Abstract

Design

A case–control study was carried out at the University of North Carolina School of Dentistry in the US.

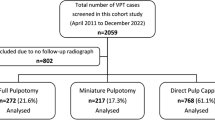

Participant selection

Dental charts from the university's dental clinical were audited for patients who had a single-cast crown between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2002. Cases were defined as individuals who underwent root canal treatment at some time after the insertion of a single-cast crown up to 1 July 2004. The control group consisted of people who did not have root canal treatment after the insertion of a full-cast crown.

Data analysis

A list of 24 clinical factors was compared between groups (Table 1). Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determine which preoperative nonprocedural factors were predictive of root canal treatment subsequent to a full-cast crown.

Results

A total of 6612 single-cast crowns (cast metal or porcelain fused to metal) were inserted during the 5-year period of interest. Of these, 5743 crowns, identified from 3357 patients' records (ie, the study subjects), were determined not to have undergone root-canal treatment prior to full-cast crown restorative treatment. Ninety-two subjects were initially determined to be eligible cases; ninety-two subjects were also therefore randomly selected from the remaining 3265 subjects to make up the control group. Twenty-six of the cases and 21 members of the control group were excluded because of incomplete records. The final case and control groups comprised 66 and 71 subjects respectively. Only subjects' age at the time of restorative treatment and their post-cementation tooth sensitivity was statistically significantly different between the two groups (P<0.05). Multiple logistic regression determined the statistically significant (P<0.05 ) predictors of case status: these were a patient's age and also the subgroup to which they were allocated according to the extent of pre-operative coronal and root destruction, on the basis of the restorative core size (more than three restored surfaces; Table 2).

Conclusion

The age of a patient and the extent of coronal and root destruction can be used to predict the future need for root canal treatment on teeth for which a single-cast crown is planned.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

The risk of subsequent endodontic devitalisation is on the mind of every dentist when planning treatment of a tooth with a cast crown. Probabilities have been reported from 2.6% to as high as 25% that root canal treatment will follow cast crown insertion.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Kirakozova and Caplan's case–control study here aimed to determine which clinical variables, present at the time when treatment is being planned for a single-cast crown, are predictive of future root canal treatment. This is a question very pertinent to clinical practice.

The authors searched their dental school clinic's computer database, seeking patients who had a cast crown placed in a specific 5-year period. Cases (ie, subjects for the study) were clearly defined as those individuals who had a crown placed between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2002 and who afterwards underwent root canal treatment any time before 1 July 2004. In other words, the authors allowed a lag period of 18 months between the last date a crown could be placed (31 December 2004) and a catastrophic endodontic event occurring.

Controls were defined as subjects who did not undergo subsequent root canal therapy. It is possible, however, that a crown could have been inserted on 30 December 2002 with the patient reporting a catastrophic endodontic event on 2 July 2004: this subject would be included in the control group and not amongst the cases. Although it is possible that 18 months is sufficient time for all subsequent endodontic problems to arise, we cannot be sure unless the dental histories of all cases and controls are clearly given. This problem demonstrates the weakness of retrospective case–control studies when the histories of the cases and controls are not matched with respect to time of treatment and time of event. Without knowing the restorative-treatment date distribution between the two groups, we are not sure if cases are disturbed evenly though out the observation period or were limited to teeth restored during a specific period (eg, was 1999 a particularly bad year for crowns?).

The failure of the authors to report and account for teeth lost to follow-up, and lost to possible subsequent extraction, also threatens the validity of the results. Although the authors claim that they accounted for controls who may have been root-treated outside the clinic, nowhere are these accounted for as possible cases. In addition, it is likely that some patients elected to have the abscessed crowned tooth extracted rather than undergo root canal treatment.

All these factors may have resulted in under-reporting the number of cases of irreversible endodontic damage. This seems to be consistent with the data presented here, because 95 teeth (out of a total of 5743 teeth eligible for this study) reported subsequent root canal treatment. This amounts to only 1.6% having subsequent root canal treatment to a crowned tooth — less than half the figure reported by others.1, 2

Furthermore, the authors failed to perform a sample size calculation from the start. There are ample data in the literature cited in their study for the authors to have at least attempted to calculate the size of study required to minimise a type-2 error (a false negative). The small sample size used here probably explains why the age of subjects was the only pre-operative variable to show a statistical difference between the case and control groups. The 95% confidence interval (CI) just misses crossing the point of no effect [odds ratio (OR) of 1.0]. Although the authors subgrouping of the “extent of coronal and root destruction”, based on the size of the pretreatment restoration (ie, more than three restored surfaces), showed a statistically significant OR of 7.6, the 95% CI is huge, with its lower limit barely avoiding the point of no effect as well.

The authors briefly mention that, although post-cementation tooth sensitivity appeared to be a statistically significant postoperative factor, they did not include it in the regression analysis because it is not a pre-procedural clinical factor that a clinician can use when planning a crown. Although this is true, as a clinician I found this variable of particular interest: I am often confronted with such a clinical scenario and wondering what is the likelihood of irreversible endodontic damage. I calculated a high OR of 20.1 with a 95% CI of 12.9–31.3. If valid, this predicts subsequent root canal treatment on crowned teeth that develop post-cementation sensitivity.

Although this study does have shortcomings, some of which are acknowledged by the authors in their discussion, they should be commended for attempting to investigate such a relevant clinical question. I agree with their conclusion that this study's findings, “demonstrate the need for prospective study designs that could identify more and better predictors of subsequent [root canal treatment] in teeth receiving crowns”.

References

Cheung GS, Lai SC, Ng RP . Fate of vital pulps beneath a metal-ceramic crown or a bridge retainer. Int Endod J 2005, 38:521–530.

Lockard MW . A retrospective study of pulpal response in vital adult teeth prepared for complete coverage restorations at ultrahigh speed using only air coolant. J Prosthet Dent 2002, 88:473–478.

Saunders WP, Saunders EM . Prevalence of periradicular periodontitis associated with crowned teeth in an adult Scottish subpopulation. Br Dent J 1998, 185:137–140.

Valderhaug J, Jokstad A, Ambjornsen E, Norheim PW . Assessment of the periapical and clinical status of crowned teeth over 25 years. J Dent 1997, 25:97–105.

Jackson CR, Skidmore AE, Rice RT . Pulpal evaluation of teeth restored with fixed prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1992, 67:323–325.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Anna Kirakozova, Department of Endodontics, University of North Carolina, School of Dentistry, CB#7450, Chapel Hill NC 27599, USA. E-mail: anna_kirakozova@dentistry.unc.edu

Kirakozova A and Caplan DJ. Predictors of root canal treatment in teeth with full coverage restorations. J Endod 2006; 32:727–730

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balevi, B. Patient's age and extent of coronal and root destruction predict root canal treatment subsequent to after a full-cast crown. Evid Based Dent 7, 98–99 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400447

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400447