such beliefs are not fixed and can be successfully changed for the better. There are a number of issues relating to the methodology of the study. The method of random sampling and school selection are unclear. Participant demographics and characteristics that may have affected the outcome, eg additional learning needs, are not described. The study may be underpowered given the numbers lost to follow-up and the power calculation was based on individuals and did not take into account the effect of clustering. An intention-to-treat analysis may have been more appropriate given those lost to follow-up presented at baseline with the highest levels of plaque.

The need to use validated outcome measures with clinical relevance is well documented. The amount of plaque present on teeth may be a proxy measure of the effectiveness of tooth-brushing and fluoride exposure from toothpaste; but the measure used here (percentage of teeth surface covered in plaque) is not well recognised or validated. The clinical relevance of a 20% reduction is unclear.

Despite these limitations, the study addressed the reported aims. It suggests SGT based oral health interventions delivered in school by a dentist could reduce plaque levels and improve self-efficacy in the short-term. To support long-term changes, it reinforces the need for oral health interventions to be reinforced over time. It would be more cost-effective to use other members of the dental team or trained oral health promoters to deliver similar programs.

Practice point

-

Oral health promotion delivered by a dentist in schools can improve oral health behaviours and beliefs in adolescence but must be reinforced over time for long-term benefits.

-

When assessing adolescent oral health risk, previous oral health and deprivation status continue to be the main predictors of future oral health status.

References

Pitts N, Chadwick B, Anderson T . Report 2: Dental Disease and Damage in Children England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Children's Dental Health Survey 2013. Online: National Statistics Office, 2015.

Cooper AM, O'Malley LA . Elison SN, et al. Primary school-based behavioural interventions for preventing caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 5: CD009378.

Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Poulton R . Oral health beliefs in adolescence and oral health in young adulthood. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 339–343.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Jolanta Aleksejuniene, Department of Oral Health Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of British Columbia, 2199 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC Canada V6T 1Z3. E-mail: jolanta@dentistry.ubc.ca

Aleksejūnienė J, Brukienė V, Džiaugyte L, Pečiulienė V, Bendinskaitė R. A theory-guided school-based intervention in order to improve adolescents' oral self-care: a cluster randomized trial. Int J Paediatr Dent 2015; 16. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12164. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 25877514.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall-Scullin, E. Short-term improvement in oral self-care of adolescents with social-cognitive theory-guided intervention. Evid Based Dent 16, 110 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401132

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401132