« Prev Next »

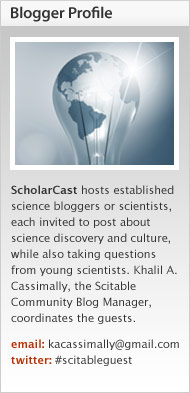

One of the stranger aspects of this lede, though, was that it was for a story about politics. American burying beetles live in significant numbers right in the path of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, and environmental groups and TransCanada, the company building the pipeline, had been fighting over the proper timing of moving them. There was science involved-the inconvenient timing of the beetles' lifecycle was what had opened up the political sparring ground, and one of the most important interviews I did was with the biology professor who oversaw the work of moving them. But since it was a political story, most of the people I was talking to were interested in the American burying beetle less as a topic of scientific inquiry and more as a means to an end.

One of the first things you learn about science is that objectivity is paramount. In politics, the opposite is true. In environmental reporting, the two often collide, and political forces try to enlist the power of science's objectivity to prove that their particular viewpoint or goal is the correct one. Follow the political fight over natural gas drilling, for instance, and you'll find both drilling proponents and opponents citing scientific papers that support their position.

To a certain extent, these are legitimate disagreements: scientists don't always agree, and new evidence can call into question the prevailing theory. But in the most extreme version of this, one side will cling to the few studies that support their position, even when that work is well outside the prevailing scientific consensus. The example that comes up most often right now is the political argument over climate science, but it's not an exclusively right-wing trait: Keith Kloor, for instance, has been making the case for a while now that left-leaning environmentalists are just as guilty of cherry-picking science about the dangers of genetically-modified crops to shore up their dislike for the GMO industry.

As a reporter covering a political story where science plays a role, this can mean that it's that much more important to check where the science is coming from-who's funding it and what the background of the researchers is. But it can also mean that there are people out there who are familiar with the issue that you're writing about and are more committed to giving you accurate information about the science than political sources might be.

In the case of Keystone XL and the beetles, the political and legal logic of this particular fight led this giant company to hire a biology professor and a team of grad students to motor around Nebraska, setting traps for the beetles, an activity which involved burying large buckets in the ground and baiting them with dead rats. When I first heard about this issue, I knew that the story would work best if I could talk to that biology professor. TransCanada wasn't likely to have much to say about this unsavory project, but I wanted to talk to someone other than the environmental groups, who were interested in the beetles' fate but also in the larger political project of blocking the pipeline's construction. Although the professor was working for the company, he was also a scientist and probably cared more about the beetles than the environmental groups that had gone to court to defend them.

He turned out to be a great person to talk to, precisely because he was a scientist. He gave me great details about burying beetles and methods of trapping them. But he also ended up speaking candidly about the potential negative impact on the beetles (which the environmental groups wanted to play up and the company wanted to play down) and about the legal gray area that had let him capture them to begin with. It's not always that easy. But in this case, the combination of science and politics made the job I had to do that much more fun.

--

Image credits: American burying beetle: USFWS Mountain Prairie (from flickr); Pipeline: Trey Ratcliff (from flickr).