Abstract

Morphologic distinction of high-grade adenoid cystic carcinoma from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma can be difficult. Equivocal diagnoses can mislead treatment. We have investigated the possibility that immunohistochemical staining for the presence of p63, a novel epithelial stem-cell regulatory protein, could be a useful means of distinguishing these two neoplasms. Archival, routinely processed slides were subjected to citrate-based antigen retrieval, exposure to anti-p63 monoclonal 4A4, and developed with a streptavidin–biotin kit and diaminobenzidine as chromogen. p63 was detected in 100% of the adenoid cystic carcinomas (n=14) and 100% of basaloid squamous cell carcinomas (n=16). Basaloid squamous cell carcinomas consistently displayed diffuse p63 positivity, with staining of nearly 100% of tumor cells. In contrast, adenoid cystic carcinoma displayed a consistently compartmentalized pattern within tumor nests. Compartmentalization was manifested in two patterns: (1) selective staining of a single peripheral layer of p63-positive cells surrounding centrally located tumor cells that were p63-negative and (2) tumor nests consisting of multiple contiguous glandular/cribriform-like units of p63-positive cells surrounding or interspersed with p63-negative cells. p63 immunostaining constitutes a specific and accurate means of distinguishing adenoid cystic carcinoma from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. p63 positivity in adenoid cystic carcinoma appears to be homologous to that seen in the basal and/or myoepithelial compartments of salivary gland and other epithelia, and may signify a stem-cell-like role for these peripheral cells. Diffuse p63 positivity in basaloid squamous cell carcinoma suggests dysregulation of p63-positive stem cells in poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

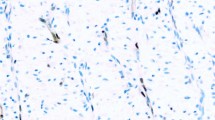

The distinction of adenoid cystic carcinoma from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma can be difficult or impossible. Basaloid squamous cell carcinomas may have areas of obvious squamous differentiation admixed with solid tumor islands that exhibit peripheral palisading and a thick basement membrane. However, particularly in small biopsies, obvious squamous differentiation and palisading may not be identified and it is not uncommon for moderately to poorly differentiated basaloid squamous cell carcinomas to undergo central cystification with accumulation of hyaline granules and to appear very similar to adenoid cystic carcinoma on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Conversely, adenoid cystic carcinomas composed of solid arrays of tumor cells may be difficult to distinguish from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma.1 The optimal treatment regimen is different for each entity. Treatment of adenoid cystic carcinoma involves surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. There is no effective chemotherapeutic agent. Basaloid squamous cells carcinoma is treated with surgery, radiotherapy, or both, with or without chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil and cisplatin).2, 3, 4

p63 was discovered in a screen for p53-homologous genes. Like p53, p63 codes for proteins with an amino(N)-terminal transcription-activating region, a middle DNA-binding region, and a carboxyl terminal region responsible for oligomerization.5 p63 comprises at least six different protein isoforms with homology to the tumor suppressor protein p53. They are generated from a single gene by two promoters and alternative splicing of the primary RNA transcript.5 Certain isoforms (TAp63) are able to transactivate p53 target genes. Other isoforms (ΔNp63) act as dominant-negative factors that inhibit transcription activation by both p53 and TAp63 isoforms.5 The ΔNp63α isoform appears to be a master regulator of squamous stem-cell differentiation.6 Transgenic mice lacking p63 are born without skin, mammary, lachrymal and salivary gland tissue, reflecting a critical role in the development and/or maintenance of several types of epithelia.7, 8

Previous studies in several laboratories have shown p63 expression in many normal tissues including squamous epithelia, urothelium, bronchial epithelium, and the myoepithelial layers of breast, prostate and submucosal glands.9, 10, 11, 12 Expression has also been established in a variety of neoplasms, including squamous, urothelial, endometrial, and papillary thyroid carcinomas and thymomas.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

p63 expression in salivary gland and salivary neoplasms has also been investigated. Benign myoepithelial cells of salivary gland, like those of normal breast and prostate epithelium, express p63.21 Di Como et al9 reported p63 expression in four pleomorphic adenomas and two of four carcinomas of the salivary glands. Bilal et al found that for all salivary gland-derived tumor types that differentiated towards luminal and myoepithelial lineages (pleomorphic adenomas, basal cell adenomas, and adenoid cystic carcinomas), p63 was expressed in myoepithelial cells, whereas internal luminal cells were always negative. In 11 out of 11 adenoid cystic carcinomas, they found the peripheral cells of myoepithelial differentiation to be diffusely and strongly reactive for p63 while all luminal cells were p63-nonreactive.22

We investigated the possibility that p63 immunostaining could be of value in resolving the often difficult differential diagnosis of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma vs adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Materials and methods

In total, 14 archival head and neck adenoid cystic carcinomas and 16 basaloid squamous cell carcinomas were examined. The adenoid cystic carcinomas were from parotid (n=4), sublingual gland (n=3), nasopharynx (n=1), maxillary sinus (n=1), maxilla (n=1), submandibular gland (n=1), mandible (n=1), larynx (n=1) and hard palate (n=1). The basaloid squamous cell carcinomas arose in the tonsil (n=7), tongue (n=4), sinonasal area (n=2), larynx (n=2) and pharynx (n=1). Two of the adenoid cystic carcinomas and three of the basaloid squamous cell carcinomas were small biopsies and the remainder were excision specimens.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed as follows: 4 μm thick sections were deparaffinized, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity, then treated with 0.01 M citric acid (pH 6.0) for 5 min at 100°C for antigen retrieval. Slides were then incubated overnight at room temperature with anti-p63 monoclonal antibody 4A4 (1:600 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), stained using a streptavidin–biotin kit (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA, catalog no. QP900-9L) and diaminobenzidine as a chromagen, then counterstained with hematoxylin. p63 expression was considered positive only if distinct nuclear staining was present.

Results

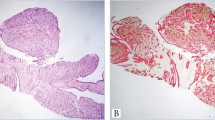

p63 was detected in all 14 adenoid cystic carcinomas and 16 basaloid squamous cell carcinomas. In the series of 16 basaloid squamous cell carcinomas, diffuse p63 staining of between 90 and 100% of tumor cells was consistently found. Some large tumor cell nests of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma contained central necrotic areas. p63 staining was characteristically strong, and occasionally of variable intensity (Figures 2 and 3). Only in a rare perinecrotic focus in an otherwise diffusely p63-positive basaloid squamous cell carcinoma, were isolated p63-negative tumor cells detected (Figure 4).

In the series of 14 adenoid cystic carcinomas, the p63 staining pattern was compartmentalized and readily distinguishable from the diffuse staining pattern present in basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Two patterns were noted:

-

1)

a purely peripheral pattern, noted in seven out of 14 cases, consisting of histomorphologically solid or cribriform nests in which p63-positive cells were exclusively located in a single layer at the periphery of the tumor cell nest and all but the peripheral layer of cells were p63-negative (Figures 5 and 6). When situated at the periphery of nests, the p63-positive cells were either scattered or extensively positive (Figures 5 and 6);

Figure 5 -

2)

a peripheral/internalized staining pattern, seen in five out of 14 cases, in which p63-positive cells were found internally in tumor nests as well as at the periphery. p63 staining appeared to identify glandular/cribriform-like units of p63-positive cells surrounding or interspersed with small groups of p63-negative cells, which in aggregate comprised larger tumor nests (Figures 7 and 8). In several such cases, the p63-positive cells at either the periphery or scattered within the nests were predominantly smaller in size than the p63-negative cells and unlike the p63-negative cells, appeared to lack nucleoli (Figure 8).

Figure 7 Figure 8 Adenoid cystic carcinoma with compartmentalized p63 staining. The p63-positive cells are predominantly smaller than the p63-negative cells, and appear to lack nucleoli (high power view of Figure 7 × 200).

In two of 14 cases, some nests showed the pure peripheral pattern, and other nests the peripheral/internalized pattern.

The case of adenoid cystic carcinoma with the highest proportion of p63-positive cells was a high-grade case consisting histomorphologically of cells with cribriform patterns in large sheets with comedo-like central necrosis. It consisted of p63-positive cells in the peripheral cell lining and many p63-positive cells (one-third to half of all tumor cells) internally in the cribriform regions (Figures 7 and 8).

The only circumstance in which a p63 staining pattern in adenoid cystic carcinoma in any way resembled the diffuse pattern of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma occurred in rare small solid nests that contained mostly p63-positive cells and rare p63-negative cells. However, in such cases, surrounding tumor nests displaying the characteristic compartmentalized staining predominated, allowing for ready distinction from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 9).

Discussion

We describe a means, via p63 immunostaining, of accurately distinguishing adenoid cystic carcinoma from basaloid squamous carcinoma. We found the p63 staining pattern of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma to differ strikingly from the staining pattern in adenoid cystic carcinoma. In the former, diffuse p63 staining of up to 100% of tumor cells was consistently found, whereas in adenoid cystic carcinoma, staining was compartmentalized.

The existence of a subpopulation of p63-positive cells in tumor cell nests in adenoid cystic carcinoma suggests the possibility that p63-positive cells may comprise a stem-cell compartment that drives the growth of this neoplasm. These p63-positive cells may both proliferate into other p63-positive stem cells, as well as differentiate into the centrally located or contiguous p63-negative tumor cells, much as basaloid p63-positive stem cells in normal squamous epithelia are thought to divide into two daughter cells, one retaining the p63-positive undifferentiated stem-cell-like phenotype, and one that differentiates into a p63-negative, nondividing mature squamous cell. This model would pinpoint the p63-positive cells in adenoid cystic carcinoma as the appropriate target cells for anti-adenoid cystic carcinoma therapeutic strategies.

In an alternative model, in adenoid cystic carcinomas manifesting the purely peripheral staining pattern, the peripheral layer of p63-positive cells may be the residual benign myoepithelial lining of normal ducts into which p63-negative cells extend intraductally by mass action rather than true invasion. This latter model would clearly not satisfactorily explain cases of adenoid cystic carcinoma with a peripheral/internalized pattern, with cribriform-like staining, in which p63-positive cells are also found internally within tumor nests.

To our knowledge, this peripheral/internal pattern of adenoid cystic carcinoma has not been previously described. Bilal et al22 reported that all adenoid cystic carcinomas studied showed selective staining of the peripheral cell layer; staining of internally located cells was not reported. It may be of future interest to compare the aggressiveness of adenoid cystic carcinomas displaying the purely peripheral pattern to those with the peripheral/internal pattern of p63 positivity.

In contrast to adenoid cystic carcinoma, the diffuse pattern of p63 positivity in basaloid squamous carcinomas may represent a complete failure of the normal program of squamous differentiation: a malignantly transformed basaloid stem cell, upon division and driven by unknown oncogenic mechanisms, yields two daughter cells, both of which stay undifferentiated, dividing, and p63-positive.

It appears that p63 expression may be a feature of neoplastic and non-neoplastic cell lineages that are squamous or are capable of undergoing squamous differentiation, including squamous-cell carcinomas of all sites, urothelial, endometrial, papillary thyroid carcinomas and thymomas.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Conversely, renal and Barrett's metaplastic epithelium and associated adenocarcinomas, which lack the capacity for squamous differentiation, are consistently p63-negative.16, 23 Adenoid cystic carcinomas, which lack the capacity for squamous differentiation but are p63-positive, appear to be one exception to this principle.

p63 positivity in adenoid cystic carcinoma presumably represents a neoplastic recapitulation of the p63-positive basal/myoepithelial cell phenotype present in normal salivary gland.

However, the pattern of p63 expression in adenoid cystic carcinoma differs from staining in adenocarcinomas derived from other types of acinar/glandular tissues with p63-positive myoepithelial cells. For example, normal breast and prostate, like salivary gland, have p63-positive basal or myoepithelial cells, yet most adenocarcinomas of the breast or prostate do not express p63.24, 25

While both adenoid cystic carcinoma and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma staining patterns suggest models that implicate tumor stem-cell function and dysfunction and raise interesting additional long-term questions impacting pathogenesis, therapy and prognosis that merit future investigation, the present findings suggest an immediate clinical benefit, via p63 immunostaining, in resolving the differential diagnosis between basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma.

References

Rosai J . Surgical Pathology, 9th edn. Mosby: New York, 2004, pp 258–259, 631.

Armstrong JG, Harrison LB, Spiro RH, et al. Malignant tumors of major salivary gland origin. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;116:290–293.

Sadeghi A, Tran LM, Mark R, et al. Minor salivary tumors of the head and neck: treatment strategies and prognosis. Am J Clin Oncol 1993;16:3–8.

Koide N, Kishimoto K, Nakamura T, et al. Basaloid-squamous carcinoma of the esophagus treated by preoperative chemotherapy: report of two cases. Surg Today 2003;33:444–447.

Yang A, Kaghad M, Caput D, et al. On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet 2002;18:90–95.

King KE, Ponnamperuma RM, Yamashita T, et al. DeltaNp63alpha functions as both a positive and a negative transcriptional regulator and blocks in vitro differentiation of murine keratinocytes. Oncogene 2003;22:3635–3644.

Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, et al. P63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 1999;398:714–718.

Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, et al. P63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 1999;398:708–713.

Di Como CJ, Urist MJ, Babayan I, et al. P63 expression profiles in human normal and tumor tissues. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:494–501.

Signoretti S, Waltregny D, Dilks J, et al. P63 is a prostate basal cell marker and is required for prostate development. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;157:1769–1775.

Barbareschi M, Pecciarini L, Cangi MG, et al. p63, a p53 homologue, is a selective nuclear marker of myoepithelial cells of the human breast. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1054–1060.

Wang BY, Gil J, Burstein DE, et al. p63 in pulmonary epithelium, pulmonary squamous neoplasms and other pulmonary tumors. Hum Pathol 2002;33:921–926.

Nylander K, Coates PJ, Hall PA . Characterization of the expression pattern of p63 alpha and delta Np63alpha in benign and malignant oral epithelial lesions. Int J Cancer 2000;87:368–372.

Quade BJ, Yang A, Wang Y, et al. Expression of the p53 homologue p63 in early cervical neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 2001;80:24–29.

Wang TY, Chen BF, Yang YC, et al. Histologic and immunophenotypic classification of cervical carcinomas by expression of the p53 homologue p63: a study of 250 cases. Hum Pathol 2001;32:479–486.

Glickman JN, Yang A, Shahsafaei A, et al. Expression of p53-related protein p63 in the gastrointestinal tract and in esophageal metaplastic and neoplastic disorders. Hum Pathol 2001;32:1157–1165.

Park BJ, Lee SJ, Kim JI, et al. Frequent alteration of p63 expression in human primary bladder carcinomas. Cancer Res 2000;60:3370–3374.

O'Connell JT, Mutter GL, Cviko A, et al. Identification of a basal/reserve cell immunophenotype in benign and neoplastic endometrium: a study with the p53 homologue p63. Gynecol Oncol 2001;80:30–36.

Unger P, Ewart M, Wang BY, et al. Expression of p63 in papillary thyroid carcinoma and in Hashimoto's thyroiditis: a pathobiologic link? Hum Pathol 2003; 34:764–769.

Chilosi M, Zamo A, Brighenti A, et al. Constitutive expression of DeltaN-p63alpha isoform in human thymus and thymic epithelial tumours. Virchows Arch 2003;443:175–183.

Weber A, Langhanki L, Schutz A, et al. Expression profiles of p53, p63, and p73 in benign salivary gland tumors. Virchows Arch 2002;441:428–436.

Bilal H, Handra-Luca A, Bertrand JC, et al. P63 is expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of human normal and tumor salivary gland tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 2003;51:133–139.

Black CC, Unger PD, Burstein DE, et al. Expression of p63 protein in subtypes of transitional cell and renal cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2002; 14:102A.

Stefanou D, Batistatou A, Nonni A, et al. P63 expression in benign and malignant breast lesions. Histol Histopathol 2004;19:465–471.

Shah RB, Zhou M, LeBlanc M, et al. Comparison of the basal cell-specific markers, 34betaE12 and p63, in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1161–1168.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Emanuel, P., Wang, B., Wu, M. et al. p63 Immunohistochemistry in the distinction of adenoid cystic carcinoma from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 18, 645–650 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800329

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800329

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Basaloid Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cervix: A Case Report

Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology (2024)

-

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with basaloid features are genetically and prognostically similar to conventional squamous cell carcinoma

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

Primary Intraosseous Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma with Widespread Skeletal Metastases Showing Features of High-Grade Transformation

Head and Neck Pathology (2021)

-

SOX10 Immunoexpression in Basaloid Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A Diagnostic Pitfall for Ruling out Salivary Differentiation

Head and Neck Pathology (2019)

-

Challenges in Minor Salivary Gland Biopsies: A Practical Approach to Problematic Histologic Patterns

Head and Neck Pathology (2019)