Abstract

Nephrogenic metaplasia of the bladder and urethra has been the subject of extensive studies in recent years. However, information about ureteral involvement is still limited because of the rarity of the lesion. We described four cases of nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureter. They occurred in two men and two women whose ages ranged from 46 to 69 years. Three patients had stones, and one had multiple episodes of cystitis and chronic pyelonephritis. The lesions led to ureteral obstruction that in two patients was radiographically suspicious for carcinoma. Microscopically, three lesions were composed of tiny mucin-containing microcysts and medium-sized tubular structures lined by cuboidal cells that showed cytologic atypia characterized by enlarged vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. However, there were no mitotic figures. Two lesions invaded the full thickness of the wall of the ureter and exhibited an infiltrative growth pattern highlighted by cytokeratin stains. The remaining two lesions were confined to the lamina propria. The cells of nephrogenic metaplasia were immunoreactive to cytokeratin 7 and AE1–AE3. They lacked reactivity for monoclonal and polyclonal CEA and p53. The MIB-1-labeling index was <5%. The cytologic atypia and infiltrative growth pattern of ureteral nephrogenic metaplasia should not be misinterpreted as evidence of malignancy. All four patients are alive and symptom free 8 months to 7 years after diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Nephrogenic metaplasia, a reactive urothelial lesion composed predominantly of tubular structures superficially resembling renal tubules, usually occurs in association with chronic inflammation induced by chronic irritation or trauma to the urothelium (1, 2, 3, 4). The lesion has also been reported in renal transplant recipients (6, 7). The reactive and metaplastic nature of the lesion is supported by its frequent occurrence with prior trauma to the urothelium and occasional coexistence with intestinal metaplasia (cystitis glandularis) and endocervicosis (4). Most commonly observed in the urinary bladder, nephrogenic metaplasia can be confused with adenocarcinoma, especially in small biopsy specimens (8, 9, 10, 11). Less frequently, it has been reported in the prostatic urethra, where it may extend into the prostate and also simulate adenocarcinoma (12, 13). It has been estimated that 4% of cases of nephrogenic metaplasia occur in the ureter (2). However, the clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical features of this lesion have not been described in detail. Information about nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureters is based primarily on case reports (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21). We describe four adult patients with nephrogenic metaplasia that led to ureteral obstruction, which in two patients simulated a malignant tumor radiographically.

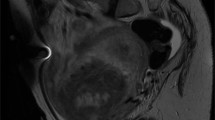

Case 1

A 62-year-old, black, diabetic woman presented with right ureteral stricture caused by complications from a stone removed endoscopically 11 years before admission. At that time, she was treated with an indwelling stent. The stent became calcified and had to be removed. However, no adequate drainage was obtained, and she underwent a percutaneous nephrostomy tube placement. An intravenous pyelogram showed that the ureteral stricture persisted and was suspicious for neoplasm (Fig. 1). An ileo-ureter was created with partial ureterectomy performed 11 years after the endoscopic removal of the stone. The patient is asymptomatic 8 months after surgical treatment.

Case 2

A 47-year-old man presented with a 6-year history of right renal colic, nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, microscopic hematuria, and an incarcerated stone in the upper portion of the right ureter. There was moderate to severe hydronephrosis. After excluding a diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, a right nephrectomy with resection of the upper segment of the ureter was performed. The patient has remained disease free 2 years after nephrectomy.

Case 3

A 46-year-old woman presented with severe left flank pain. She had a history of multiple episodes of cystitis and pyelonephritis treated with antibiotics 5 years earlier. She remained asymptomatic until 7 months before admission, when she began to have left lumbar pain. An intravenous pyelogram showed a proximal left ureteral obstruction about 3 cm from the ureteropelvic junction, with minimal hydronephrosis. A proximal segmental resection of the left ureter was performed. The patient is symptom free 5 years after resection.

Case 4

A 69-year-old man presented with right flank pain and microscopic hematuria. An intravenous pyelogram showed an irregular obstruction of the midportion of the right ureter, with proximal dilatation. These findings raised the possibility of a neoplasm or stone and were confirmed by computed tomography. Because only a portion of stone was removed endoscopically, a segmental resection of the midportion of the ureter was performed. The patient is asymptomatic 7 years after resection.

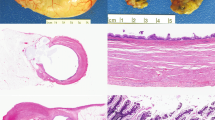

Gross Pathology

Grossly the segments of ureters revealed small, ill-defined nodular or polypoid lesions partially or completely obstructing the lumen. On sectioning, the lesions were fleshy and firm and with a heterogenous cut surface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The four cases of ureteral nephrogenic metaplasia that form the basis of this study were retrieved from the surgical pathology files of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and the consultation files of one of the authors (JAS).

Sections of the ureteral lesions were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were examined. Additional sections were obtained from the paraffin blocks for immunohistochemical stains that were performed on a Biotek Solutions Tech Mate 1000 automated immunostainer (Tucson, AZ) using the standard avidin-biotin peroxidase technique. The following antibodies were used: cytokeratins AE1-AE3, dilution 1:100, cytokeratin 7, dilution 1:100 (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA); carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), monoclonal, dilution 1:200 (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA); carcinoembryonic antigen polyclo-nal, dilution 1:400 (DAKO); MIB-1, dilution 1:100 (DAKO); p53, dilution 1:50, (DAKO). Positive and negative controls were included in each assay.

Microscopic Pathology

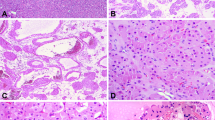

The microscopic features were essentially similar in all four cases. There was almost complete obliteration of the lumen by a small, poorly demarcated lesion that in two cases infiltrated the full thickness of the wall of the ureters (Fig. 2). The remaining two lesions were confined to the lamina propria. Microcystic structures containing mucin and medium-sized tubular structures predominated in three cases (Fig. 3). The microcysts were surrounded by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane. Both the microcysts and the tubules were lined by cuboidal cells. About 10 to 15% of these cells had large nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 4). Most microcysts and medium-sized tubular structures, however, were lined by cuboidal cells with small inconspicuous nucleoli. Long, solid tubules and large, cystically dilated structures lined by flattened or cuboidal hobnail cells were seen in one case (Figs. 5 and 6). There were no papillary structures, clear cells, or mitotic figures in any of the cases. Admixed with the tubular structures and microcysts were also inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes.

The four cases displayed immunoreactivity for cytokeratins 7 and AE1/AE3. The cytokeratin stains highlighted the infiltrative growth pattern of two lesions (Fig. 7). Both monoclonal and polyclonal CEA stains were negative. The MIB-I labeling index was <5%. Likewise, nuclear p53 protein accumulation was seen in <5% of the cells of nephrogenic metaplasia and was interpreted as negative.

DISCUSSION

Nephrogenic metaplasia of urinary bladder has been extensively studied, but limited information is available about ureteral involvement, due primarily to the rarity of the lesion. It has been estimated that approximately 55% of cases of nephrogenic metaplasia involve the urinary bladder; 41%, the urethra; and only 4%, the ureter (2). Ureteral involvement has been described in relatively large series of nephrogenic metaplasia of the urologic tract but little information about the clinical and pathological features of the ureteral lesion is provided (1, 2). In a series of 70 patients with nephrogenic metaplasia of the urologic tract, five of seven ureteral lesions were incidental findings (5).

We report here on four patients with symptomatic nephrogenic metaplasia that led to unilateral ureteral obstruction that in two cases simulated carcinoma radiographically. The radiographic resemblance of ureteral nephrogenic metaplasia to cancer has been noted by others (18). Three patients had ureteral stones, one of which was removed endoscopically 11 years before the diagnosis of nephrogenic metaplasia. The fourth patient had multiple episodes of cystitis and pyelonephritis. These clinical features support the belief that chronic inflammation caused by surgical trauma or calculi is the most common etiologic factor. In fact, inflammatory cells are a constant finding in ureteral nephrogenic metaplasia. In contrast to nephrogenic metaplasia of the bladder, which predominates in adult males, symptomatic ureteral nephrogenic metaplasia is as common in females as in males (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21). A 7-year-old male child with nephrogenic metaplasia caused by low ureteral strictures and urinary tract infection has been reported (17).

The histologic features of nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureter are similar to those of the bladder and urethra. Tubular and microcystic patterns are the most common, whereas papillary structures have been described only once in the ureter (20).

Several histologic features identified in the present study are worth mentioning because of the potential for confusion with clear cell adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell adenocarcinoma. Three of our cases showed focal cytologic atypia characterized by enlarged vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The term atypical nephrogenic metaplasia has been employed by Cheng et al. (11) for bladder lesions showing cytologic atypia and enlarged nucleoli but that have no clinical significance. We agree with those who believe that focal nuclear enlargement and prominent nucleoli are part of the morphologic spectrum of conventional nephrogenic metaplasia. Two lesions infiltrated the full thickness of the wall of the ureter, as described elsewhere (16). This infiltrative pattern, together with the presence of tiny microcysts containing mucin that resemble signet ring cells, may be misinterpreted as carcinoma. However, careful analysis allows identification of the tiny microcysts and exclusion of signet-ring cells. Moreover, no clear cells, papillary structures, or mitotic figures were noted in any of the four cases of nephrogenic metaplasia involving the ureter. To our knowledge, clear cell and signet ring cell adenocarcinomas have not been described in the ureter. In the bladder and urethra, these tumors are larger and show considerable cytologic atypia, mitotic figures, and foci of necrosis. Moreover, in contrast to clear cell carcinoma, all cases of ureteral nephrogenic metaplasia were p53 negative and showed a very low MIB-1 labeling index (<5%). These immunohistochemical findings are similar to those of Gilcrease et al. (9), who compared clear cell adenocarcinoma and nephrogenic metaplasia of the urethra and bladder and found that a high MIB-1 labeling index and strong p53 immunoreactivity favor clear cell carcinoma over nephrogenic metaplasia.

Nephrogenic metaplasia of the bladder may coexist with urothelial carcinoma and adenocarcinoma (5, 6); raising the possibility of malignant transformation. However, there is no evidence that this metaplastic lesion has malignant potential, despite the unexpected finding of similar cytogenetic abnormalities in both nephrogenic metaplasia and urothelial carcinoma (5). Other studies, however, have shown that nephrogenic metaplasia is usually a diploid lesion and that only rarely is the lesion aneuploid (11). Follow-up of patients with conventional and atypical nephrogenic metaplasia has shown that the lesion does not progress to carcinoma (11). All of our patients have remained asymptomatic 8 months to 7 years after surgical treatment, providing additional support for a benign clinical course of the lesion.

In conclusion, nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureter is often associated with incarcerated stones and chronic inflammation. The lesion usually leads to ureteral obstruction and may simulate carcinoma radiographically; it also may show both an infiltrative pattern and focal cytologic atypia. Pathologists should be aware of the morphologic features of nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureter to prevent overdiagnosis of cancer.

References

Friedman NB, Kuhlenbeck H . Adenomatoid tumors of the bladder reproducing renal structures (nephrogenic adenomas). J Urol 1950; 64: 657–670.

Oliva E, Young RH . Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: a review of the microscopic appearance of 80 cases with emphasis on unusual features. Mod Pathol 1995; 8: 722–730.

Young RH . Pseudoneoplastic lesions of the urinary bladder and urethra: a selective review with emphasis on recent information. Semin Diagn Pathol 1997; 14: 133–146.

Ayala AG, Ro JY, Amin MB, Czerniak B, Albores-Saavedra J . Urinary bladder.In: Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, editors. Pathology of incipient neoplasia. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001:p. 489–534.

Ford TF, Watson GM, Cameron KM . Adenomatous metaplasia (nephrogenic adenoma) of urothelium. Br J Urol 1985; 57: 427–433.

Tse V, Khandra M, Eisinger D, Mitterdarfer A, Boulas J, Rogers J . Nephrogenic adenoma of the bladder in renal transplant and non-renal transplant patients: A review of 22 cases. Urology 1997; 50: 690–696.

Psycha A, Milan C, Reiter WJ, Brossner C, Hartel A, Wiener H, et al. Nephrogenic adenoma in renal transplant recipient: a truly benign lesion. Urology 1998; 52: 756–761.

Alsanjari N, Lynch MJ, Fisher C, Parkinson MCL . Vesical clear cell adenocarcinoma versus nephrogenic adenoma: a diagnostic problem. Histopathology 1995; 27: 43–49.

Gilcrease MZ, Delgado R, Vuitch F, Albores-Saavedra J . Clear cell adenocarcinoma and nephrogenic adenoma of the urethra and urinary bladder: a histopathologic and immunohistochemical comparison. Hum Pathol 1998; 29: 1451–1456.

Young RH, Scully RE . Nephrogenic adenoma; a report of 15 cases, review of the literature, and comparison with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urinary tract. Am J Surg Pathol 10: 1986; 268–275.

Cheng L, Cheville JC, Sebo TJ, Eble JN, Bostwick DG . Atypical nephrogenic metaplasia of the urinary tract. A precursor lesion? Cancer 2000; 88: 853–861.

Allan CH, Epstein JI . Nephrogenic adenoma of the prostatic urethra. A mimicker of prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 802–808.

Malpica A, Ro JY, Troncoso P, et al. Nephrogenic adenoma of the prostatic urethra involving the prostate gland: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of eight cases. Hum Pathol 1994; 25: 390–395.

Lugo M, Peterson RO, Elfenbein IB, Stein BS, Duker NJ . Nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureter. Am J Clin Pathol 1983; 80: 92–97.

Jakse G, Mikuz G . Nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter. Eur Urol 1983; 9: 60–62.

Satodate R, Koike H, Sasou S, Ohori T, Nagane Y . Nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter. J Urol 1984; 131: 332–334.

Serrano BL, Vidal MT . Nephrogenic metaplasia of the ureter. Pediatr Pathol 1986; 5: 389–395.

Jackman SV, Moore RG, Nelson JB . Nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter. Endoscopic diagnosis and management. Urology 1998; 52: 316–317.

Carter A, Lynch WJ, Martin JE, Blandy P . Nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter complicating genitourinary tuberculosis. Br J Urol 1993; 71: 485–486.

Vick SR, Culkin DJ, Vick MM, Fowler M, Mata J, Venable DD . Nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter. South Med J 1993; 86: 1074–1075.

Marck J, Hradic E . Chronic sclerosing ureterites and nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter in analgesic abuse. Pathol Res Pract 1985; 180: 569–575.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gokaslan, S., Krueger, J. & Albores-Saavedra, J. Symptomatic Nephrogenic Metaplasia of Ureter: a Morphologic and Immunohistochemical Study of Four Cases. Mod Pathol 15, 765–770 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000019578.51568.24

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000019578.51568.24

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical characteristics

Virchows Archiv (2013)

-

Nephrogenic adenoma of the ureter: Case report

International Urology and Nephrology (2007)

-

PAX2: a reliable marker for nephrogenic adenoma

Modern Pathology (2006)