Abstract

Study design:

Systematic review.

Objectives:

The objective of this study is to systematically review the literature for pediatric cases of spinal cord injuries without radiologic abnormality (SCIWORA) to investigate any possible relationship between initial neurologic impairment and eventual neurologic status.

Setting:

A university department of orthopedics.

Methods:

Following the preferred reporting items for systemic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic review, the databases of PubMed and OvidSP were electronically searched for articles that use individuals under 18 years old, have trauma resulting in spinal cord injury and have no fractures or dislocations on radiographs. When available, the patients’ age, sex, mechanism of injury and spinal cord level were recorded. Individuals with cervical injury, who had specific information on cervical level and mechanism of injury, were recorded as well. Patients who reported specific magnetic resonance imaging findings and the time from the injury were also reported. When possible, the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) was determined initially after the injury and then at last follow-up.

Results:

A total of 433 pediatric patients were identified with SCIWORA. The most prevalent mechanism of injury was sports-related injury cases (39.83%) followed by fall (24.18%) and motor vehicle-related (23.18%) injuries. The mean improvement recorded for all patients was 0.89 AIS grades.

Conclusion:

The most common mechanism of injury was sports-related and cervical injury, which occurred more frequently than other levels. Initial AIS grade A showed poorer outcomes in the pediatric population compared with the adult population. Initial presentation of D showed the highest likelihood of no permanent neurologic impairment (AIS of E).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injuries without radiologic abnormality (SCIWORA) was first described by Pang and Wilberger in 1982.1 Although now known to also occur in adults, they defined it as ‘children with objective signs of myelopathy as a result of trauma, whose plain films of the spine, tomography, and occasionally myelography carried out at the time of admission showed no evidence of skeletal injury or subluxation.’1 Mechanisms of injury for pediatric SCIWORA usually is a form of blunt trauma, including motor vehicle related, falling, sports related and child abuse.2

Swift diagnosis of SCIWORA is essential for properly managing these patients. It is possible that diagnoses could be delayed, because the negative radiographic findings make diagnosis inherently challenging. More recently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used increasingly to determine the extent of soft tissue injury.3 Treating SCIWORA usually consists of conservative management including spinal immobilization and steroid therapy.2

Since Pang and Wilberger first defined SCIWORA, there have been many case reports and case series in the literature describing this syndrome. There is one systematic review by Launay et al.,4 which was published in 2005, but there have been no recent investigations on this topic. The purpose of this study was to update the epidemiology and outcomes of the literature concerning this injury. A systematic review is necessary to distill all of the most current literature for the treatment for SCIRWORA. Such a review will provide a ‘birds-eye’ view of the larger clinical picture regarding the outcomes of SCIWORA injuries. Furthermore, another goal of this research was to see what, if any, relationship exists between the initial neurologic impairment and eventual neurologic status through mean America Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) improvement stratified by injury grade. Knowledge of such information could be of great importance for clinicians treating these injuries, as it could potentially help to achieve better outcomes in children with these conditions.

Materials and methods

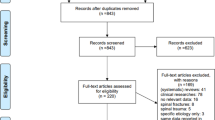

The preferred reporting items for systemic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic review were followed. On 18–19 March 2014, a systematic computerized search was performed with PubMed and OvidSP databases via four reviewers that used the same criteria and a shared Excel spreadsheet. Each reviewer was responsible for inputting certain information into the spreadsheet. This information was then corroborated by the other reviewers as they read through the information and included their own portion of the data into the spreadsheet. Therefore, this allowed for direct comparison of the same data between multiple reviewers. When discrepancies arose, they were directly addressed by the reviewers as a group. Inclusion criterias were as follows: (1) use individuals under 18 years old; (2) have trauma resulting in spinal cord injury; and (3) have no fractures or dislocations on radiographs. The entire research process is outlined in a flowchart format as Figure 1. The initial search returned 254 results—all of which were retrospective in nature. Both case reports and case series were included. Restricting the search to papers written in English language left 226 articles. Articles that were not available in full-text format via our databases or that were duplicates were removed, yielding 130 results. The OvidSP search included the following: Biological Abstracts Archive (1926–1968), Biological Abstracts Archive (1926–1968), BIOSIS Previews Archive (1926–1968), BIOSIS Previews (1969–2004), CAB Abstracts (1973–1989), CAB Abstracts Archive (1910–1972), Journals@Ovid, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid OLDMEDLINE (1946 to present), PsycARTICLES Full Text, PsycCRITIQUES (1956 to February 2014), PSYNDEXplus Literature and Audiovisual Media (1977 to February 2014), PSYNDEXplus Tests (1945 to February 2014) and Your Journals@Ovid. The search for PubMed and OvidSP was ‘((Sciwora OR Sciworet OR Sciwoctet OR spinal cord injury without abnormality OR spinal concussion)) AND (pediatric OR children OR child)’. Results were entered into a reference manager (Endnote X7, Thompson Reuters, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

The abstracts of the initial 130 articles were read, and articles that were reviews, basic science, editorials, letters to the editor, used national databases or otherwise not meeting the inclusion criteria for the study were removed, resulting in 51 papers. The full text of these papers were then more thoroughly investigated for meeting inclusion criteria. Several articles collected data from the same patient pool during the same time frame. To avoid duplicate data, this study used only articles that studied the widest time span and were the most comprehensive from that center, with the other repeated article being removed. This resulted in 31 final articles. These 31 papers were further classified by whether an AIS for each patient could be determined. AIS could be determined for 22 articles. For all 31 articles, number of patients, sex, average age, mechanism of injury, affected vertebral level, MRI findings, treatment, initial AIS, eventual AIS and mean follow-up times were all attempted to be collected. Then, using the reported initial and follow-up AIS scores, the mean improvement (or deterioration) was recorded as a positive or negative integer. Positive integers were used to reflect improvement (that is, moving from an America Spinal Injury Association score of B to A) and negative integers were used for declining America Spinal Injury Association scores. In addition, individuals with specific cervical injury, mechanism of injury and age were collected if all three were available. Lastly, patients who reported specific MRI findings and the time from the injury were also reported. Studies were also documented if the aforementioned information was not available. Descriptive analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel for Mac version 2011 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

Characteristics of children with SCIWORA

There were a total of 31 journal articles that qualified for inclusion for this study.3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 From these articles, a total of 433 pediatric patients were identified with SCIWORA. All 31 articles were retrospective in nature, with 4 (12.90%) studies being a multicenter study. There were 17 case reports (54.84%), 9 articles that had a subgroup from larger studies that were either observational or interventional in scope (29.03%) and 5 articles were case series (16.13%). Demographics and journal article details are shown in Table 1.

Mean age was documented in 401 cases with an average of 10.03 years. Sex was reported for 368 patients. There were 252 men (68.48%) and 116 women (31.52%). There were 364 cases describing the mechanism of injury. The most prevalent was sports-related injury with 145 (39.83%) cases. There were 88 cases caused by fall (24.18%) and 87 cases related to motor vehicles (23.18%). There were six cases of abuse (1.65%). There were 38 cases (10.44%) categorized as Other, which included 2 birth traumas. Spinal cord injury level was recorded for 406 cases. The most common level was cervical with 354 cases (87.19%). This was followed by thoracic with 39 cases (9.61%). There were seven cases (1.72%) spanning cervical and thoracic levels, and six patients (1.48%) with lumbar injury.

There were 62 cervical injury cases that had specific information on cervical level and mechanism of injury. The most prevalent spinal cord level involvement was C4 with 18 patients (29.03%). C7 had 16 patients (25.81%). C5 had 15 patients (24.19%), followed by C2 with 13 patients (20.97%). C3 and C6 had 12 patients each (19.35%). C8 had eight patients (12.90%). The least prevalent cervical level involved was C1 with four patients (6.45%). Figure 2 shows the involvement of cervical spinal cord levels. The most common mechanism of injury for these cases was motor vehicle related with 27 (43.55%), followed by falls with 17 (27.42%) and sports-related injury with 11 (17.74%). The least common were abuse with three (4.84%), and two each for birth and miscellaneous (3.24%). The average age of the 62 patients was 7.60 years old. Table 2 shows their demographics.

MRI findings

MRI imaging was documented as being performed in 224 patients (51.73%). Of these reports, 120 were normal (53.57%). Time from injury to initial MRI imaging was reported in 26 cases (11.61%). For these cases, the average time was 5.35 days (range: 3 h-6 weeks). The median time to initial MRI was 2 days. The mode was also 2 days. There were 42 cases that reported specific initial MRI findings (see Table 3). Edema was reported in five cases (11.90%). There was one case (2.38%) of evidence of probable stretching. Epidural hemorrhage was reported in one case (2.38%). Central disk herniation occurred one time (2.38%). T1 spinal cord hypointensity was reported seven times (16.67%). T2 hyperintensity was reported 18 times (42.86%). Epidural hematoma was reported two times (4.76%). Subdural hematoma was reported one time (2.38%). Atrophic spinal cord was reported one time (2.38%). Complete transection was reported two times (4.76%). Cerebellar ectopia was reported three times (7.14%). Changes to the conus medullaris were reported two times (4.76%). There were six cases of cord contusion (14.29%). Hematomyelia was reported five times (11.90%).

Clinical course of SCIWORA in children

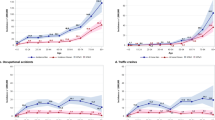

Of 31 articles, 22 contained sufficient information to apply the AIS to 263 cases. There were 183 patients (69.58%) presenting with AIS grade D, 46 patients with AIS grade A (17.49%), 20 patients with AIS grade C (7.60%) and 14 patients with AIS grade B (5.32%). There was complete recovery (AIS grade E) in 191 patients (72.62%). AIS grade D showed the highest rate of complete recovery (97.27%). This is followed by AIS grade C (35.00%) and AIS grade B (21.42%). There was no complete recovery in AIS grade A patients. Figure 3 shows initial AIS scores for each patient and the patients AIS at the time of last follow-up.

The mean improvement recorded for all patients was 0.89 AIS grades (range: −3 to 4). As shown in Figure 4, the subgroup with an initial AIS grade A improved by 0.33 grades (range: 0–3), with initial AIS grade B improved by 1.36 grades (range: 0–3), with initial AIS grade C improved by 1.20 grades (range: 0–2) and with initial AIS grade D improved by an average of 0.96 grades (range: −3 to 1). One patient’s neurologic condition deteriorated from AIS grade D to A during the observation period.7

Comparing the mean improvement of the descriptive analyses of this study’s pediatric cases to adults by Boese and Lechler37.

Management including steroid therapy, immobilization and operation was recorded on 183 occasions. Of these modalities, conservative therapy was recorded most frequently with immobilization and steroid therapy as being documented 115 times (62.84%) and 62 times (33.88%), respectively. Six cases (3.28%) were treated operatively, including one lumbar drainage and one decompression. Mean follow-up time was recorded for 65 cases with an average of 30.4 months (range: 1–66 months).

Discussion

Spinal cord injuries can be negatively life-altering injuries; thus, early diagnosis is essential to ameliorate permanent damage. In young children, spinal cord injuries may be especially challenging to diagnose early due to limited patient communication.

It is thought that children are more susceptible to SCIWORA than adults because of the relatively higher elasticity of spinal ligaments allowing for greater deformation forces on the spinal cord, without fracturing or dislocating the vertebrae. Pang2 describes anatomic features that predispose children to SCIWORA. First, a large head-to-body ratio and relatively weak neck muscles predispose the unsupported head to large flexion and extension movements. Second, the ligaments and capsules of the spine are more elastic, allowing greater force load without tearing. Third, the vertebral body endplate is fragile and breaks away from the centrum relatively easily. Fourth, the high water content of the annulus and intervertebral disk allow for longitudinal expansion. Fifth, the horizontally positioned vertebral body facet joints permit greater bony motion. Sixth, until roughly the age of 10 years, children lack uncinate processes, allowing greater rotary and lateral spinal column movement. Seventh, in young children and infants the vertebral bodies are wedged anteriorly, allowing vertebral column movement.

This study showed cervical injuries to be the most prevalent. There are several reasons for this. Young children have proportionately larger heads with more underdeveloped neck musculature. This greater head-to-body ratio leads to acceleration stress and torque to occur higher in the cervical spine, increasing susceptibility to hyperextension–extension injury.34 The articular facet joints are more horizontally oriented, which increases spine mobility and decreases stability. This arrangement may be responsible for the high incidence of cervical SCIWORA in young children.34 Ouyang et al.35 demonstrated in pediatric autopsies that the cervical spine distraction forces were significantly lower in 2- to 4-year–old children as compared with 6- to 12-year–old children. Cervical motion tends to occur much higher (C2–C3) in younger children than in adolescents or adults (C5–C6). Around 8 or 9 years of age, the fulcrum of cervical motion moves into the lower cervical spine. As children grow, the head becomes smaller and the neck musculature stronger. The articulating joints become vertically oriented and the vertebral bodies ossify, increasing stability and decreasing mobility.34

The study population for this investigation was mostly men, that is 59%. The most commonly involved spinal level was cervical with 87.19% (354 cases); thoracic was the next most common in this study 9.61% (39 cases). The lumbar spine was only involved in 1.48% (six cases) of the cases. The most common mechanism of injury in this study was sports-related injury.

The MRI findings in this study were varied, but the most common finding was T2 hyperintensity. MRI imaging is definitely sensitive for the diagnosis of a SCIWORA injury.36 However, owing to the nature of the SCIWORA injury, it could be damaging the blood supply of the nerve. One hundred and twenty (28%) of the initial MRIs were normal; this is probably because the blood supply had been slowly damaged but had yet to show up as abnormal on the MRI. However, follow-up MRIs were often not presented in the current literature for comparison. From the author’s experience, some initial MRIs may not show serious defects; however, the follow-up MRI may show a more serious abnormality. This is especially important for the watershed areas of the spinal cord. In this situation, performing a follow-up MRI imaging can demonstrate the dynamic pathological changes to the spinal cord. Visualizing these changes will allow clinicians to better provide the appropriate treatment in order to significantly improve the outcome.

Adults with SCIROWA show a different incidence of AIS grades. A recent systematic review of SCIROWA in adults by Boese and Lechler37 investigated the relative improvement by injury grade. Boese and Lechler37 showed that adults most commonly presented with AIS grade C (39.7%) and grade D (22.8%). This study shows the most common AIS grade for children was grade D (69.58%). A possible explanation for the nearly 30% higher prevalence of grade D pediatric patients is that, as children tend to be generally more predisposed to SCIRORA than adults, milder cases (grade D) arise more often. Interestingly, in adults grade A occurred at a similar rate as children (17.49% and 19.1%, respectively). Both our findings and those of Boese and Lechler37 are included in Figure 4. The mean improvement for the 567 adults was 1.07, compared with the pediatric patients in this study having a mean improvement of 0.89. The most striking difference in improvement between pediatric population and the adult population occurred in grade A, with over one complete grade improvement difference. Their adult grade A group improved 1.55 compared with this pediatric study’s grade A improvement of 0.33. The remaining grade improvements were within 0.5 of each other. The improvement of pediatric cases for grade B in this study was 1.36 compared with the adult grade B improvement of 1.55. Grade C improvement in the adult population was 0.88 compared with 1.20 in this pediatric review. Grade D mean improvement for adults was 0.62 compared with this study’s improvement of 0.96. Therefore, as is evident from the current literature, adult cases of SCIWORA have a tendency to see better improvement for the more severe grades A–B. However, it is the younger patients who see better improvement for the less severe grades C–D.

The major drawback of this systematic review is the limited specific data on SCIWORA in children. All of the accessible reports were retrospective case reports, case series and subgroups of larger case series. In addition, as this study was a review, it was not possible to determine whether other factors in the care of these patients resulted in better or worse America Spinal Injury Association scores. Therefore, as there were few prospective studies investigating the outcomes of SCIWORA in children, this topic is a fecund area for further research. A prospective study would provide a stronger level of evidence for charting the outcomes of SCIWORA injuries. Furthermore, a prospective study would also allow for a much greater level of control over the variables being investigated, thus helping to limit biases. As many articles included SCIWORA patients as a subgroup, data for these patients were frequently not as extensive. Most authors did not list AIS but instead described neurological deficits with the majority discussing motor over sensory deficits.

In conclusion, the most common mechanism of injury was sports related and cervical injury occurred more frequently than other levels. Initial AIS grade A showed poorer outcomes in the pediatric population compared with the adult population. Initial presentation of D showed highest likelihood of no permanent neurologic impairment (AIS of E).

References

Pang D, Wilberger JE Jr . Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormalities in children. J Neurosurg 1982; 57: 114–129.

Pang D . Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality in children, 2 decades later. Neurosurgery 2004; 55: 1325–1342 discussion 42-3.

Matsumura A, Meguro K, Tsurushima H, Kikuchi Y, Wada M, Nakata Y . Magnetic resonance imaging of spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormality. Surg Neurol 1990; 33: 281–283.

Launay F, Leet AI, Sponseller PD . Pediatric spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality: a meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005, 166–170.

Baker C, Kadish H, Schunk JE . Evaluation of pediatric cervical spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med 1999; 17: 230–234.

Bondurant CP, Oro JJ . Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality and Chiari malformation. J Neurosurg 1993; 79: 833–838.

Bosch PP, Vogt MT, Ward WT . Pediatric spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality (SCIWORA): the absence of occult instability and lack of indication for bracing. Spine 2002; 27: 2788–2800.

Brown RL, Brunn MA, Garcia VF . Cervical spine injuries in children: a review of 103 patients treated consecutively at a level 1 pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36: 1107–1114.

Buldini B, Amigoni A, Faggin R, Laverda AM . Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormalities. Eur J Pediatr 2006; 165: 108–111.

Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Campbell MJ . Pediatric spine fractures: a review of 137 hospital admissions. J Spinal Disord Tech 2004; 17: 477–482.

Corduk N, Koltuksuz U, Karabul M, Savran B, Bagci S, Sarioglu-Buke A . A rare presentation of crush injury: transanal small bowel evisceration. Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int 2011; 27: 1021–1024.

Dickman CA, Zabramski JM, Hadley MN, Rekate HL, Sonntag VK . Pediatric spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormalities: report of 26 cases and review of the literature. J Spinal Disord 1991; 4: 296–305.

Duprez T, De Merlier Y, Clapuyt P, Clement de Clety S, Cosnard G, Gadisseux JF . Early cord degeneration in bifocal SCIWORA: a case report. spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormalities. Pediatr Radiol 1998; 28: 186–188.

Ergun A, Oder W . Pediatric care report of spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality (SCIWORA): case report and literature review. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 249–253.

Feldman KW, Avellino AM, Sugar NF, Ellenbogen RG . Cervical spinal cord injury in abused children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008; 24: 222–227.

Florensa Vila J, Lopez-Dolado E, Arzoz Lezaun T, Gomez-Arguelles JM, Sebastian de la Cruz F, Oliviero A . A severe case of high cervical spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality. Eur Neurol 2010; 63: 188.

Grubenhoff JA, Brent A . Case report: Brown-Sequard syndrome resulting from a ski injury in a 7-year-old male. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008; 20: 341–344.

Hamilton MG, Myles ST . Pediatric spinal injury: review of 174 hospital admissions. J Neurosurg 1992; 77: 700–704.

Izma MK, Zulkharnain I, Ramli B, Muhamad AR, Harwant S . Spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality (SCIWORA). Med J Malaysia 2003; 58: 105–110.

Kim SH, Yoon SH, Cho KH, Kim SH . Spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality in an infant with delayed presentation of symptoms after a minor injury. Spine 2008; 33: E792–E794.

Lee CC, Lee SH, Yo CH, Lee WT, Chen SC . Complete recovery of spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality and traumatic brachial plexopathy in a young infant falling from a 30-feet-high window. Pediatr Neurosurg 2006; 42: 113–115.

Liao CC, Lui TN, Chen LR, Chuang CC, Huang YC . Spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality in preschool-aged children: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging findings with neurological outcomes. J Neurosurg 2005; 103 (1 Suppl): 17–23.

Mahajan P, Jaffe DM, Olsen CS, Leonard JR, Nigrovic LE, Rogers AJ et al. Spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormality in children imaged with magnetic resonance imaging. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 75: 843–847.

Mann DC, Dodds JA . Spinal injuries in 57 patients 17 years or younger. Orthopedics 1993; 16: 159–164.

Mortazavi MM, Mariwalla NR, Horn EM, Tubbs RS, Theodore N . Absence of MRI soft tissue abnormalities in severe spinal cord injury in children: case-based update. Childs Nerv Syst 2011; 27: 1369–1373.

Pollina J, Li V . Tandem spinal cord injuries without radiographic abnormalities in a young child. Pediatr Neurosurg 1999; 30: 263–266.

Robles LA . Traumatic spinal cord infarction in a child: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol 2007; 67: 529–534.

Sanchez B, Waxman K, Jones T, Conner S, Chung R, Becerra S . Cervical spine clearance in blunt trauma: evaluation of a computed tomography-based protocol. J Trauma 2005; 59: 179–183.

Shen H, Tang Y, Huang L, Yang R, Wu Y, Wang P et al. Applications of diffusion-weighted MRI in thoracic spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality. Int Orthop 2007; 31: 375–383.

Trigylidas T, Yuh SJ, Vassilyadi M, Matzinger MA, Mikrogianakis A . Spinal cord injuries without radiographic abnormality at two pediatric trauma centers in Ontario. Pediatr Neurosurg 2010; 46: 283–289.

Trumble J, Myslinski J . Lower thoracic SCIWORA in a 3-year-old child: case report. Pediatr Emerg Care 2000; 16: 91–93.

Wang MY, Hoh DJ, Leary SP, Griffith P, McComb JG . High rates of neurological improvement following severe traumatic pediatric spinal cord injury. Spine 2004; 29: 1493–1497 discussion E266.

Yamaguchi S, Hida K, Akino M, Yano S, Saito H, Iwasaki Y . A case of pediatric thoracic SCIWORA following minor trauma. Childs Nerv Syst 2002; 18: 241–243.

Platzer P, Jaindl M, Thalhammer G, Dittrich S, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Vecsei V et al. Cervical spine injuries in pediatric patients. J Trauma 2007; 62: 389–396 discussion 94-6.

Ouyang J, Zhu Q, Zhao W, Xu Y, Chen W, Zhong S . Biomechanical assessment of the pediatric cervical spine under bending and tensile loading. Spine 2005; 30: E716–E723.

Bou-Haidar P, Peduto AJ, Karunaratne N . Differential diagnosis of T2 hyperintense spinal cord lesions: part B. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2009; 53: 152–159.

Boese CK, Lechler P . Spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormalities in adults: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 75: 320–330.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carroll, T., Smith, C., Liu, X. et al. Spinal cord injuries without radiologic abnormality in children: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 53, 842–848 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.110

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.110

This article is cited by

-

Clinical characteristics analysis of pediatric spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality in China: a retrospective study

BMC Pediatrics (2024)

-

Spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormality: an updated systematic review and investigation of concurrent concussion

Bulletin of the National Research Centre (2023)

-

Real spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormality in pediatric patient with tight filum terminale following minor trauma: a case report

BMC Pediatrics (2019)

-

Management of cervical spine trauma in children

European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (2019)

-

Spondylotic traumatic central cord syndrome: a hidden discoligamentous injury?

European Spine Journal (2019)