Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objectives:

To report on a case of paraganglioma presenting in an uncommon extradural thoracic localization.

Setting:

Department of Neurosurgery, Florence, Italy.

Case report:

A 43-year-old woman with a thoracic lesion extending into the extradural space along four levels, T1–T4, presented with sudden spastic incomplete paraplegia and paresthesia at the lower limbs.

Results:

The neoplasm was surgically resected ‘en bloc’ and histological findings corresponded to paraganglioma. One year after surgery, the patient was walking without assistance, a T3–T4 hypoesthesia was still present and an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study showed no signs of focal recurrence.

Conclusions:

The imaging features of thoracic paragangliomas may be misleading and an advanced malignant lesion could be primarily suspected; thus, a histological study is always needed. Total resection is the gold standard therapy. Owing to the risk of recurrence or multicentric growth, follow-up must be prolonged and accurate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Paragangliomas are tumors originating from the sympathetic or parasympathetic autonomic nervous system associated to the paraganglias, most frequently found in the jugular glomus and the carotid bodies (90% of all paragangliomas). There is no precise data in the literature about prevalence of spinal paragangliomas. Most cases describe the lesions as extramedullary and intradural, most frequently sited at the level of the cauda equina and the filum terminale.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Findings in the extradural space at a cervical or dorsal spinal level are particularly rare.1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

We describe the case of a thoracic extradural paraganglioma invading the thoracic cavity. A revision of the literature is reported.

Case report

During alopecia treatment with steroids, a 43-year-old woman suffered acute pain involving the interscapular region, the shoulder and the right arm with paresthesia and weakness in the legs and was transferred to our department. At examination, incomplete spastic paraplegia, hypoesthesia in T3 and T4 dermatomes bilaterally with a Lhermitte sign, and incomplete ptosis with a slight miosis in the right eye were found. Blood and urine chemical and physical tests were normal, as were blood pressure values.

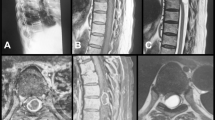

Computed tomography (CT) scans showed an almost spherical, 3.13 cm mean diameter, mediastinic mass that greatly enlarged the right vertebral foramina at the T2 and T3 level (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the lesion as hypo-iso-intense in T1 and iso-hyper-intense in T2 while contrast enhancement was intense and homogeneous. The lesion distorted the medulla and surrounded the right nerve roots at these levels (Figure 2).

CT scans with contrast enhancement showing this irregularly spherical 2.79–3.46 cm lesion in the high thoracic cavity penetrating through the vertebral foramina between the vertebrae T2 and T3 and eroding the right half of the vertebral body with the corresponding pedicle. Clear bone-tumor demarcation is observable

Although the imaging characteristics were not of clear infiltration but rather of expansion (dislocated dural theca and vertebral osteolysis with hyperdense margins), the diagnosis of a primitive lung tumor invading the vertebrae was advanced.

Abdomen and thorax contrast-CT scans and bone scintigraphy excluded the presence of other lesions.

Owing to the equivocal interpretation of the imaging study and considering the neurological conditions, despite visceral involvement, it was decided to treat the lesion surgically. In the prone position, a median incision centered on T2 and arcuately prolonged under the right scapula was performed. Thoracotomy was achieved and a voluminous extrapleuric mass, adherent to the T2–T3 vertebral bodies and to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th right ribs, was visible. The macroscopic aspect was an irregularly ovoid, variegated rosy–reddish lesion with duro-elastic consistency, which surrounded two consecutive nerve roots (right T3 and T4). After having incised the affected ribs, a right T2–T3 lamino-arthro-transversectomy was performed, and the lesion was easily detached. A partial T2 somatectomy allowed ‘en bloc’ removal of the lesion including its thoracic part. An expansible cylinder (ADD, Anterior Distraction Device, Ulrich, Germany) was introduced to replace the removed body and one longitudinal bar fixed with hooks on the C7 and T4 right laminae was inserted (Figure 3).

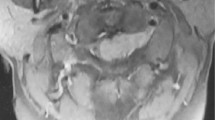

The surgical specimen was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin or mounted on electrostatic slides for immunohistochemical study. Light microscopy revealed polygonal cells with a pink-stained granular cytoplasm and rounded, occasionally pleomorphic, nuclei showing fine chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli in a prominent stromal and vascular hyalinization. Tumoral cells formed lobules and cords often obscured by the hyalinization phenomena. Mitoses were not seen. Immunohistochemically, the lesion was SP, NF, NSE, S-100 protein, and CHROMO A positive. No tumoral labeling was observed for VIM, CK, and EMA. The proliferation index, estimating the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells was low (1%) (Figure 4).

Hematoxylin–eosin-stained section: (a) (original magnification × 10) and (b) (original magnification × 20) showing polygonal cells, rarely pleomorphic, organized in lobules and cords, in a prominent vascular and stromal hyalinization and wide areas of necrosis. Immunohistochemical study ((c–f): original magnification × 20) showing, respectively, chrono A, NF, S100, SY positive

Postsurgically, the patient presented T3–T4 hypoesthesia as well as progressive resolution of the hyperreflexia and the ability to walk without assistance. A slight right Horner Syndrome persisted.

At 1 year from surgery, the area of hypoesthesia shrank and only a slight drooping of the upper eyelid persisted. No residual or recurrent lesion was detected on MRI.

Discussion

Extraadrenal (10–15%) and adrenal (85–90%) paraganglial tumors associated with the sympathetic nervous system (always chromaffine), produce catecholamine in 50% of the cases but rarely release it and thus are rarely symptomatic (weight loss, hypertension, flushing, sweating, tremors, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, etc). Parasympathetic autonomic nervous system paragangliomas are nonchromaffine and rarely produce catecholamine.4, 16

Spinal paragangliomas are rare and there is no agreement on their origin since there are no paraganglias in this region (sympathetic autonomous medullar nerves or heterotopic cells).6 Their most common localization is intradural extramedullar in the lumbosacral tract. We found only eight cases of thoracic primitive nonsecernent extradural paragangliomas in the literature and only two cases of thoracic extradural secernent ones1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15 (Table 1). One of these latter cases, described by Hamilton and Tait,3 corresponded to a metastasis. The other, described by Graham et al,11 had anamnesis that included surgical removal of a paraganglioma in a different localization, leading to the hypothesis that the thoracic lesion was probably a metastatic dissemination or a multicentric growth. A similar observation was made in a case reported by Boker et al.1 For these reasons, these cases of thoracic extradural paraganglioma were excluded from among the primitive ones.

Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of paraganglioma cannot be based on imaging features. On CT scans, in fact, such lesions appear as homogeneous masses, sometimes with calcifications, and they present homogeneous enhancement due to their rich vascularization.12, 13 Areas of osteolysis or even pathological fractures and/or enlargement of the vertebral foraminae are often observed.1, 13, 15 Osteocondensant forms have rarely been described and may also be found in the adjacent costs.12

On MRI, paragangliomas appear hypo-iso-intense on T1 and iso-hyper-intense, often with a ‘salt & pepper’ appearance on T2-weighted images. They present an intense homogeneous gadolinium-enhancement. They may be distinguished from more malign lesions on MRI when thecal compression and dislocation are present instead of infiltration.15

The most specific diagnostic technique is mIBG (m-[123I] iodobenzylguanidine) scintigraphy, even if its use has been limited to secernent lesions or for the research of synchronous or metachronous metastasis.11, 13 Further to imaging features leading to paraganglioma, mIBG scintigraphy may be another confirmation. Yet, definitive diagnosis is possible only by means of the histological exam.

The differential diagnosis of paragangliomas includes ganglio-neural tumors (schwannomas, ganglioneuromas), secondary lesions, and all the mediastinic tumors, for extradural thoracic lesions. Compared to mielomas or metastasis, paraganglioma vascularization is not only rich but also homogeneous. Hemangiomas are differentiated due to cortical expansion and a trabeculous ‘honeycomb’ aspect. Angiomiolipomas present fat cumulus.15

Macroscopically, paragangliomas are characterized by a rosy–red to brown color, seldom hemorrhagic. Microscopically, the principal Type I cells (polygonal, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, sometimes presenting granules grouped in nests, so-called ‘zellballen’) are found surrounded by sustaining Type II cells. Mitosis is rare and the pleomorphism is limited. A narrow and rich vascular net is often found. Degenerative, calcific, cystic, hemorrhagic, and/or necrotic areas are also sometimes found at times. Immunohistochemical colorations are essential for a secure diagnosis. The most important neuroendocrin markers are chromogranine and sinaptofisine that identify Type I cells and S-100 protein that identifies Type II cells.4

To reduce the risk of recurrence, radical surgical removal is mandatory. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have minor efficacy and are often used palliatively in cases of aggressive or multicentric paragangliomas or when the patient conditions cannot tolerate surgery. Best results were obtained with I131-mIBG chemotherapy: interruption of disease progression, clinical improvement and less captation on scintigraphy.13

Postsurgical radiotherapy is also used in cases of recurrence or after resection of metastasis.3

The most frequently described surgical approaches in the treatment of mediastinic lesions invading the vertebrae are anterior or double approaches (anterior and posterior) in one or two sessions.17, 18, 19, 20

In the presented case, the surgical treatment was performed in one session, with the patient prone. The posterolateral approach allowed complete removal of the lesion with anterior and posterior monolateral stabilization.

Conclusions

Thoracic epidural paragangliomas are rare but have to be considered in the differential diagnosis of thoracic/mediastinal lesions since they present a better postsurgical prognosis with respect to malign lesions, more frequently encountered in this area.

Imaging features, typical of benign lesions, are good primary elements of differentiation but histological examination is necessary for a definitive diagnosis.

Surgical removal is the gold standard treatment and has to be total, possibly ‘en bloc’.

References

Boker DK, Wassmann H, Solymosi L . Paragangliomas of the spinal canal. Surg Neurol 1983; 19: 461–468.

Djindjian M, Ayache P, Brugières P, Malapert D, Baudrimont M, Poirier J . Giant Gangliocitic paraganglioma of the filum terminale. Case report. J Neurosurg 1990; 73: 459–461.

Hamilton MA, Tait D . Metastatic paraganglioma causing spinal cord compression. Case report. Br J Radiol 2000; 73: 901–904.

Moran CA, Rush W, Mena H . Primary spinal paragangliomas: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases. Histopathology 1997; 31: 167–173.

Pigott TJ, Lowe JS, Morrell K, Kerslake RW . Paraganglioma of the cauda equine: report of three cases. J Neurosurg 1990; 73: 455–458.

Sundgren P, Annertz M, Englud E, Strombland LG, Holtas S . Paragangliomas of the spinal canal. Neuroradiology 1999; 41: 788–794.

Brodkey JA, Brodkey JS, Watridge CB . Metastatic paraganglioma causing spinal cord compression. Spine 1995; 20: 367–372.

Constantini S, Soffer D, Shalit MN . Paraganglioma of the thoracic spinal cord with cerebrospinal fluid metastasis. Spine 1989; 14: 643–645.

Cybulski GR, Nijenshon E, Brody BA, Meyer PR, Cohen B . Spinal cord compression from a thoracic paraganglioma: case report. Neurosurgery 1991; 28: 306–309.

Fitzgerald LF, Cech DA, Goodman JC . Paraganglioma of the thoracic spinal cord. Case report. Clin Neurol Neuro 1996; 98: 183–185.

Graham JJ, Lee GYF, Wong GTH . Functioning paraganglioma of the thoracic spine: case report. Neurosurgery 2003; 53: 992–995.

Houten JK, Babu RP, Miller DC . Thoracic paraganglioma presenting with spinal cord compression and metastases. J Spinal Disord Techn 2002; 15: 319–323.

Noorda RJP, Wuisman PIJM, Kummer AJ, Winters HA, Rauwerda JA, Egeler-Peerdeman SM . Non functioning malignant paraganglioma of the posterior mediastinum with spinal cord compression. A case report. Spine 1996; 21: 1703–1709.

Reyes MG, Fresco R, Bruetman ME . Mediastinal paraganglioma causing spinal cord compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1977; 40: 276–279.

Shin JY, Lee SM, Hwang MY, Sohn CH, Suh SJ . MR findings of spinal paraganglioma: report of three cases. J Korean Med Sci 2001; 16: 522–526.

Lang FF, Epstein FJ, Ransohoff J, Allen JC, Wisoff J, Abbott IR, Miller DC . Central nervous system gangliogliomas. Part II: clinical outcome. J Neurosurg 1993; 79: 867–873.

Grunenwald D, Mazel C, Girard Ph, Berthiot G, Dromer C, Baldeyrou P . Total vertebrectomy for en bloc resection of lung cancer invading the spine. Ann Thoracic Surg 1996; 61: 723–726.

Han PP, Dickman CA . Thoracoscopic resection of thoracic neurogenic tumors. J Neurosurg 2002; 96: 304–308.

Han PP, Kenny K, Dickman CA . Thoracoscopic approaches to the thoracic spine: experience with 241 surgical procedures. Neurosurgery 2002; 51(suppl 2): 88–95.

Seol HJ, Chung CK, Kim HJ . Surgical approach to anterior compression in the upper thoracic spine. J Neurosurg 2002; 97: 337–342.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conti, P., Mouchaty, H., Spacca, B. et al. Thoracic extradural paragangliomas: a case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord 44, 120–125 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101796

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101796

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of primary spinal paragangliomas

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2015)