Abstract

The end-Ordovician was an enigmatic interval in the Phanerozoic, known for massive glaciation potentially at elevated CO2 levels, biogeochemical cycle disruptions recorded as large isotope anomalies and a devastating extinction event. Ice-sheet volumes claimed to be twice those of the Last Glacial Maximum paradoxically coincided with oceans as warm as today. Here we argue that some of these remarkable claims arise from undersampling of incomplete geological sections that led to apparent temporal correlations within the relatively coarse resolution capability of Palaeozoic biochronostratigraphy. We examine exceptionally complete sedimentary records from two, low and high, palaeolatitude settings. Their correlation framework reveals a Cenozoic-style scenario including three main glacial cycles and higher-order phenomena. This necessitates revision of mechanisms for the end-Ordovician events, as the first extinction is tied to an early phase of melting, not to initial cooling, and the largest δ13C excursion occurs during final deglaciation, not at the glacial apex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shelf sedimentary architecture is controlled essentially by relative rates of base-level change and sediment supply1,2. The base level reflects the interplay between tectonics (subsidence, volume change at mid-oceanic ridges) and the orbitally tuned, glacio-eustatically driven, sea-level change. The rate of the latter, at tens of metres per 104–105 years, is one to three orders of magnitude greater than the tectonically driven sea-level change, at tens of metres per million years or less. The critical issue for analysing the stratigraphic record, therefore, is the correct assignment of depositional units to their appropriate temporal hierarchy alongside a given sea-level curve. Another consideration is the temporal significance of the observed or suspected hiatuses. Any stratigraphic record of ancient shelf deposits, and their isotopic or palaeontological proxies, inevitably samples only the discontinuous segments of a given sea-level curve3, which often are below the relatively coarse resolution correlation potential of Palaeozoic biostratigraphy4. Regardless, shelf deposits are the principal record that we have for pre-Mesozoic glaciations and they must therefore serve as stratigraphic archives for glacially driven events, providing: subsidence was active; water depths at the onset of glaciation were moderately deep; and sediment supply was adjusted to subsidence rates. These preconditions are essential for the maintenance of significant water depths during glaciation, as any rapid shallowing would pre-empt the registration of subsequent glacio-eustatic events.

The end-Ordovician witnessed one of the three largest Phanerozoic glaciations with the development of continental-scale ice sheets5,6,7. This climatic event was postulated to have been initiated by massive weathering of fresh volcanic rocks8, tectonics and related plate motions9,10,11, high cosmic ray flux impacting cloud albedo12 or by a combination of the above13. The glaciation apparently coincided with highly14 or moderately10,15 elevated CO2 levels, with large isotopic excursions (C, S, O, N, Nd), and with a major double-phased biological extinction16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Interpretations based on far-field, low palaeolatitude sequences, resulted in ‘coup-de-théâtre’ scenarios that have tied the two phases of extinction to the onset and termination of a single glaciation16,17,21. Yet the high palaeolatitude near-field sequences contain up to five glacial cycles that can be tentatively correlated across the Gondwanan glaciated platforms5,23. The low palaeolatitude archives must therefore represent a more complex scenario18,22,24,25,26 than that of a single, major glacial event. If so, a multiorder climate signal with a hierarchy of cycles, a Cenozoic-type ‘business as usual’ scenario, is a more likely alternative than a large singular event. Such linkage of eustatic, biological and isotopic records to the climatically forced development of an ice sheet can only be contemplated within a framework of high-resolution sequence stratigraphy that integrates allo-, chemo- or biostratigraphic markers.

Here, we present such a framework, based on the recognition of genetic stratigraphic sequences (GSSs) and intervening erosion surfaces (see Methods). This framework, driven by glacio-eustatic cycles tied to the evolution of polar continental-scale ice sheets over west Gondwana5, enables the correlation of eustatic cycles at a level that is beyond the resolution capability of most absolute dating methods and of biozones, the latter typically of Myr duration4. A Cenozoic-style scenario including three main glacial cycles and higher-order phenomena necessitates the revision of the end-Ordovician, glaciation-related sequence of events.

Results

Palaeolatitude sequence stratigraphic frameworks

We introduce sequence stratigraphic correlation frameworks for two superbly exposed and exceptionally well-developed latest Ordovician successions (Fig. 1), the Anti-Atlas of Morocco7,27,28 and Anticosti Island in Canada25,29. Both offer sections, on a 100-km scale, from the basin edge to the axis of active sedimentary depocentres (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). Relative to the end-Ordovician ice-sheet centre (present-day north-central Africa), they provide a near-field (Anti-Atlas, siliciclastic platform) and a far-field (Anticosti Island, mixed carbonate and siliciclastic) stratigraphic record. These two successions, up to 300 and 100 m thick, respectively, were deposited in basins with notable subsidence rates and significant (ca. 100 m) initial Katian water depths, enabling the development of comprehensive archives of the latest Ordovician glaciation (Supplementary Fig. 3). On the basis of average shelf-depositional rates within the overall Late Ordovician context7,27, and on comparison with analogous late Cenozoic shelf stratigraphies3,30, such thick successions are considered to be long-term >>100s kyr archives. In both areas, the end-Ordovician comprises three genetic low-order stratigraphic sequences (GSSs) of highest significance that, in turn, encompass a number of higher-order GSSs of intermediate and low significance (Fig. 2; see the Methods).

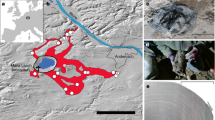

(a) Position of the two study areas on a palaeogeographic reconstruction (modified from Achab and Paris56). In the Late Ordovician, the Anti-Atlas succession was part of the North Gondwana shelf, an epicratonic domain at high palaeolatitudes (green star). It included an actively subsiding depositional trough, which was free of ice until the middle Hirnantian, but glaciated during the glacial maximum in the upper Hirnantian. In contrast, the Anticosti Island succession accumulated in a foreland basin that developed at low palaeolatitudes during closure of the Iapetus Ocean at the onset of the Taconic orogeny (orange star). (b) On Anticosti Island, cliffs and marine platforms provide a superbly exposed latest Ordovician to early Silurian mixed siliciclastic–carbonate shelf succession. At Pointe Laframboise, alternating limestone (inner ramp) and softer shale (outer ramp) intervals across the shoreline platform clearly reflect the sequence stratigraphic correlation scheme inferred from sedimentary facies analysis. (c) Extensive outcrops of the Anti-Atlas Palaeozoic succession offer a superb record of predominantly shallow-marine Cambrian to Carboniferous sequences27,65. Near Tazzarine, a thick (up to 350 m) succession of alternating sandstones (storm- to tide-dominated, subordinate glaciation-related deposits) and offshore shales allows a compelling sequence stratigraphic correlation framework to be established for the latest Katian and Hirnantian (see Fig. 2). Coloured triangles represent the three identified Late Ordovician Glacial Cycles (LOGC1–3) that comprise a lower, orange/yellow triangle (regressive system tracts, RSTs) and an upper, purple triangle (transgressive system tracts, TSTs). LOGC are bounded by dotted lines, underlining MFS. Other surfaces: dashed lines, sharp-based surfaces and their correlatives within RSTs; solid lines, maximum regressive surfaces; wavy lines, subaerial erosion (Anticosti) or basal glacial erosion surface (Anti-Atlas).

The two frameworks were established separately and later correlated (note the different vertical scales: 50 m and 100 unit bars for the Anti-Atlas and Anticosti Island successions, respectively). Both show three superposed low-order GSSs that comprise alternating RST and TSTs symbolized by coloured, orange/yellow and purple triangles, respectively. These low-order GSSs include higher-order GSSs (high- and highest-order GSSs) of intermediate and low significance, symbolized by smaller triangles (white and grey triangles, respectively). Apparent intercontinental correlation of the two sequence stratigraphic frameworks for low- and high-order ranks confidently supports the proposition that the low-order GSSs are signatures of three successive LOGCs, which together encompass a 2–4 Myr latest Katian to lowermost Silurian time interval. Because the high- and highest-order GSSs relate to the relative rates of base-level changes (Supplementary Fig. 3), rather than to a priori assumptions about sequence duration, no temporal significance can be attributed at this stage. We retain here lithostratigraphic names because the related boundaries crosscut timelines, for example, the Katian/Hirnantian boundary (see Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). Lf: Laframboise Member. Black arrows point to stratigraphic interval with significant faunal turnovers. Encircled numbers 1–6 refer to the numbering of glacial erosion surfaces (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

The intercontinental correlation of these two successions is made possible due to the recognition of marker intervals. Earlier palaeontological studies already bracketed the stratigraphic interval that contains the well-known end-Ordovician extinction events (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). In both sections, the first extinction event is situated around the conventional Katian–Hirnantian boundary, which in our record is penecontemporaneous with the major bounding surface that separates the two lower low-order GSSs. The related ‘maximum flooding interval’—rather than the maximum flooding surfaces (MFS) that cannot be strictly synchronous at the global scale—is our first marker. It correlates with the brief ‘pre-Hirnantian deepening’ event identified in western Laurentia22. The second marker based on allostratigraphy relies on the signature of the end-Ordovician glacial climax. In the Anti-Atlas, it demonstrably correlates with the stratigraphic interval bounded by glacial erosion surfaces and includes widespread glacial (subglacial, glaciomarine…) deposits in the basinal succession (the glacial interval in Fig. 2). Note that coeval strata are often absent in basin edge successions (Hajguig Wadi log in Fig. 2). In the Anticosti Island succession, the signature of the glacial climax (lowest sea levels) is ascribed to the prominent erosional unconformity at the base of the Laframboise Mb. The result is a severe erosional truncation of the studied interval (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Regional correlation of low- and high-order GSSs between these two markers is indeed intriguing (Fig. 2). Moreover, other subordinate erosional unconformities at the basin edge of the Anti-Atlas succession have their counterparts in the Anticosti Island succession. For the highest-order GSSs, at least partially related to local processes, such correlations are less reliable.

The end-Ordovician glacial tempos

Within the context of glaciation, where eustasy is expected to control shallow shelf sequences3, our findings strongly suggest that the two independent regional scale frameworks and their correlation are robust and that the correspondence of the low- and high-order GSS records from dissimilar tectonic and environmental settings arises from glacio-eustatically fluctuating sea levels, the latter a consequence of waxing and waning of the western Gondwana ice sheet. We interpret the three low-order GSSs to be the signature of the three extensive glacial cycles (Latest Ordovician Glacial Cycles, LOGCs 1–3; Figs 2 and 3 and Supplementary Note). Note that our provisional numbering refers to the latest Ordovician, understood to informally include the highest Katian and the Hirnantian. This is in agreement with the views that ice sheets were extant already before the latest Katian7,22,31,32. Our first glacial cycle spans the upper Katian (LOGC 1), the second (LOGC 2) includes the uppermost Katian strata and most of the lower to middle part of Hirnantian and the third (LOGC 3) commences in the upper Hirnantian and ends in the lowermost Silurian. In our view, corroborated recently by Nd isotope studies22, the end-Ordovician glaciation could not have been restricted to a single short-lived glacial event, as earlier believed.

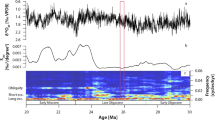

Temporal correspondence between documented (chitinozoa54,55,59,60) or essentially inferred (graptolite) biostratigraphies and (a), the Anticosti Island succession with its related isotopic signal and faunal turnovers and (b), the Anti-Atlas succession with interpreted low-frequency sea-level changes and ice-sheet occurrences. A cycle hierarchy is developed that distinguishes LOGC1–3 (low-order, high-significance Late Ordovician Glacial Cycles represented by both coloured triangles and the thick, pale blue curve) from high-order cycles (thin, dark blue curve). LOGCs are bounded by major MFS (dotted lines). Blue shading highlights time intervals specifically characterized, or thought to be characterized by ice-sheet development stages. The ice-sheet development increased from the late Katian to the late Hirnantian, as suggested by glacioeustatic trends. The dashed blue curve is a representation of the early Silurian eustatic background. Black, dashed lines are the inferred Katian to Hirnantian and Hirnantian to Llandovery boundaries. (c) Representation of a potential time calibration is based on astronomical forcings dominated by 1.2 Myr amplitude modulation of obliquity cycles34 (see text for details). By analogy with the Cenozoic, the composite artificial curve was constructed by mixing high-frequency orbital cycles (‘ETP’ for eccentricity–tilt–climatic precession33) and here it is shown only to illustrate the distortion in the stratigraphic record. It results in condensed transgressive and overdeveloped lowstand intervals, relative to a linear timescale. The high- and highest-order glacial cycles likely correspond to such orbitally forced, high-frequency climatic oscillations. In contrast, during the long interglacials orbital forcing did not result in ice-sheet development and they have therefore a poorly differentiated record. The end-Ordovician includes short glaciation intervals with cumulative duration of perhaps a few hundred thousand years. The embedded isotopic and biological signals show up to three discrete isotopic events and two faunal turnovers (oblique-line shading), from the highest Katian to uppermost Hirnantian. The Hirnantian isotopic carbon excursion (HICE) is not restricted to the excursion associated with LOGC 3 at the top of the Ellis Bay Fm. The dashed pink curve is a representation of the Katian istopoic background.

The minimum depositional time for the entire LOGC 1–3 succession is in excess of the Hirnantian duration (~1.4±0.2 Myr33), the latter encompassing about 60–90% of the LOGC 2 and some 40–80% of the LOGC 3. Assuming that all LOGCs are of about equal durations, a single LOGC corresponds to a 0.7–1.6 Myr time span. The embedded higher-frequency multiorder event stratigraphy is typical of orbitally controlled climatic oscillations that lead to recurring ice-sheet growth stages34, in agreement with the modelling results of Hermann et al.35 Note however that in contrast to the well-known, strongly asymmetric and shorter-term, Pleistocene glacial cycles36, our LOGCs show no abrupt deglaciations. They have a symmetric distribution of the high-order GSSs, as evident from the stacking patterns within the low-order regressive to transgressive system tracts (TSTs). Long-lasting interglacials are expressed as condensed, maximum flooding stratigraphic intervals7 that account for significant portions of the overall duration of the studied time span (Fig. 3). Despite of some similarities to Quaternary glaciations5,7,15,31,37, the durations and internal organization of LOGCs argue for dissimilar glacial tempos and forcings. These Ordovician features and tempos more closely resemble the Oligocene climate patterns that were driven by a high-amplitude obliquity modulation at 1.2 Myr frequency34, resulting in a limited number of short-lived ice-sheet growth phases, our high-order GSSs, centred around the obliquity nodes38,39. Such high-frequency signals may hold some similarities to the metre-scale cycles described from other low-latitude areas and attributed to ≈200 (ref. 40) or 40–130 kyr (ref. 32) frequency oscillations.

Assuming the analogy with the Oligocene climate is valid, we hypothesize that an orbital forcing responding to the amplitude modulation of the obliquity typifies glacial climate systems at relatively high CO2atm levels. In such a scenario, the ice-sheet inception, driven by ice-albedo feedbacks, may have resulted from a dearth of exceptionally warm rather than a ubiquity of exceptionally cool summers38.

Discussion

Our sequence stratigraphic framework allows Hirnantian excursion(s) and extinction(s) to be revisited. The large positive carbon isotope excursions of the Palaeozoic, such as the Hirnantian Isotopic Carbon Excursion, HICE in LOGC 3 (refs 17, 18, 41, 42, 43), are often used as chronostratigraphic markers, albeit with no consensus model for their existence. Yet, the notion that the δ13Ccarb signal of shelf carbonates is a direct reflection of the δ13CDIC of the globally uniform open ocean is clearly open to debate13,26 (Supplementary Discussion). Note that the magnitude and occurrences of such 13C enrichments depends on localized settings (for example, epeiric versus open ocean aquafacies22,44) and is therefore related to depositional facies and not straightforwardly to a global signal. For example, the δ13Ccarb on the modern Bahamas Bank is considerably more positive than that of the open ocean45.

In addition, our revised chronology questions the paradigm of temporal relationships that link the position of the end-Ordovician glacial cycles, their tempos and biochemical events13,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,26. The first issue that arises is the identification and temporal range of the HICE itself. If it is understood as coeval with the large +4‰ isotopic excursion, it has to be confined to a restricted time interval of a single high-order GSS within the end-Ordovician glaciation (Fig. 3), as posited by the Anticosti case study. If, on the other hand, understood as a 13C signal that commences in the latest Katian and ends in the latest Hirnantian, our results (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1) show 13C enrichments in at least three stratigraphic positions, suggesting that HICE combines several excursions, thus challenging its validity as a high-resolution chronostratigraphic marker.

The Anticosti δ13Ccarb curve (Fig. 3) includes two main isotopic events. First, it is the well-known excursion in the Laframboise Mb. (+4‰) that is disconnected from a rising limb in the underlying strata by a major unconformity that we relate to the glacial maximum and to subaerial erosion in LOGC 3. Second, there is an earlier asymmetric excursion (+2‰) with its descending limb that is spanning the lower and middle parts of the Ellis Bay Fm. (LOG 2). There is also a lesser enrichment in the uppermost Vauréal Fm., associated with LOGC 1, which may form a third, subordinate excursion. Other putative (<1‰) excursions, while present, are minor and difficult to interpret. This multi-peak isotope pattern at Anticosti Island questions the views of strictly synchronous signals, despite observations that a number of Hirnantian records worldwide—and potentially similar ‘wiggles’ in the carbon isotope record elsewhere—contain positive δ13C spikes that appear isochronous17,24,46 within the correlation capabilities of the Palaeozoic bio- and/or chronostratigraphy26. An apparent single peak may represent only disjointed parts (Fig. 4) of a hypothetically complete δ13Ccarb curve for just one of several repetitious LOGCs, or a composite signal from an artificially stacked section.

(a) The main lithostratigraphic units on Anticosti Island, including the Laframboise Member, are shown with their representative depositional facies and related δ13C curve. They are separated by shoreline ravinement unconformities62. The sequence stratigraphic interpretation differentiates low-order/high-significance regressive (orange and yellow triangle) and transgressive (purple triangle) system tracts. The corresponding first-order unconformity coincides with the base of the Laframboise Member. High-order cycles represented by white triangles are present in the LOGC 3 TST, which commences with the base of the Laframboise Member. (b) The same sequence in the ‘linear’ timescale perspective of this succession of depositional events. It includes relatively long depositional hiatuses (oblique-line shading). At Anticosti, the high-frequency glacio-eustatic sea level changes, similar to those recorded in the near-field glacial record of Morocco, are represented by unconformities coeval with the glacial maxima. One recorded interglacial event (Laframboise Mb.) is interpreted here as a single high-order GSS within the larger TST of LOGC 3. (c) An alternative view of the isotopic excursion, which includes the stratigraphic hiatuses. The δ13C record captures only disjointed segments of the isotope signal. In particular, the δ13C curve does not include values from the time interval that corresponds to the Hirnantian glacial climax. We suspect that the trend from background levels to the maximum in fact combines an initial rise that predates the glacial climax, the associated hiatus and the subsequent maximum that postdates the glacial climax. This maximum is developed mainly within the reefal limestones constituting the highstand facies of a particular high-order GSS.

Whatever the temporal extent of HICE, our sequence stratigraphic framework warrants reconsideration of the published ‘cause-and-effect’ scenarios for its origin. The rising limb of the 13C excursion at the base of the Ellis Bay Fm. (Fig. 3) is associated with a highstand that follows the LOGC 1–2 transition, while its descending limb spans several high-frequency glacio-eustatic cycles within the late regressive to TSTs of the LOGC 2. In this case, there is therefore no apparent connection between eustasy and the δ13Ccarb curve. The simplest explanation is to see the LOGC 2 isotopic signal as that of regional epeiric water masses with their distinctive variations in δ13C (ref. 44). In contrast, the subsequent, exceptionally high-amplitude excursion is within the TST of LOGC 3, and is associated with a drastic basin-scale change of facies caused by transition from glacial to warmer climates (reefs of the Laframboise Mb.). At a higher resolution, the excursion appears to be confined to the highstand of a high-order GSS (Fig. 4), thus peaking at times of rising sea levels associated with deglaciation. This coincidence is opposite to the postulated lowstand conditions that are essential in the ‘weathering’ scenario11 and the model can be discounted as a potential explanation. The ‘productivity’47 and related ’circulation pattern’ explanations48,49 could perhaps offer plausible alternatives, providing it can be demonstrated that the isotopic excursion is not facies dependent. Our highstand nadir of isotope excursion can then be consistent with the scenario that invokes carbon storage in the deeper parts of the shelf39, albeit constrained—because of it high amplitude—to basinal, not global, scales (see box model in Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). In such a context, the particular highstand conditions favourable for the development of carbon excursions may arise at distinct locations during any high-order GSSs. If so, it is the short duration of contiguous high-order GSSs that give the impression of a synchronous, worldwide phenomenon during the LOGC 3 transgressive trends. For minor excursions, such as those in LOGC 1 or in the uppermost (below the unconformity) Ellis Bay Fm., we contend that our present-day knowledge of carbon isotope systematics does not permit unique diagnostics of causative factors and scenarios. We therefore desist from their interpretation.

In summary, providing our sections represent sufficiently comprehensive archives of the latest Ordovician development, we dispute the apparent association of each LOGC with an individual isotopic excursion. At higher resolution, the relationship with sea-level history differs from case to case, indicating that it is not a unique forcing but likely a combination of processes that is involved in 13C enrichment21.

Similar reasoning may suggest that ‘pulses’ in patterns of the end-Ordovician biological extinction result from telescoping of segments from the stratigraphic record, as must be the case for hiatus-dominated successions20. The two phases of the Late Ordovician mass extinction that were documented worldwide in earlier studies17,21 are however confirmed also by our results on the Anticosti Island (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Our correlation framework moreover indicates that these turnovers are relatively long-lasting time intervals that encompass several glacio-eustatic fluctuations of the high or highest GSSs in the Anti-Atlas record. Whether these turnovers originate from evolution specifically related to LOGC developments, or whether they only mirror a succession of stacked, quasi-instantaneous, pulses is beyond resolution of our data set, regardless of their potential combination within protracted, global events21,50. The ensemble of our sections studied represents only a fraction of affected palaeohabitats and biota, and, as explained, sections that contain complementary palaeontological data cannot be readily correlated into our framework; our analyses thus likely undersamples the full biotic dynamics through this interval. Yet, our juxtaposition of extinction phases to glacial development suggests a more nuanced scenario than previously advocated (Fig. 3).

The older turnover, which has classically been associated with the onset of the Hirnantian glaciation at the base of the N. extraordinarius Biozone, spans an interval that includes LOGC 1 deglaciation and the early LOGC 2 highstand. This turnover corresponds therefore mostly to the first major interglacial period. The models that are based on processes linked to glacial onset, such as the shrinkage of biotic ecospace, temperature decline or development (or the loss) of anoxia during falling sea level13,15,20,21, are thus not compatible with this revised scenario. Instead, processes linked to deglaciation dynamics (for example, amplification of meltwater fluxes that enhance ocean stratification), or flooding of the shelves by relatively deep anoxic waters13,21,51, appear to be more likely scenarios for this first turnover, but they are not applicable, as previously envisioned, for the second turnover. The second turnover that we recognize in LOGC 3 is an event traditionally assigned to the lower part of the N. persculptus Biozone. This extinction/recovery pattern affects mostly macrofauna in the Anticosti Island succession (Supplementary Fig. 2). The phytoplankton crisis, on the other hand, commenced beneath the regional unconformity (Fig. 4), that is before glacial climax of LOGC 3 (refs 42, 52), suggesting that the second end-Ordovician faunal turnover may have been initiated already during the late Hirnantian ice-sheet waxing, thus casting doubt on a unique causative linkage that would have been confined to final deglaciation. Note nevertheless that the ubiquitous existence of worldwide hiatuses at that time makes any interpretation tentative.

While we appreciate the merits of a sophisticated model-driven approach, and welcome the impetus derived from it, the insights arising here from the application of basic geological methods underline the need for detailed understanding of the rock record as well13. In this contribution, temporal relationships of near-field and far-field records for the end-Ordovician glaciation are considered within a high-resolution, multiorder correlation framework that reflects a Cenozoic-style hierarchy of glacio-eustatically driven oscillations consisting of three main cycles and superimposed higher-order subcycles. This interpretation questions earlier views that were based on lower resolution data sets for a simple latest Katian decline in sea level followed by its rise in the upper Hirnantian. An oversimplified sedimentary succession likely incorporates significant hiatuses and represents only a partial record of the entire time interval18,53. Frequently, such stratigraphic sections correspond to vertically juxtaposed, unrelated parts of glacial cycles, resulting in biased timing of biochemical signals relative to the glacial tempos. On the basis of our framework, we anticipate that the most easily captured phases in the worldwide end-Ordovician development should reflect the initial waxing stage and potentially the immediately ensuing flooding event (LOGC 1), followed by later reflooding of the shelves at the end of LOGC 3. In more comprehensive successions, the maximum flooding interval at the LOGC 2-3 transition (mid-Hirnantian transgression5) will likely yield a decipherable signature22.

The orbitally controlled depositional record of a glacial interval will mostly be underrepresented in proven or suspected hiatuses. These may originate from nondeposition, subaerial or subglacial unconformities, transgressive post-glacial ravinement processes, mass movements or from erosion by bottom currents, the latter being particularly effective for the deeper parts of shelf basins. Due to the lack of Palaeozoic deep-sea records, the absolute timing and calibration of the Ordovician glaciation may remain enigmatic13. We envision therefore that future progress in understanding the temporal, spatial and causal evolution of the Late Ordovician environmental record will have to rely on high-resolution methods that capture multiorder sequence stratigraphy and related proxies along depositional profiles on a regional scale. Our advances using these methods include: rejection of the earlier cause-and-effect scenarios for HICE(s), as these no longer fit with the revised context of glacial/ glacio-eustatic development; the suggestion that low-order LOGCs likely represent the 1.2 Myr long obliquity cycles that modulated ice-sheet dynamics, similar to scenarios proposed for the Oligocene; and the insight that the first Hirnantian extinction pulse, contrary to earlier studies, was linked to an intervening melting phase, not to the initial cooling phase of the end-Ordovician.

Methods

GSSs

Sequence stratigraphic correlation frameworks are based on visual correlations of marker beds along continuous exposures at the 10–30 km scale (Fig. 2) and on refined, regional scale, chitinozoan-based biostratigraphies for northern Gondwana54,55,56,57,58 and eastern Laurentia59,60. This results in correlations that are noticeably different from lithostratigraphic schemes (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). MFS and a variety of erosion surfaces have been delineated in the field. The MFS coincide with deeper, usually condensed, depositional conditions and serve as bounding surfaces for GSSs61, ideally including a lower regressive system tract (RST) and an upper transgressive system tract (TST). Erosional surfaces correspond to glacial erosion surfaces (Morocco); subaerial unconformities reworked by transgressive ravinement processes (SR-U sensu Embry, 2009 (ref. 62); Anticosti); or sharp-based erosional surfaces punctuating regressive facies trends and ascribed in most cases to regressive surfaces of marine erosion (Anti-Atlas and Anticosti). We favour GSSs over Trangressive/Regressive62 (T–R), or depositional sequences2 because their bounding surfaces (MFS) better approximate late deglaciation conditions and thus appropriately bracket glacial cycles. In this scheme, a post-glacial highstand of an interglacial is represented by deposits that constitute the lower part of the subjacent sequence.

Sequence hierarchy

Stratigraphic surfaces have been assigned to a hierarchy of GSSs. The significance of facies shifts and/or their penetration into the basin are used as criteria to assess the relative magnitude of base-level falls in successive, multiorder sequences. It results in a data-driven hierarchy62, different from a frequency-related scheme based on a priori assumptions about durations of sequences. The highest-order (low significance) GSSs display limited facies shifts, both in the basin and at basin edge. More significant are the high-order genetic sequences, which comprise several highest-order GSSs and/or include abrupt facies shifts associated with coeval, or at least suspected, erosion surfaces at basin edge. The low-order sequences (highest significance) are made up of a suite of high-order sequences, the stacking pattern of which defines long-term RST and TST. They are bounded by the major MFS associated with severe condensation (for example, phosphogenesis in the Anti-Atlas). They include in their most regressive part (late RST or early TST) one or several important erosional surfaces such as shoreline ravinement unconformities, or glacial erosion surfaces in the upper Hirnantian in Morocco, which expand toward basinal areas. This approach is often not appropriate for maximum flooding intervals characterized by relatively deep depositional conditions, where facies shifts are poorly deciphered. Here, an alternative, frequency-related, hierarchy is frequently applied7.

Base-level falls associated with glacial erosional surfaces are recognized on the basis of: their basinward extent at regional scale63 (Supplementary Fig. 1); the development/absence of well-organized subglacial shear zones that indicate fully subglacial/marginal ice fronts64. Maximum erosional depths are not considered to be a measure of the significance of a glacial surface. We are aware that such estimates reflect glacial extents rather than true ice-sheet volumes, but they do have significance when dealing with high- and low-order GSSs.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ghienne, J.-F. et al. A Cenozoic-style scenario for the end-Ordovician glaciation. Nat. Commun. 5:4485 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5485 (2014).

References

Jervey, M. T. inSea Level Changes—An Integrated Approach Vol. 42, eds Wilgus C. K.et al. 47–69Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Special Publication (1988).

Catuneanu, O. et al. Towards the standardization of sequence stratigraphy. Earth-Sci. Rev. 92, 1–33 (2009).

Mountain, G. S. et al. inContinental Margin Sedimentation: From Sediment Transport to Sequence Stratigraph Vol. 37, eds Nittrouer C. A.et al. 381–458International Association of Sedimentologists, Special Publication, Blackwells (2007).

Sadler, P. M., Cooper, R. A. & Melchin, M. High-resolution, early Paleozoic (Ordovician-Silurian) time scales. GSA Bull. 121, 887–906 (2009).

Ghienne, J.-F., Le Heron, D., Moreau, J., Denis, M. & Deynoux, M. inGlacial Sedimentary Processes and Products Vol. 39, eds Hambrey M.et al. 295–319International Association of Sedimentologists, Special Publication, Blackwells (2007).

Le Heron, D. P. & Craig, J. First-order reconstructions of a Late Ordovician Saharan ice sheet. J. Geol. Soc. 165, 19–29 (2008).

Loi, A. et al. The Late Ordovician glacio-eustatic record from a high latitude storm-dominated shelf succession: the Bou Ingarf section (Anti-Atlas, Southern Morocco). Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 296, 332–358 (2010).

Lefebvre, V., Servais, T., François, L. & Averbuch, O. Did a Katian large igneous province trigger the Late Ordovician glaciation? A hypothesis tested with a carbon cycle model. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 296, 309–319 (2010).

Herrmann, A. D., Patzkowsky, M. E. & Pollard, D. The impact of paleogeography, pCO2, poleward ocean heat transport, and sea level change on global cooling during the Late Ordovician. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 206, 59–74 (2004).

Nardin, E. et al. Modeling the early Paleozoic long-term climatic trend. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 123, 1181–1192 (2011).

Kump, L. R. et al. A weathering hypothesis for glaciation at high atmospheric pCO2 during the Late Ordovician. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 152, 173–187 (1999).

Shaviv, N. J. & Veizer, J. Celestial driver of Phanerozoic climate? GSA Today 13/7, 4–10 (2003).

Melchin, M. J., Mitchell, C. E., Holmden, C. & Štorch, P. Environmental changes in the Late Ordovician–early Silurian: Review and new insights from black shales and nitrogen isotopes. GSA Bull. 125, 1635–1670 (2013).

Royer, D. L. CO2-forced climate thresholds during the Phanerozoic. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5665–5675 (2006).

Vandenbroucke, T. R. A. et al. Polar front shift and atmospheric CO2 during the glacial maximum of the Early Paleozoic Ice-house. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14983–14986 (2010).

Sheehan, P. M. The Late Ordovician mass extinction. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 29, 331–364 (2001).

Brenchley, P. J. et al. High-resolution stable isotope stratigraphy of Upper Ordovician sequences: Constraints on the timing of bioevents and environmental changes associated with mass extinction and glaciation. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 115, 89–104 (2003).

Bergström, S. M., Saltzman, M. R. & Schmitz, B. First record of the Hirnantian (Upper Ordovician) δ13C excursion in the North American Midcontinent and its regional implications. Geol. Mag. 143, 657–678 (2006).

Finnegan, S. et al. The magnitude and duration of Late Ordovician-Early Silurian glaciation. Science 331, 903–906 (2011).

Finnegan, S., Heim, N. A., Peters, S. E. & Fisher, W. W. Climate change and the selective signature of the Late Ordovician mass extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6829–6834 (2012).

Harper, D. A. T., Hammarlund, E. U. & Rasmussen, C. M. Ø. End Ordovician extinctions: a coincidence of causes. Gondwana Res. 25, 1294–1307 (2013).

Holmden, C. et al. Nd isotope records of late Ordovician sea-level change— Implications for glaciation frequency and global stratigraphic correlation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 386, 131–144 (2013).

Sutcliffe, O. E., Dowdeswell, J. A., Whittington, R. J., Theron, J. N. & Craig, J. Calibrating the Late Ordovician glaciation and mass extinction by the eccentricity cycles of the Earth’s orbit. Geology 23, 967–970 (2000).

Melchin, M. J. & Holmden, C. Carbon isotope chemostratigraphy in Arctic Canada: Sea-level forcing of carbonate platform weathering and implications for Hirnantian global correlation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 234, 186–200 (2006).

Desrochers, A., Farley, C., Achab, A., Asselin, E. & Riva, J. F. A far-field record of the end Ordovician glaciation: the Ellis Bay Formation, Anticosti Island, Eastern Canada. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 296, 248–263 (2010).

Delabroye, A. & Vecoli, M. The end-Ordovician glaciation and the Hirnantian Stage: a global review and questions about Late Ordovician event stratigraphy. Earth-Sci. Rev. 98, 269–282 (2010).

Destombes, J., Hollard, H. & Willefert, S. inLower Palaeozoic of North-western and West Central Africa ed. Holland C. H. 91–336John Wiley (1985).

Le Heron, D. Late Ordovician glacial record of the Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Sediment. Geol. 201, 93–110 (2007).

Long, D. G. F. Tempestite frequency curves: a key to Late Ordovician and Early Silurian subsidence, sea-level change, and orbital forcing in the Anticosti foreland basin, Quebec, Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 44, 413–431 (2007).

Janszen, A., Spaak, M. & Moscariello, A. Effects of the substratum on the formation of glacial tunnel valleys: an example from the Middle Pleistocene of the southern North Sea Basin. Boreas 41, 629–643 (2012).

Vandenbroucke, T. R. A. et al. Ground-truthing Late Ordovician climate models using the paleobiogeography of graptolites. Palaeoceanography 24, PA4202 (2009).

Elrick, M. et al. Orbital-scale climate change and glacioeustasy during the early Late Ordovician (pre-Hirnantian) determined from δ18O values in marine apatite. Geology 41, 775–778 (2013).

Gradstein, F. M. et al. The Geologic Time Scale Elsevier (2012).

Boulila, S. et al. On the origin of Cenozoic and Mesozoic ‘third-order’ eustatic sequences. Earth-Sci. Rev. 109, 94–112 (2011).

Hermann, A. D., Patzkowsky, M. E. & Pollard, D. Obliquity forcing with 8–12 times preindustrial levels of atmospheric pCO2 during the Late Ordovician glaciation. Geology 31, 485–488 (2003).

Waelbroeck, C. et al. Sea-level and deep water temperature changes derived from benthic foraminifera isotopic records. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 21, 295–305 (2002).

Armstrong, H. A. inDeep Time Perspectives on Climate Change eds Williams M., Haywood A., Gregory F. J., Schmidt D. N. 101–121Special Publication of the Geological Society of London, The Micropalaeontological Society and Geological Society of London, London (2007).

Zachos, J. C., Shackleton, N. J., Revenaugh, J. S., Pälike, H. & Flower, B. P. Climate response to orbital forcing across the Oligocene-Miocene Boundary. Science 292, 274–278 (2001).

Wade, B. S. & Pälike, H. Oligocene climate dynamics. Paleoceanography 19, PA4019 (2004).

Williams, G. E. Milankovitch-band cyclicity in bedded halite deposits contemporaneous with Late Ordovician-Early Silurian glaciation, Canning Basin, Western Australia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 103, 143–155 (1991).

LaPorte, D. F. et al. Local and global perspectives on carbon and nitrogen cycling during the Hirnantian glaciation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 276, 182–195 (2009).

Young, S., Saltzman, M. R., Ausich, W. I., Desrochers, A. & Kaljo, D. Did changes in atmospheric CO2 coincide with latest Ordovician glacial-interglacial cycles? Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 296, 376–388 (2010).

Munnecke, A., Calner, M., Harper, D. A. T. & Servais, T. Ordovician and Silurian sea–water chemistry, sea level, and climate: a synopsis. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 296, 389–413 (2010).

Holmden, C., Creaser, R. A., Muehlenbachs, K., Leslie, S. A. & Bergström, S. M. Isotopic evidence for geochemical decoupling between ancient epeiric seas and bordering oceans: implications for secular curves. Geology 26, 567–570 (1998).

Swart, P. & Kennedy, M. J. Does the global stratigraphic reproducibility of δ13C in Neoproterozoic carbonates require a marine origin? A plio-Pleistocene comparison. Geology 40, 87–90 (2012).

Fan, J., Peng, P. & Melchin, M. J. Carbon isotopes and event stratigraphy near the Ordovician–Silurian boundary, Yichang, South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 276, 160–169 (2009).

Brenchley, P. J. et al. Bathymetric and isotopic evidence for a shortlived Late Ordovician glaciation in a greenhouse period. Geology 22, 295–298 (1994).

Jeppson, L. & Calner, M. The Silurian Mulde Event and a scenario for a secundo-secundo events. T. Roy. Soc. Edin. Earth Sci. 93, 135–154 (2003).

Cramer, B. S. & Saltzman, M. R. Fluctuations in epeiric sea carbonate production during Silurian positive carbon isotope excursions: A review of proposed paleoceanographic models. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 245, 37–45 (2007).

Rasmussen, C. M. O. & Harper, D. A. T. Did the amalgamation of continents drive the end Ordovician mass extinctions? Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 311, 48–62.

Hammarlund, E. U. et al. A sulphidic driver for the end-Ordovician mass extinction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 331, 128–139 (2012).

Delabroye, A. et al. Phytoplankton dynamics across the Ordovician/Silurian boundary at low palaeolatitudes: Correlations with carbon isotopic and glacial events. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 312, 79–97 (2011).

Bergström, S. M., Lehner, O., Calner, M. & Joachimski, M. A new upper Middle Ordovician-Lower Silurian drillcore standart succession from Borenshult in Östergötland, southern Sweden: 2. Significance of δ13C chemostratigraphy. GFF 134, 39–63 (2012).

Bourahrouh, A., Paris, F. & Elaouad-Debbaj, Z. Biostratigraphy, bodiversity and palaeoenvironments of the chitinozoans and associated palynomorphs from the Upper Ordovician of the Central Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Rev. Palaeobot. Palyno. 130, 17–40 (2004).

Webby, B. D., Cooper, R. A., Bergström, S. M. & Paris, F. inThe Great Ordovician Diversification Event eds Webby B. D., Paris F., Droser M., Percival I. 41–47Columbia University Press (2004).

Achab, A. & Paris, F. The Ordovician chitinozoan biodiversification and its leading factors. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 245, 5–19 (2007).

Paris, F. et al. Palynological and palynofacies analysis of early Silurian shales from borehole CDEG-2a in Dor el Gussa, eastern Murzuq Basin, Libya. Rev. Palaeobot. Palyno. 174, 1–26 (2012).

Paris, F. et al. Late Ordovician-earliest Silurian chitinozoans from the Qusaiba core hole (North Central Saudi Arabia) and relation to the Hirnantian glaciation. Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn (in the press).

Achab, A., Asselin, E., Desrochers, A., Riva, J. F. & Farley, C. Chitinozoan biostratigraphy of a new Upper Ordovician stratigraphic framework for Anticosti Island, Canada. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 123, 186–205 (2011).

Achab, A., Asselin, E., Desrochers, A. & Riva, J. F. The end-Ordovician chitinozoan zones of Anticosti Island, Québec: definition and stratigraphic position. Rev. Palaeobot. Palyno. 198, 92–109 (2013).

Galloway, W. E. Genetic stratigraphic sequences in basin analysis. I. Architecture and genesis of flooding-surface bounded depositional units. Amer. Assoc. Petr. Geol. Bull. 73, 125–142 (1989).

Embry, A. F. Practical sequence stratigraphy. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists. at www.cspg.org (2009).

Le Heron, D., Ghienne, J.-F., El Houicha, M., Khoukhi, Y. & Rubino, J.-L. Maximum extent of ice sheets in Morocco during the Late Ordovician glaciation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. Palaeoecol. 245, 200–226 (2007).

Denis, M., Guiraud, M., Konaté, M. & Buoncristiani, J.-F. Subglacial deformation and water-pressure cycles as a key for understanding ice stream dynamics: evidence from the Late Ordovician succession of the Djado Basin (Niger). Int. J. Earth Sci. 99, 1399––1425 (2010).

Burkhard, M., Caritg, S., Helg, U., Robert-Charrue, C. & Soulaimani, S. Tectonics of the Anti-Atlas of Morocco. C. R. Geosci. 338, 11–24 (2006).

Acknowledgements

J.-F.G. and T.R.A.V. acknowledge financial support from the French ‘Agence Nationale de la Recherche’ through grant ANR-12-BS06-0014 ‘SEQSTRAT-ICE’, the CNRS (action SYSTER) and the Regional Council of Nord-Pas de Calais (emergent projects action) in France. This is a contribution to IGCP 591 ‘The Early to Middle Palaeozoic Revolution’. A.D., J.V. and S.W. acknowledge support from NSERC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-F.G., M.-P.D. and A.L. and A.D., C.F., S.W. and J.V. compiled and generated field data, from the Anti-Atlas and the Anticosti Island, respectively. T.R.A.V. and F.P. and A.A. and E.A. generated biostratigraphic data for the Anti-Atlas and the Anticosti Island, respectively. S.W. and J.V. performed isotopic data and ran the C-cycle model. J.-F.G., A.D., T.R.A.V. and J.V. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3, Supplementary Tables 1-3, Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 4074 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ghienne, JF., Desrochers, A., Vandenbroucke, T. et al. A Cenozoic-style scenario for the end-Ordovician glaciation. Nat Commun 5, 4485 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5485

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5485

This article is cited by

-

Characterization of the Gas-Bearing Tight Paleozoic Sandstone Reservoirs of the Risha Field, Jordan: Inferences on Reservoir Quality and Productivity

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2024)

-

Ocean temperatures through the Phanerozoic reassessed

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Low atmospheric CO2 levels before the rise of forested ecosystems

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Vertical decoupling in Late Ordovician anoxia due to reorganization of ocean circulation

Nature Geoscience (2021)

-

Large mass-independent sulphur isotope anomalies link stratospheric volcanism to the Late Ordovician mass extinction

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.