Abstract

Data sources

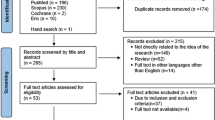

The search strategy was developed using Medline and adapted for the requirements of other databases. The strategy included all study types, enabling the retrieval of qualitative research. Databases searched were; Australian Education Index, ACP Journal Club, British Education Index, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Embase, Eric, LISA Medline, metaRegister of Controlled Trials, National Research Register, Psychinfo, REFER, Sociological Abstracts, Web of Knowledge. Bibliographies of relevant publications and review articles were scanned and relevant references were retrieved. No language restrictions were applied.*

*Information on databases searched provided by original authors as not included in published article.

Study selection

All study designs which evaluated whether clubs promote changes in learner reaction, attitudes, knowledge, skills, behaviour or patient outcomes in undergraduate, postgraduate and practice settings. Studies evaluating video/internet meetings or single meetings were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Each article was reviewed by two authors independently with pilot-tested data collection forms. No quality assessment was pre-specified.

Results

Eighteen studies were included. Studies reported improvements in reading behaviour (N=5/11), confidence in critical appraisal (N=7/7), critical appraisal test scores (N=5/7) and ability to use findings (N=5/7). No studies reported on patient outcomes. Sixteen studies used self-reported measures, but only four studies used validated tests. Interventions were too heterogeneous to allow pooling. Realist synthesis identified potentially 'active educational ingredients', including mentoring, brief training in clinical epidemiology, structured critical appraisal tools, adult-learning principles, multifaceted teaching approaches and integration of the JC with other clinical and academic activities.

Conclusions

The effectiveness of JCs in supporting evidence-based decision making is not clear. Better reporting of the intervention and a mixed methods approach to evaluating active ingredients are needed in order to understand how JCs may support evidence-based practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Journal clubs have been around for over 100 years.1 The earliest reference is found in a book of memoirs and letters by the British surgeon, Sir James Paget.2 The first formal journal club was established by Sir William Osler at McGill University in Montreal in 1875 'for the purchase and distribution of periodicals to which he could ill afford to subscribe as an individual'.3 Over the years, journal clubs have transformed to become an ubiquitous component of graduate medical and dental education; designed to teach critical appraisal skills to practitioners-in-training, and promote integration of best new evidence into clinical practice.

The current model of journal clubs is based on the premise that interactive learning, tailored to the needs of adult learners, will promote the uptake of current best evidence into clinical practice. Despite the widespread belief that journal clubs are effective avenues for bridging the gap between clinical research and practice, this tenet has rarely been tested.

The systematic review by Harris et al. addressed two questions: 'are journal clubs effective in supporting evidence based decision making?', and 'which elements of a journal club contribute to its effectiveness?'. In undertaking this review the authors took into account the educational methodology underlying concepts around adult learning, knowledge transfer and promotion of clinical behaviour change. The methodology of the systematic review itself was sound, albeit with some limitations that seem to be due to reporting rather than conduct. The overall strength of evidence was weak. Of the 18 studies identified, there were eight before-and-after studies, six questionnaires, one observational study, one case-control, one non-randomised and one randomised controlled trial. Duration of the studies ranged from three months to 15 years. Descriptions of the interventions were too heterogeneous to allow meta-analysis. The distinction between 'change in skill' (ie ability to apply new knowledge to clinical situations) and 'change in knowledge' (such as accessing and critically appraising the literature) was not consistent within or between studies.

Despite the limitations of the evidence, a qualitative summary identified two key messages in this review. The first is that to ensure success of a journal club, the format must be tailored to the educational needs of the learner - be they undergraduates, graduate students or practitioners. The second is that, while there is no ideal format for a journal club, there are components that contribute to its effectiveness in changing behaviour. These include mentoring, didactic support, the use of structured review instruments, adhering to the principles of adult learning, using multifaceted approaches to learning and integrating the learning with other academic and clinical activities. For example, undergraduate students may need didactic support for clinical epidemiology and biostatistics, with emphasis on learning critical appraisal skills. Journal clubs for residents should ensure the content is directly applicable to ongoing patient cases, with mentors providing support for application of critical appraisal skills in clinical settings. Continuing education for practitioners is likely to be most effective in promoting and maintaining changes in clinical practice if there are regular meetings of small groups in which strong relationships can be developed.

References

Linzer M . The journal club and medical education: over one hundred years of unrecorded history. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63: 475–478.

Paget S . Memoirs and letters of Sir James Paget. pp 42. London: Longmans, Green and Co 1901.

Cushing H . The Life of Sir William Osler, Volume 1. pp 132–133, 154. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1926.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: J Harris, School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, 30 Regent Street, Sheffield S1 4DA, UK. E-mail: janet.harris@sheffield.ac.uk

Harris J, Kearley K, Heneghan C, et al. Are journal clubs effective in supporting evidence-based decision making? systematic review. BEME Guide No.16. Med Teach 2011; 33: 9–23.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matthews, D. Journal clubs most effective if tailored to learner needs. Evid Based Dent 12, 92–93 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400818

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400818