Abstract

Objective:

To validate the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core sets for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) in the early post-acute and long-term context from the perspective of occupational therapists (OTs).

Setting:

International

Methods:

OTs experienced in the treatment in SCI were asked about problems, resources and aspects of the environment treated by them, in a three-round electronic mail survey using the Delphi technique. Responses were linked to the ICF by two researchers; kappa coefficient was calculated as statistical measure of agreement.

Results:

In total, 67 experts from 27 countries named 2586 different concepts. For the early post-acute context, 223 concepts were linked to ICF categories. Three ICF categories from the component body function, three ICF categories from the component body structures and five ICF categories from the component activities and participation were not represented in the ICF core set for the early post-acute context with an expert agreement of more than 75%. For the long-term context, 205 concepts were linked to ICF categories. Two ICF categories from the component body function, four ICF categories from the component body structures and two ICF categories from the component activities and participation were not represented in the ICF core set with an expert agreement of more than 75%.

Conclusion:

OTs addressed a vast variety of problems that they take care of in their interventions in persons with SCI. The Comprehensive ICF core sets covered a high percentage of these problems. Further research is necessary on a few aspects that are not included in the ICF core sets for SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustaining a spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating event that leads to many changes that are unanticipated, immediate and often permanent. Damage of neural elements of the spinal cord within the spinal column causes impairment or loss of motor and sensory function. This damage is associated to a large range of limitations in activities and restrictions in participation.1

Occupational therapy is characterized by first focusing on everyday occupations in their clients’ life in order to encourage and enable them to take advantage of their resources; second engaging them in daily occupations and participation, and focusing on the individual with respect to those daily occupations that are meaningful to them individually, given their environment and stage of life. From this background, occupational therapists (OTs) provide services that facilitate health and well-being, enhance function, independence and productivity in the context of people's environment and across their lifespan. OTs work in a variety of institutional, community-based and organizational settings.2 As an essential group of professionals, OTs are involved in the treatment of persons with SCI in different healthcare settings. They work as single professionals and within multidisciplinary teams, in which it is important that everyone shares a common understanding of functioning and disability.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)3 provides this common understanding and common descriptive language. The ICF offers a comprehensive and universally accepted framework for describing functioning, disability and health in persons with all kinds of health conditions including SCI.3 According to the ICF, the problems associated with a disease or injury include those involving body functions and body structures as well as problems in activities and participation. These problems are the result of an interaction between the direct consequences of the disease or injury and features of the person's life situation, which in the ICF are termed contextual factors and include both environmental and personal factors. The detailed hierarchical structure of the biopsychosocial model of the ICF is presented in Figure 1.

To facilitate the implementation of the ICF into the SCI rehabilitation process, ICF core sets for individuals with SCI in the early post-acute4 and the long-term context5 have been developed. These ICF core sets are selections of ICF categories relevant to persons with SCI, 162 categories for persons in the early post-acute context and 168 categories for persons in the long-term context. The early post-acute context covers any setting in which the first comprehensive rehabilitation after the acute SCI is provided. The long-term context refers to any setting in which care is provided after ending comprehensive rehabilitation.5

The standard methodology for the development of ICF core sets includes collecting evidence from preparatory qualitative and quantitative studies, followed by a formal expert consensus process, which is then followed in turn by a validation phase. A key element of the validation process focuses on whether the problems addressed by health professionals working in a multidisciplinary team are adequately covered in a core set. In the case of SCI, OTs represent an essential professional group involved in the treatment of persons with SCI in different healthcare contexts and from whose perspective ICF core sets need to be validated.2 One specific issue of their content validity is whether the ICF core sets cover the clients’ problems that OTs find relevant and take care of their interventions.

The objective of this study is therefore to validate the ICF core sets for SCI in the early post-acute and long-term care contexts from the perspective of OTs.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted as a worldwide electronic-mail survey applying a three round Delphi technique with invited OTs. The Delphi technique enabled experts to repeatedly access the group, explore the complex issues and obtain consensus.6

Recruitment of participants

Persons with training as OTs and experience in the field of SCI were eligible to participate in this study. A worldwide database of experts in SCI was compiled by the ICF Research Branch at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, Germany within the project ‘Development of ICF core sets for Spinal Cord Injury’. This database was the basis for the recruitment in the validation of the ICF core sets in SCI. To recruit additional participants, occupational therapy associations, universities, specialized care units, hospitals and other institutions were identified by internet search and contacted. To determine expertise, author searches were undertaken and personal recommendations followed up. Experts were invited to recommend other OTs with expertise in SCI (snowball sampling). Possible participants received an information pack with study details and were asked to consent in writing, before being enrolled in the study.

Delphi process

In the first Delphi round, the experts received an open-ended questionnaire. They were asked to list problems, resources as well as aspects of the environment relevant to the treatment that OTs provide for persons with SCI, first for the early post-acute and second for the long-term context (Figure 2). Answers were tabulated and linked to the ICF7 (see below ‘Linking’). In addition, experts completed questions on demographic characteristics and professional experience. In the second Delphi round, experts decided whether to agree that the respective ICF categories represent patients’ problems, patients’ resources or aspects of their environment that were taken into account for the treatment provided for persons with SCI by OTs.

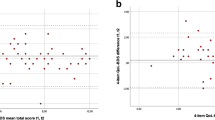

To maintain participants' motivation, only a selection of the ICF categories from the second round was included in third round. A modified Scree test was applied to identify ICF categories for which consensus was not reached.8 A graph was plotted containing the percentages of expert agreement for each ICF category. The Scree line was placed on the downward slope. Points close to the Scree line indicated an insufficient endorsement and were included into Delphi round three.

In the third Delphi round, the ratings were tabulated with frequencies of answers from the previous round to inform decisions other experts had made. Experts were requested to reconsider their answers. Within the Delphi process, questionnaires were returned within 3–5 weeks for each round.

Linking

Each response in the first Delphi round was linked to ICF categories by two researchers, according to published linking rules.7 Each ICF category was coded with a letter for the components: body functions (b), body structures (s), activities and participation, (d) environmental factors (e) and a code of one to five digits (Figure 1). Disagreements were discussed with supervisors and a joint decision was made. According to the ICF, description personal factors were coded as personal factors. Responses that could not be assigned to ICF categories were coded as not-covered.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and frequencies of ratings. Kappa coefficient was calculated with bootstrapped confidence intervals to analyze the agreement between the two researchers linking the participants’ answers to the ICF.9

ICF categories that reached an agreement of more than 75% among the participants in the final Delphi round were considered for comparison with the comprehensive ICF core set for SCI. As no universal agreement on the level of consensus exists, based on experience from previous studies10, 11 this cut-off-point was considered to be the appropriate level of consensus to be achieved.

Results

Recruitment

Ten OTs were recruited out of 254 experts in SCI from a worldwide database. An additional 47 experts were suggested by this group and agreed to participate. One hundred forty-six associations were contacted, and newsletters or e-mails were sent to their members. Out of 341 individually invited specialists, 17 agreed to participate. Twelve experts were found by author search, two agreed. Fifty-four institutions were contacted, 7 experts were recruited. Eighty-seven experts were contacted individually and two participated. From the 85 recruited experts, 82 persons out of 27 countries were eligible for inclusion and agreed to participate in the Delphi survey. Table 1 details the attrition of participants between the Delphi rounds, demographics and professional experience.

Delphi process

The Delphi survey was conducted from April- to August-2009. The first-round questionnaires were returned by 92.7% of the participants, one questionnaire was excluded because it was not completed. Four questionnaires were not returned for unknown reasons. One questionnaire was not returned due to sickness. The second-round questionnaire was returned by 88.2% of the experts. According to the Scree test, 110 categories for the early post-acute and 99 categories for the long-term context with inexplicit consensus among the second-round participants were included for the third round. The response rate for the third round was 100%. The questionnaire was provided in the subsequent rounds only to participants who responded in the previous round. Reminders were sent in case there was no reply from the participants.

Linking

In the first Delphi round, 2586 patients’ problems, resources or aspects of the environment relevant to treatment of SCI by OT's were identified for the early post-acute and long-term context. The answers were linked to 223 ICF categories for the early post-acute and 205 ICF categories for the long-term context (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5). In all, 32 answers were linked to the personal factors; 33 responses for the early post-acute and 22 answers were linked for the long-term context (Table 6). Three responses were found to be not-covered by the ICF, two responses for the early post-acute and three for the long-term context. (Table 7).

The kappa statistics with a bootstrapped confidence interval for the linking was for the early post-acute 0.46 (0.43–0.49) and for the long-term context 0.40 (0.36–0.44).

Representation of OT responses in the comprehensive ICF core sets for SCI

Participants’ responses with an agreement of more than 75% in the final round were considered for comparison with the comprehensive ICF core set for SCI.

From the component body functions, 44 categories are part of the ICF core set in the early post-acute, 38 in the long-term context (Table 2). Few responses were linked for the early post-acute context to the third-level categories for example, b7101 Mobility of several joints, and in the core set they are represented by the second-level category b710 Mobility of joint functions. For the long-term context, answers were linked to the third-level category for example, b7150 Stability of a single joint. These categories are represented as second-level category such as b715 Stability of joint functions. Three categories with an agreement of more than 75% were not included in the core set for the early post-acute context: b164 Higher level cognitive functions, b1801 Body image and b7200 Mobility of scapula, for the long-term context, two categories were not included: b1801 Body image and b755 Involuntary movement reaction functions.

From the component body structures, 11 categories for the early post-acute context are included in ICF core set. Several responses were linked to third-level categories. Structure of the lower leg (s7501) was represented in the ICF core set as s750 Structure of the lower extremity. Nine categories for the long-term context are included in the ICF core set. Few responses for the long-term context linked to third-level categories are represented in the ICF core set as second-level categories for example, s7201 Joints of the shoulder regions, was represented as s720 Structure of the shoulder region. Three categories with an agreement of more than 75% were not included in the core set for the early post-acute and four categories for the long-term context are not included in the ICF core set, such as s760 Structure of the trunk for the long-term context and for both contexts s770 Additional musculoskeletal structures related to the movement, s7701 Joints and s7702 Muscles.

From the component activities and participation, 83 categories for the early post-acute and 84 in the long-term context are included in the ICF core set (Table 4). In some cases, third-level categories such as d3600 Using telecommunications devices and d3601 Using writing machines were represented as second-level categories in the core set for the early post-acute context. In the long-term context d620 Acquisition for goods and services is represented in the core set as d6200 Shopping by the experts. Five categories with an agreement of more than 75% were not included in the core set: d155 Acquiring skills, d170 Writing, d177 Making decisions, d6504 Maintaining assistive devices and d6505 Taking care of plants, indoor and outdoor for the early post -acute context. Two categories were not included for the long-term context, d170 Writing and d177 Making decisions.

From the component environmental factors, all ICF categories with an agreement >75% are represented in the ICF core sets, namely 42 categories in the early post-acute and 45 in the long-term context (Table 5).

In all, 32 answers were linked to the not yet developed ICF component personal factors, 23 responses for the early post-acute and 22 responses for the long-term context. The majority of these issues addressed health conditions related to SCI. A few responses described coping strategies for example, realistic goal setting (Table 6). Five issues were not-covered by the core sets (Table 7).

Discussion

We found that the categories of the current versions of the ICF core sets for SCI largely agree with what OTs consider problems, resources and aspect of the environment relevant to their treatment of persons with SCI. However, some ICF categories were not included in the ICF core sets and need to be discussed.

In the component body functions, b1801 Body image was named by the participants, but not included in ICF core sets for SCI. The opinion of the participants is consistent with studies, which demonstrated that physical impairments result in a changed body, which affects physical and psychosocial well-being, and performance.12, 13

The category b164 Higher level cognitive functions was mentioned by the participants. In agreement with previous research, the ICF category b755 Involuntary movement reaction functions was considered as relevant not only for the early post-acute context, but also for the long-term context by the participants in our study.14, 15 Furthermore, the participants highlighted the relevance of b7200 Mobility of scapula, which is not included in ICF core sets for the early post-acute context.14

Categories from the component body structures that are not represented in the ICF core sets for both contexts were s770 Additional musculoskeletal structures related to movement, s7701 Joints and s7702 Muscles. This is supported by research, which shows that OTs must have sound knowledge in joint protection techniques and in ergonomic principles, as they are taking care for movement-related structures in their treatment.16, 17 Thus, it seems important to include this category in the ICF core sets to assure a comprehensive description of OT interventions.

From the ICF component activities and participation, d177 Making decisions and d175 Problem solving were mentioned by the participants, but are not represented in the ICF core sets for SCI. In fact, OTs help their clients to select and implement appropriate strategies to overcome challenges of their new situation. Effective problem-solving was found to be a key factor to master their changed life.12, 13 Furthermore, the ICF categories d155 Acquiring skills and d170 Writing clearly reflect problems of persons with SCI. For example, persons after forearm tendon transfer surgery need to acquire and learn new skills including writing and to use their ‘new hands’.18 The relevance of topics such as solving problems, making decisions and learning for the professional work in occupational therapy is supported by professional boards for example, the National Board for Certification in Occupational Therapy.19 Thus, from the perspective of OTs, an inclusion of those categories in the ICF core sets for SCI might be useful.

As assistive devices are often essential for the clients’ participation in every day life,20 the education and training on the use and maintenance of assistive devices is an important part of occupational therapy. Consequently, it could be useful to add d6504 Maintaining assistive devices to the ICF core set for the early post-acute context.

The participants also addressed category d6505 Taking care of plants indoors and outdoor, which is not considered in the ICF core set for the early post-acute context. The therapeutic relevance of the role of taking care for plants is reported in research. Problems are addressed, such as cognitive reorganization, mental healing, prevocational assessment, recreation, teaching of ergonomics, training of sensory motor function, learning to work with assistive devices and social interaction.21 However, it remains questionable why the participants highlighted this category. Further research on this finding is necessary.22, 23, 24, 25, 26

It is important to mention the interaction across the ICF components. If persons have problems in higher cognitive functions, such as abstraction, insight and judgment, concept formation and mental flexibility, the corresponding activities are also negatively influenced and the treatment process is affected. As categories d177 Making decisions and d175 Problem solving were mentioned by the OTs on the activity/participation level it seems likely that the work of OTs is on one hand focusing on facilitating the individuals ability to select and implement appropriate strategies and evaluate the results. On the other hand, to facilitate the ability to generate strategies that may be used to resolve problems. Learning ability, effective problem-solving and d155 Acquiring skills, d177 Making decisions help persons with SCI to overcome challenges of their new situation and was found to be a key factor to successfully participate in the changed life.12, 13

However, problems with cognitive functions do not only interfere with OT treatment, but also complicate the treatment process of all involved health professions. As different professions have a different focus on complex and multidimensional problems, like higher-level cognitive functions, the unifying language and framework of the ICF core sets could improve client-orientation and efficiency in the rehabilitation process considering the diverse perspectives of the health professionals.

Personal factors are not yet classified in the ICF. In our survey, a large number of personal factors were identified mainly related to health conditions, age, coping or adapting to the new role. Thus, it could be useful to develop the ICF component personal factors to enable health professionals to comprehensively and systematically describe relevant aspects influencing a patient's functioning and health.

The responses not covered by the ICF addressed training and education of the family, personal assistants and careers of persons with SCI. Although these persons are not the targets of the ICF and consequently no categories exist to classify their functioning and health, the ICF recognizes their influence on the persons with SCI in the chapter e3 Support and relationships (Table 7).

Concerning methodological limitations and strengths, the following aspects should be considered. The Delphi technique was an appropriate method for this study objective. With a total response rate of 81.7%, the criterion of a minimum 70% response rate was clearly exceeded.6 According to the kappa coefficient there was a moderate agreement of the linking researchers.

A potential selection bias cannot be excluded. Random sampling was not possible as no database is available with sufficient number of the targeted population. The Delphi method rather uses experts in the area of interest.6 Furthermore, there are limitations in the external validity. Although experts from all world regions were participating, there was an underrepresentation of the African Region, Eastern Mediterranean Region and South East Asia Region. No experts could be recruited in South or Middle Americas. Health services might not yet be established for SCI. Language barriers might have been another reason as the Delphi survey was conducted in English language only.

Conclusion

This study supports that the comprehensive ICF core sets in SCI are relevant to the clinical practice of OTs and provide a useful basis to describe and classify functioning, health and disability with a common framework and language. The comprehensive ICF core sets covered a majority of problems treated by OTs in persons with SCI. Further research is necessary on a few aspects not included. Further results on the validity of the ICF core sets will be available from studies involving perspectives from physical therapists, physicians, psychologists, nurses and social workers.

References

Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Post M, Asano M . Participation after spinal cord injury: the evolution of conceptualization and measurement. J Neurol Phys Ther 2005; 29: 147–156.

WFOT. About Occupational Therapy http://www.wfot.org/office_files/ABOUT%20OCCUPATIONAL%20THERAPY%282%29 pdf (accessed 16 March 2010).

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. WHO: Geneva, 2001.

Kirchberger I, Cieza A, Biering-Sørensen F, Baumberger M, Charlifue S, Post MW et al. ICF core sets for individuals with spinal cord injury in the early post-acute context. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 297–304.

Cieza A, Kirchberger I, Biering-Sørensen F, Baumberger M, Charlifue S, Post MW et al. ICF core sets for individuals with spinal cord injury in the long-term context. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 305–312.

Sharkey SB, Sharples AY . An approach to consensus building using the Delphi technique: developing a learning resource in mental health. Nurse Educ Today 2001; 21: 398–408.

Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustün B, Stucki G . ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 212–218.

Zoski K, Jurs S . Priority determination in surveys. An application of the Scree-test. Eval Rev 1990; 14: 214–219.

Vierkant RA . SAS Macro for Calculating Bootstrapped Confidence Intervals about a Kappa Coefficient 2004. http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi22/STATS/PAPER295.PDF. (accessed 21.2.2010).

Kirchberger I, Cieza A, Stucki G . Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for rheumatoid arthritis: The perspective of psychologists. Psychol Health 2008; 23: 639–659.

Lemberg I, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, Cieza A . The ICF core set for stroke from the perspective of physicians: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2010; 46: 377–388.

Donaghy M, Nichol M, Davidson K (eds). Introduction. In: Cognitive Behavioural Interventions in Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy, 1st edn. Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier: Edinburgh. 2008.

Elliott TR, Godshall FJ, Herrick SM, Witty TE . Problem-solving appraisal and psychological adjustment following spinal cord injury. Cognit Ther Res 1991; 15: 387–398.

Watanabe T . The role of therapy in spasticity management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 83 (suppl): S45–S49.

Ozelie R, Sipple C, Foy T, Cantoni K, Kellogg K, Lookingbill J et al. Classification of SCI rehabilitation treatments SCI rehab project series: The occupational therapy taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med 2009; 32: 283–297.

Goldstein B . Musculoskeletal conditions after spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2000; 11: 91–108.

National Office of OT Australia (Occupational Therapy Association of Australia. Australian Competency Standards for Entry-Level Occupational Therapists, OT Australia National 1994 Fitzroy Victoria 3065 www.ausot.com.au. (accessed 21.3.2010).

Sinnott AK, Brander P, Siegert RJ, Alastair G, Rothwell AG, De Jong G . Life impacts following reconstructive hand surgery for tetraplegia. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2009; 15: 90–97.

National Board for Certification in Occupational Therapy, Inc. A practice analysis study of entry–level occupational therapists registered and certified occupational therapy assistant practice. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health 2004; 24 Supplement.

Samuelson K, Wressle E . User satisfaction with mobility assistive devices. Disabil Rehabil 2008; 30: 551–558.

Söderback I, Söderström M, Schälander E . Horticultural therapy: the ‘healing garden’ and gardening in rehabilitation measures at Danderyd Hospital Rehabilitation Clinic, Sweden. Pediatr Rehabil 2004; 7: 245–260.

Chau L, Hegedus L, Praamsma M, Smith K, Tsukada M, Yoshida K et al. Women living with a spinal cord injury: perceptions about their changed bodies. Qual Health Res 2008; 18: 209–221.

Bassett RL, Ginis KM, Buchholz AC . A pilot study examining correlates of body image among women living with SCI. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 496–498.

Kielhofner G . Model of Human Occupation—Theory and application 3rd Edition 2002. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Maryland.

Law M, Stanton S, Polatajko H, Baptiste S, Thompson- Franson T, Kramer C et al. 1997 Enabling occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. CAOT Publications: Ottawa.

Chapparo C, Ranka J (Eds) Occupational Performance Model (Australia) http://www.occupationalperformance.com/ (accessed 10 10 2010).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil, Switzerland. We like to thank the participants in the Delphi survey for their valuable contribution and their time in responding to the demanding questionnaires: Helena Aagaard, Meenakshi Batra, Vijay Batra, Aileen Bergström, Susanne Berner Nielson, Sarah Bogner, Alison Camp, Amanda Carr, Cathy Cooper, Tu Dang Van, Allie Di Marco, Elena Donoso-Brown, Brian Dudgeon, Kimberly Eberhard, Monika Edenhofer, Bettina Enders, Lydia Engelbrecht, Joaquim Faias, Valeria Finarelli, Henrica Fransen-Jaïbi, Sigrun Gardarsdottir, Mireille Goy, Hanne Gregersen, Theresa Gregorio-Torres, Karen Hammell, Cindy Hartley, Martha Horn, Iqbal Hossain, Gera Hulting, Mary Hutchison, Yuh Jang, Raimonda Kavaliauskaitë, Sabine Kerlin, Juliane Kirsch, Zdenko Koscak, Ruth Krahl, Mirijana Kucina, Lene Laier, Laleh Lajevardi, Anne Marie Langan, Rafferty Laredo, Emma Linley, Jana Löhr, Carola Lösel, Caroline Lovey, Angelika Lusser-Gantzer, Alison Mannion, Hui-Fen Mao, Cynthia Nead, Clare Nixon, Soo Oh, Shangdar Maring Ronglo, Vardi Rubin, Claudia Rudhe, Annelie Schedin Leiulfsrud, Ellen Severe, Narges Shafaroudi, Ulla Stoll, Narumon Sumin, Dorinda Taylor, Laura Valsecchi, Michelle Verdonck, Molly Verrier, Johanna Wangdell, Eric Weerts, Wachiraporn Wittayanin, Verena Zappe, Stephanie Zuk. The authors also thank Cristina Bostan from the ICF Research Branch in Munich for her contribution to calculate the kappa coefficient and Anita Henniger for her most helpful support regarding the linking process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herrmann, K., Kirchberger, I., Stucki, G. et al. The comprehensive ICF core sets for spinal cord injury from the perspective of occupational therapists: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique. Spinal Cord 49, 600–613 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.168

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.168

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Content comparison of the Spinal Cord Injury Model System Database to the ICF Generic Sets and Core Sets for spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

Challenges and potential improvements in the admission process of patients with spinal cord injury in a specialized rehabilitation clinic – an interview based qualitative study of an interdisciplinary team

BMC Health Services Research (2017)

-

Rehabilitation goals of people with spinal cord injuries can be classified against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for spinal cord injuries

Spinal Cord (2016)

-

Impact of joint contractures on functioning and social participation in older individuals – development of a standard set (JointConFunctionSet): study protocol

BMC Geriatrics (2013)