Abstract

Objective:

Assessment of the effectiveness and safety of high daily 125 μg (5000 IU) or 250 μg (10 000IU) doses of vitamin D2 during 3 months, in rapidly obtaining adequate 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) levels.

Design:

Longitudinal study.

Subjects:

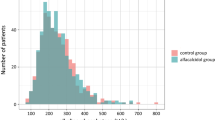

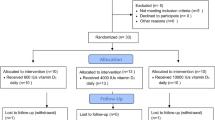

Postmenopausal osteopenic/osteoporotic women (n=38) were studied during winter and spring. Median age (25–75th percentile) was 61.5 (57.00–66.25) years, and mean bone mineral density (BMD) was 0.902 (0.800–1.042)g/cm2. Subjects were randomly divided into three groups: control group (n=13): no vitamin D2, 125 μg/day (n=13) and 250 μg/day (n=12) of vitamin D2 groups, all receiving 500 mg calcium/day. Serum calcium, phosphate, bone alkaline phosphatase (BAP), C-telopeptide (CTX), 25OHD, mid-molecule parathyroid hormone (mmPTH), daily urinary calcium and creatinine excretion were determined at baseline and monthly.

Results:

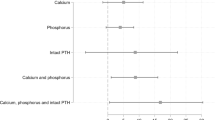

For all subjects (n=38), the median baseline 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) level was 36.25 (27.5–48.12) nmol/l. After 3 months, 8% of the patients in the control group, 50% in the 125 μg/day group and 75% in the 250 μg/day group had 25OHD values above 85 nmol/l (34 ng/ml). Considering both vitamin D2 groups together, mmPTH and BAP levels diminished significantly after 3 months (P<0.02), unlike those of CTX. Serum calcium remained within normal range during the follow-up.

Conclusions:

The oral dose of vitamin D2 required to rapidly achieve adequate levels of 25OHD is seemingly much higher than the usual recommended vitamin D3 dose (20 μg/day). During 3 months, 250 μg/day of vitamin D2 most effectively raised 25OHD levels to 85 nmol/l in 75% of the postmenopausal osteopenic/osteoporotic women treated.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Armas LAG, Hollis BW, Heaney RP (2004). Vitamin D 2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89, 5387–5391.

Arnaud CD, Tsao HS, Littlediket T (1971). Radioimmunoassay of human parathyroid hormone in serum. J Clin Invest 50, 21–31.

Bischoff H, Stahëlin H, Dick W, Akos R, Knecht M, Salis C et al. (2003). Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 18, 343–351.

Bischoff H, Willett W, Wong B, Giovannucci E, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B (2005). Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation. JAMA 293, 2257–2293.

Boff MS, Kohlmeier L, Hurwitz S, Franklin J, Wright J, Glowascki J (1999). Occult vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal women with acute hip fracture. JAMA 281, 1505–1511.

Bouillon RA, Aurweerch MD, Lissens WD, Pelemans WK (1987). Vitamin D status in the elderly, seasonal substrate deficiency causes 1,25(OH)2 cholecalciferol deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr 45, 755–763.

Brazier M, Kamel S, Maamer M, Agbomson F, Elesper I, Garabedian M et al. (1995). Markers of bone remodeling in the elderly subject: effect of vitamin D insufficiency and its correction. J Bone Miner Res 10, 1753–1761.

Chapuy MC, Arlot M, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S et al. (1992). Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med 327, 1637–1642.

Chapuy MC, Schott AM, Garnero P, Hans D, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ (1996). Healthy elderly French women living at home have secondary hyperparathyroidism and high turnover in winter. J Clin Endocrinol 81, 1129–1133.

Dawson-Hughes B, Harris S, Krall E, Dallal G (1997). Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 337, 670–676.

Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R (2005). Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporos Int 16, 713–716.

Farley JR, Hall SL, Ilacas D, Orcutt C, Miller BE, Hill CS et al. (1994). Quantification of skeletal alkaline phosphatase in osteoporotic serum by wheat germ agglutinin precipitation, heat inactivation, and a two-site immunoradiomeric assay. Clin Chem 40, 1749–1756.

Gloth FM, Gunberg CM, Hollis BW, Haddad JG, Tobin JD (1995). Vitamin D deficiency in homebound elderly persons. JAMA 274, 1683–1686.

Haden ST, Fuleihan GEH, Angell JE, Cotran NM, LeBoff MS (1999). Calcidiol and PTH levels in women attending an osteoporosis program. Calcif Tissue Int 64, 275–279.

Heaney RP, Davies KM, Chen TC, Holick MF, Barger-Lux MJ (2003a). Human Serum 25 hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr 77, 204–210.

Heaney RP, Dowell M, Hale C, Bendich A (2003b). Calcium absorption varies within the reference range for serum 25-hydroxivitamin D. J Am Coll Nutr 22, 142–146.

Koster JC, Hackeng WH, Mulder H (1996). Disminished effect of etidronate in vitamin D deficient osteopenic postmenopausal women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 51, 145–147.

Lips P, Graafimans WC, Ooms ME, Bezemer PD, Bouyrt LM (1996). The vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in elderly people: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 24, 400–406.

Malabanan A, Veronikis IE, Holick MF (1998). Redefining vitamin D insufficiency. Lancet 351, 805–806.

Mc Kenna M (1992). Differences in vitamin D status between countries in young adults and the elderly. Am J Med 93, 69–77.

Mc Kenna MJ, Freaney R (1998). Secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: means to defining hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int 8 (Suppl 2), 3–6.

Meyer H, Smedshaug G, Kvaavik E, Falch J, Tverdal A, Pedersen J (2002). Can vitamin D supplementation reduce the risk of fracture in the elderly? A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 4, 709–715.

Oliveri B, Plantalech L, Bagur A, Wittich A, Rovai G, Pusiol E et al. (2004). High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in healthy elderly people living at home in Argentina. Eur J Clin Nutr 58, 337–342.

Ooms ME, Lips P, Roos JC, Van der Vijgh WJF, Popp-Snijders C, Bezemer D et al. (1995). Vitamin D status and sex hormone binding globulin: determinants of bone turnover and bone mineral density in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 8, 1177–1184.

Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne H (2002). Vitamin D and muscle function. Osteoporos Int 13, 187–194.

Rapuri PB, Gallagher JC, Haynatzki G (2004). Effect of vitamins D2 and D3 supplement use on serum 25OHD concentration in elderly women in summer and winter. Calcif Tissue Int 74, 150–156.

Tangpricha V, Koutkia P, Rieke SM, Chen TC, Perez AA, Holick F (2003). Fortification of orange juice with vitamin D: a novel approach for enhancing vitamin D nutritional health. Am J Clin Nutr 77, 1478–1483.

Trang HM, Cole DEC, Rubin LA, Pierratos A, Shirley S, Vieth R (1998). Evidence that vitamin D3 increases serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D more efficiently than does vitamin D2 . Am J Clin Nutr 68, 854–858.

Trivedi DP, Doll R, Tee Khaw K (2003). Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomized double blind controlled trial. BMJ 326, 469–474.

Vega E, Bagur A, Mautalen C (1993). Densidad Mineral Ósea en Mujeres Osteoporóticas y Normales de Buenos Aires. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 53, 211–216.

Vieth R, Chan PCR, MacFarlane GD (2001). Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 intake exceeding the lowest observed adverse effect level. Am J Clin Nutr 73, 288–294.

Vieth R, Kinball S, Hu Amanda, Walfish PG (2004). Randomized comparison of the effects of the vitamin D3 adequate intake versus 100 mcg (4000IU) per day on biochemical responses and the well-being of patients. Nutr J 3, 8–17.

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (2000). Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 284, 3043–3045.

Yamanaka M, Ishijima M, Tokita A, Kitahara K, Enomoto F, Sawa M et al. (2004). Importance of the understanding of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D status for the alendronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Min Res 19 (Suppl 1), S463, M495.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Fundación de Osteoporosis y Enfermedades Metabólicas Óseas (FOEMO). Spedrog Caillon SAIC laboratory supplied the vitamin D2 and calcium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Guarantor: SR Mastaglia.

Contributors: SRM participated in the recruitment of subjects, the statistical analysis and the preparation of the manuscript. MSP contributed with statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript. CM and BO participated in the design of the study, the statistical analysis and the preparation of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mastaglia, S., Mautalen, C., Parisi, M. et al. Vitamin D2 dose required to rapidly increase 25OHD levels in osteoporotic women. Eur J Clin Nutr 60, 681–687 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602369

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602369

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the response of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration to vitamin D supplementation from RCTs from around the globe

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2019)

-

Vitamin D3 seems more appropriate than D2 to sustain adequate levels of 25OHD: a pharmacokinetic approach

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015)

-

Vitamin D supplementation, body weight and human serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D response: a systematic review

European Journal of Nutrition (2014)

-

Bioavailability of vitamin D2 from UV-B-irradiated button mushrooms in healthy adults deficient in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a randomized controlled trial

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2011)

-

Österreichischer Leitfaden zur medikamentösen Therapie der postmenopausalen Osteoporose – Update 2009

Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (2009)