Abstract

Data sources Searches for relevant studies were made using the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction group specialised register Cochrane CENTRAL , Medline, Embase, CINAHL (Central Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Healthstar (1975–2004), ERIC, Education Resources Information Centre (1967–2004), PsycINFO (1984–2004), the National Technical Information Service database, Dissertation Abstracts Online, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness and Web of Science.

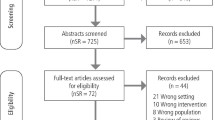

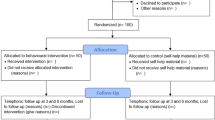

Study selection Randomised and pseudo-randomised clinical trials were chosen that assessed tobacco cessation interventions, were conducted by oral health professionals in the dental office or community setting, and which had at least 6 months of follow-up.

Data extraction and synthesis Two authors independently reviewed abstracts for potential inclusion and abstracted data from included trials. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results Six clinical trials met the inclusion criteria. All studies assessed the efficacy of interventions for smokeless tobacco users, but only one also included cigarette smokers. All studies employed behavioural interventions but only one offered pharmacotherapy as an interventional component. All studies included an oral examination. Pooling of the studies suggested that interventions conducted by oral health professionals increase tobacco abstinence rates (odds ratio, 1.44; 95% confidence interval, 1.16–1.78) after 12 months or longer. Heterogeneity was evident (I2, 75%) and could not be adequately explained through subgroup or sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions Available evidence suggests that behavioural interventions dealing with tobacco use that are conducted by oral health professionals, which include an oral examination, in the dental office and community setting, may increase tobacco abstinence rates in smokeless tobacco users. Differences between published studies limit the ability to make conclusive recommendations about interventions that should be incorporated into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

This Cochrane review investigates four different hypotheses, all of which focus on the effectiveness of using dental personnel to deliver tobacco cessation interventions. The first point of note is the limited amount of literature on this topic. Despite a fairly inclusive approach, the authors only identified six studies that they could include. Five trials had been targeted at smokeless tobacco users, whereas one alone targeted both smokers and smokeless tobacco users. Therefore, although the authors concluded that interventions for smokeless tobacco users in the dental setting may increase the odds of quitting tobacco, there were no appropriate studies that could be used to draw any conclusions with regard to cigarette smokers.

This is a timely publication, however, in view of the recent publication in England and Wales of Choosing Better Oral Health (CBOH), the Dental Public Health white paper.1 CBOH was published to complement the introduction of the new dental contracts, with the aim of encouraging a more preventive approach in dentistry. CBOH lists smoking cessation as one of the six key steps to improving oral health. The document complements Choosing Health,2 a Public Health white paper that also emphasises the importance of promoting tobacco cessation.

There is a new drive within the UK National Health Service (NHS) to promote disease-prevention within the general population. Tobacco-use is a risk factor in a range of diseases including heart disease and various cancers: it is not surprising that achieving lower rates of tobacco-use in the country is high on the Department of Health's list of priorities. The view of health experts is that all healthcare professionals, including dental team members, should be delivering the tobacco cessation message to achieve maximum effect. There are good reasons for believing that this approach might be effective. The range of healthcare professionals used by the public includes dental teams, and the effects of smoking are demonstrable in the mouth. Smoking is also a risk factor for oral cancer, which carries a mortality rate of 50%.

Previous research has indicated that most dentists believe that they should offer tobacco cessation advice, although many were worried about patients leaving the practice.3,–6 Results from a US study, which indicated that the majority of patients were in favour of these services,7 should allay some of these fears. Without evidence, however, the effectiveness of any dental intervention remains theoretical. With the current difficulties in accessing NHS dentistry, one could argue that it would be more worthwhile for dental teams to deliver dental treatment to a greater number of individuals than to engage in tobacco cessation activity which has no evidence of effectiveness. After all, Primary Care Trusts have dedicated Smoking Cessation Advice Services whose sole responsibility is to encourage and support tobacco cessation within their populations.

Dental teams need to consider what their role is within the healthcare system with regard to health promotion. This needs to be balanced against their responsibility of delivering dental care to their patients and the dental treatment activity they are expected to deliver under the new contracts. Perhaps a reasonable position would be for dental teams to raise awareness of the impact of tobacco use on oral and general health and then direct patients to other sources for further advice and support.

Practice point

-

Dental teams need to raise the impact of tobacco use on oral and general health with their patients and refer accordingly.

References

Anon. Choosing Better Oral Health: an Oral Health Plan for England. London. Department of Health Dental and Ophthalmic Services Division; 2005.

Anon. Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. London. Department of Health: 2004.

Clover K, Hazell T, Stanbridge V, Sanson-Fisher R . Dentists' attitudes and practice regarding smoking. Austral Dent J 1999; 44:46–50.

Chestnutt IG . What should we do about patients who smoke? Dent Update 1999; 26:227–231.

Skegg JA . Dental programme for smoke-free promotion: attitudes and activities of dentists, hygienists, and therapists at training and 1 year later. NZ Dent J 1999; 95:55–57.

John JH, Thomas D, Richards D . Smoking cessation interventions in the Oxford region: changes in dentists' attitudes and reported practices 1996-2001. Br Dent J 2003; 195:270–275.

Campbell HS, Macdonald JM . Tobacco counselling among Alberta dentists. J Can Dent Assoc 1994; 60:218–220. sed controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. J Am Med Assoc 1996; 276:637–639.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Alan Carr, Department of Dental Specialties, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, 200 1st Street Southwest, Rochester MN 55905, USA. E-mail: carr.alan@mayo.edu.

Carr AB, Ebbert JO. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; 2006, issue 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

John, J. Tobacco cessation counselling interventions delivered by dental professionals may be effective in helping tobacco users to quit. Evid Based Dent 7, 40–41 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400400

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400400