Abstract

The diagnosis of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate is one of the more difficult challenges in surgical pathology. This paper highlights the methodological approach to diagnosing limited cancer, based on a constellation of features more commonly present in adenocarcinoma than benign glands. In assessing small foci of atypical glands on needle biopsy, one looks for differences between the benign glands and the atypical glands in terms of nuclear features, cytoplasmic features, and intraluminal contents. Only a few features, such as glomerulations, mucinous fibroplasia (collagenous micronodules), and perineural invasion are diagnostic in and of themselves for prostate cancer. Immunohistochemistry may be a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate, although as with any immunohistochemical studies, there are problems with both sensitivity and specificity. Basal cell markers, such as high molecular weight cytokeratin and more recently, p63, highlight basal cells found in benign glands, yet are absent in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. However, not all benign glands label uniformly with basal cell markers. Certain mimickers of adenocarcinoma of the prostate are even less frequently labeled uniformly with these stains. Consequently, negative staining in a small focus of atypical glands for basal cell markers is not diagnostic of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. More recently, a marker has been identified that relatively selectively labels adenocarcinoma of the prostate. AMACR will label the cytoplasm of approximately 80% of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate cases on needle biopsy. In positive cases, not all of the glands will be positive and those that are positive are often not intensely positive. Certain variants of adenocarcinoma of the prostate that are a little more difficult to recognize, such as foamy glands adenocarcinoma, pseudohyperplastic adenocarcinoma, and atrophic adenocarcinoma, are labeled with AMACR in only approximately 60–70% of cases. In addition to problems with sensitivity, AMACR is not entirely specific for adenocarcinoma, and will label almost all cases of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, some foci of adenosis, and even some entirely benign glands. Finally, this paper will briefly cover the significance of atypical or suspicious prostate needle biopsies, and how to report the key diagnostic and prognostic information on needle biopsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Diagnosis of limited prostate cancer: routine hematoxylin-and-eosin stained sections

The underdiagnosis of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy is one of the most frequent problems in prostate pathology.1 It is hard to obtain data on this phenomenon, as most institutions do not want, for medicolegal reasons, to go back and review old cases for potential missed cases of cancer.

At the edge of most adenocarcinomas, scattered neoplastic glands infiltrate widely between larger benign glands. It is therefore not uncommon to have several needle biopsy cores of prostatic tissue where there are only a few malignant glands. The importance of recognizing limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate is that there is often no correlation between the amount of cancer seen on the needle biopsy and the amount of tumor present within the prostate. There may be only a few neoplastic glands in the core biopsy, despite significant tumor within the prostate gland.

It is important when examining needle biopsy specimens to gain an appreciation of what the non-neoplastic prostate looks like. In order to identify limited amounts of cancer on needle biopsy material, one first has to identify the normal non-neoplastic prostate and then look for glands that do not fit in. Although most prostates are relatively similar in their histological appearance, some contain numerous small foci of crowded glands similar to adenosis. In such a case, the diagnosis of cancer based on a small focus of crowded glands with minimal cytologic atypia should be performed with caution. Other men's prostate glands are characterized by widespread atrophy; one should in these cases hesitate to diagnose cancer if the atypical glands have scant cytoplasm.

Evaluating an atypical focus in a needle biopsy of the prostate should be a methodical process. When reviewing needle biopsies, one should develop a mental balance sheet where on one side of the column are features favoring the diagnosis of carcinoma and on the other side of the column features against the diagnosis of cancer (Table 1). At the end of evaluating a case, hopefully all of the criteria are listed on one side of the column or the other such that a definitive diagnosis can be made. The diagnosis of cancer should be based on a constellation of features rather than relying on any one criterion by itself.

The recognition of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate is first performed at low magnification. One pattern seen at low magnification that should raise a suspicion of carcinoma is the presence of a focus of crowded glands. The second architectural pattern that is suspicious for adenocarcinoma of the prostate is the presence of small glands situated between larger benign glands (Figures 1 and 2). In most adenocarcinomas, the neoplastic glands are smaller than adjacent benign glands. Benign glands are recognized by their larger size, papillary infolding, and branching. The presence of small cancerous glands situated in between benign glands is a manifestation of their infiltrative nature. When small atypical glands are seen on both sides of a benign gland, it is even more diagnostic of malignancy.

It is always helpful to first identify glands that you are confident are benign, and then compare these benign glands to the atypical glands which you are considering to diagnose as adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The greater the number of differences between the recognizable benign glands, and the atypical glands the more confidently a malignant diagnosis can be established.

Prominent nucleoli, while important in the diagnosis of cancer on needle biopsy, should not be the sole criterion used to establish the diagnosis (Figure 2). Reliance on prominent nucleoli for the diagnosis of prostate cancer will potentially lead both to an underdiagnosis as well as to an overdiagnosis of prostate cancer. The significance of prominent nucleoli must be taken in the context of the architectural pattern and other features present within the case. Although it has been stated that multiple nucleoli, especially those eccentrically located in the nucleus, are diagnostic of cancer, we have not utilized this criterion in our own practice; additional studies have not been performed to validate this criterion.2 Often, nuclear enlargement may be present when prominent nucleoli are not (Figure 3). Nuclear hyperchromatism is another cytologic feature that may help to distinguish cancerous from benign glands. Mitoses, although not frequent in adenocarcinoma of the prostate, are much more commonly seen in cancer than in benign glands (Figure 4).

Although in the past, there has been much less consideration paid to cytoplasmic features as compared to nuclear qualities, the nature of the cytoplasm may be critical in the diagnosis of some carcinomas. In some adenocarcinomas of the prostate, the cytoplasm of the malignant glands is more amphophilic than the surrounding benign glands that have pale to clear cytoplasm (Figure 5). In order for this criterion to be helpful, the benign prostate glands must be appropriately stained such that they have a pale to clear appearance. In a study of consult cases, we found that in 32% of the cases this criterion was not applicable since the benign glands also exhibited amphophilic cytoplasm.3 As we find this feature to be helpful in a large number of cases, one's hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains should be adjusted so that the cytoplasm of the benign glands appears pale to clear.

Another diagnostic criterion is the nature of intraluminal secretions (Figure 6). Blue-tinged mucinous secretions seen on H&E-stained sections are mostly observed in carcinomas, and only rarely identified in benign glands. The prevalence of these blue-tinged secretions is in part influenced by the nature of the H&E stain. In some institutions’ referral material, this feature appears to be fairly prevalent, whereas in other institutions, it is uncommonly seen. Some laboratory's H&E stains are too basophilic, where even benign glands contain blue-tinged mucinous secretions. When normal colonic glands that are present on most prostate biopsies show an intense blue appearance, pathologists have to be cautious in placing too much weight on blue-tinged mucin in prostate glands as a diagnostic criterion for cancer. Although initial reports suggested that acid mucin stains could distinguish malignant from benign glands, subsequent papers demonstrated that acid mucin is variably present in mimickers of carcinoma such as adenosis and atrophic glands.4, 5 Whereas corpora amylacea are prominent in benign glands and rarely seen in cancer, pink amorphous acellular secretions are identified in approximately half of cancers on needle biopsy and only occasionally seen in benign glands.3, 6 These secretions are amorphous as contrasted to corpora amylacea, which are well-circumscribed round to oval structures with concentric lamellar rings. Both pink and blue secretions often coexist in the same glands. As with all of the criteria mentioned to this point, this feature is not specific for carcinoma. Rather, the presence of intraluminal secretions should be taken in context of the architectural pattern, and the nuclear and cytoplasmic features.

Prostatic crystalloids are dense eosinophilic crystal-like structures that appear in various geometric shapes such as rectangular, hexagonal, triangular, and rod-like structures (Figures 6 and 7).7, 8 Prostatic crystalloids have been reported in 25% of cancers seen on biopsy material, yet may also be seen in benign prostate acini.9 The likelihood of finding crystalloids is dependent on the number of malignant glands present and the grade; crystalloids are inversely correlated with the Gleason grade. Crystalloids, although not diagnostic of carcinoma, are more frequently found in cancer than in benign glands. The one condition that mimics cancer where crystalloids are frequently seen is adenosis, which consists of a lobule of pale staining glands. Consequently, if crystalloids are seen in small glands with an infiltrative appearance in between benign glands, where adenosis is not in the differential, they may help to establish a diagnosis of cancer. The finding of prostatic crystalloids in benign glands does not indicate an increased risk of cancer on subsequent biopsy.9

There are three features that have not, to date, been identified in benign glands, and which are in and of themselves diagnostic of cancer (Table 1). These are mucinous fibroplasia (collagenous micronodules), glomerulations, and perineural invasion (Figures 8, 9 and 10).10, 11 Occasionally, intraluminal mucinous secretions are so extensive that they become focally organized. This lesion, known as either mucinous fibroplasia or collagenous micronodules, is typified by very delicate lose fibrous tissue with an ingrowth of fibroblasts. Glomerulations consists of glands with a cribriform proliferation that is not transluminal. Rather, these cribriform formations are attached to only one edge of the gland resulting in a structure superficially resembling a glomerulus.11 Perineural invasion is, along with mucinous fibroplasia and glomerulations, one of the criteria that is diagnostic by itself of prostatic adenocarcinoma. In a series of consecutive needle biopsies containing carcinoma, 20% revealed perineural invasion.12 In order to use perineural invasion as a diagnostic criteria, the glands in question should encircle the nerve. This is to distinguish perineural invasion by carcinoma from perineural indentation that can sometimes be seen with benign glands.13, 14 Occasionally, benign prostatic glands may be seen adjacent to prostatic nerves, resulting in compression and indentation of the nerves. In these cases, the lack of circumferential growth of the glands around the nerve as well as the benign features of the gland should prevent one from misdiagnosing adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

In the evaluation of an atypical focus, the presence of several of the features can help establish a diagnosis of cancer even when limited tumor is present. In only 2% of the cases of limited tumor sent in for consultation was the diagnosis solely based on the architectural pattern.3 In these cases, when none of the features listed below are present and the diagnosis is made on the architectural pattern, one should be extremely cautious and only diagnose cancer when the pattern is overtly malignant.

Carcinomas Mimicking Benign Glands

Just as there are benign mimickers of prostate cancer, some cancers closely resemble benign prostate glands in their architectural pattern and may not be recognized as malignant.

Foamy. gland cancer must be recognized as carcinoma by its abundant foamy cytoplasm, its architectural pattern of crowded and/or infiltrative glands, and frequently present pink acellular secretions (Figure 11).15 Although the cytoplasm has a xanthomatous appearance, it does not contain lipid, but rather empty vacuoles.16 More typical features of adenocarcinoma such as nuclear enlargement and prominent nucleoli are frequently absent, which makes this lesion difficult to recognize as carcinoma. Despite its benign cytology, 96% of the cases when there is an associated non-foamy cancer, it is Gleason score >4, such that foamy gland carcinoma appears best classified as intermediate grade carcinoma. In foamy gland carcinoma, the cytoplasm is copious with nuclei occupying <10% of the cell height. Characteristically, the nuclei in foamy gland carcinoma are small, round, and densely hyperchromatic. The nuclei in foamy gland carcinoma are actually rounder than those of benign prostatic secretory cells.

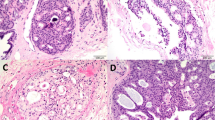

Atrophic prostate cancers are rare and may be present on needle biopsy, usually unassociated with a prior history of hormonal therapy (Figure 12).17, 18 The diagnosis of carcinoma in these cases is made on: (1) a truly infiltrative process with individual small atrophic glands situated between larger benign glands; (2) the concomitant presence of ordinary less atrophic carcinoma; and (3) greater cytologic atypia than is seen in benign atrophy.

Pseudohyperplastic prostate cancer is characterized by the presence of larger glands with branching and papillary infolding (Figure 13).19, 20 The recognition of cancer with this pattern is based on the architectural pattern of numerous closely packed glands as well as nuclear features more typical of carcinoma. A variant of pseudohyperplastic adenocarcinoma composed of markedly dilated glands with abundant cytoplasm may be particularly difficult to recognize as malignant. This form of cancer can be recognized by the appearance of numerous large glands that are almost back-to-back with straight even luminal borders, and abundant cytoplasm. Comparably sized benign glands either have papillary infoldings or are atrophic. The presence of cytologic atypia in some of these glands further distinguishes them from benign glands. It is almost always helpful to verify pseudohyperplastic cancer with the use of immunohistochemistry for high molecular weight cytokeratin. As with foamy gland cancer, pseudohyperplastic cancer, despite its benign appearance, may be associated with intermediate grade cancer and can exhibit aggressive behavior (ie extraprostatic extension).

Diagnosis of limited prostate cancer: adjunctive immunohistochemistry

There are cases that some pathologists may not feel comfortable diagnosing as adenocarcinoma based on the architectural pattern of small glands infiltrating in between larger benign glands if there is a lack of cytologic atypia. In these cases where there are a large number of atypical glands present for evaluation, the use of antibodies that label basal cells of the prostate may resolve the diagnosis (Figure 14). The most commonly used antibody used to label basal cells has been high molecular weight cytokeratin.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 More recently, antibodies to P63, which is a nuclear stain, has also been shown to label basal cells of the prostate.28, 29, 30 One study that compared high molecular weight cytokeratin and P63 have showed P63 to be slightly superior.28 In some cases, there will be faint staining of cancer glands with antibodies to high molecular weight cytokeratin; this staining is nonspecific if it is not seen in a basal cell distribution and is still supportive of a malignant diagnosis. More rarely, one can see occasional cancer cells that are strongly positive for antibodies to high molecular weight cytokeratin, yet as long as these cells are not in a basal cell distribution, these cells represent aberrant expression of the antigen in cancer. The use of high molecular weight cytokeratin when presented with only a few atypical glands is not as diagnostic, since benign glands may not show uniform positivity with this marker. Negative staining for high molecular weight cytokeratin is most diagnostic when more than a few glands are present for evaluation and the morphologic features are very suspicious for carcinoma. Rather than used to establish a diagnosis of cancer, we use the high molecular weight cytokeratin stain to help verify a suspicious focus as cancer. If we favor, although are not sure, that a focus is benign and the stain is negative, we will diagnose it as atypical rather than as cancer.

(a) Small focus of atypical glands, highly suspicious for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. (b) Stains for high molecular weight cytokeratin are negative in atypical glands, consistent with adenocarcinoma. (c) Stains for AMACR are intensely positive in the atypical glands, also consistent with adenocarcinoma. Note (lower right) a benign-appearing gland with some AMACR positivity. It is not uncommon adjacent to adenocarcinomas to have benign appearing glands that are focally positive for AMACR. These may represent early pre-neoplastic changes that are not evident morphologically.

AMACR, a cytoplasmic protein also known as P504S, has recently been recognized as a tumor marker for several cancers and although its role in prostatic carcinogenesis is unclear, several recent studies have shown that AMACR expression is significantly upregulated in prostate cancer.31, 32, 33, 34, 35 By immunohistochemistry, the majority of prostate cancers (80–100%) are positive for AMACR, although a high proportion of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), some foci of adenosis, and also some entirely benign glands have also been reported positive for this marker. As negative staining for basal cell markers especially in a small focus of atypical glands is not necessarily diagnostic of prostate cancer, positive staining for AMACR can increase the level of confidence in establishing a definitive malignant diagnosis. Although ours and previous findings confirm that AMACR is an excellent marker for the detection and diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma, caution should be applied in interpreting the immunohistochemical results. Different sensitivity and specificity have been reported among different groups. These are likely the result of the use of different antibodies, different tissue fixation, or other subtle differences in tissue preparation and methods of immunohistochemical staining. Negative AMACR staining in small suspicious glands is not necessarily sufficient for a benign diagnosis. In addition, we have demonstrated that pseudohyperplastic adenocarcinoma and atrophic adenocarcinoma of the prostate, variants of prostate cancer that are particularly difficult to diagnose, are less frequently (62–77%) positive for AMACR.

Atypical or Suspicious Prostate Needle Biopsies

We use the term ‘prostate tissue with focus of atypical glands’ to refer to small acinar structures that are suspicious for adenocarcinoma, but lack sufficient cytologic and/or architectural atypia to establish a definitive malignant diagnosis. The reasons why the focus may not be diagnostic for cancer are: (1) limited number of minimally atypical glands; (2) cannot rule out adenosis (a mimicker of cancer); (3) cannot rule out high-grade PIN, which on occasion may be difficult to tell from cancer; (4) cannot differentiate atrophy from atrophic cancers; (5) associated inflammation that can give rise to reactive atypia; and (6) crush artifact distorting the tissue. Terms like ‘atypical hyperplasia’ should not be used by pathologists as the urologist does not know if the lesion is PIN or a small focus suspicious for infiltrating cancer.

Atypical foci suspicious for cancer are seen in 3–5% of needle biopsy specimens.36, 37 Patients with an atypical diagnosis on prostate biopsy have approximately a 50% risk of cancer found on repeat biopsy.37, 38, 39 When urologists received an atypical diagnosis, we found that only 63% of men were rebiopsied, raising a concern that cancers were missed in those cases not rebiopsied after an atypical diagnosis. Although there was a trend for serum PSA to correlate with outcome of rebiopsy, this correlation was not significant and even men with serum PSA<4 had a 33% risk of cancer on rebiopsy. Men with atypical diagnoses should be rebiopsied regardless of serum PSA levels. How should the prostate be sampled on repeat biopsy to maximize detection of prostate cancer? Based on our study, we first recommend that the urologist submits all sextant biopsies in separate containers. Following an atypical diagnosis, we recommend the following routine: three cores sampled from the site of the initial atypical sextant site; two cores sampled from the adjacent atypical sextant sites; and one core from other sextant sites. The greatest likelihood of finding cancer on repeat biopsy is in the same sextant site as the initial atypical site, followed next in frequency by sextant sites adjacent to the atypical sites.40 As cancer was also detected at sites not only at or adjacent to the initial atypical biopsy, routine sampling at the time of repeat biopsy of other sites should also be conducted.

Reporting Prostate Needle Biopsies

Once a diagnosis of prostate cancer is made, the pathologist's role is critical in providing information that will both determine prognosis and therapy. The significance of various prostate findings on needle biopsy as outlined below are summarized in a recent paper by this author.41

Gleason grading will be covered in greater detail elsewhere in this issue. The following elements of the Gleason grading on needle biopsy relate to studies that have been performed at our institution. The diagnosis of Gleason score 2–4 adenocarcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy is a diagnosis that this author feels should not be made. There is poor reproducibility among experts. The vast majority of lesions diagnosed as Gleason score 2–4 on needle biopsy when reviewed by experts would be called Gleason score 5–6 or higher. Most importantly, when Gleason score 2–4 adenocarcinoma is diagnosed on needle biopsy, in many cases the tumor is not indolent. In one study, approximately half the patients with a diagnosis of Gleason score 2–4 on needle biopsy were found to have extra-prostatic extension at the time of radical prostatectomy.42 Gleason score 2–4 adenocarcinoma does exist, yet it is typically found within the transition zone as small multifocal lesions. These lesions, due to their size and location, are typically not sampled on needle biopsy. In a recent study, we have demonstrated that especially when high-grade adenocarcinoma is present, it is important to report the Gleason grade of each involved core separately.43 If one core shows Gleason score 4+4=8 adenocarcinoma and another core shows Gleason score 3+3=6, or 3+4=7, a global score reporting the entire grade for the case would be recorded as a Gleason score 4+3=7. In fact, in these cases, these tumors behave much more aggressively than Gleason score 4+3=7, and hence it is important to note that one core is involved by Gleason score 4+4=8, with other cores showing lower grade cancer. In this manner, the patient will be labeled as having a Gleason score 4+4=8 cancer for both prognostic and therapeutic standpoints.

The other role of the pathologist is to quantify the cancer found on needle biopsy.41 There are multiple ways to measure cancer on needle biopsy. These methods correlate with each other. Some studies suggest superiority of one technique over the other. A reasonable approach is to record the number of positive cores or fraction of positive cores along with one other measurement (ie percent of overall cancer, percent of each involved core by cancer, total percent of cancer, total millimeters of cancer). A limited amount of adenocarcinoma on needle biopsy by itself does not necessarily predict a limited amount of cancer within the radical prostatectomy due to sampling artifact. However, by combining a minute amount of intermediate grade cancer on needle biopsy with low serum PSA values (ie a PSA density of less than 0.15), one can achieve better prediction of clinically insignificant prostate cancer.44 These patients, depending on other factors, may be candidates for watchful waiting.

A controversial area in reporting findings on prostate needle biopsy is that regarding perineural invasion.41 Most studies have demonstrated that perineural invasion on needle biopsy is associated with an increased risk of extraprostatic extension in the radical prostatectomy. There are conflicting studies as to whether it is an independent prognostic parameter. Nonetheless, as it is readily identifiable, it is reasonable to report this finding.

While there are numerous ancillary techniques that have been proposed for cancer on needle biopsy (microvessel density, extent of neuroendocrine differentiation; proliferation, DNA ploidy), none of these findings have been shown to be independently prognostic beyond that provided by routinely measured variables (grade and extent), such that they are not suggested for clinical use at this time.

References

Epstein JI . Interpretation of Prostate Biopsies, 3rd edn. Lippincott William & Wilkins: New York, 2002.

Helpap B . Observations on the number, size, and location of nucleoli in hyperplastic and neoplastic prostatic diseases. Histopathology 1988;13:203–211.

Epstein JI . Diagnostic criteria of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy. Hum Pathol 1995;26:233–239.

Epstein JI, Fynheer J . Acidic mucin in the prostate: can it differentiate adenosis from adenocarcinoma? Hum Pathol 1992;23:1321–1325.

Goldstein NS, Qian J, Bostwick DG . Mucin expression in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the prostate. Hum Pathol 1995;26:887–891.

Humphrey PA, Vollmer RT . Corpora amylacea in adenocarcinoma of the prostate: prevalence in 100 prostatectomies and clinicopathologic correlations. Surg Pathol 1990;3:133–141.

Holmes E . Crystalloids of prostatic carcinoma: relationship to Bence–Jones crystals. Cancer 1977;39:2073–2080.

Ro JY, Ayala AG, Ordonez NG, et al. Intraluminal crystalloids in prostatic adenocarcinoma: immunohistochemical, electron microscopic, and X-ray microanalytic studies. Cancer 1986;57:2397–2407.

Henneberry JM, Kahane H, Epstein JI . The significance of intraluminal crystalloids in prostatic glands on needle biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:725–728.

McNeal JE, Alroy J, Villers A, et al. Mucinous differentiation in prostatic adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 1991;22:979–988.

Baisden BL, Kahane H, Epstein JI . Perineural invasion, mucinous fibroplasia and glomerulations: diagnostic features of limited cancer on prostate needle biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:918–924.

Bastacky SI, Walsh PC, Epstein JI . Relationship between perineural tumor invasion on needle biopsy and radical prostatectomy capsular penetration in clinical stage B adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:336–341.

Carstens PHB . Perineural glands in normal and hyperplastic prostates. J Urol 1980;123:686–688.

McIntyre TL, Frazini DA . The presence of benign prostatic glands in perineural spaces. J Urol 1986;135:507–509.

Nelson RS, Epstein JI . Prostatic carcinoma with abundant xanthomatous cytoplasm: foamy gland carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:419–426.

Tran TT, SenGupta E, Yang XJ . Prostatic foamy gland carcinoma with aggressive behavior: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:618–623.

Cina SJ, Epstein JI . Adenocarcinoma of the prostate with atrophic features. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:289–295.

Egan AJM, Lopez-Beltran A, Bostwick DG . Prostatic adenocarcinoma with atrophic features: malignancy mimicking a benign process. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:931–935.

Levi AW, Epstein JI . Pseudohyperplastic prostatic adenocarcinoma on needle biopsy & simple prostatectomy. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1039–1046.

Humphrey PA, Kaleem Z, Swanson PE, et al. Pseudohyperplastic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1239–1246.

Goldstein NS, Underhill J, Roszka J, et al. Cytokeratin 34 beta E-12 immunoreactivity in benign prostatic acini. Quantitation, pattern assessment, and electron microscopic study. Am J Clin Pathol 1999;112:69–74.

Wojno KJ, Epstein JI . The utility of basal cell specific anti-cytokeratin antibody (34 beta E12) in the diagnosis of prostate cancer: a review of 228 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:251–260.

Hedrick L, Epstein JI . Use of keratin 903 as an adjunct in the diagnosis of prostate carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:389–396.

O’Malley FP, Grignon DJ, Shum DT . Usefulness of immunoperoxidase staining with high-molecular-weight cytokeratin in the differential diagnosis of small-acinar lesions of the prostate gland. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1990;417:191–196.

Shah IA, Schlageter MO, Stinnett P, et al. Cytokeratin immunohistochemistry as a diagnostic tool for distinguishing malignant from benign epithelial lesions of the prostate. Mod Pathol 1991;4:220–224.

Brawer MK, Peehl DM, Stamey TA, et al. Keratin immunoreactivity in the benign and neoplastic human prostate. Cancer Res 1985;45:3663–3667.

Nagle RB, Ahmann FR, McDaniel KM, et al. Cytokeratin characterization of human prostatic carcinoma and its derived cell lines. Cancer Res 1987;47:281–286.

Shah RB, Zhou M, LeBlanc M, et al. Comparison of the basal cell-specific markers, 34betaE12 and p63, in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1161–1168.

Parsons JK, Gage WR, Nelson WG, et al. p63 protein expression is rare in prostate adenocarcinoma: implications for cancer diagnosis and carcinogenesis. Urology 2001;58:619–624.

Signoretti S, Waltregny D, Dilks J, et al. p63 is a prostate basal cell marker and is required for prostate development. Am J Pathol 2000;157:1769–1775.

Zhou M, Chinnaiyan AM, Kleer CG, et al. Alpha-methylacyl CoA racemase: a novel tumor marker overexpressed in several human cancers and their precursor lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:926–931.

Rubin MA, Zhou M, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. Alpha-methylacyl coenzyme A racemase as a tissue biomarker for prostate cancer. JAMA 2002;287:1662–1670.

Jiang Z, Woda BA, Rock KL, et al. P504S: a new molecular marker for the detection of prostate carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1397–1404.

Luo J, Zha S, Gage WR, et al. Alpha-methylacyl CoA racemase: a new molecular marker for prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2002;62:2220–2226.

Yang XJ, Wu CL, Woda BA, et al. Expression of alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S) in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the prostate. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:921–925.

Wills ML, Sauvageot J, Partin AW, et al. Ability of sextant biopsies to predict radical prostatectomy stage. Urology 1998;51:759–764.

Cheville JC, Reznicek MJ, Bostwick DG . The focus of ‘atypical glands, suspicious for maligancy’ in prostatic needle biopsy. Am J Clin Pathol 1997;108:633–640.

Iczkowski KA, Bassler TJ, Schwob VS . Diagnosis of ‘suspicious for malignancy’ in prostate biopsies. Urology 1998;51:749–758.

Chan TY, Epstein JI . Follow-up of atypical prostate needle biopsies suspicious for cancer. Urology 1999;53:351–355.

Allen EA, Kahane H, Epstein JI . Repeat biopsy strategies for men with atypical diagnoses on initial prostate needle biopsy. Urology 1998;52:803–807.

Epstein JI, Potter SR . The pathologic interpretation and significance of prostate biopsy findings: implications and current controversies. J Urol 2001;166:402–410.

Steinberg DM, Sauvageot J, Piantadosi S, Epstein JI . Correlation of prostate needle biopsy and radical prostatectomy Gleason grade in academic and community settings. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:566–576.

Kynz Jr GM, Epstein JI . Should each core with prostate cancer be assigned a separate Gleason score. Hym Pathol 2003;34:911–914.

Allan RW, Sanderson H, Epstein JI . Minute adenocarcinoma on prostate needle biopsy: correlation with radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2003;170:370–372.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Epstein, J. Diagnosis and reporting of limited adenocarcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy. Mod Pathol 17, 307–315 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800050

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800050

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

“Stromal cells in prostate cancer pathobiology: friends or foes?”

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

Small cell carcinoma of the bladder with coexisting prostate adenocarcinoma: two cases report and literature review

BMC Urology (2020)

-

Prostate cancer: diagnostic criteria and role of immunohistochemistry

Modern Pathology (2018)

-

Systems pathology by multiplexed immunohistochemistry and whole-slide digital image analysis

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Guidelines on processing and reporting of prostate biopsies: the 2013 update of the pathology committee of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC)

Virchows Archiv (2013)