Key Points

-

This case report presents the rare phenomenon of an ectopic salivary gland in the anterior mandible which mimicked a radicular cyst.

-

Mandibular radiolucent lesions can cause diagnostic problems and diagnosis cannot be made from radiographs alone.

-

It is essential to undertake clinical examination and relevant special investigations to help reach a diagnosis.

Abstract

Ectopic salivary gland inclusions in the mandible are a rare phenomenon. Classically as described by Stafne1 they have been found in the posterior mandibular region. Cases affecting the anterior mandible are even more unusual. We report a case of ectopic salivary gland tissue in the anterior mandible. In our discussion we emphasise the need for a thorough history, examination and relevant investigations. Mandibular radiolucencies can prove a pitfall for the unwary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

A 45-year-old female patient was referred to the Oral and Facial Surgery Department at Sunderland Royal Hospital by her general dental practitioner. The patient complained of two firm painless swellings behind her lower incisors. She felt that the right swelling enlarged intermittently.

The patient's only current medication was thyroxine. She was otherwise generally fit and well with no other medical problems.

Clinical examination revealed a fit and well patient with no extra-oral pathology. No cervical lymph nodes were palpable and there was no mental nerve paraesthesia. Intra-orally the soft tissues were unremarkable. Bony hard prominences were noted in both right and left lingual alveolar regions. These clinically appeared as mandibular tori. The right torus was considerably larger than the left, extending from LR1 (41) to LR3 (43). The left torus was associated with LL2 (32) and LL3 (33) only. Both were sessile in nature covered by healthy pink oral mucosa. No other buccal or lingual swellings were palpable and the anterior floor of mouth was unremarkable.

The anterior dentition was healthy with no evidence of caries. Generalised chronic adult periodontal disease was noted both clinically and radiographically. None of these teeth were mobile or tender to percussion and LR4 (44) to LL1 (31) tested vital to electronic pulp testing.

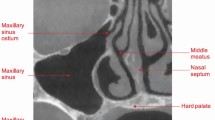

In view of the history of intermittent swelling a dental panoramic tomogram (DPT) was undertaken (Fig. 1). This demonstrated a large radiolucency extending from apical to LR1 (41) to distal to LR4 (44). A lower anterior occlusal radiograph, and periapical films of LR4 (44) to LL1 (31) region were also undertaken (Fig. 2). The occlusal film demonstrated the radio-dense tori. The periapical films demonstrated the well-defined radiolucency apical to LR4 (44) to LR2/LR1 (42/41) visible on the DPT. The lesion demonstrated corticated, well-defined margins and appeared distinct from the apices of the teeth, the lamina dura of which were intact.

It was decided to explore the lesion, and the patient was appropriately consented and listed for the procedure.

Procedure

The patient was treated under local anaesthetic and intravenous sedation. An envelope mucoperiosteal flap was raised from LR4 (44) to LR1 (41) with an anterior sulcal relieving incision. The mental nerve was identified and protected. No buccal lesion was visualised. A rose head bur in an irrigating surgical hand-piece was used to create a bony window. The cystic lesion lay deep to the cortex and measured approximately 15 mm by 10 mm in lateral and vertical dimensions respectively. The fibrous sac was yellowish in colour and firm. It was readily enucleating from its lateral margins with an excavator. Lingually, the lesion was tethered, appearing to perforate the lingual cortical plate, inferiorly and distinct from the torus. The lesion was dissected free of the lingual tissues which were seen to draw into the lingual defect as the lesion was put under tension buccally. A small floor of mouth perforation was noted and a single resorbable suture was used to close the wound. The enucleated specimen was partially ruptured (the contents of which appeared firm and homogenous to the naked eye) and was sent for histopathology. The site was thoroughly irrigated, bony margins were smoothed, and flap closed with resorbable sutures.

The patient was reviewed at 2 weeks. The surgical site was seen to be healing well with good gingival contours. The floor of mouth perforation had also healed uneventfully, and mental nerve sensation was normal.

Histopathology report

The tissue consisted of minor salivary gland lobules with mild chronic inflammatory changes only. The findings were consistent with that of ectopic salivary gland tissue.

The patient was further reviewed 5 weeks later and reported that the right swelling had increased in size once more but was not painful. Clinically there was no change to the lingual alveolus compared with the clinical photographs. A post-operative peri-apical radiograph demonstrated the same well-corticated radiolucency as had been previously noted with no bony infill at that stage (Figs 3, 4). The patient was reassured and further clinical and radiographic follow-up has been arranged.

Discussion

Ectopic salivary gland tissue occurs in many sites within the head and neck region and has even been found in other anatomical sites including anal mucosa! Head and neck site involvement includes the lateral and posterior neck, tongue, middle ear, thyroid, pituitary gland and mandible.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Salivary gland inclusion within the mandible is a rare phenomenon. Classically it occurs in the posterior region as described by Staphne.1 Ectopic glandular inclusion in the anterior mandible is even more unusual.2,5

Clinically and radiologically these entities can present diagnostic problems as they have similar appearance to periapical lesions. In the case presented we had the additional element of a prominent mandibular torus. Correct diagnosis could only be established after surgical exploration and histological examination. Whilst this is a rare entity, it would be prudent to keep it in mind when confronted with radiolucent areas in the mandible. It is recommended that vitality testing of apparently 'involved' teeth is undertaken and good quality peri-apical radiographs are obtained. The peri-apical radiographs may give a clue to its presence, as the periodontal ligament remains intact.

Ultimately diagnosis can only be made histologically after biopsy.

References

Staphne EC . Bone cavities situated near the angle of the mandible. J Am Dent Assoc 1942; 29: 1969–1972.

Miller AS, Winnick M . Salivary Gland inclusions in the anterior mandible. Oral Surg 1971; 31: 790–797.

Batsakis JG . Heterotopic and accessory salivary tissues. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1986; 95: 434–435.

Botrill ID, Chawla OP, Ramsay D . Salivary gland choristoma of the middle ear. J Laryngol Otol 1992; 106: 630–632.

Stene T, Pedersen KN . Aberrant salivary gland tissue in the anterior mandible. Oral Surg 1977; 44: 72–75.

Hatziotis JC, Trigonidis GJ . Aberrant salivary gland of the tongue. J Oral Surg 1974; 32: 620–621.

Weitzner S . Ectopic salivary gland tissue in submucosa of rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 1983; 26: 814–817.

Kato T, Abe H, Miyamachi K, Hida K, Taneda I, Ogata A . Ectopic salivary gland within the pituitary gland. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1988; 28: 930–933.

Marshall JN, Soo G, Coakley FV . Ectopic salivary gland in the posterior triangle of the neck. J Laryngol Otol 1995; 109: 669–670.

Morimoto N, Ogawa K, Kanzaki J . Salivary gland choristoma in the middle ear; a case report. Am J Otolaryngol 1999; 20: 232–235.

Guerrissi JO . Cervical by ectopic salivary gland. J Craniofac Surg 2000; 11: 394–397.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dorman, M., Pierse, D. Ectopic salivary gland tissue in the anterior mandible: a case report. Br Dent J 193, 571–572 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801629

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801629