Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objectives:

To present a rare but severe complication of intermittent catheterization.

Setting:

Paraplegic centre in Switzerland.

Method and results:

A 52-year-old man presenting with fever and septicaemia was diagnosed with a perineal abscess due to a bulbar urethral lesion caused by acute false passage during intermittent catheterization.

Conclusion:

Especially in patients with a history of urethral strictures performing intermittent catheterization, the possibility of perineal abscess formation should be taken into account when treating such a patient with fever of unknown origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord lesions are commonly associated with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Intermittent catheterization is the gold standard for bladder evacuation in these patients today.1 It is regarded as a safe procedure with a low complication rate. We report a severe complication caused by this technique.

Case report

In May 2007, a 52-year-old man with post-traumatic paraplegia sub-L2 (ASIA D) presented to our emergency room with fever and suprapubic pain since 3 days. Because of a neurogenic bladder dysfunction, he performed intermittent self-catheterization using hydrophilic catheters four times a day since 1991. Within the last week, catheterization had become increasingly difficult.

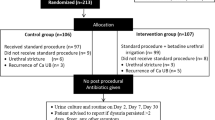

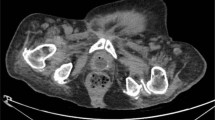

Medical history revealed that he underwent endoscopic urethrotomy for urethral strictures in 1995 and 1998. General examination was normal. On digital rectal examination, however, the prostate was tender and the examination was painful. On transrectal ultrasound, no signs of prostatic abscess formation were detected. Laboratory tests demonstrated an acute severe inflammation. Therefore, a prostatitis was diagnosed and antibiotic treatment was initiated. Primarily, the general state of the patient improved and the inflammation parameters decreased. On day 4 after admission, however, fever and perineal pain recurred, and the patient developed signs of septicaemia. Physical examination revealed a penile oedema. On computerized tomography (CT) scan, a large liquid mass in the perineum was detected, resembling a massive perineal abscess (Figures 1a and b).

Therefore, a perineal incision with drainage of the abscess was performed. Postoperative course was uneventful.

After recovery, a rectal or colonic fistula was ruled out by rectoscopy and colonoscopy. Retrograde urethrography demonstrated a bulbar urethral lesion with extravasation into the perineum, which was treated by insertion of a catheter (Figure 2).

At the most recent follow-up examination, 4 months after surgery, the patient could perform intermittent catheterization without any problem. On urethrography, a residual lesion could be ruled out.

Discussion

Urinary tract infections and urethral strictures are the most common complications of intermittent catheterization, the latter occurring exclusively in male patients. Especially during the early rehabilitation phase, when patients are instructed on how to perform intermittent catheterization acute urethral false passages are possible.2 Urethral strictures seem to be related to previous urethral lesions. Günther et al.1 demonstrated that a history of indwelling catheters or urethral lesions is correlated with a higher incidence of urethral strictures in men performing intermittent catheterization. Thus, urethral false passages might cause urethral strictures, which in turn are associated with a higher risk of urethral false passages. The patient described here suffered from recurrent urethral strictures. Therefore, he had an elevated risk for acute urethral false passages.

Perineal abscess formation is a rare condition. Most of them are considered as being idiopathic.3 They can be associated with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, like M Crohn3 or tuberculosis. Spontaneous or iatrogenic perforation of the urethra, however, for example during prostatic urethroplasty4 or urethral fistula/diverticula may also lead to abscess formation. Abscess formation as a complication of intermittent catheterization has only once been described previously.5 In contrast to the other case report, the abscess in our patient was not visible during physical examination already. If the diagnosis is not as obvious, these abscesses may well be missed by standard clinical evaluation. In our case, we were not able to diagnose the abscess by perineal or transrectal ultrasound during initial examination. It was merely visible at a CT scan. Thus, in our eyes, a CT scan or a magnetic resonance imaging is the method of choice for diagnostic evaluation, as it can demonstrate the exact localization and the extension of the process.

Immediate intervention with drainage of the abscess is mandatory. Although percutaneous drainage has been described,4 due to the extent of the abscess, we decided to perform surgical incision and drainage.

Further diagnostic procedures to clarify the aetiology of the abscess formation should be postponed until it is sufficiently treated. If a urethral lesion is suspected, we suggest performing urethrography instead of cystoscopy to avoid further urethral damage.

Conclusion

Abscess formation following acute false passage of a urethral catheter is a rare but severe complication of intermittent catheterization. If abscess formation is not clearly visible on physical examination, as it was the case in the previously reported case, diagnosis may be delayed as the symptoms are not specific and the condition is extremely rare. Especially in patients with a history of urethral strictures performing intermittent catheterization, the possibility of perineal abscess formation due to an acute false urethral passage should be taken into account when treating such a patient with fever of unknown origin.

References

Günther M, Löchner-Ernst D, Kramer G, Stöhrer M . Auswirkungen des aseptischen intermittierenden katheterismus auf die männliche harnröhre. Urologe B 2001; 41: 359–361.

Campbell JB, Moore KN, Voaklander DC, Mix LW . Complications associated with clean intermittent catheterization in children with spina bifida. J Urol 2004; 171: 2420–2422.

Janicke DM, Pundt MR . Anorectal disorders. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1996; 14: 757–788.

Castaneda F, Hulbert JC, Letourneau JG, Hunter DW, Castaneda-Zuniga WR, Amplatz K . Perineal abscess after prostatic urethroplasty with balloon catheter: report of a case. Radiology 1990; 174: 49–50.

Iida S, Iuchi H, Sasaki Y, Chujyo T, Nakata Y, Saga Y et al. A case of perineal abscess due to urethral fistula in a patient with spinal cord injury (English translation of the Japanese original title). Hinyokika Kiyo 2003; 49: 567–569.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pannek, J., Göcking, K. & Bersch, U. Perineal abscess formation as a complication of intermittent self-catheterization. Spinal Cord 46, 527–529 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102142

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102142