Abstract

Data sources

The Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Registry, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline and Embase were consulted to find relevant work. Searches were made by hand of numerous journals pertinent to oral implantology. There were no language restrictions.

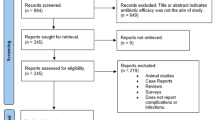

Study selection

Randomised controlled clinical trials (RCT) with a followup of at least 3 months were chosen. Outcome measures were prosthesis failures, implant failures, postoperative infections and adverse events (gastrointestinal, hypersensitivity, etc.).

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality and extracted relevant data from included studies. The estimated effect of the intervention was expressed as a risk ratio together with its 95% confidence interval (CI). Numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT) were calculated from numbers of patients affected by implant failures. Meta-analysis was done only if there were studies with similar comparisons that reported the same outcome measure. Significance of any discrepancies between studies was assessed by means of the Cochran's test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic.

Results

Only two RCT met the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis of these two trials showed a statistically significantly higher number of patients experiencing implant failures in the group not receiving antibiotics (relative risk, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.06–0.86). The NNT to prevent one patient having an implant failure is 25 (95%CI, 13–100), based on a patient implant failure rate of 6% in people not receiving antibiotics. The following outcomes were not statistically significantly linked with implant failure: prosthesis failure, postoperative infection and adverse events (eg, gastrointestinal effects, hypersensitivity).

Conclusions

There is some evidence suggesting that 2 g of amoxicillin given orally 1 h preoperatively significantly reduces failures of dental implants placed in ordinary conditions. It remains unclear whether postoperative antibiotics are beneficial, and which is the most effective antibiotic. One dose of prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental implant placement might be recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Although procedures for osseointegration of dental implants are remarkably predictable, failures do occur and are sometimes attributed to bacterial contamination at the surgical site, which could inhibit osseointegration of the implant.1

The use of antibiotic prophylactic prior to surgery has been proposed to prevent this complication. For example, Dent et al. (1997) published the potential benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to implant surgery.2 Their study showed lower 6-month post-insertion failure rates, of 1.5% with antibiotic prophylaxis as compare to 4% when none was given (i.e, absolute reduction in implant failures of 2.5%) . The same group published a 3-year followup and reported an even larger absolute reduction in implant failures of 5.5%.3

Since dental implants have very low failure rates, these absolute reductions in implant failures with use of antibiotic prophylaxis are worth closer examination. The Schwartz and Larson systematic review published in 2007 concluded, based on a nonrandomised study, two observational studies and one case–control study, that there was no evidence that preoperative antibiotic treatment reduces the occurrence of osseointegration failure, compared with controls not given the prophylaxis.4 Six months later, however, Esposito et al. (2008) published the above Cochrane systematic review showing that a difference does seem to exist.

The review tried to answer the following clinical question: will antibiotic prophylaxis reduce the number of patients having complications following dental implants at 6 months after surgery? Although the protocol for this well-designed Cochrane review was originally conceived by the authors in 2003 , they were not able to execute it until data from two recently published RCT (Abu-Ta'a et al., 2008; Esposito et al., 2008) met their inclusion criteria.5,6 Both of these RCT were published just before the review's deadline of 9 January 2008 and were therefore not available to Schwartz and Larson (2007)4 at the time they conducted theirs.

Esposito was the primary author of this review and of one of the RCT that met its inclusion criteria. This is a potential source of bias, especially since the reviewers considered the Esposito study to be of higher quality than the other RCT, and thus gave it more weight in the final meta-analysis. This first author probably designed a trial that would best meet the criteria of his Cochrane review, which he prepared 5 years earlier, but heterogeneity analysis did show these two studies to be very similar (Cochrane and I2 statistics were very low), justifying amalgamation of their respective data for meta-analysis.

It is interesting that, individually, each of these studies showed no statistical difference in implant failures between the intervention and control groups, yet, when combined for a meta-analysis, a statistical difference was realised. This is an example of how a meta-analysis can increase the statistical power of studies and thus reduce the likelihood of making a Type II error, ie, incorrectly accepting the null hypothesis.

A systematic review of RCT is the evidential pinnacle of evidence-based healthcare.7 Although this systematic review essentially meets this standard, it is still based on a pool of 410 patients from only two RCT which, as stand alone studies, showed no statistical difference. Nevertheless, it does offer evidence that could justify the routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis for dental implant surgery. In order to confirm the conclusion and enhance the statistical power of this meta-analysis, more RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria of this review are needed. A search (15 November 2008) of the Current Controlled Trials website unfortunately yielded no such studies currently registered (www.controlled-trials.com).

Practice point

There is some evidence to suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis reduces failure of dental implants placed in ordinary conditions.

References

Esposito M, Hirsch JM, Lekholm U, Thomsen P . Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants. I. Success criteria and epidemiology. Eur J Oral Sci 1998; 106:527–551.

Dent CD, Olson JW, Farish SE, et al. The influence of preoperative antibiotics on success of endosseous implants up to and including stage II surgery: a study of 2,641 implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 55(suppl. 5):S19–S24.

Laskin DM, Dent CD, Morris HF, Ochi S, Olson JW . The influence of preoperative antibiotics on success of endosseous implants at 36 months. Ann Periodontol 2000; 5:166–174.

Schwartz AB, Larson EL . Antibiotic prophylaxis and postoperative complications after tooth extraction and implant placement: a review of the literature. J Dent 2007; 35:881–888.

Esposito M, Cannizzaro G, Bozzoli P, Consolo U, Felice P, Ferri V . Efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics for dental implants: a multicentre placebo-controlled randomized clinical trail. Eur J Oral Implant 2008; 1:23–31.

Abu-Ta'a M, Quirynen M, Teughels W, van SD . Asepsis during periodontal surgery involving oral implants and the usefulness of peri-operative antibiotics: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35:58–63.

Sackett DL, Strauss SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB . Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd Edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Luisa M Fernandez Mauleffinch, Cochrane Oral Health Group, MANDEC, School of Dentistry, University of Manchester, Higher Cambridge Street, Manchester M15 6FH, UK. E-mail: luisa.fernandez@manchester.ac.uk

Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Talati M, Coulthard P, Oliver R, Worthington HV. Intervention for replacing missing teeth: antibiotics at dental implant placement to prevent complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008, issue 3

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balevi, B. Do preoperative antibiotics prevent dental implant complications?. Evid Based Dent 9, 109–110 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400612

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400612

This article is cited by

-

So führen wir die zahnärztliche Implantologie bei Patienten mit entzündlich rheumatischen Erkrankungen durch

Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie (2023)

-

An investigation of antibiotic prophylaxis in implant practice in the UK

British Dental Journal (2012)