Abstract

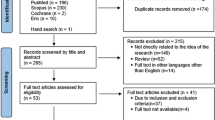

Data sources

PubMed, ERIC and PsycLIT. The database search was supplemented with manual search of the electronic archives of the following journals: Academic Medicine, Medical Education, Teaching and Learning in Medicine, Journal of Dental Education and European Journal of Dental Education. Further articles were retrieved from the reference lists of selected papers. The review covered the period 1976-2008.

Study selection

Studies were eligible if they presented original research using PBL in research settings compared with another educational method (at a whole curriculum level or as a single intervention). This review included both randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and comparative studies. Qualitative and quantitative designs were eligible.

Data extraction and synthesis

Three dental educators selected studies. It is not clear that there were predefined criteria. The studies showed considerable heterogeneity in their study designs, characteristics, outcome variables and results. A descriptive review of the data was presented.

Results

Sixty-nine studies were initially identified. The authors excluded 17 of these because they could not obtain full texts. Thirteen studies were excluded because they used purely qualitative data. Of the remaining 39 studies six were RCTs and 33 comparative studies. The RCTs gave little information about the curriculum design and used markedly different outcome measurements including test scores, personal characteristics and subjective approaches to learning and experiences. There was no overall difference in student performances between the integrated and the PBL curriculum but a significant difference in favour of these two when compared with a conventional curriculum. A modest advantage of PBL was noted in relational skills, humanistic attitudes and diagnostic accuracy. Test scores did not appear to be influenced by the use of PBL. Though PBL seems to have a good effect on several competencies after graduation no significant effects were observed in lifelong learning attitudes. Comparative studies on the whole showed a benefit from using PBL, for example in critical reasoning, problem solving abilities and creativity.

Conclusions

Some evidence exists that single PBL intervention in a traditional curriculum is an effective learning tool, though test results appear not to be affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

There have been several systematic reviews relating to problem-based learning (PBL) in health professional education. Desirable outcomes from PBL programmes have been noted compared with conventional programmes, but the differences are usually not major.1-6 This review by Polyzois et al. aims ‘to investigate and categorise existing evidence regarding the short and medium term effectiveness and reported benefits or drawbacks of PBL in health education.’ While categorising and summarising existing literature on the effectiveness of PBL can be a useful exercise, analysing the existing data and drawing inferences from the findings is fraught with difficulties. Unfortunately, details about the methods used to analyse the methodological quality of the papers included in the present review and to synthesise the data obtained are very limited.

It has been proposed that there are at least four reasons why trying to answer the question ‘Is PBL better?’ is unlikely to be particularly helpful:7, 8

-

there is often disagreement about what is meant by the term PBL

-

it is difficult to define ‘better’ when comparing different educational approaches

-

it is important to determine how PBL is implemented in a given situation

-

evaluation of curriculum-wide interventions is problematic, given the complex, multi-factorial nature of health profession curricula.

Polyzois and colleagues report on four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared whole curricula and two others focussed on single educational interventions. They noted that most of these studies provided little or no information about curriculum design or delivery. They considered that it was reasonable to put the greatest weight on findings from RCTs but admit that there are different views about their value in educational research. One is reminded of Norman's commentary in Medical Education, ‘RCT = results confused and trivial: the perils of grand educational experiments.’9

In addition to RCT studies, Polyzois et al. found 26 comparative studies at a whole curriculum level and seven focussed on shorter courses or interventions. Unsurprisingly, given the issues raised above, none of the comparisons at a whole curriculum level showed clear differences between PBL and conventional programmes. However, comparative studies of single PBL interventions in traditional programmes gave results that consistently favoured PBL. While the authors considered this finding to be ‘paradoxical’, it is not surprising given that it is more likely that confounding factors can be controlled in a focussed intervention.

Based on their findings, the authors pose the question ‘...could it be possible that multiple PBL interventions in a traditional curriculum are more effective than a PBL curriculum?’ This seems to be a very speculative suggestion, given the widely accepted importance of developing a consistent educational philosophy across programmes.10 The question is also highly unlikely to be testable.

For many health education researchers the debate has moved on from descriptive and justification type studies, to clarifying how and why different educational strategies work or do not work.11

Practice point

-

Dental education practice should be based on evidence.

-

More studies are needed to clarify how and/or why PBL works in dental education.

References

Albanese MA, Mitchell S . Problem-based learning: a review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Acad Med 1993; 68: 52–81.

Vernon DT, Blake RL . Does problem-based learning work? A meta-analysis of evaluative research. Acad Med 1993; 68: 550–563.

Colliver JA . Effectiveness of problem-based learning curricula: research and theory. Acad Med 2000; 75: 259–266.

Dochy F, Segers M, Van den Bossche P, Gijbels D . Effects of problem-based learning: a meta-analysis. Learning and Instruction 2003; 13: 533–568.

Newman M . Campbell Collaboration Systematic Review Group on the effectiveness of problem-based learning. A pilot systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of problem based learning. Newcastle upon Tyne (UK): University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Learning and Teaching Support Network, 2003.

Koh G C-H, Khoo HE, Wong ML, Koh D . The effects of problem-based learning during medical school on physician competency: a systematic review. CMAJ 2008; 178: 34–41.

Winning T, Townsend G . Problem-based learning in dental education: what's the evidence for and against ... and is it worth the effort? Aust Dent J 2007; 52: 2–9.

Townsend G, Winning T . Research in PBL – where to from here for dentistry? Eur J Dent Educ 2011; 15: 193–198.

Norman G . RCT = results confused and trivial: the perils of grand educational experiments. Med Educ 2003; 37: 582–84.

Cook DA . Avoiding confounded comparisons in education research. Med Educ 2009; 43: 102–104.

Cook DA, Bordage G, Schmidt HG . Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education. Med Educ 2008; 42: 128–133.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Ioannis Polyzois, School of Dental Science, Trinity College Dublin 2, Ireland. E-mail: Ioannis.Polyzois@dental.tcd.ie

Polyzois I, Claffey N, Mattheos N. Problem-based learning in academic health education. A systematic literature review. Eur J Dent Educ 2010; 14: 55–64

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Townsend, G. Problem-based learning interventions in a traditional curriculum are an effective learning tool. Evid Based Dent 12, 115–116 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400829

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400829