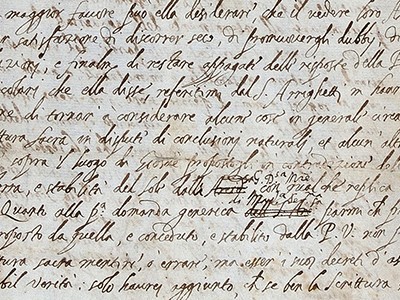

They might look old-fashioned but historical archives are crucial.Credit: AGF s.r.l./REX/Shutterstock

Modern scholars don’t always have to physically visit museums and archives around the world to seek secrets of the past. Many collections have been digitized, and much can be done with these online resources. But can anything beat the thrill of being there and finding an item assumed lost to history? That’s what happened last month at the London archives of the Royal Society, with the discovery of a letter of great historical importance.

Written by Galileo Galilei in 1613, the letter sets down for the first time the scientist’s gripes with the Vatican’s doctrine on astronomy. His forthright objections launched one of science history’s most famous battles, which culminated in the Inquisition’s condemnation of Galileo for heresy 20 years later. Different copies of the letter had circulated, and their content has been tirelessly analysed and discussed by historians. But seeing the original for the first time, with its scorings-out and word substitutions, solves a long-standing mystery about whether a version sent to the Inquisition in Rome had been doctored — and, if so, by whom.

Discovery of Galileo’s long-lost letter shows he edited his heretical ideas to fool the Inquisition

Galileo, it now seems clear, doctored his original letter himself, to make the language less aggressive, as soon as he realized the trouble heading his way. This suggests that the editing was not the malign work of theologians trying to make a stronger case against him, as had been assumed by the nineteenth-century scholar Antonio Favaro, whose 20-volume The Works of Galileo Galilei is a main reference work.

Discovering an old document that allows a gap in history to be filled is a rare event in the life of a science historian. It makes all those years spent in dusty archives — or squinting at digital archives on a screen — worthwhile. The 1613 Galileo letter could have been found by anyone, given that it was hiding in plain sight in the Royal Society’s online catalogue. So the discovery happened by chance, made by a visiting Italian scholar who was filling the last hour of his working day with an unplanned browse. Spotting a reference in the online archive, with mounting excitement, he asked to see it.

Perhaps no scientist in history has been as deeply studied as has Galileo, a prodigious scribe who is widely considered the father of the scientific method. There has been enough analysis of surviving copies of Galileo’s letters, documents and books for some scholars not to have been overly surprised that the great scientist might indeed have rewritten a little of his own history. Scholars who have pored over his works for decades, and who understand the context of his life, his personality and turns of phrase, have a feel for these things. But seeing the editing in Galileo’s own handwriting adds certainty to the interpretation. And just having the object is itself a tangible cultural gain.

There are many ways to piece history together. Research into the lives of famous people such as Galileo drives much of the knowledge we have about the past. By contrast, the Venice Time Machine (see Nature 546, 341–344; 2017), a massive project to digitize a 1,000-year archive and apply machine-learning techniques, promises to dig out knowledge about the lives of the non-famous. Offline or online, scholarly analysis or machine learning, all of these approaches combine to build a more complete perspective.

Digital resources are of inestimable value to historians, but the discovery of the Galileo letter underlines the need to protect original objects, many of them stored in vulnerable museums and libraries. So does the devastating loss of artefacts in the fire at Brazil’s National Museum in Rio de Janeiro earlier this month. We will never know if an equivalent to Galileo’s letter perished in the flames there. Some history has been lost. But some, if we can preserve it, is merely waiting to be discovered.

Discovery of Galileo’s long-lost letter shows he edited his heretical ideas to fool the Inquisition

Discovery of Galileo’s long-lost letter shows he edited his heretical ideas to fool the Inquisition

The ‘time machine’ reconstructing ancient Venice’s social networks

The ‘time machine’ reconstructing ancient Venice’s social networks

Galileo and the Pope

Galileo and the Pope