Abstract

Aim To assess the use of dental services, barriers to uptake of dental care and attitudes to regular dental examinations and the prevalence of tobacco and paan chewing habits in a group of Bangladeshi medical care users.

Design Multi-centre cross-sectional study.

Setting Four general medical practices' waiting areas in Tower Hamlets.

Subjects Bangladeshi adults aged 40 years and over.

Intervention An interview schedule.

Main outcome measures The prevalence of tobacco smoking and paan chewing with or without the addition of tobacco. The use of dental services, barriers to the use of dental services and attitudes to regular dental examinations.

Results Results were obtained from 158 subjects (response rate 85%). 25% of the whole sample had never visited a dentist. These were significantly (P < 0.05) more likely to be women, who also thought regular check-ups were of little value. In their use of health services 73% experienced language difficulties. 33% of the sample were tobacco smokers. Paan was chewed by 78% of the sample with significantly (P < 0.05) more females than males adding tobacco to their quid and chewing more frequently than males.

Conclusion There are considerable barriers to be overcome if dental practices are to be the site for oral cancer screening and oral health promotion in this population. There are sex differences in reported behaviour and attitudes about use of dental services and in tobacco and paan use in this Bangladeshi sample. Further research is needed to establish why this ethnic minority attend general medical practices but not general dental practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Morbidity and mortality are high from oral cancer and there is a need for improved primary prevention. This should involve risk-factor reduction in the UK population as a whole as well as targeted initiatives on at-risk groups or individuals.1 Oral cancer may arise de novo although in high prevalence areas such as Southern Asia it is usually preceded by a so-called precancerous lesion — a red (erythroplakia) or a white (leukoplakia) patch.2 In India almost all oral cancers originate from leukoplakias.3 Secondary prevention is aimed at the early recognition of oral cancer. Treatment of precancerous or small (less than 2 cm) lesions results in an improved prognosis and causes limited morbidity.4 The UK Working Group on Screening for Oral Cancer and Pre-cancer5 recommended that screening for oral cancer should form part of a general oral examination by dentists and that all adults should be encouraged to attend for annual check ups. However, several studies have shown that among most minority ethnic groups there is a symptom oriented view in relation to use of dental services. 6,7,8

In India and other South Asian countries oral cancer is the most common cancer accounting for over 40% of all malignancies.9 Relative frequency is high in Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka.10 Paan (betel quid) chewing with tobacco and smoking is associated with an increased risk of oral cancer11,12 although a recent study13 found that areca nut chewing by itself was carcinogenic. Paan chewing has a long history in South Asian communities and it is associated with many social and religious traditions.14 The method and usage of the constituents of paan varies between countries, communities and individuals. Three principal ingredients, a leaf of the betel vine (Piper betle), areca nut and lime are necessary for the term paan to be used. Tobacco is frequently added to the paan quid. Within the UK, paan chewing is practised within Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities.15 Recent investigations into paan chewing in the UK have found that the habit is very widespread among Bangladeshis.15,16,17

These issues emphasize the need for more information on the use of dental services, barriers to the uptake of dental care, attitudes to regular dental examinations, and the paan and tobacco habits among Asians living in the UK.

Research into the health of ethnic minority groups is often restricted by methodological difficulties.18 The most practical and efficient means reported in the literature of identifying a sample has been the use of general medical practices,8,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 especially as it has been estimated26 that only 2% of 'black' and 'Asian' groups were not registered with a general practice in inner London. This approach circumvents the lack of a sampling frame needed for a random sample and the expense of using the address or electoral register to identify ethnic minority members.

Method

The study was confined to Bangladeshi adults aged 40 years and over attending general medical practices in Tower Hamlets. The Census data shows that Tower Hamlets, an inner-city borough of East London with high levels of social and economic deprivation, has the largest Bangladeshi population nationally. This minority ethnic group forms 23% (36,955) of the total borough population compared with 0.3% nationally. It is the largest ethnic group after the indigenous white population. Percentage distribution of other 'Asian' groups is only 2.8%. This age group was chosen since oral cancer screening is advised for individuals over the age of 40 years.27

The minimum sample size required was estimated to be 149 people. The sample size was calculated to give a standard error of less than 0.04 and the following assumptions were made: a population of 26,000 people, the 95% confidence interval level and a prevalence of 50% for all conditions. The prevalence of 50% was chosen because there were no previous data on this population and any other prevalence figure would propose a smaller sample size. To minimise possible problems with response it was decided to select at least 180 people. General medical practices that had a large attendance of Bangladeshi adults were identified and adults aged 40 years and over who were present in the waiting area of these practices were opportunistically sampled. Sampling sessions were carried out at different times of the week during morning and evening surgeries over a 3-month period, April to July 1994.

A range of data was collected using a structured interview schedule, which included open and closed questions. These questions were generated from previous investigations8,16 and from discussions with representative members of the Bangladeshi community. The interview schedule was previously evaluated in a pilot study of 12 individuals. To ensure question relevence minor modifications were made after the piloting with regards to the reporting of cultural habits and the use of health services. Two Sylheti speaking interviewers from the Bangladeshi community were used. They had both been trained and standardised to ensure that questions were asked in a similar manner and that all interviews were conducted in a uniform way. Questions were asked about their use of dental services and oral health promotion materials, the importance of regular check-ups for a healthy mouth, dental registration and barriers to using dental services, the use of paan and tobacco, what ingredients were included in the quid and with what frequency they practised the habit. Enquiry was also made regarding the age at which the habit commenced and if they perceived any health benefits from using it. Demographic data: age, sex, marital status, length of residence in the UK were also collected.

The study protocol was approved by the East London & City Health Authority (ELCHA) Local Research Ethics Committee. The data were prepared for analysis using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. The chi-squared test was used for the statistical analysis of the categorical data, and a statistical significance level of 5% was adopted.

Results

A total of 185 Bangladeshi adults aged 40 years and over were approached to take part in the study. Of these 158 agreed, giving a response rate of 85%.

There were slightly more males (58%) than females (42%) in the study population. The mean age was 56.1 years (SD = 9.4) with an age range of 40 to 83 years (Table 1). All subjects were first generation Bangladeshis. Only 6% (n = 10) of the study population lived alone. The average length of residence in the UK was 24.5 years, with a range from 54 years to less than 1 year. Seventy-five per cent (n = 50) of females had lived in the UK for 17 years or less while only one male had lived in the UK for this period of time.

Use of dental services

Only 20% of subjects claimed to be registered with a dentist yet 33% of subjects had visited the dentist in the last year. Twenty-five per cent of subjects had never visited the dentist. More females than males had never visited the dentist (P < 0.001), and females were less likely than males to feel that regular check-ups are important for a healthy mouth (P < 0.01). Seventy-three per cent of the study population experienced language difficulties in their general use of health services and more females (94%) than males (58%) experienced difficulties (P < 0.001)(Table 2). The majority of the sample (98%) spoke Sylheti as their first language. Sixty-eight per cent of subjects mentioned the need for advocates and/or interpreters to help overcome these difficulties. Thirty-three subjects (21%) specifically reported experiencing barriers in their use of dental services. The main barrier reported was language difficulties, then cost and fear. As an alternative to having advocates or interpreters present who could explain the treatment, evening appointments were praised so a family member could accompany the subject and interpret for them.

There was a symptom orientated view toward visiting the dentist with around half (46%) of the subjects attending because they were in pain and almost a quarter (24%) wanting new dentures. When asked whom they would approach to get a mouth ulcer or sore mouth checked 64% of subjects indicated that they would approach their general medical practitioner with only 9% mentioning the dentist.

Sixty-two subjects (39%) would like to learn more about oral healthcare. Sixty-one subjects (39%) reported using health education materials, mostly in the form of posters, although ten subjects (16%) specifically did not know what the material was about as they could not read English. When asked how the information could be improved the main suggestions were: translation into Bengali, less words and more pictures, videos and the use of group sessions with an interpreter.

Tobacco smoking habits

Tobacco smoking was practised by 33% of the sample. Only 4% of females smoked. The majority of smokers (64%) had started to smoke by the time they reached their twenty first birthday. Various cultural forms of smoking were reported such as bidi and hooka. Forty-two per cent of the population had never smoked and 88% of these were females. Seventy-one per cent of smokers also chewed paan.

Paan chewing habits

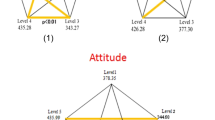

Seventy-eight per cent of the sample chewed paan. Of the subjects who chewed paan the most popular ingredients were betel leaf (99%), areca nut (98%) and lime (81%). Tobacco was added by 52% of those who used paan. It was added either on its own or as a component of zarda (processed tobacco). The habit was adopted as early as 6 years of age and as late as 56 with a mean age of 20.91 (SD = 11.45). However, 50% were chewing paan by the age of 17 years (fig. 1). More males began chewing paan by 15 years of age than females (P < 0.05). Paan was consumed lightly (one to three times daily) by 32% of chewers but 18 (11%) chewers were heavy users (chewed 8+ times a day). It was found that females chewed paan more frequently than males (fig. 2). The majority of subjects (76%) retained the paan in their buccal sulcus. The two sexes showed significant differences in their use of paan. Females are much more likely to use paan than males and add tobacco to their quid (P < 0.01). When frequency of chewing is looked at more females are heavy chewers and more males are light chewers (P < 0.001)(Table 2). Of those who had chewed paan more males (25%) than females (5%) had abandoned the habit (P < 0.01). Only 6% of the study population had never chewed paan.

Forty-three per cent of the study population did not know that paan chewing could be bad for health. More females (49%) than males (38%) were unaware of the possible harmful effects of paan chewing. Almost a quarter of subjects (23%) believed that it is good for dental health. The reasons cited were that it stops pain in the teeth and gums, and keeps teeth strong. Paan was also used to aid digestion and to keep the mouth fresh. For those subjects who believed paan was bad for health it was believed to be bad for the mouth and stomach and some subjects mentioned diabetes. Subjects who chewed paan eight times or more a day were more likely to believe that paan was good for health than those who either did not chew or chewed it less than eight times a day (P < 0.001). Fourteen per cent of the study population volunteered the fact that they were addicted to it.

Discussion

It was decided to recruit the sample from the waiting areas of general practitioner's surgeries. This was because, firstly, lack of a sampling frame prevents random sampling. Secondly, random sampling of ethnic minority groups by address or electoral register is not practical and very expensive in terms of time and labour.28 While sampling from electoral rolls has been used to identify South Asians for population studies,28,29 this method becomes inefficient if, as in this study, a relatively narrow age range is to be sampled. In addition to not reporting age, the completeness of electoral registers for ethnic minorities has also been questioned.31,32 Thirdly, the Local Research Ethics Committee expressed concern about researchers approaching subjects at home, their addresses having been obtained from general practitioners age/sex registers. They felt that only subjects who responded to a letter of invitation from their general practitioner could be approached. If this method was adopted the sample recruited would have been extremely limited and biased. Studies of Bangladeshi communities that have used bilingual questionnaires have obtained response rates in the range of 17–46%.33,34 These authors suggested that illiteracy was a major factor for the low response. While the present sample is not representative of the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets since only subjects who were visiting their general practitioner were approached, within Tower Hamlets consultancy rates for general medical practitioners are very high.35 Within a 1-month period 45% of Bangladeshis reported consulting their general practitioner. This rises in the older age groups (50–74 years) to 66% in women and 72% in men.15

A satisfactory response rate of 85% was achieved. By using a Sylheti speaking interviewer participants who were either illiterate or unable to speak English or Bengali were not excluded. Most Bangladeshis in Tower Hamlets speak Sylheti, a regional variant of Bengali that does not have a written form of its own. Bengali is the language of literacy yet only 16% of Bangladeshis living in Tower Hamlets can read or write it. MORI36 identified that Bangladeshi residents were linguistically the most disadvantaged ethnic group surveyed within ELCHA: only 27% reported that they could read English 'very' or 'fairly well'.

The results show that use of dental services among medical service users was low with only 33% having visited the dentist in the last year. Thirteen per cent of respondents had made emergency use of dental services, thus only 20% were regular attenders. A variety of barriers have been proposed to explain the low use of dental services including language difficulties, a symptom oriented view of service use and domestic isolation of women.7,37 The findings reported here suggest the need for further research on this issue, because although the reported use of dental services was low this was not the case with respect to medical services.

Oral screening for precancerous or cancerous lesions in general dental practice may be of limited use in Bangladeshi medical service users. Sixty-four per cent of the study population would visit their doctor if they had a persistent mouth ulcer or mouth problem as opposed to 9% a dentist, although a different response may have resulted if the sample had been obtained from another source. Hoare et al38 have shown in Asian women that the concept of screening well women for asymptomatic disease was not well understood. Rudat15 showed that among all ethnic groups Bangladeshis were the least likely to have had any type of cancer screening, only 28% of Bangladeshi women reported having had a cervical smear. He proposed lack of information as one factor in this lack of uptake.

The results show that paan chewing is widespread in this community and that many respondents started this habit before the age of 15 years. The findings show similar trends to those reported in the literature.15,16,17 These are that women are more likely to chew paan, are also more likely to add tobacco to the quid and that this habit starts in the teens. It appears that in Tower Hamlets Bangladeshis report using paan and tobacco less than the communities in Birmingham and West Yorkshire. The HEA survey drew its Bangladeshi sample from Tower Hamlets. Of the women in West Yorkshire 95% reported chewing paan, of which 89% added tobacco.16 In Birmingham, 96% of women and 92% of men reported chewing paan, of which 81% of women and 37% of men added tobacco to their quid.17 In this study, 86% of women and 71% of men reported this behaviour, of which 64% of women and 42% of men chewed tobacco. Rudat15 reported that 50% of all his Bangladeshi sample chewed paan and 28% added tobacco, but that in the 50–74 year age group 76% of women and 62% of men chew paan. His figures for adding tobacco are 58% and 31% respectively.

An important finding from this study is that of all those who had at any time chewed paan 25% of males and 5% of women had successfully given it up. This compares with 9% of males and 4% of females reported by Bedi & Gilthorpe.17 Unfortunately no questions were asked as to the reason for stopping the habit and this should be an area of further research. It may be that as this sample was obtained from doctors' waiting rooms they had come into contact with health professionals who had advised them of the health risks associated with this habit. However, a similar awareness of health risks between the two populations was noted, 54% in the present study were aware that paan chewing was bad for health compared with the 52% found by Bedi & Gilthorpe.39

Regarding smoking behaviours, all studies report similar and significant differences between the sexes. This study found that 53% of males smoked which is similar to the 58% reported by Bedi and Gilthorpe.17 Seventy-one per cent of smokers also chewed paan. It is recognised that the combined habits of paan chewing and smoking carry increased risks of oral cancer12 so health messages aimed at males may need to be modified.

Charlton40 has suggested health promotion strategies in relation to paan chewing and tobacco chewing. This includes, firstly, providing information about the health risks involved and, secondly, social support to facilitate the decision to avoid the oral use of tobacco in any form. Thirdly, to encourage screening and mouth self examinations and, fourthly, to try and improve the social environment. Bedi and Gilthorpe39 have suggested the 'ethnic mass media', particularly the radio as a promising mode of communication for oral health promotion. This study suggested that video or group sessions be used for delivering health messages. Sylheti is the dialect used by 98% of the sample on a day-to-day basis, it has no written form and Hossain41 found illiteracy levels in Bengali of 44%. This rose to 82% in those aged 60 and over. The use of videos as the preferred medium of communication has also been identified by Kwan et al.42 It is also important that healthcare professionals are aware of the health risks associated with paan chewing and of the signs and symptoms of oral cancer and precancer. Islam et al.43 found paan chewing has deep seated cultural roots and the selling of paan ingredients plays an important role in the economics of the Bangladeshi retail trade in Tower Hamlets. Health promotion interventions will need to be sensitively tailored.

Conclusion

Considerable barriers will need to be overcome if dental practices are to be the site for oral cancer screening and oral health promotion for this group of Bangladeshi medical service users living in Tower Hamlets. Further research should explore the views of the wider Bangladeshi community on the perceived benefits of oral screening and the role of the general dental practitioner in this. Paan chewing is widespread in this group. There are sex differences in tobacco and paan use and in behaviour and attitudes about use of dental services in this Bangladeshi sample.

References

Johnson N W, Warnakulasuriya K A . Epidemiology and aetiology of oral cancer in the United Kingdom. Community Dent Health 1993; 10 Suppl 1: 13–29.

Speight P M, Morgan P R . The natural history and pathology of oral cancer and precancer. Community Dent Health 1993; 10 Suppl 1: 31–41.

Gupta P C, Mehta F S, Daftary D K, et al. Incidence rates of oral cancer and natural history of oral precancerous lesions in a 10-year follow-up study of Indian villagers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1980; 8: 283–333.

Boyle P, Macfarlane G J, Chiesa F, et al. European School of Oncology Advisory report to the European Commission for the Europe Against Cancer Programme: oral carcinogenesis in Europe. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1995; 31B: 75–85.

UK Working Group on Screening for Oral Cancer. Conclusions and recommendations. Community Dent Health 1993; 10 Suppl 1: 87–89.

Selikowitz H S, Holst D . Dental health behaviour in a migrant perspective: use of dental services of Pakistani immigrants in Norway. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986; 14: 297–301.

Williams S A, Gelbier S . Access to dental health? An ethnic minority perspective of the dental services. Health Educ J 1988; 47: 167–170.

Mattin D, Smith J M . The oral health status, dental needs and factors affecting utilisation of dental services in Asians aged 55 years and over, resident in Southampton. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 369–372.

Cancer Research Campaign. Oral cancer Factsheet 14.1. London: Cancer Research Campaign, 1993.

Sakai O, Tsutsui T, Watanabe T, Warnakulasuriya S . Oral health in Asia. Oral Dis 1995; 1: 98–99.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monograph 37: tobacco habits other than smoking; betel-quid and areca nut chewing, and some related nitrosamines. Lyon: IARC, 1985.

Thomas S, Wilson A A . Quantitative evaluation of the role of betel quid in oral carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1993; 29B: 265–271.

Van Wyk C W, Stander I, Padaychee A, Grobler-Rabie A F . The areca nut chewing habit and oral squamous cell carcinoma in South African Indians. S Afr Med J 1993; 83: 425–429.

Wilson D F, Grappin G, Miquel J L . Traditional, cultural, and ritual practices involving the teeth and orofacial soft tissues. In Prabhu S R, Wilson D F, Daftary D K, Johnson N W (eds). Oral diseases in the Tropics. pp 91–120. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Rudat K . Black and minority ethnic groups in England, health and lifestyle. London: Health Education Authority, 1994.

Summers R A, Williams S A, Curzon M E J . The use of tobacco and betel quid ('pan') among Bangladeshi women in West Yorkshire. Community Dent Health 1994; 11: 12–16.

Bedi R, Gilthorpe M S . The prevalence of betel-quid and tobacco chewing among the Bangladeshi community resident in a United Kingdom area of multiple deprivation. Primary Dent Care 1995; 2: 39–42.

Chaturvedi N, McKeigue P M . Methods for epidemiological surveys of ethnic minority groups. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994; 48(2): 107–111.

Donaldson L J . Health and social status of elderly Asians: a community survey. BMJ 1986; 293: 1079–1086.

Haines A P, Booroff A, Goldenberg E et al. Blood pressure, smoking, obeisty and alcohol consumption in black and white patients in general practice. J Hum Hypertens 1987; 1: 39–46.

Gillam S J, Jarman B, White P, Law R . Ethnic differences in consultation rates in urban general practice. BMJ 1989; 299: 953–957.

McKeigue P M, Shah B, Marmot M G . Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Lancet 1991; 337: 382–386.

Bradley S M, Freidman E H . Cervical cytology screening: a comparison of uptake among 'Asian' and 'non-Asian' women in Oldham. J Public Health Med 1993; 15: 46–51.

Chaturvedi N, McKeigue P M, Marmot M G . Resting and ambulatory blood pressure differences in Afro-Caribbeans and Europeans. Hypertension 1993; 22: 90–96.

Ritch A E, Ehtisham M, Guthrie S et al. Ethnic influence on health and dependency of elderly inner city residents. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1996; 30: 215–220.

Bone M . Registration with general medical practitioners in inner London: a survey carried out on behalf of the Department of Health and Social Security. London: HMSO, 1984.

Speight P M, Zakrezewska J, Downer M C . Screening for oral cancer and precancer. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1992; 28B: 45–48.

Ecob R, Williams R Sampling Asian minorities to assess health and welfare. J Epidemiol Community Health 1991: 45; 93–101.

McFarland E, Dalton M, Walsh D . Ethnic minority needs and service delivery: the barriers to access in a Glasgow inner-city area. New Community 1989; 15: 405–415.

Williams R . Health and length of residence among South Asians in Glasgow: a study controlling for age. J Public Health Med 1993; 15: 52–60.

Foster K . The electoral register as a sampling frame. Survey Methodology Bull 1993; 33: 1–7.

Jacobson B . Public health in inner London. BMJ 1992; 305: 1344–1347.

Ahmed S, Rahman A, Hull S . Use of betel quid and cigarettes among Bangladeshi patients in an inner-city practice: prevalence and knowledge of health effects. Br J Gen Pract 1997; 47: 431–434.

MacCarthy B, Craissati J . Ethnic differences in response to adversity. A community sample of Bangladeshis and their indigenous neighbours. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1989; 24: 196–201.

Ali D, Begum R A . Health and social circumstances of the elderly Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets: a background report. London: Department of Health Care of the Elderly, The Royal London Hospital Medical College, 1991.

MORI. East London Health. London: City & East London Family Health Services Authority, 1993.

Taylor W, Gelbier S . Dietary patterns, dental awareness and dental caries in the Asian community. Dent Health 1983; 22: 5–6.

Hoare T A, Johnson C M, Gorton R, Alberg C . Reasons for non-attendance for breast screening by Asian women. Health Educ J 1992; 51: 157–161.

Bedi R, Gilthorpe M S . Betel-quid and tobacco chewing among the Bangladeshi community in areas of multiple deprivation. In Bedi R, Jones P, (eds). Betel-quid and tobacco chewing among the Bangladeshi community in the United Kingdom. pp 37–52. London: Centre for Transcultural Oral Health, 1995.

Charlton A . Health promotion strategies in relation to betel-quid and tobacco chewing. In Bedi R, Jones P, (eds). Betel-quid and tobacco chewing among the Bangladeshi community in the United Kingdom. pp 27–35. London: Centre for Transcultural Oral Health, 1995.

Hossain N . Language and communication survey. London: Tower Hamlets Department of Public Health Medicine, 1991.

Kwan S Y L, Williams S A, Duggal M S . An assessment of the appropriateness of dental health education materials for ethnic minorities. Int Dent J 1996; 46 Suppl 1: 277–285.

Islam S, Croucher R, O'Farrell M . Paan chewing in Tower Hamlets, London. London: Tower Hamlets Healthcare NHS Trust/Department of Dental Public Health, The London Hospital Medical College, 1996.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pearson, N., Croucher, R., Marcenes, W. et al. Dental service use and the implications for oral cancer screening in a sample of Bangladeshi adult medical care users living in Tower Hamlets, UK. Br Dent J 186, 517–521 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800156

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800156

This article is cited by

-

Knowledge, attitudes and practices of South Asian immigrants in developed countries regarding oral cancer: an integrative review

BMC Cancer (2020)

-

Ethnic differences in oral health and use of dental services: cross-sectional study using the 2009 Adult Dental Health Survey

BMC Oral Health (2017)

-

Factors associated with dental and medical care attendance in UK resident Yemeni khat chewers: a cross sectional study

BMC Public Health (2012)

-

Oral cancer screening in the Bangladeshi community of Tower Hamlets: a social model

British Journal of Cancer (2009)

-

Physiognomy and teeth: An ethnographic study among young and middle-aged Hong Kong adults

British Dental Journal (2002)