Abstract

A magnetic vortex structure stabilized in a micron or nano-sized ferromagnetic disk has a strong potential as a unit cell for spin-based nano-electronic devices because of negligible magnetostatic interaction and superior thermal stability. Moreover, various intriguing fundamental physics such as bloch point reversal and symmetry breaking can be induced in the dynamical behaviors in the magnetic vortex. The static and dynamic properties of the magnetic vortex can be tuned by the disk dimension and/or the separation distance between the disks. However, to realize these modifications, the preparations of other devices with different sample geometries are required. Here, we experimentally demonstrate that, in a regular-triangle Permalloy dot, the dynamic properties of a magnetic vortex are greatly modified by the application of the in-plane magnetic field. The obtained wide range tunability based on the asymmetric position dependence of the core potential provides attractive performances in the microwave spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dynamic properties of the magnetizations in the ferromagnetic thin films have various potential applications because of their fast time scales ranging from sub-picoseconds to nanoseconds1,2,3. The time scales of the spin dynamics are mainly determined by the saturation magnetization and the effective magnetic field due to the magnetic anisotropy. Particularly, in patterned ferromagnetic nanostructures, the intriguing magnetization dynamics can be obtained because of the significant modification of the spin excitation state compared to the uniform excitation case4. As the representative structures, a considerable attention has been focused on a magnetic vortex stabilized in a micron or submicron dot because of its unique dynamic properties with size tunability5,6,7. The domain structure of the magnetic vortex can be characterized by in-plane curling magnetization and a nanometer-sized perpendicularly magnetized vortex core. The restoring force due to the demagnetizing field and the gyrotropic force result in a spiral motion of the vortex core8.

The resonant frequency of the vortex core is in the sub GHz to GHz and can be excited by using a microwave magnetic field9,10,11,12. The oscillation frequency of the vortex core is well characterized by the effective magnetic susceptibility, which is roughly proportional to the dot aspect ratio t/D13. Here, t and D are the thickness and the diameter for the circular disk case, respectively. In the circular disk, the effective magnetic susceptibility is approximately independent of the core position because the position dependence of the core potential can be approximately described by a two-dimensional parabolic equation14,15,16. As a result, a weak field dependence of the resonant frequency is expected in a circular disk.

In the case of the elliptical disk instead of the circular disk, the resonant frequency is known to be tuned by the application of the magnetic field along the short axis for the ellipse because of the variation of the effective stiffness constant with changing the core position17. Twofold enhancement of the oscillation frequency was demonstrated by the ellipse with the aspect ratio of 2, which is defined by the ratio the major axis to the minor axis. To obtain the further increase of the frequency, the aspect ratio of the ellipse should be increased. However, the single vortex domain structure becomes unstable in the ellipse with a large aspect ratio. The modulation of the resonant frequency of the vortex core is found to depend on the core position also in the circular disk, when the pinning potential is larger than the excitation power. However, it seems to be difficult to tune the resonant frequency because the pinning potential is randomly distributed18.

To realize the large modification of the oscillation frequency with a reliable controllability, we focus on the regular triangle, in which the magnetic vortex structure is also stabilized19,20,21,22. In the triangular ferromagnetic dot, a significant increase of the core potential is expected when the core approaches the vertex of the triangle. Since the vortex chirality in a triangular micro magnet is precisely controlled by the application of the initializing in-plane magnetic field21, the core position is well manipulated by applying the magnetic field. In fact, Vogel et al. systematically studied the field dependence of the resonant frequency in the triangular vortex for the first time and demonstrated that the resonant frequency varies with the amplitude and the direction of the external magnetic field23. However, the overall change of the resonant frequency is 20 MHz, which is smaller than 10% of the resonant frequency at the original position. In the present paper, we show that, in a well-optimized device dimension and configuration, the resonant frequency in a regular triangle micro magnet varies greatly with the position of the vortex core. A wide range tuning of the resonant frequency from 200 MHz to 600 MHz is experimentally demonstrated.

Results

Mircomagnetic simulation of vortex dynamics

First, we clarify the relationship between the core position and the applied magnetic field in a triangular Permalloy (Py) dot by using an originally developed micromagnetic simulation24. Here, we focus on a regular triangle Py dot with the 2 μm in diameter of the circumscribed circle and 40 nm in thickness. In order to reflect the realistic shape of the experimentally produced triangular dot with the rounded corners, the triangle is cut by the circle with 97.5% diameter of the circumscribed circle of the triangle. The exchange constant and the saturation magnetization are, respectively, 1.0 × 10−11 J/m and 1 T, which are typical values for Py film. The computational cell size and the damping parameter α are 4 × 4 × 40 nm3 and 0.01, respectively25. We confirmed that a single vortex is stabilized at the remanent state and the chirality of the vortex can be manipulated by the application of the in-plane magnetic field, similarly to our previous study. Here, the vortex chirality was set to counter clockwise (CCW). The in-plane static magnetic field is applied along the x direction in order to move the vortex towards the vertex of the triangle. This means that the positive (negative) magnetic field induces the positive (negative) shift of the vortex core along the y direction. For a comparison, the micromagnetic configurations for a circular dot with 2 μm in diameter and 40 nm in thickness is also simulated.

Figures 1(a) and 1(b) show the relative position of the core center as a function of the in-plane magnetic field for the circular and triangular dots, respectively. The representative magnetic domain structures together with the schematics for the expected magneto-static potential under the several magnetic fields are also shown in the figures. For the circular dot, the linear field dependence is obtained, but it is limited only in the low magnetic field (|H| < 100 Oe). At the high magnetic field (|H| > 100 Oe), the dependence becomes nonlinear. The symmetric field dependence with respect to the polarity of the magnetic field originates from the perfect circular shape. On the other hand, for the triangular dot, the field dependence of the position shift is almost linear in the wide field range from −300 Oe to 400 Oe although the slope of the position shift is slightly different between the positive and negative magnetic fields. Since the strong modification of the magnetic susceptibility is expected in the triangular Py dot by changing the core position, the obtained result implies that the core oscillation frequency is widely tuned by the application of the in-plane magnetic field. We also find that, for the triangular dot with 3 μm or larger in diameter of the circumscribed circle, the moving direction of the vortex core deviates from the line perpendicular to the magnetic field because of the weak confined potential. As a result, the core position cannot be manipulated by the simple in-plane magnetic field.

Numerically calculated equilibrium core positions as a function of the in-plane magnetic field for (a) circular and (b) triangular Permalloy dots. The schematics of the expected magneto-static potential as a function of the core position together with the micromagnetic structure under each magnetic field are also shown in the right-hand side.

We then numerically study the position dependence of the vortex-resonance characteristic. The dynamic properties of the magnetic vortex have been investigated by simulating the temporal evolution of the micromagnetic structure under the small ac magnetic field with the magnitude of 2 Oe along the x axis. The steady-state vortex oscillation is reproduced by the application of a small ac magnetic field. We systematically study the amplitude of the vortex oscillation with changing the frequency of the ac magnetic field in order to find out the resonant frequency of the vortex core numerically.

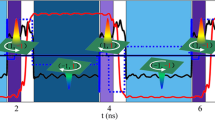

Figures 2(a) and 2(b) show the frequency dependences of the oscillation amplitudes for the circular and triangular dots, respectively, in the absence of the in-plane magnetic field. In the right-hand side of the figures, the trajectories of the vortex core under the RF magnetic field with several frequencies are plotted. Numerical simulations succeeded in capturing the resonant characteristics in both the circular and triangular dots and found that the resonant frequencies for the circular and triangular dots are 170 MHz and 220 MHz, respectively. It should be noted that the core motion makes a circular trajectory also in the triangular dot. The resonant frequency of 170 MHz for the circular dot can also be analytically reproduced by the Thiele's equation for the vortex core motion14,15. The resonant frequency for the triangular dot is larger than that for the circular one. This is because the vortex core is confined in stronger potential originating from the effectively larger surface magnetic charge in the triangular dot26. By performing the similar calculation under various dc magnetic field along the x direction, we can also evaluate the field dependence of the resonant frequency.

Numerically calculated oscillations amplitude of the vortex core confined in (a) circular and (b) triangular Permalloy dots under the constant ac magnetic field as a function of the ac frequency at the remanent state. The numerically calculated trajectory of the vortex core at each state are also shown in the right-hand side.

Figures 3(b) and 3(d) show the field dependences of the resonant frequencies for the circular and triangular dots, respectively. For the circular disk, the resonant frequency is almost constant in the field range from −250 Oe to +250 Oe. This indicates that the potential profile for the vortex core in a circular disk is well expressed by a two dimensional harmonic oscillator14,15,16. On the other hand, for the triangular dot, the resonant frequency asymmetrically changes with respect to the polarity of the magnetic field. Especially, the resonant frequency exceeds 550 MHz when the core is shifted to the corner of the triangle by applying the in-plane magnetic field of +300 Oe.

Numerically calculated resonant frequency of the magnetic vortex confined in (b) the circular and (d) triangular magnetic dots as a function of the in-plane magnetic field. The field dependences of the oscillation amplitude of the vortex core for (a) the circular and (c) triangular dots are also shown in the top.

The field dependence of the oscillation amplitude of the core at the resonance is also plotted together on the same figures (Figs. 3(a) and 3(c)). The oscillation amplitude gradually varies with changing the magnitude of the in-plane magnetic field (the core position). For the circular disk, the amplitude monotonically decreases with increasing the magnitude of the magnetic field. On the other hand, for the triangular disk, the oscillation amplitude takes a maximum value when the core is located at the center of the circumscribed circle of the triangle. At the corner, the amplitude of the core oscillation shows a significant reduction. These unique characteristics can be explained by the fact that the equivalent parabolic potential in the triangular dot changes with the core position. Thus, the resonant characteristic of the vortex confined in the regular triangle is greatly modified by applying the in-plane magnetic field along the side of the triangle.

Experimental demonstration of wide-range modulation of vortex resonance

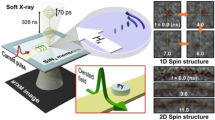

To demonstrate the expected attractive resonant properties in the triangular dot experimentally, we have measured the 1-port transmission impedance measurements (S11) of the micro strip line with the triangular dots. Here, the size of the triangular Py dot is the same as that in the simulation (2 μm in outer diameter and 40 nm in thickness). As shown in the inset of Figs. 4(a), a magnetic vortex confined in the triangular Py dot was clearly confirmed by the magnetic force microscope (MFM). For a comparison, the chain consisting of 1000 circular Py dots with 2-μm diameter and 40-nm thickness is also evaluated experimentally.

(a) Schematic illustration of 1-port transmission impedance measurement of a chain of the triangular Py dot together with MFM images for the circular and triangular Py dots at the remanent state. Experimentally obtained S11 spectra in the absence of the magnetic field for (b) the circular and (c) triangular magnetic dots.

Figures 4(b) and 4(c) show S11 spectra for the circular and triangular dots, respectively, in the absence of the dc magnetic field. In each spectrum, a clear single dip due to the vortex resonance was observed. The obtained resonant frequencies for the circular and triangular dots are, respectively, 180 MHz and 230 MHz, which are highly consistent with the numerical simulations described above.

We then study the field dependence of the resonant frequency by performing the similar measurements under the various in-plane magnetic field along the x axis. As shown in Fig. 5(a), for the circular dot, a weak field dependence of the resonant frequency, which is expected in the numerical simulation, is confirmed in the field range from −240 Oe to +240 Oe. Moreover, the wide range modulation of the resonant frequency is also reproduced in the S11 measurements for the triangular microdots, as shown in Fig. 5(b). Especially, the high frequency resonance over 500 MHz is clearly observed in the spectrum at H = 300 Oe although the magnitude of the dip is one order smaller than that for Fig. 4(c). The magnitude of the dip takes a maximum value at H ~ 100 Oe and its field dependence is fully in agreement with the numerical results.

Discussion

Although the vortex dynamics in the triangular dot has been studied in the previous experiment23, the wide range modulation of the resonant frequency from 200 MHz to 600 MHz has never been reported. The present successful experiments have been achieved by optimizing the device geometry and dimension. We use a 500-nm-wide narrow and 200-nm-thick strip line, in order to sensitively detect the vortex oscillation especially at the corner of the triangle. This is because the inductive coupling between the vortex and strip line increases with increasing the ratio of the oscillation amplitude to the width of the strip line. We also emphasize that the relative direction between the triangle and strip line rotates 90 degree from the direction in Ref. 23. This is another important fact for detecting the vortex resonance at the corner of the triangle. This improved microstrip line enabled us to study the field dependence of the vortex resonance in a circular dot more sensitively. The resonant frequency of the vortex confined in the circular disk is found to show weak field dependence, meaning that the vortex potential in a circular dot can be described by a quasi-two-dimensional parabolic potential.

In summary, we have investigated the resonant properties of the magnetic vortex confined in the triangular and circular dots. A weak field dependence of the resonant frequency, which is consistent with a quasi-two-dimensional harmonic oscillator, was observed in the circular dot. On the other hand, the resonant properties for the magnetic vortex confined in the triangular dot showed a strong field dependence because the core potential is effectively modified by the core position. Especially, the resonant frequency is found to increase significantly when the core approaches to the vertex. We may realize the wider frequency tuning range by increasing the film thickness in the triangle. Thus, a variety of the field dependence of the resonant frequency can be realized by choosing the shape and dimensions for the patterned ferromagnetic dots.

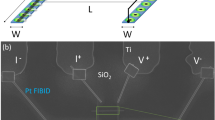

Methods

We have prepared a one-dimensional chain consisting of 1000 triangular Py dots by using the conventional lift-off technique with electron beam lithography. Here, the outer diameter and the thickness of the Py dot are 2 μm and 40 nm, respectively. A single Cu strip line, 500 nm in width and 200 nm in thickness, has been fabricated also by the electron-beam lithography and was placed on the center of the Permalloy dots for detecting the dynamic response of the magnetic vortices. The dynamic properties of the magnetic vortex have been evaluated by performing the 1-port transmission impedance measurements (S11) using the Vector Network Analyzer, as schematically shown in Fig. 4(a)27. The position of the vortex core was controlled by adjusting the external magnetic field. The vortex chirality in the triangle dots was set to CCW by using an initializing in-plane magnetic field.

References

Stohr, J. & Siegmann, H. C. Ultrafast Magnetization Dynamics, Magnetism: From Fundamentals to Nanoscale Dynamics 679–762 (Springer, 2006).

Gerrits, T., Van Den Berg, H. a. M., Hohlfeld, J., Bär, L. & Rasing, T. Ultrafast precessional magnetization reversal by picosecond magnetic field pulse shaping. Nature 418, 509–12 (2002).

Hiebert, W., Stankiewicz, a. & Freeman, M. Direct Observation of Magnetic Relaxation in a Small Permalloy Disk by Time-Resolved Scanning Kerr Microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 1134–1137 (1997).

Hillebrands, B. & Ounadjela, K. An Introduction to Micromagnetics in the Dynamic Regime, Spin Dynamics in Confined Magnetic Structures 1–34 (Springer, 2002).

Cowburn, R. P., Koltsov, D. K., Adeyeye, a. O. & Welland, M. E. Single-Domain Circular Nanomagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1042–1045 (1999).

Shinjo, T., Okuno, T., Hassdorf, R., Shigeto, K. & Ono, T. Magnetic Vortex Core Observation in Circular Dots of Permalloy. Science 289, 930–932 (2000).

Guslienko, K., Novosad, V., Otani, Y., Shima, H. & Fukamichi, K. Magnetization reversal due to vortex nucleation, displacement and annihilation in submicron ferromagnetic dot arrays. Phys. Rev. B 65, 024414 (2001).

Acremann, Y. et al. Imaging Precessional Motion of the Magnetization Vector. Science 290, 492–495 (2000).

Usov, N. a. & Kurkina, L. G. Magnetodynamics of vortex in thin cylindrical platelet. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 242–245, 1005–1008 (2002).

Ivanov, B. & Zaspel, C. High Frequency Modes in Vortex-State Nanomagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 027205 (2005).

Shibata, J., Nakatani, Y., Tatara, G., Kohno, H. & Otani, Y. Current-induced magnetic vortex motion by spin-transfer torque. Phys. Rev. B 73, 1–4 (2006).

Shibata, J. & Otani, Y. Magnetic vortex dynamics in a two-dimensional square lattice of ferromagnetic nanodisks. Phys. Rev. B 70, 2–5 (2004).

Guslienko, K., Novosad, V., Otani, Y., Shima, H. & Fukamichi, K. Magnetization reversal due to vortex nucleation, displacement and annihilation in submicron ferromagnetic dot arrays. Phys. Rev. B 65, 024414 (2001).

Thiele, A. A. Steady-state motion of magnetic domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 30, 3–6 (1973).

Guslienko, K. Y. et al. Eigenfrequencies of vortex state excitations in magnetic submicron-size disks. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 8037 (2002).

Krüger, B. et al. Harmonic oscillator model for current- and field-driven magnetic vortices. Phys. Rev. B 76, 224426 (2007).

Buchanan, K. et al. Magnetic-field tunability of the vortex translational mode in micron-sized permalloy ellipses: Experiment and micromagnetic modeling. Phys. Rev. B 74, 064404 (2006).

Compton, R. L., Chen, T. Y. & Crowell, P. a. Magnetic vortex dynamics in the presence of pinning. Phys. Rev. B 81, 144412 (2010).

Langner, H. H. et al. Vortex dynamics in nonparabolic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 85, 174436 (2012).

Cambel, V. & Karapetrov, G. Control of vortex chirality and polarity in magnetic nanodots with broken rotational symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 84, 014424 (2011).

Yakata, S., Miyata, M., Nonoguchi, S., Wada, H. & Kimura, T. Control of vortex chirality in regular polygonal nanomagnets using in-plane magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 222503 (2010).

Yakata, S. et al. Chirality control of magnetic vortex in a square Py dot using current-induced Oersted field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 242507 (2011).

Vogel, A. et al. Vortex dynamics in triangular-shaped confining potentials. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 063916 (2012).

Tanaka, T. et al. Microwave-assisted magnetic recording simulation on exchange-coupled composite medium. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 07B711 (2012).

Zhu, J.-G. & Bertram, H. N. Micromagnetic studies of thin metallic films (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 63, 3248 (1988).

Miyata, M., Nonoguchi, S., Yakata, S., Wada, H. & Kimura, T. Static and Dynamical Properties of a Magnetic Vortex in a Regular Polygonal Nanomagnet. IEEE Trans. Magn. 47, 2505–2507 (2011).

Novosad, V. et al. Magnetic vortex resonance in patterned ferromagnetic dots. Phys. Rev. B 72, 1–5 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank M. Miyata for the experimental assistance. This work is partially supported by Kurata-foundation, SCOPE and CREST.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. & K.K. carried out the experimental work, including the preparation of the sample. T.T. carried out the micromagnetic simulation including the development of simulation codes. T.K. and K.M. supervised the experimental research and micromagnetic simulation. T.K. wrote the main manuscript text and S.Y. & T.T. prepared all figures.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yakata, S., Tanaka, T., Kiseki, K. et al. Wide range tuning of resonant frequency for a vortex core in a regular triangle magnet. Sci Rep 3, 3567 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03567

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03567

This article is cited by

-

Tuning of oscillation modes by controlling dimensionality of spin structures

NPG Asia Materials (2022)

-

Spin Vortex Resonance in Non-planar Ferromagnetic Dots

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Sensitive detection of vortex-core resonance using amplitude-modulated magnetic field

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.