Abstract

Prostate cancer is the second most common cause of male cancer deaths in the United States. However, the full range of prostate cancer genomic alterations is incompletely characterized. Here we present the complete sequence of seven primary human prostate cancers and their paired normal counterparts. Several tumours contained complex chains of balanced (that is, ‘copy-neutral’) rearrangements that occurred within or adjacent to known cancer genes. Rearrangement breakpoints were enriched near open chromatin, androgen receptor and ERG DNA binding sites in the setting of the ETS gene fusion TMPRSS2–ERG, but inversely correlated with these regions in tumours lacking ETS fusions. This observation suggests a link between chromatin or transcriptional regulation and the genesis of genomic aberrations. Three tumours contained rearrangements that disrupted CADM2, and four harboured events disrupting either PTEN (unbalanced events), a prostate tumour suppressor, or MAGI2 (balanced events), a PTEN interacting protein not previously implicated in prostate tumorigenesis. Thus, genomic rearrangements may arise from transcriptional or chromatin aberrancies and engage prostate tumorigenic mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Among men in the United States, prostate cancer accounts for more than 200,000 new cancer cases and 32,000 deaths annually1. Although androgen deprivation therapy yields transient efficacy, most patients with metastatic prostate cancer eventually die of their disease. These aspects underscore the critical need to articulate both genetic underpinnings and novel therapeutic targets in prostate cancer.

Recent years have heralded a marked expansion in our understanding of the somatic genetic basis of prostate cancer. Of considerable importance has been the discovery of recurrent gene fusions that render ETS transcription factors under the control of androgen-responsive or other promoters2,3,4,5. These findings suggest that genomic rearrangements may comprise a major mechanism driving prostate carcinogenesis. Other types of somatic alterations also engage important mechanisms6,7,8; however, the full spectrum of prostate cancer genomic alterations remains incompletely characterized. Moreover, although the androgen signalling axis represents an important therapeutic focal point9,10, relatively few additional drug targets have yet been elaborated by genetic studies of prostate cancer11. To discover additional genomic alterations that may underpin lethal prostate cancer, we performed paired-end, massively parallel sequencing on tumour and matched normal genomic DNA obtained from seven patients with ‘high-risk’ primary prostate cancer.

Landscape of genomic alterations

All patients harboured tumours of stage T2c or greater, and Gleason grade 7 or higher. Serum prostate-specific antigen levels ranged from 2.1 to 10.2 ng ml−1 (Supplementary Table 1). Three tumours contained chromosomal rearrangements involving the TMPRSS2 (transmembrane protease, serine 2)–ERG (v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homologue (avian)) loci as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR)2 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). We obtained approximately 30-fold mean sequence coverage for each sample, and reliably detected somatic mutations in more than 80% of the genome (described in Supplementary Information). Circos plots12 indicating genomic rearrangements and copy number alterations for each prostate cancer genome are shown in Fig. 1.

Each Circos plot12 depicts the genomic location in the outer ring and chromosomal copy number in the inner ring (red, copy gain; blue, copy loss). Interchromosomal translocations and intrachromosomal rearrangements are shown in purple and green, respectively. Genomes are organized according to the presence (top row) or absence (bottom row) of the TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusion.

We identified a median of 3,866 putative somatic base mutations (range 3,192–5,865) per tumour (Supplementary Table 2); the estimated mean mutation frequency was 0.9 per megabase (see Supplementary Methods). This mutation rate is similar to that observed in acute myeloid leukaemia and breast cancer13,14,15,16 but 7–15-fold lower than rates reported for small cell lung cancer and melanoma17,18,19. The mutation rate at CpG (that is, cytosine–phosphate–guanine) dinucleotides was more than tenfold higher than at all other genomic positions (Supplementary Fig. 1). A median of 20 non-synonymous base mutations per sample were called within protein-coding genes (range 13–43; Supplementary Table 3). We also identified six high-confidence coding indels (4 deletions, 2 insertions) ranging from 1 to 9 base pairs (bp) in length, including a 2-bp frameshift insertion in the tumour suppressor gene, PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue; Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Two genes (SPTA1 and SPOP) harboured mutations in two out of seven tumours. SPTA1 encodes a scaffold protein involved in erythroid cell shape specification, while SPOP encodes a modulator of Daxx-mediated ubiquitination and transcriptional regulation20. The SPOP mutations exceeded the expected background rate in these tumours (Q = 0.055). (Q is defined as the false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected P value.) Moreover, SPOP was also found significantly mutated in a separate study of prostate cancer21. Interestingly, the chromatin modifiers CHD1, CHD5 and HDAC9 were mutated in 3 out of 7 prostate cancers. These genes regulate embryonic stem cell pluripotency, gene regulation, and tumour suppression22,23,24. Members of the HSP-1 stress response complex (HSPA2, HSPA5 and HSP90AB1) were also mutated in three out of seven tumours. The corresponding proteins form a chaperone complex targeted by several anticancer drugs in development25. Furthermore, we found a single KEGG pathway ‘antigen processing and presentation’ to be significantly mutated out of 616 diverse gene sets corresponding to gene families and known pathways (Q = 0.0021). This result is intriguing, given the clinical benefit associated with immunotherapy for prostate cancer26,27. Other known cancer genes were mutated in single tumours, including PRKCI and DICER. Thus, some coding mutations may contribute to prostate tumorigenesis and suggest possible therapeutic interventions.

Complex patterns of balanced rearrangements

Given the importance of oncogenic gene fusions in prostate cancer, we next characterized the spectrum of chromosomal rearrangements. We identified a median of 90 rearrangements per genome (range 43–213) supported by ≥3 distinct read pairs (Supplementary Table 5). This distribution of rearrangements was similar to that previously described for breast cancer28. We examined 594 candidate rearrangements by multiplexed PCR followed by massively parallel sequencing, and validated 78% of events by this approach (Supplementary Methods). Three genes disrupted by rearrangements also harboured non-synonymous mutations in another sample: ZNF407, CHD1 and PTEN. Notably, the chromatin modifier CHD1, which contains a validated splice site mutation in prostate tumour PR-1701 (as indicated above), also harboured intragenic breakpoints in two additional samples (PR-0508 and PR-1783). These rearrangements predict truncated proteins, raising the possibility that dysregulated CHD1 may contribute to a block in differentiation in some prostate cancer precursor cells22.

In 88% of cases, the fusion point could be mapped to base pair resolution (Supplementary Methods). The most common type of fusion involved a precise join, with neither overlapping nor intervening sequence at the rearrangement junction. In a minority of cases, an overlap (microhomology) of 2 bp or more was observed. The rearrangement frequency declined by approximately twofold for each base of microhomology. This result differed from the patterns seen in breast tumours, in which the most common junction involved a microhomology of 2–3 bp (ref. 28). Thus, mechanisms by which rearrangements are generated may differ between prostate and breast cancer.

Detailed examination of these chromosomal rearrangements revealed a distinctive pattern of balanced breaking and rejoining not previously observed in solid tumours: several genomes contained complex inter- and intra-chromosomal events involving an exchange of ‘breakpoint arms’. A mix of chimaeric chromosomes was thereby generated, without concomitant loss of genetic material (that is, all breakpoints produced balanced translocations, illustrated conceptually in Fig. 2a).

a, Diagram of ‘closed chain’ pattern of chromosomal breakage and rejoining. Breaks are induced in a set of loci (left), followed by an exchange of free ends without loss of chromosomal material (middle), leading to the observed pattern of balanced (copy neutral) translocations involving a closed set of breakpoints (right). b, Complex rearrangement in prostate tumour PR-1701. TMPRSS2–ERG is produced by a closed quartet of balanced rearrangements involving 4 loci on chromosomes 1 and 21. Top, each rearrangement is supported by the presence of discordant read pairs in the tumour genome but not the normal genome (coloured bars connected by blue lines). Thin bars represent sequence reads; directionality represents mapping orientation on the reference genome. Figures are based on the Integrative Genomics Viewer (http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv). Bottom, Diagram of breakpoints and balanced translocations. Hatching indicates sequences that are duplicated in the derived chromosomes at the resulting fusion junctions. c, Complex rearrangement in prostate tumour PR-2832 involving breakpoints and fusions at 9 distinct genomic loci. Hatching indicates sequences that are duplicated or deleted in the derived chromosomes at the resulting fusion junctions. For breakpoints in intergenic regions, the nearest gene in each direction is shown. In addition to the sheer number of regions involved, this complex rearrangement is notable for the abundance of breakpoints in or near cancer-related genes, such as TBK1, MAP2K4, TP53 and ABL1.

This ‘closed chain’ pattern of breakage and rejoining was evident in each of the TMPRSS2–ERG fusion-positive prostate cancers. In two such cases, both the TMPRSS2 and ERG genomic loci were involved in a closed chain of breakpoints. For example, the TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusion in PR-1701 was produced by a closed quartet of balanced translocations on chromosomes 21 and 1 (Fig. 2b). The TMRPSS2–ERG gene fusion in PR-0581 occurred within a closed trio of intrachromosomal rearrangements involving C21ORF45, ERG and TMPRSS2 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

One noteworthy closed chain of rearrangements harboured breakpoints situated independently of TMPRSS2–ERG (Supplementary Fig. 4) but in close proximity to multiple known cancer genes or orthologues. This chain (found in sample PR-2832) contained breakpoint pairs at the following loci: (1) 60 bp from exon 6 of TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1 or ‘NF-kB-activating kinase’)29; (2) within the first intron of TP53 (7 kilobases (kb) upstream of translation start); (3) 51 kb from MAP2K4 (a kinase recently shown to induce anchorage-independent growth via mutations21); and (4) 3 kb from the ABL1 proto-oncogene (Fig. 2c). This striking phenomenon suggests that complex translocations may dysregulate multiple genes in parallel to drive prostate tumorigenesis.

Association of rearrangements and epigenetic marks

The closed chain pattern of chromosomal breakpoints also raised the possibility that multiple genomic regions might become spatially co-localized before undergoing rearrangement. Conceivably, such a phenomenon could reflect migration to ‘transcription factories’—preassembled nuclear subcompartments that contain RNA polymerase II holoenzyme30. In prostate cells, androgen signalling has been shown to induce co-localization of TMPRSS2 and ERG, thereby allowing double-strand breaks to facilitate gene fusion formation31,32,33. A role for transcription in the genesis of TMPRSS2–ERG in PR-1701 seems plausible, as genomic sequences of up to 240 bp are duplicated at the resulting fusion junctions (Fig. 2b). Alternatively, chains of breakpoints might reflect the clustering of active and inactive chromatin within the recently demonstrated fractal globule structure of nuclear architecture34. Stimulated by these models, we considered whether the genomic regions involved in prostate cancer rearrangements exhibited similarities in terms of either transcriptional patterns or chromatin marks. Here, we used published chromatin immunoprecipitation and massively parallel sequencing (ChIP-seq) data from VCaP, an androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cell line that harbours the TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusion35.

The location of rearrangement breakpoints from the TMPRSS2–ERG fusion-positive tumour PR-2832 showed significant spatial correlation with various marks of open chromatin in VCaP cells (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). These marks included ChIP-seq peaks corresponding to RNA polymerase II (pol II, P = 1.0 × 10−15), histone H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3, P = 3.1 × 10−7), histone H3K36 trimethylation (H3K36me3, P = 3.5 × 10−12) and histone H3 acetylation (H3ace, P = 9.5 × 10−12) (Fig. 3). Similar statistical correlations were observed for peaks corresponding to the androgen receptor (AR) (P = 1.1 × 10−5) and ERG binding sites (P = 4.9 × 10−14) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 6), consistent with the substantial overlap between AR and ERG binding locations in VCaP cells35. (We did not observe significant enrichment of either AR or ERG binding site sequences in the vicinity of these breakpoints.) In the other ERG fusion-positive tumours (PR-0581 or PR-1701), the correlations between breakpoints and ChIP-seq peaks were intermittently apparent, albeit much less significant.

ChIP-seq binding peaks were defined previously for the TMPRSS2–ERG positive (ERG-positive) prostate cancer cell line VCaP35. For each genome, enrichment of breakpoints within 50 kb of each set of binding peaks was determined relative to a coverage-matched simulated background (see Methods). TMPRSS2–ERG-positive prostate tumours are in black; ETS fusion-negative prostate tumours are in white. Enrichment is displayed as the ratio of the observed breakpoint rate to the background rate near each indicated set of ChIP-seq peaks. Rearrangements in ETS fusion-negative tumours are depleted near marks of active transcription (AR, ERG, H3K4me3, H3K36me3, Pol II and H3ace) and enriched near marks of closed chromatin (H3K27me3). P-values were calculated according to the binomial distribution and are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 6. *Significant associations passing a false discovery rate cut-off of 5%.

Rearrangement breakpoints from all four ETS fusion-negative tumours were inversely correlated with these same marks of open chromatin and AR/ERG binding (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). In fact, breakpoints from two of four ETS-negative tumours were significantly correlated with marks of histone H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) in VCaP cells, which denote inactive chromatin and transcriptional repression (Fig. 3). This result suggested that somatic rearrangements might occur within closed chromatin in some tumour cells, or that the epigenetic architecture or transcriptional program of some TMPRSS2–ERG fusion-positive cells differs markedly from that of ERG fusion-negative cells. In support of the former, we observed a similar enrichment of PR-2832 rearrangements and depletion of fusion-negative rearrangements near marks of active transcription profiled in several additional cell lines, including fusion-negative prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and PC-3 as well as three cell lines derived from non-prostate lineages (Supplementary Fig. 5)35,36,37.

On the basis of these results, we performed similar analyses comparing the chromatin state in VCaP cells to rearrangement patterns of other cancer types. No statistically significant correlations or inverse correlations were observed between VCaP ChIP-seq data and rearrangement breakpoints obtained from a melanoma cell line18, a small-cell lung cancer cell line17, or a primary non-small-cell lung tumour38 (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 6). However, rearrangements from 16 out of 18 breast tumours and cell lines examined28 exhibited a pattern of association similar to that observed in prostate tumour PR-2832 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Notably, breakpoints in these tumours were also strongly associated with oestrogen receptor (ER) binding sites derived from the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 (ref. 39). Furthermore, we observed a strong association between ER ChIP-seq peaks from MCF-7 and all VCaP ChIP-seq peaks corresponding to open chromatin, AR and ERG binding (P < 10−90; Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus, patterns of open chromatin may be highly overlapping in some hormone-driven cancer cells. Such regions may correlate significantly with sites of somatic rearrangement in cancers of the prostate, breast, and possibly other tissues.

To examine whether processes linked to chromatin reorganization and DNA rearrangement are also associated with increased mutation frequency, we tested for enrichment of point mutations near regions of ChIP-seq peaks and rearrangement breakpoints. We observed a significantly reduced prevalence of point mutations near marks of VCaP active transcription—and slight enrichment of mutations in closed chromatin—in all seven prostate tumours (Supplementary Fig. 7). This pattern is consistent with both negative selection and transcription-coupled DNA repair. Additionally, we observed a significant enrichment of mutations near rearrangement breakpoints in five out of seven prostate tumours (Supplementary Fig. 7). Although the increased rate of mutations near rearrangements may conceivably reflect activation-induced cytodine deaminase in the double strand break repair process31,40, we did not observe a significant overrepresentation of any one class of mutation among those located near breakpoints.

Recurrent rearrangements involving CADM2

Sixteen genes harboured a somatic rearrangement in at least two prostate tumours (Supplementary Table 7), and four contained rearrangements in three out of seven tumours. In addition to TMPRSS2 and ERG, the latter included CSMD3 and CADM2 (cell adhesion molecule 2). These genes were rearranged at a frequency beyond that expected by chance, even after correcting for gene size (Supplementary Table 8). CSMD3 encodes a giant gene that contains multiple CUB and sushi repeats. However, we did not observe additional CSMD3 rearrangements by FISH in an independent analysis of 94 prostate tumours (Supplementary Fig. 8).

CADM2 encodes a nectin-like member of the immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecules. Several nectin-like proteins exhibit tumour suppressor properties in various contexts. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array-derived copy number profiles of tumours and cell lines41,42 suggests that CADM2 does not reside near a fragile site (Supplementary Fig. 9). At the same time, the complexity of CADM2 rearrangements (Fig. 4a) suggested that a simple FISH validation approach might prove insufficient to determine the overall frequency of CADM2 disruption. Nevertheless, we screened an independent cohort of 90 additional prostate tumours using a ‘break-apart’ FISH assay designed to query the CADM2 locus (Supplementary Fig. 8). CADM2 aberrations were detected in 6 out of 90 samples (5 rearrangements and 1 copy gain; Fig. 4b). These results confirmed that CADM2 is recurrently disrupted in prostate cancer, and they are likely to represent a lower bound for the true prevalence of CADM2 alteration in this malignancy.

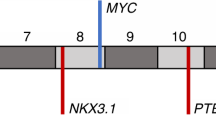

a, Location of intragenic breakpoints in CADM2. b, CADM2 break-apart demonstrated by FISH in an independent prostate tumour. c, Location of intragenic breakpoints in PTEN (top) and MAGI2 (bottom). d, MAGI2 inversion demonstrated by FISH in an independent prostate tumour, using probes flanking MAGI2 (red and green) and an external reference probe also on chromosome 7q (green). The probes and strategy for detecting novel rearrangements by FISH are shown in diagram form in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Rearrangements disrupting PTEN and MAGI2

Two prostate tumours contained breakpoints within the PTEN tumour suppressor gene6 (Fig. 4c). In both cases, the rearrangements generated heterozygous deletions that were confirmed by FISH analysis (Supplementary Fig. 10). In one tumour (PR-0581), PTEN rearrangement co-occurred with a dinucleotide insertion within the PTEN coding sequence (described above).

Two additional tumours harboured rearrangements disrupting the MAGI2 (membrane associated guanylate kinase, WW and PDZ domain containing 2) gene, which encodes a PTEN-interacting protein43,44 (Fig. 4c). In one tumour (PR-0508), two independent but closely aligned inversion events (marking both ends of a 450-kb inverted sequence) affected the MAGI2 locus. In the other tumour (PR-2832), two long-range intrachromosomal inversions were observed, raising the possibility of heterogeneous subclones harbouring independent MAGI2 rearrangements. Thus, four out of seven tumours harboured rearrangements predicted to inactivate PTEN or MAGI2, including all three tumours harbouring TMPRSS2–ERG rearrangements. Although a tumour suppressor function for MAGI2 has not been established previously, this gene was recently shown to undergo rearrangement in the genome of a melanoma cell line18, another tumour type in which PTEN loss is prevalent. In principle, genomic rearrangements that subvert PTEN function either directly or indirectly (for example, through loss of MAGI2) might dysregulate the PI3 kinase pathway in prostate cancer.

Whereas both PTEN rearrangements involved chromosomal copy loss, the MAGI2 rearrangements were balanced events (Supplementary Fig. 11). Like CSMD3 and CADM2, MAGI2 does not appear to reside near a fragile site (Supplementary Fig. 9). We screened 88 independent prostate tumours using FISH inversion probes and identified 3 additional samples harbouring similar inversions, each of which was wild type for PTEN disruption (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 8). As with CADM2 above, these FISH findings may underestimate the true frequency of MAGI2 disruption in prostate cancer.

We further analysed the PTEN and MAGI2 loci using high-density SNP arrays obtained from 66 primary prostate cancers. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, focal somatic deletions affecting the PTEN locus were commonly observed in these tumours, as expected. Interestingly, no somatic copy number alterations were observed at the MAGI2 locus in either prostate tumour found to contain MAGI2 rearrangements by genome sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 11). Conceivably, this region may also harbour genes whose loss would be deleterious to prostate cancer cells. More generally, these findings suggest that extensive shotgun paired-end sequencing (as opposed to lower-resolution approaches) may be required to elaborate the compendium of genes targeted by somatic alterations in prostate cancer.

Discussion

This study represents the first whole genome sequencing analysis of human prostate cancer. Systematic genome characterization efforts have often focused primarily on gene-coding regions to identify ‘driver’ or ‘druggable’ alterations45,46,47. In contrast, the high prevalence of recurrent gene fusions has highlighted chromosomal rearrangements as critical initiating events in prostate cancer2,3. Genome sequencing data indicate that complex rearrangements may enact pivotal gain- and loss-of-function driver events in primary prostate carcinogenesis. Moreover, many rearrangements may occur preferentially in genes that are spatially localized together with transcriptional or chromatin compartments, perhaps initiated by DNA strand breaks and erroneous repair. The complexity of ‘closed chain’ and other rearrangements suggests that complete genome sequencing—as opposed to approaches focused on exons or gene fusions—may be required to elaborate the spectrum of mechanisms directing prostate cancer genesis and progression.

A positive correlation exists between the location of breakpoints in TMPRSS2–ERG-positive tumour cells and open chromatin in VCaP cells, and also between breakpoints present in ETS fusion-negative cells and VCaP regions of closed chromatin. This suggests that breakpoints may preferentially occur within regions of open chromatin in some TMPRSS2–ERG-positive tumour cells while raising alternative possibilities for the genesis of breakpoints in ETS fusion-negative cells. Conceivably, somatic rearrangements may occur within regions of closed chromatin in tumour cells lacking ETS gene fusions. Alternately, such tumour cells may have distinct transcriptional or chromatin patterns, with many regions that are closed in VCaP being open in these cells. Clustering of breakpoints within active regions might also reflect selection for functionally consequential rearrangements during tumorigenesis. The relative contribution of these aspects to tumorigenesis will probably be informed by additional integrative analyses of epigenetic and structural genomic data sets across many tumour types.

Previous studies of genetically engineered mouse models have shown that the combination of ERG dysregulation and PTEN loss triggers the formation of aggressive prostate tumours48,49. This same combination identifies a subtype of human prostate cancer characterized by poor prognosis50. The discovery of MAGI2 genomic rearrangements in prostate cancer suggests that interrogating both the PTEN and MAGI2 loci might improve prognostication and patient stratification for clinical trials of PI3 kinase pathway inhibitors. Additional mutated genes discovered in this study also suggest interesting therapeutic avenues. For example, the presence of point mutations involving chromatin modifying genes and the HSP-1 stress response complex (which includes the Hsp90 chaperone protein targeted by several drugs in development) raises the possibility that these cellular processes may represent targetable dependencies in some prostate tumours. Overall, complete genome sequencing of large numbers of relapsing primary and metastatic prostate cancers promises to define a genetic cartography that assists in tumour classification, elaborates mechanisms of carcinogenesis and identifies new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Methods Summary

The complete genomes of seven prostate tumours and patient-matched normal samples were sequenced to approximately 30-fold haploid coverage on an Illumina GA II sequencer. DNA was extracted from patient blood and from tumours following radical prostatectomy, and was subjected to extensive quality control procedures to monitor DNA structural integrity, genotype concordance, and tumour purity and ploidy. Standard paired-end libraries (∼400-bp inserts) were sequenced as 101-bp paired-end reads. Raw sequencing data were processed by Illumina software and passed to the Picard pipeline, which produced a single BAM file for each sample storing all reads with well-calibrated quality scores together with their alignments to the reference genome. BAM files for each tumour/normal sample pair were analysed by the Firehose pipeline to characterize the full spectrum of somatic mutations in each tumour, including base pair substitutions, short insertions and deletions, and large-scale structural rearrangements. A subset of base pair mutations and rearrangements were validated using independent technologies in order to assess the specificity of the detection algorithms. FISH was also performed for selected recurrent rearrangements. The locations of all rearrangement breakpoints were compared to previously published ChIP binding peaks from related cell types to test for global associations between rearrangements and a range of epigenetic marks. A complete description of the materials and methods is provided in Supplementary Information.

Accession codes

Data deposits

All Illumina sequence data have been deposited in dbGaP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap) and are available at accession phs000330.v1.p1.

References

Jemal, A., Siegel, R., Xu, J. & Ward, E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 60, 277–300 (2010)

Tomlins, S. A. et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science 310, 644–648 (2005)

Tomlins, S. A. et al. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature 448, 595–599 (2007)

Helgeson, B. E. et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2:ETV5 and SLC45A3:ETV5 gene fusions in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 73–80 (2008)

Tomlins, S. A. et al. TMPRSS2:ETV4 gene fusions define a third molecular subtype of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 3396–3400 (2006)

Li, J. et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science 275, 1943–1947 (1997)

Visakorpi, T. et al. In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nature Genet. 9, 401–406 (1995)

Taylor, B. S. et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 18, 11–22 (2010)

Tran, C. et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science 324, 787–790 (2009)

Attard, G. et al. Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 4563–4571 (2008)

Palanisamy, N. et al. Rearrangements of the RAF kinase pathway in prostate cancer, gastric cancer and melanoma. Nature Med. 16, 793–798 (2010)

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645 (2009)

Ley, T. J. et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature 456, 66–72 (2008)

Shah, S. P. et al. Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution. Nature 461, 809–813 (2009)

Mardis, E. R. et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1058–1066 (2009)

Ding, L. et al. Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature 464, 999–1005 (2010)

Pleasance, E. D. et al. A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure. Nature 463, 184–190 (2010)

Pleasance, E. D. et al. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature 463, 191–196 (2010)

Berger, M. F. et al. Integrative analysis of the melanoma transcriptome. Genome Res. 20, 413–427 (2010)

Kwon, J. E. et al. BTB domain-containing speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) serves as an adaptor of Daxx for ubiquitination by Cul3-based ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12664–12672 (2006)

Kan, Z. et al. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature 466, 869–873 (2010)

Gaspar-Maia, A. et al. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 460, 863–868 (2009)

Zhang, C. L., McKinsey, T. A. & Olson, E. N. Association of class II histone deacetylases with heterochromatin protein 1: potential role for histone methylation in control of muscle differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7302–7312 (2002)

Bagchi, A. et al. CHD5 is a tumor suppressor at human 1p36. Cell 128, 459–475 (2007)

Pearl, L. H., Prodromou, C. & Workman, P. The Hsp90 molecular chaperone: an open and shut case for treatment. Biochem. J. 410, 439–453 (2008)

Kantoff, P. W. et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 411–422 (2010)

Kantoff, P. W. et al. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 1099–1105 (2010)

Stephens, P. J. et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature 462, 1005–1010 (2009)

Barbie, D. A. et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature 462, 108–112 (2009)

Osborne, C. S. et al. Active genes dynamically colocalize to shared sites of ongoing transcription. Nature Genet. 36, 1065–1071 (2004)

Lin, C. et al. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell 139, 1069–1083 (2009)

Mani, R. S. et al. Induced chromosomal proximity and gene fusions in prostate cancer. Science 326, 1230 (2009)

Haffner, M. C. et al. Androgen-induced TOP2B-mediated double-strand breaks and prostate cancer gene rearrangements. Nature Genet. 42, 668–675 (2010)

Lieberman-Aiden, E. et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293 (2009)

Yu, J. et al. An integrated network of androgen receptor, polycomb, and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 17, 443–454 (2010)

Lin, B. et al. Integrated expression profiling and ChIP-seq analyses of the growth inhibition response program of the androgen receptor. PLoS ONE 4, e6589 (2009)

Birney, E. et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 (2007)

Lee, W. et al. The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature 465, 473–477 (2010)

Krum, S. A. et al. Unique ERα cistromes control cell type-specific gene regulation. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 2393–2406 (2008)

Yang, Y., Sterling, J., Storici, F., Resnick, M. A. & Gordenin, D. A. Hypermutability of damaged single-strand DNA formed at double-strand breaks and uncapped telomeres in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . PLoS Genet. 4, e1000264 (2008)

Beroukhim, R. et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 463, 899–905 (2010)

Bignell, G. R. et al. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature 463, 893–898 (2010)

Wu, X. et al. Evidence for regulation of the PTEN tumor suppressor by a membrane-localized multi-PDZ domain containing scaffold protein MAGI-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4233–4238 (2000)

Vazquez, F. et al. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail acts as an inhibitory switch by preventing its recruitment into a protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48627–48630 (2001)

Sjoblom, T. et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 314, 268–274 (2006)

Parsons, D. W. et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science 321, 1807–1812 (2008)

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455, 1061–1068 (2008)

Carver, B. S. et al. Aberrant ERG expression cooperates with loss of PTEN to promote cancer progression in the prostate. Nature Genet. 41, 619–624 (2009)

King, J. C. et al. Cooperativity of TMPRSS2-ERG with PI3-kinase pathway activation in prostate oncogenesis. Nature Genet. 41, 524–526 (2009)

Han, B. et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization study shows association of PTEN deletion with ERG rearrangement during prostate cancer progression. Mod. Pathol. 22, 1083–1093 (2009)

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Leung and all members of the Broad Institute Sequencing Platform. This work was supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation/Movember (T.R.G., M.A.R., L.A.G.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (T.R.G.), the National Human Genome Research Institute (S.B.G., E.S.L.), the Kohlberg Foundation (P.W.K., L.A.G.), the National Cancer Institute (NCI; F.D., M.A.R., M.M.), the NCI Early Detection Research Network (M.A.R.), the National Institutes of Health (L.A.G.), the Department of Defense (F.D.), the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Prostate Cancer SPORE grant 2 P50 CA090381-11 (P.W.K.), and the Starr Cancer Consortium (M.F.B., F.D., M.A.R., L.A.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S.L., G.G., M.A.R. and L.A.G. contributed equally to this work. M.F.B, E.S.L., G.G., M.A.R., and L.A.G. designed the study, analysed the data, and wrote the paper. M.S.L., F.D., and Y.D. performed analysis of mutations, copy number, rearrangements and ChIP-seq associations. K.C. and A.Y.S. performed analysis of mutations and indels. R.E., D.P., N.K., A.T. and M.A.R. contributed to the procurement of tumour tissue and preparation of DNA. C.S, R.O., W.W., S.M. and K.A. participated in DNA sample processing, quality control, and SNP microarray experiments. L.A., J.W., S.F., J.B. and S.B.G. generated the DNA sequence data. A.S., S.L.C., L.H., T.F., G.S., D.V., A.H.R. and T.J.P. provided additional bioinformatic analyses. K.P., T.Y.M. and M.A.R. performed FISH experiments. M.F.B, M.S.L., R.O., M.P., W.W., G.G. and L.A.G. validated candidate rearrangements. J.W.S., P.W.K., L.C., S.B.G., M.B.G., T.R.G. and M.M. contributed to the study design and interpretation of data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

The file contains Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figures 1-12 with legends and additional references. (PDF 8936 kb)

Supplementary Tables

The file contains Supplementary Tables 1-9. (XLSX 1707 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This licence does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar licence.

About this article

Cite this article

Berger, M., Lawrence, M., Demichelis, F. et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature 470, 214–220 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09744

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09744

This article is cited by

-

Establishment of primary prostate epithelial and tumorigenic cell lines using a non-viral immortalization approach

Biological Research (2024)

-

Photothermal therapy of papillary thyroid cancer tumor xenografts with targeted thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes

Cancer Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Pan-cancer genomic analysis shows hemizygous PTEN loss tumors are associated with immune evasion and poor outcome

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The testosterone paradox of advanced prostate cancer: mechanistic insights and clinical implications

Nature Reviews Urology (2023)

-

Clinical significance of SPOP and APC gene alterations in colorectal cancer in Indian population

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.