Abstract

This paper examines the way patient satisfaction is perceived in the dental literature. The majority of studies carried out since the early 1980s concentrate on patient perceptions of various service quality attributes and the role that sociodemographic variables play in determining satisfaction. Recent work concerning attribution theory suggests that two concepts, duty and culpability, may be central to explaining this process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In 1995, Sir David Mason wrote about the challenges and opportunities facing the dental profession and identified the 'consumer revolution' as being one of the major trends currently shaping general dental practice in the UK:1

'More people want more say about their health and health services, the best care for themselves and their families and choice in that care. For the NHS the result has been a profound shift in emphasis from service providers to patients, the full effects of which have yet to be realised'.

One of these effects is the growing impact that patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction will have on the business success of dental practice. Satisfying patients should be a key task for all dental providers — 46% of dentists surveyed in one study2 indicated that dissatisfaction with the way patients were handled by their dentist was 'very often' or 'fairly often' seen as the reason for switching dentists. In a more recent study those patients surveyed cited 'unhappy with dentist' as being the main reason for changing dentists.3

As with healthcare in general, patient satisfaction has also been shown to influence compliance and, in turn, treatment quality.4 This is relevant to all aspects of dentistry but is particularly so in those situations where patient cooperation is vital, such as orthodontic treatment and periodontal therapy.

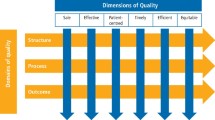

Although a number of patient satisfaction studies were conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, the social, business and professional environments have changed dramatically since then. This review therefore concentrates only on studies conducted since 1980 (Table 1).3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 All of these studies, with a few exceptions, deal with a generic list of five issues that affect patient satisfaction with dental care: 1. Technical competence 2. Interpersonal factors 3. Convenience 4. Costs and 5. Facilities. These characteristics are equivalent to the service quality dimensions described by Parasuraman and Berry,49 and discussed in Part 1, namely reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy and tangibles. As was noted then, the manner in which the patient perceives these attributes is only one determinant of satisfaction and yet a very common assumption made in the dental literature is that the sum of a patient's perceptions equates with, and is therefore a measure of, his or her overall satisfaction. Two well-known survey instruments, the Dental Satisfaction Questionnaire (DSQ),9 and the Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale (DVSS),13 both assess patient perceptions of various dimensions of care while ignoring the potential roles of a number of other influences, particularly disconfirmation and attribution, which are considered to be extremely important in the wider marketing and healthcare literatures. The DVSS does recognise affective, cognitive and behavioural influences and does seek out patient's views on specific dental encounters, unlike the DSQ which concentrates on cognitive factors and looks only at dentists in general.

Expectations

A small number of recent studies have examined the fulfilment of expectations by comparing patients' views on ideal and actual behaviour of dentists.3,4 'Ideal behaviour' is equivalent to the 'desired service' component of Zeithaml and Bitner's 'zone of tolerance' concept discussed in Part 1.50 These studies clearly show the gap that exists between the sort of service patients hope to receive and the service they actually receive. Lahti et al., for example, reported that:40

'The discrepancies found (between ideal and actual dentist behaviour) fell mostly into the area of the 'communicative and informative' factor, ie the dentists often did not give information about preventive procedures, did not ask if the patient wanted local anaesthesia, did not ask about the special problems of the patient and did not ask how the patient felt. Other discrepancies included not admitting if the procedure was too difficult and not washing hands'.

The authors offer the following explanation:

'...as the procedures are so common and clear to dentists, they do not see the importance of talking about them and explaining them to their patients. One example is the fact that, even though most dentists certainly wash their hands before treatment, they do not see that it might be important for the patient to see them doing so'.

It is clear from these studies that disconfirmation does take place, although the nature and existence of the relationship between disconfirmation and overall satisfaction has not been tested — it is therefore not yet known whether unfulfilled expectations will automatically result in patient dissatisfaction. As for factors that contribute to the formation of expectations, Clow et al. found that patient image of the dentist, tangible cues, situational factors and patient satisfaction with previous encounters appear to have the greatest influence on expectations whereas marketing variables such as price and advertising appear to have no effect.38 The authors observed that knowledge of patient expectations is important, in that it helps dentists to change both the service delivery process and the service outcome to meet expectations, and to actively manage patient expectations to ensure that they coincide with the service to be provided.

While such recommendations appear to make considerable sense, research, on the other hand, points to the substantial gap that exists between patients' expectations and dentists' understanding of those expectations. Burke and Croucher, for example, asked patients to evaluate sixteen criteria of 'good practice'.42 Eight criteria were proposed by dentists and eight by patients and of these the three ranked highest by patients were: 1. Explanation of procedures 2. Sterilisation/hygiene and 3. Dentists skills (all criteria proposed by patients), while the three lowest ranked were: 1. Up-to-date equipment 2. Pleasant decor and 3. Good practice image (all criteria proposed by dentists). Similar findings are reported by Gerbert and Bleecker:37 69% of patients surveyed indicated that performing procedures efficiently is extremely important compared to 36% of dentists; 47% of patients indicated that 'explaining infection control' was extremely important, compared to 12% of dentists. These, and other, similar, studies suggest that dentists believe they know what patients should want, rather than finding out what they do want.4,19

Perceptions

As was noted earlier most studies on dental patient satisfaction actually explore patient perceptions of various service quality attributes. The following section attempts to identify the relative importance of these factors in patient evaluations of dental practice.

Technical competence of the dentist. This factor is often cited as being a key determinant of dental satisfaction with many studies placing it at, or near the top, of contributory factors. However, it has been observed that people, in general, find it difficult to evaluate the technical quality of a service accurately and so form impressions of the service from a number of other cues that may not be apparent to the provider.50 In a study comparing dentist and patient assessments of dental restoration quality Abrams et al.51 concluded that:

'Simply practicising dentistry with a high degree of technical expertise will not necessarily convince the patient that he has received high quality dental care. Other less technical aspects of dental treatment are recognised as being barometers of quality of dental treatment. Practitioners should not lose sight of the human and psychological aspects of care, and keep in mind that they are integral components of quality in dental treatment'.

Interpersonal factors. If patients do experience difficulty evaluating 'hard', technical, aspects of dentistry what evidence is there to suggest that they judge the dentist using 'softer', less tangible, characteristics? Corah and O'Shea pointed out that evaluations of technical competence (measured by asking patients to respond to statements such as: 'The dentist was thorough in doing the procedure' and 'I was satisfied with what the dentist did') are most likely based on interpersonal factors such as 'communication' 'caring' and 'information-giving'.13 Unlike technical quality, these are attributes upon which patients are fully capable of passing judgement and are consistently reported as being among the most important traits dentists should possess. For example, Holt and McHugh found the most important factor influencing dentist/practice loyalty to be 'care and attention' rated as very important by 90% of respondents, while three other, related, factors: 'pain control', 'dentist puts you at ease' and 'safety conscious' were each rated as being very important by 73% of respondents.3 Chakraborty et al. used conjoint analysis to assess patient preferences and to examine the trade-off that occurs between various attributes.35 Once again, preferred dentists were those who: 'respond to their pain, discuss their fears, and help to overcome them'. Communication skills have also been shown to be important in limiting patient dissatisfaction, so preventing liability claims.52 Barnes found the dentist's willingness to talk to patients and sensitivity expressed toward children to be important criteria in assessment.15 Earlier studies also report on the importance of communication and information-giving in fostering patient satisfaction.6,11

On the other hand, a study conducted by Goedhart et al.,43 in which the views of regular attenders in Holland were examined, found that communicative skills of dental personnel were relatively undervalued compared to various aspects of treatment quality. The authors noted, though, that with regular attenders communication between dentist and patient is likely to be already established and they point to evidence showing that in a group of non-attenders the communicative skills of dental personnel are seen as being more important.53

Findings in relation to the remaining three commonly-surveyed attributes are mixed.

Convenience. Some studies have explored the different patient responses to hospital clinics, neighbourhood health centres, private practices, and shopping mall practices26 with patients finding favour, for example, with convenience-oriented characteristics such as 'after hours' clinics.44 However, convenience factors do not appear to carry as much weight with patients as, say, communication factors, Holt and McHugh, for example found that three of the four least important 'decision-forming' factors for patients were opening hours, waiting time and time spent with the dentist.3 Janda et al. concluded that dentists should not emphasise convenience-oriented attributes such as location and parking facilities but should focus on characteristics of the core service such as quality of service, professional competence, personality and the attitudes of the dentist.45

Costs. While costs of treatment are often seen to be high by patients,12 fees in themselves do not appear to be as big a problem with patients as do communication about fees. Kress and Silversin,21 for example, found the two lowest-rated items in their survey to be 'Knowing in advance what the fee will be' and 'Believing that the fees are appropriate'. Barnes also found cost to be the least important of the considerations involved in selecting a dentist and observed that the real value of cost is that it is used by patients as an indicator of quality:15

'In this context prices are simply interpreted as being fair by a patient who has perceived the quality of care to be high. The implication is that those patients who think the fees are too high are also dissatisfied with the quality of care'.

In a study of patients' views about preventive dental care Croucher noted that patients' ultimate fear was of exploitation, with respondents being in ignorance of the overall level of charge, angry about the way the final bill was presented and confused about whether the completion of a course of treatment carried with it any form of guaranteed dental fitness for the next six months.54

Facilities. Although not considered to be as important as other factors in determing patient satisfaction the clinic facilities, for example the neatness, comfort of seating, magazine selection, background music etc have been shown to influence patients.14

Patient factors and satisfaction

Many of the studies presented in Table 1 also look for relationships between perceptions of care and various independent variables, in particular, sociodemographic factors. Findings however, tend to be contradictory, no doubt because the factors do not operate in isolation but interplay with each other.

Age. In a study looking specifically at satisfaction of the older patient with dental care Stege found that patients over the age of 60 years tended to be more satisfied with their dental care than younger patients, but were less satisfied with the communication process than younger patients.20 Lahti et al., on the other hand, found older patients to be less satisfied and explained their findings by the fact that the oral health status of the younger patient is usually better than that of older people, which may lead to better experiences.46

Gender. Gopalkrishna and Mummalaneni found that women expressed greater levels of satisfaction with dental care than men,36 attributing this finding to their greater exposure to dental services which would likely moderate their expectations, which in turn, are more likely to be met.

Economic status. Compared to 'non-poor', people from low income groups have been shown to hold very different attitudes about, and satisfaction with, healthcare, showing more negative perceptions of care and lower intentions to seek care.55 Golletz et al. observed similar findings in reviewing satisfaction with dental care among a low income population.39 The study also revealed that people with poor self-rated dental health consistently rate their satisfaction with dental care lower than those with higher ratings of their own dental health.

Previous dental experiences. A number of studies report that satisfaction with dental care is heavily influenced by previous experiences46,56 and that dentists who had consistently performed well in the past could weather an occasional poor performance because patients attributed any shortcoming to 'uncontrollable or sporadic elements'.38

Regular versus irregular attenders. There is generally held to be a positive correlation between the degree of use of dental care and satisfaction with that care12 and as noted earlier Goedhart et al. observed differences between the views of regular and non-attenders.43 Other studies however, for example Lahti et al., found no differences.46

Dental anxiety. It has been shown that dentally anxious individuals are more dissatisfied with dental care than their non-anxious counterparts.57,58

Directions for future research

This review shows that dental patient satisfaction is the result of an extremely complex process and that we are a considerable way from unravelling the myriad of antecedent factors that result in expressions of satisfaction and dissatisfaction. In the past, research has concentrated on identifying two things — firstly, those practice attributes that are the most influential in determining satisfaction and secondly, how different patient groups react to these various attributes. Patient 'criticisms' of dental providers are, however, almost universally coupled in these surveys with a high overall satisfaction rate. This suggests that a patient may have a bad experience with the dentist but may nevertheless express overall satisfaction. Attribution theory may be able to help explain this apparent contradiction in that it deals with how blame is apportioned if things do go 'wrong':59

'When service users believe that they are being asked to evaluate a service their responses appear to be guided by beliefs about what the service 'should' and 'should not' do ('duty') and whether or not the service is to 'blame' if it does things it shouldn't or fails to do things it should ('culpability'). High satisfaction ratings may not indicate that people have had good or even average experiences in relation to the service; rather, expressions of satisfaction may often reflect attitudes such as 'they are doing the best they can' or 'well it's not really their job...' '

Thus, it is possible that positive or negative experiences (the perceptions of service) only correlate with positive or negative evaluations of the service when the concepts of duty and culpability are taken into account. It may be the case that many of the apparent 'criticisms' found in dental satisfaction surveys might actually be reports only of negative experiences and not actual evaluations of the services at all — hence high overall satisfaction rates. Some evidence for this can be found in the recent observation that a substantial proportion of patients claiming to have had painful or distressing experiences at the dentist are just as likely to have a positive attitude to dentistry as those who have not.60

It is clear that future research must examine the role of attribution in dental practice, if more light is to be shed on the process by which positive or negative experiences are subsequently translated into positive or negative evaluations of the dental provider. More needs to be known about patient expectations, not only in terms of the desired service, but also the minimum acceptable or adequate service. What do patients see as comprising the 'duty' of the dental provider? What is it, in the eyes of the patient, that the service should and should not do? How do patients' assign blame when things go wrong — the 'culpability' element of attribution. It may be that attribution is a filter through which all negative dental experiences must flow before becoming service evaluations and hence expressions of dissatisfaction.

References

Mason D . General dental practice — challenges and opportunities: a personal view. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 350–354.

O'Shea R, Corah N, Ayer W . Why patients change dentists: practitioners' views. J Am Dent Assoc 1986; 112: 851–854.

Holt V, McHugh K . Factors influencing patient loyalty to dentist and dental practice. Br Dent J 1997; 183: 365–370.

Zimmerman R . The dental appointment and patient behavior. Differences in patient and practitioner preferences, patient satisfaction, and adherence. Med Care 1988; 26: 403–414.

Estabrook B, Zapka J, Lubin H . Consumer perceptions of dental care in the health services program of an educational institution. J Am Dent Assoc 1980; 100: 540–543.

Garfunkel E . The consumer speaks: How patients select and how much they know about dental health care personnel. J Prosthet Dent 1980; 43: 380–384.

Strauss R, Claris S, Lindahl R, Parker P . Patients' attitudes toward quality assurance in dentistry. J Am Coll Dent 1980; 47: 101–109.

van Groenestijn M, Maas-de Waal C, Mileman P . The ideal dentist. Soc Sci Med 1980; 14: 533–540.

Davies A, Ware J . Measuring patient satisfaction with dental care. Soc Sci Med 1981; 15: 751–760.

Murray B, Kaplan A Patient satisfaction in 14 private dental practices. IDAR Abstract No. 892. J Dent Res 1981; 60: 532.

Murtomaa H, Masalin K . Public image of dentists and dental visits in Finland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1982; 10: 133–136.

Alvesalo I, Uusi-Heikkilä Y . Use of services, care-seeking behavior and satisfaction among university dental clinic patients in Finland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1984; 12: 297–302.

Corah N, O'Shea R . Development of a patient measure of satisfaction with the dentist: The dental visit satisfaction scale. J Behav Med 1984; 7: 367–373.

Andrus D, Buchheister J . Major factors affecting dental consumer satisfaction. Health Market Q 1985; 3: 57–68.

Barnes N . Open wide: an examination of how patients select and evaluate their dentist. Health Market Q 1985; 3: 49–56.

Chapko M, Bergner M, Green K, Beach B, Milgrom P, Skalabrin N . Development and validation of a measure of dental patient satisfaction. Med Care 1985; 23: 39–49.

Rankin J, Harris M . Patients' preferences for dentists behaviors. J Am Dent Assoc 1985; 110: 323–327.

Barnes N, Mowatt D . An examination of patient attitudes and their implications for dental service marketing. J Health Care Market 1986; 6: 60–63.

Rao C, Rosenberg L . Consumer behavior analysis for improved dental services marketing. Health Market Q 1986; 3: 83–96.

Stege P, Handelman S, Baric J, Espeland M . Satisfaction of the older patient with dental care. Gerodontics 1986; 2: 171–174.

Kress G, Silversin J . The role of dental practice characteristics in patient satisfaction. Gen Dent 1987; 35: 454–457.

Kress G . Improving patient satisfaction. Int Dent J 1987; 37: 117–122.

Corah N, O'Shea R, Bissell G, Thines T, Mendola P . The dentist-patient relationship: Perceived dentist behaviors that reduce patient anxiety and increase satisfaction. J Am Dent Assoc 1988; 116: 73–76.

Crane F, Lynch J . Consumer selection of physicians and dentists: An examination of choice criteria and cue usage. J Health Care Market 1988; 8: 16–19.

Kressel N, Haycock R . Consumer selection and evaluation of dentists. Health Market Q 1988; 5: 15–31.

Handelman S, Fan-Hsu J, Proskin H . Patient satisfaction in four types of dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc 1990; 121: 624–630.

Hill C, Garner S, Hanna M . What dental professionals should know about dental consumers. Health Market Q 1990; 8: 45–57.

Johnson J, Scheetz J, Shugars D, Damiano P, Schweitzer S . Development and validation of a consumer quality assessment instrument for dentistry. J Dent Educ 1990; 54: 644–652.

Williams S, Calnan M . Convergence and divergence: Assessing criteria of consumer satisfaction across general practice, dental and hospital care settings. Soc Sci Med 1991; 33: 707–716.

Arnbjerg D, Söderfeldt B, Palmqvist S . Factors determining satisfaction with dental care. Community Dent Health 1992; 9: 295–300.

Badner V, Bazdekis T, Richards C . Patient satisfaction with dental care in a municipal hospital. Spec Care Dent 1992; 12: 9–14.

Lahti S, Tuutti H, Hausen H, Kääriäinen R . Dentist and patient opinions about the ideal dentist and patient — developing a compact questionnaire. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1992; 20: 229–234.

Stouthard M, Hartman C, Hoogstraten J . Development of a Dutch version of the dental visit satisfaction scale. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1992; 20: 351–353.

Wunder G . Things your most satisfied patients won't tell you. J Am Dent Assoc 1992; 123: 129–132.

Chakraborty G, Gaeth G, Cunningham M . Understanding consumers' preferences for dental service. J Health Care Market 1993; 13: 48–58.

Gopalakrishna P, Mummalaneni V . Influencing satisfaction for dental services. J Health Care Market 1993; 13: 16–22.

Gerbert B, Bleecker T, Saub E . Dentists and the patients who love them: professional and patient views of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 1994; 125: 265–272.

Clow K, Fischer A, O'Bryan D . Patient expectations of dental services. J Health Care Market 1995; 15: 23–31.

Golletz, Milgrom P, Manci L . Dental care satisfaction: The reliability and validity of the DSQ in a low-income population. J Public Health Dentist 1995; 55: 210–217.

Lahti S, Tuuti H, Hausen H, Kääriäinen R . Comparison of ideal and actual behavior of patients and dentists during dental treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1995; 23: 374–378.

Lewis J, Campain A, Wright F . Adult dental services in Melbourne: Accessibilty and client satisfaction. Public Health and Epidemiology Research Unit, School of Dental Science, University of Melbourne, 1995.

Burke L, Croucher R . Criteria of good dental practice generated by general dental practitioners and patients. Int Dent J 1996; 46: 3–9.

Goedhart H, Eijkman M, ter Horst G . Quality of dental care: the view of regular attenders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 28–31.

Handelman S, Jensen O, Jensen P, Black P . Patient satisfaction in a regular and after-hours dental clinic. Spec Care Dent 1996; 16: 194–198.

Janda S, Wang Z, Rao C . Matching dental offerings with expectations. J Health Care Market 1996; 16: 38–44.

Lahti S, Hausen H, Kääriäinen R . Patients'expectations of an ideal dentist and their views concerning the dentist they visited: Do the views conform to the expectations and what determines how well they conform?. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 240–244.

Lahti S, Verkasalo M, Hausen H, Tuutti H . Ideal role behaviors seen by dentists and patients themselves and by their role partners: Do they differ?. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 245–248.

Unell L, Söderfeldt B, Halling A, Paulander J, Birkhed D . Equality in satisfaction, perceived need, and utilization of dental care in a 50-year old Swedish population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 191–195.

Parasuraman A, Berry L . SERVQUAL: a multiple item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J Retailing 1988; 1: 12–40.

Zeithaml V, Bitner M . Services marketing. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

Abrams R, Ayers C, Vogt Petterson M . Quality assessment of dental restorations: a comparison by dentists and patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986; 14: 317–319.

Mellor A, Milgrom P . Dentists' attitudes toward frustrating patient visits: relationship to satisfaction and malpractice complaints. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1995; 23: 15–19.

Eijkman M, Visser A . Patientenvoorlichting en tandarts (Patient Education and Dentist). Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema, 1987.

Croucher R . The performance gap. Patients' views about dental care and the prevention of periodontal disease. London: Health Education Authority, 1991, Research Report No. 23.

Curbow B . Health care and the poor: psychological implications of restrictive policies. Health Psychol 1986; 5: 375–391.

Liddell A, Locker D . Dental visit satisfaction in a group of adults aged 50 years and over. J Behav Med 1992; 15: 415–427.

Locker D, Liddell A . Correlates of dental anxiety among older adults. J Dent Res 1991; 70: 198–203.

Locker D, Shapiro D, Liddell A . Negative dental experiences and their relationship to dental anxiety. Community Dent Health 1996; 13: 86–92.

Williams B, Healy D . The meaning of patient satisfaction: An explanation of high reported levels. Soc Sci Med In press.

Rice A, Liddell. Determinants of positive and negative attitudes toward dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc 1998; 64: 213–218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newsome, P., Wright, G. A review of patient satisfaction: 2. Dental patient satisfaction: an appraisal of recent literature. Br Dent J 186, 166–170 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800053

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800053

This article is cited by

-

Minimum intervention oral healthcare for people with dental phobia: a patient management pathway

British Dental Journal (2020)