Abstract

Post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia and appendiceal diverticulosis simulate mucinous neoplasms, causing diagnostic confusion. Distinction between neoplasia and its mimics is particularly important since many authorities now consider all appendiceal mucinous neoplasms to be potentially malignant. The purpose of this study was to identify clinicopathologic and molecular features that may distinguish appendiceal mucinous neoplasms from non-neoplastic mimics. We retrospectively identified 92 mucinous lesions confined to the right lower quadrant, including 55 non-neoplastic examples of mucosal hyperplasia and/or diverticulosis and 37 low-grade neoplasms. Presenting symptoms, radiographic findings, appendiceal diameter, appearances of the lamina propria, non-neoplastic crypts, and epithelium, as well as mural changes were recorded. Twenty non-neoplastic lesions were subjected to KRAS mutational testing. Non-neoplastic appendices were smaller (p < 0.05) and more likely to present with symptoms of appendicitis (p < 0.05) than neoplasms. While post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia and diverticula often showed goblet cell-rich epithelium, extruded mucin pools, and patchy mural alterations with fibrosis, they always contained non-neoplastic crypts lined by mixed epithelial cell types and separated by lamina propria with predominantly preserved wall architecture. On the other hand, mucinous neoplasms lacked normal crypts (p < 0.05) and showed decreased lamina propria (p < 0.05) with diffusely thickened muscularis mucosae and lymphoid atrophy. Six (30%) non-neoplastic lesions contained KRAS mutations, particularly those containing goblet cell-rich hyperplastic epithelium. We conclude that distinction between neoplastic and non-neoplastic mucinous appendiceal lesions requires recognition of key morphologic features; KRAS mutational testing is an unreliable biomarker that cannot be used to assess biologic risk or confirm a diagnosis of neoplasia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms comprise a unique group of tumors with a propensity to disseminate to the peritoneum and cause gelatinous ascites (i.e., pseudomyxoma peritonei) despite the presence of bland cytologic features and a lack of infiltrative invasion by neoplastic epithelium. Most lesions confined to the appendix are cured by appendectomy alone, whereas those accompanied by peri-appendiceal mucin and/or neoplastic epithelium are at risk for peritoneal spread [1,2,3,4]. Importantly, mucinous neoplasms typically display circumferential growth and distention accompanied by mural scarring that obscures the tissue planes between normal layers of the appendiceal wall. These changes can make it difficult to determine the local extent of disease, especially when there are diverticulum-like herniations of neoplastic epithelium into or through the wall. For these and other reasons, there is a growing trend to consider all appendiceal mucinous neoplasms as potentially malignant. Several authors propose they be designated low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms at a minimum and have moved to eliminate “adenoma” from the nomenclature of mucinous tumors [5,6,7]. Although this approach certainly simplifies the classification of appendiceal mucinous neoplasia, it has several untoward effects, especially when non-neoplastic mucinous lesions mimic low-grade neoplasms. Patients who are adequately treated by appendectomy alone can receive an erroneous diagnosis that increases anxiety, subjects them to long-term radiologic surveillance, and in some cases, may result in unnecessary surgery or chemotherapy.

Although grossly visible mucus in combination with mucinous epithelium in the wall or peri-appendiceal tissues have been historically helpful clues to the presence of a mucinous neoplasm, these features are increasingly encountered in non-neoplastic appendices. Widespread use of high-quality cross-sectional imaging coupled with a trend toward elective appendectomy weeks to months following an episode of appendicitis (i.e., interval appendectomy) has increased detection of non-neoplastic appendiceal lesions that display many features simulating low-grade mucinous neoplasia. In fact, we have encountered numerous examples of mucosal hyperplasia with organizing appendiceal rupture and/or diverticulosis displaying extruded mucin pools and hypermucinous epithelium that closely simulate low-grade neoplasms. Distinction between these post-inflammatory changes and mucinous neoplasia is clinically important, particularly in an era of aggressive approaches to the management of appendiceal tumors. The purpose of this study is to describe the clinical, morphologic, and molecular features of non-neoplastic mucinous hyperplasia, diverticula, and post-inflammatory changes in order to determine which findings, if any, facilitate their distinction from low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms.

Materials and methods

Case selection

We searched the archives of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine from 2006 through 2018 to identify appendectomy specimens containing mucinous neoplasms, non-neoplastic mucosal hyperplasia, and diverticula. We screened all appendiceal resection specimens and eliminated those diagnosed as “no diagnostic abnormality” (or equivalent terminology), “fibrous obliteration”, and “acute appendicitis”. Cases diagnosed with interval appendicitis, chronic appendicitis, mucosal hyperplasia, diverticula, low-grade mucinous neoplasia, mucinous (cyst)adenoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and all serrated lesions were histologically reviewed. We excluded neoplasms with overlapping mucinous and serrated features, conventional (i.e., colorectal type) adenomas, serrated lesions, and simple, uninflamed diverticula. Neoplasms with overtly malignant features (e.g., complex architectural abnormalities, high-grade cytologic atypia, infiltrative growth in the appendiceal wall) and those with neoplastic epithelium and/or mucin deposits beyond the right lower quadrant were also excluded. The remaining cases were classified as either low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms or non-neoplastic lesions featuring mucosal hyperplasia using previously published criteria [8]. All non-neoplastic cases were reviewed by at least four experienced pathologists with focused interest in gastrointestinal pathology who agreed on the interpretation. Those with striking mucosal hyperplasia, mural mucin pools, and/or extramural mucin deposits were submitted entirely for histologic evaluation. Data regarding demographic information, clinical presentation, radiologic findings, and outcome were obtained from the patients’ electronic medical records. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medicine.

Pathologic evaluation

Macroscopic features of neoplastic and non-neoplastic cases were extracted from the gross descriptions of the surgical pathology reports and supportive photographic documentation when available. Data regarding appendiceal diameter, rupture, presence and location of grossly visible mucin, and any discrete lesions were recorded. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from all cases were reviewed and evaluated for the nature of mucinous epithelium (goblet vs. non-goblet mucinous cells); presence and amount of lamina propria compared with non-lesional mucosa; presence of non-neoplastic crypts, Paneth cells, and endocrine cells in lesional epithelium; thickness of the muscularis mucosae under the lesion compared with that of adjacent mucosa; fibrosis of the muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and/or muscularis propria; obliteration of planes between muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and/or muscularis propria; and presence and amount of mucosal and submucosal lymphoid tissue. The location and extent of any extraluminal mucin was recorded. Other alterations, such as non-neoplastic diverticula and fibrous obliteration of the distal appendix, were noted when present.

Molecular analysis

Twenty appendices containing non-neoplastic mucosal hyperplasia were subjected to KRAS mutational analysis in order to determine whether mutational status could help distinguish them from low-grade mucinous neoplasms. Lesional epithelium was encircled on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides prepared from routinely processed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and used to guide manual dissection of scored slides. Extraction of DNA was performed using the Promega Maxwell 16 (Promega Corp, Madison, WI) system and quantified with Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Next generation sequencing was performed using the OnCORseq Cancer Gene Mutation Panel ver.2 assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) with coverage of KRAS exons 2–4. The AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) was used for library preparation followed by template preparation and sequencing on the Ion Torrent platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Variant calls were determined using Ion Reporter Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA).

Statistical methods

Univariable analysis with Firth Penalized Maximum Likelihood method was used to compare clinicopathologic findings between non-neoplastic lesions and low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. All analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical features

Appendectomy specimens from 92 patients were included in the study; 37 harbored low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms and 55 contained non-neoplastic lesions with mucosal hyperplasia (Table 1). Most patients in both groups were older adults and women were affected more often than men, probably reflecting a greater tendency toward incidental appendectomy among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Patients with mucinous neoplasms were more likely than those with mucosal hyperplasia to present with atypical abdominal symptoms or imaging results that could not be attributed to appendicitis (27 vs. 4%, respectively, p < 0.001). Twenty-one (58%) mucinous neoplasms were incidentally detected during imaging for other indications compared with only six (11%) patients who had mucosal hyperplasia (p < 0.001). Twenty-seven (73%) mucinous neoplasms produced a radiographically apparent tumor or mucocele upon preoperative imaging compared with only 11% of non-neoplastic lesions (p < 0.001).

Patients with mucosal hyperplasia were more likely to present with symptoms related to appendicitis than those with mucinous neoplasms (72 vs. 8%, respectively, p < 0.001). Fourteen (25%) underwent appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis and 26 (47%) had an interval appendectomy following antibiotic therapy compared with 0 and 8% of patients with mucinous neoplasms, respectively (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Patients with non-neoplastic lesions more often had preoperative imaging findings suspected to represent an inflammatory process than those with mucinous neoplasms (65 vs. 14%, p < 0.001).

Follow-up information was obtained for 71 patients (mean: 47.7 months), including 40 with non-neoplastic mucinous lesions (mean: 45.5 months) and 31 with low-grade mucinous neoplasms (mean: 50.6 months). None of the patients in either group developed peritoneal recurrence or any evidence of mucinous neoplasia during the follow-up period.

Pathologic features

The gross and histologic characteristics of non-neoplastic lesions and mucinous neoplasms are summarized in Table 2. Mucinous neoplasms produced grossly evident abnormalities suggesting the presence of a neoplasm in almost all cases (Fig. 1a). Thirty-three (89%) were associated with appendiceal dilatation compared with only 14 (25%) non-neoplastic mucinous lesions (p < 0.001). The degree of appendiceal dilatation was also greater among neoplasms than non-neoplastic cases (mean: 2.4 cm vs. 1.3 cm, p < 0.001) with more frequent diffuse, fusiform enlargement of the appendix (49 vs. 5%, p < 0.001). Thirty-three (89%) neoplasms contained thick, tenacious mucus, whereas non-neoplastic appendices featured visible mucin in only 11% of cases (p < 0.001). In contrast, non-neoplastic appendices were far more likely to display visible changes of appendicitis or diverticula with preserved layers of the appendiceal wall (Fig. 1b). Thirty-one (56%) featured adhesions, fibrinous exudates, or erythema compared with only eight (22%) mucinous neoplasms (p = 0.001).

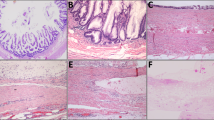

Mucinous neoplasms frequently cause fusiform enlargement of the appendix due to accumulation of thick tenacious mucus (a). Non-neoplastic appendices show minimal dilatation with preserved layers of the wall and small cysts (arrows) representing diverticula (b). Mucinous neoplasms display circumferential involvement of the lumen (c) with obliterated tissue planes between the layers of the appendiceal wall (d). Ruptured diverticula feature focal disruption of an otherwise normal muscularis propria (e). The muscularis mucosae is of near normal thickness and is clearly separated from the submucosa (f).

Low-grade mucinous neoplasms displayed circumferential involvement of the inner appendix by flat, undulating, or papillary epithelium with decreased or absent lamina propria, whereas non-neoplastic cases featured incomplete luminal involvement by mucin-rich epithelium; supportive lamina propria was consistently present (Fig. 1c–f). Mucinous neoplasms were often accompanied by a diffusely thickened, rind-like muscularis mucosae (n = 33, 89%) with a complete lack of lymphoid tissue in 68% of cases (Fig. 2a). Submucosal fibrosis was present in 33 (89%) neoplasms, obscuring the interface between the submucosa and muscularis propria in most (81%) of these. Mucinous neoplasms contained non-goblet, barrel-shaped columnar cells with faintly basophilic mucin and enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 2b).

Mucinous neoplasms are often accompanied by a diffusely thickened, rind-like muscularis mucosae with a lack of lymphoid tissue and decreased lamina propria (a). The epithelium consists of barrel-shaped columnar cells with faintly basophilic mucin and enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei (b). Non-neoplastic lesions contain normal lamina propria supported by muscularis mucosae as well as non-neoplastic crypts (c). Increased numbers of goblet cells are present in the epithelium, which also contains scattered Paneth cells in the crypts (d).

On the other hand, non-neoplastic lesions showed a greater tendency toward preservation of normal elements when compared with low-grade mucinous neoplasms (Fig. 2c). They almost always featured evenly dispersed non-neoplastic crypts (96%) supported by lamina propria (96%, p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Normal amounts of mucosal and submucosal lymphoid tissue were present in 65% of cases (p = 0.003). The muscularis mucosae was normal in most areas (p = 0.005) with only patchy thickening and fibrosis in 29 (53%) cases, particularly in association with diverticula. Although submucosal fibrosis (67%) and obliterated tissue planes between the submucosa and muscularis propria (51%) were not infrequent among non-neoplastic lesions, these changes were focal rather than circumferential (p = 0.02 and p = 0.01, respectively). Non-neoplastic lesions were composed of hypertrophic goblet cells admixed with non-goblet columnar cells; non-goblet mucin-containing cells were not detected in any cases (Fig. 2d). Scattered Paneth cells were identified in 18% of non-neoplastic cases compared with only 3% of mucinous neoplasms (p = 0.045). Clearly recognizable diverticula lined by non-neoplastic epithelium were present distant from areas of mucinous epithelium and/or extracellular mucin in 76% non-neoplastic appendices compared with only 19% of mucinous neoplasms (p < 0.001). Organizing peri-appendiceal inflammation was also more commonly associated with non-neoplastic lesions than mucinous neoplasms (55 vs. 32%, respectively, p = 0.05).

Although extra-appendiceal mucin was frequently observed in association with both ruptured, non-neoplastic appendices (45%) and mucinous neoplasms (62%), its nature was qualitatively different in these situations. Ruptured non-neoplastic appendices featured mucin pools accompanied by appendiceal perforation with organizing abscesses, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, and frequent macrophages or multinucleated giant cells. They were present in direct continuity with ruptured diverticula in 16 (64%) cases and frequently surrounded by a lymphohistiocytic cuff (n = 14, 56%) with an ingrowth of granulation tissue (n = 13, 52%). Only three (12%) cases featured extra-appendiceal epithelium, which was scant and composed of goblet and non-goblet epithelial cells. In contrast, mucin pools associated with mucinous neoplasms generally lacked the exuberant inflammatory response typical of non-neoplastic cases; only 13 (57%) were associated with chronic inflammation, which was generally mild and focal. Mucinous neoplasms more frequently featured hyalinizing fibrosis (n = 20, 87%, p < 0.001). Extra-appendiceal epithelium was detected in 10 (43%) mucinous neoplasms and was morphologically similar to the mucinous epithelium of the lesion (p = 0.02).

Molecular characteristics

Twenty non-neoplastic mucinous lesions were subjected to KRAS mutational analysis. Six (30%) were found to harbor KRAS alterations; there were five codon 12 mutations and one codon 13 mutation. The variant allele frequency in these six cases ranged from 5 to 22% with a mean of 10%. As a group, lesions containing KRAS mutations tended to occur among slightly older adults (mean: 60 years) and produced minimal or mild appendiceal dilatation (mean: 1.1 cm). All of these cases were entirely submitted for histologic evaluation. They frequently featured goblet cell-rich hyperplastic epithelium but were otherwise similar to non-neoplastic mucinous lesions with wild-type KRAS (Fig. 2d).

Discussion

Delayed appendectomy following a course of antibiotic therapy is increasingly common among patients who present with uncomplicated appendicitis or a perforated appendix because this approach is associated with less morbidity than immediate appendectomy [9,10,11,12]. While some authors have described Crohn-like inflammatory changes in interval appendectomy specimens, little attention has been given to the proliferative epithelial changes that occur during the resolution of appendicitis [13]. In our experience and that of others, exuberant non-neoplastic epithelial proliferations and ruptured diverticula that develop in this setting can bear a close resemblance to low-grade mucinous neoplasia [14]. Hsu et al. described 11 cases of ruptured appendiceal diverticula, all of which were originally interpreted to represent, or were concerning for, appendiceal mucinous neoplasms [8]. Valasak et al. found an overall concordance rate of only 69% with respect to the diagnosis of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in their consultation material; misinterpretation of post-inflammatory changes by the submitting pathologist accounted for all cases with major discrepancies [15]. Similarly, Arnold et al. reported that 44% of appendices submitted to their consultation practices were classified as low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms by the referring pathologist but more than half of these cases were considered to be non-neoplastic by the consultants [16]. In fact, we suspect that many reports in the surgical literature describing a high rate of mucinous neoplasia in interval appendectomy specimens actually represent post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia with hypermucinous epithelium [17,18,19]. This view is supported by data from other studies showing similar rates of neoplasia in interval and immediate appendectomy specimens. Lai et al. reviewed 70 interval appendectomy specimens from patients who presented with an inflammatory mass and found the incidence of neoplasia to be only 2%. Notably, 8% of their cases featured exuberant proliferations of non-neoplastic, mucin-rich epithelium [20].

Distinction between mucinous neoplasia and its mimics is critically important. The former requires surveillance imaging and potential surgery or chemotherapy depending on extent of disease, whereas non-neoplastic lesions are cured by appendectomy and require no future interventions or surveillance. We identified several key features that aid distinction between post-inflammatory mucinous hyperplasia and mucinous neoplasia. Most (75%) patients with non-neoplastic lesions are clinically suspected to have appendicitis based on either symptoms (72%) or radiographic evidence of an inflammatory process (63%), and the majority have gross evidence of appendicitis (56%). The layers of the appendiceal wall are generally preserved and the muscularis mucosae and lamina propria are mostly normal; fibrosis is limited to diverticula or areas of organizing inflammation. Non-neoplastic appendices contain lymphoid aggregates that are morphologically similar to those present in normal appendices from healthy adults. They contain mucin-rich surface epithelium that may assume a slightly villiform architecture with goblet and non-goblet cells as well as scattered crypts lined by non-neoplastic epithelial cells. On the other hand, low-grade mucinous neoplasms almost always produce a radiographically or grossly evident mass (92%) featuring barrel-shaped, acid mucin-containing epithelial cells unaccompanied by non-neoplastic crypts. The lamina propria is uniformly decreased or entirely absent; neoplasms are supported by a thick, fibrotic muscularis mucosae with decreased lymphoid tissue and obliterated tissue planes between layers of the wall.

Similar to our results, Lowes et al. recently described a series of 74 appendiceal diverticula and found that non-neoplastic crypts, preserved mucosal architecture with lamina propria, and a lack of nuclear abnormalities distinguished these cases from low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms [14]. These authors also emphasized the importance of clinical information in the assessment of appendiceal mucinous lesions; only 11% of their diverticulosis cases showed any features that raised clinical suspicion for a neoplasm. Our detailed analysis of clinical records found that, in contrast to previous reports, patients with mucinous neoplasms rarely present with classic symptoms of acute appendicitis [21,22,23]. Rather, neoplasms are accompanied by vague, often unrelated, abdominal symptoms that generate a broad differential diagnosis and prompt abdominal imaging studies. Most neoplasms are radiographically visible, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. Our observations are in line with those of Gundogar et al. which found that most mucinous neoplasms are asymptomatic and incidentally detected during imaging studies performed for other reasons [24]. Similar to results of others, we also found that dilated appendices (>2 cm luminal diameter) are more likely to contain mucinous neoplasms [22, 24, 25]. Only 4 (7%) appendices spanning more than two centimeters in diameter were associated with non-neoplastic lesions in our series and none of our non-neoplastic cases showed diffuse, fusiform appendiceal dilatation. We did not find a significant association between mucinous neoplasia and the presence of acquired, non-neoplastic diverticula, as has been described in other studies [26,27,28]. Rather, we identified non-neoplastic diverticula in 76% of post-inflammatory appendices compared with only 19% of appendices containing mucinous neoplasms.

Of note, our data suggest that molecular assays are of limited value with respect to distinguishing post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia from appendiceal neoplasia. The most common molecular alterations detected in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms affect KRAS with reported mutational rates ranging from 41 to 100% compared with 0% in the normal mucosa [29,30,31,32,33]. Other mutations affecting GNAS are less common, occurring in 35–50% of cases [29, 34, 35]. Ours is the first study to investigate molecular alterations in appendices that display post-inflammatory, hyperplastic changes with increased numbers of goblet cells. Not surprisingly, we found a relatively high (30%) frequency of KRAS mutations at variant allele frequencies ranging up to rates observed in neoplasms (mean: 10%, range: 5–22%). We suspect these alterations arise via mechanisms similar to those of other proliferative lesions throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Goblet cell-rich hyperplastic polyps of the colon harbor KRAS mutations in up to 46% of cases, and KRAS mutations can be detected in non-dysplastic proliferative mucosae of patients with chronic colitis [36,37,38]. Molecular changes affecting KRAS have also been reported in hyperplastic polyps of the small intestine and stomach, as well as low-grade pancreatic intraepithelial lesions (i.e., PanIN1) in patients with chronic pancreatitis who do not have invasive adenocarcinoma [39,40,41,42,43,44]. We conclude that KRAS alterations are commonly observed in non-neoplastic conditions that feature mucosal hyperplasia and advise against the use of currently available molecular techniques to establish a diagnosis of neoplasia.

Post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia and diverticula are increasingly encountered in appendectomy specimens, particularly as the practice of interval appendectomy becomes more widespread. These changes feature proliferative epithelium with increased goblet cells, extruded mucin pools, and patchy mural alterations with fibrosis. Although these changes simulate low-grade mucinous neoplasia, several key features reliably distinguish between non-neoplastic and neoplastic conditions. Mature goblet cells in the surface epithelium, goblet cell-rich crypts containing interspersed Paneth cells, supportive lamina propria, intact muscularis mucosae of normal thickness, and readily discernible layers of the appendiceal wall distant from areas of perforation and diverticula are all significantly more common in resolving inflammatory conditions than low-grade mucinous neoplasms. The presence of these features should alert the pathologist to the likelihood of non-neoplastic condition and prompt review of pertinent clinical and radiographic information. Correct classification of disease is particularly important since many pathologists now consider all mucinous neoplasms of this site to be potentially malignant, warranting long-term radiographic surveillance, and in some cases, additional therapeutic interventions.

References

Smeenk RM, van Velthuysen MLF, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FAN. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:196–201.

Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, Balis UJ, Young RH. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1089–103.

Pai RK, Longacre TA. Appendiceal mucinous tumors and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12:291–311.

Carr NJ, Finch J, Ilesley IC, Chandrakumaran K, Mohamed F, Mirnezami A, et al. Pathology and prognosis in pseudomyxoma peritonei: a review of 274 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:919–23.

Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, Sobin LH, Sugarbaker PH, Gonzalex-Moreno, et al. A consensus for classification and pathologic reporting of pseudomyxoma peritonei and associated appendiceal neoplasia: the results of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:14–26.

Carr NJ, Bibeau F, Bradley RF, Dartigues P, Feakins RM, Geisinger KR, et al. The histopathological classification, diagnosis and differential diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal neoplasms, appendiceal adenocarcinomas and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Histopathology. 2017;71:847–58.

Bosnan FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND (Eds). WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Fourth Edition. Lyon, France: IACR WHO Classification of Tumours; 2010.

Hsu M, Young RH, Misdraji J. Ruptured appendiceal diverticula mimicking low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1515–21.

Oliak D, Yamini D, Udani VM, Lewis RJ, Arnell T, Vargas H, et al. Initial nonoperative management for periappendiceal abscess. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:936–41.

Simillis C, Symeonides P, Shorthouse AJ, Tekkis PP. A meta-analysis comparing conservative treatment versus acute appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (abscess or phlegmon). Surgery. 2010;147:818–29.

Mentula P, Sammalkorpi H, Leppäniemi A. Laparoscopic surgery or conservative treatment for appendiceal abscess in adults? A randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2015;262:237–42.

Andersson RE, Petzold MG. Nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:741–8.

Guo G, Greenson JK. Histopathology of interval (delayed) appendectomy specimens: strong association with granulomatous and xanthogranulomatous appendicitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1147–51.

Lowes H, Rowaiye B, Carr NJ, Shepherd NA. Complicated appendiceal diverticulosis versus low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a major diagnostic dilemma. Histopathology. 2019;75:478–85.

Valasek MA, Thung I, Gollapalle E, Hodkoff AA, Kelly KJ, Baumgartner JM, et al. Overinterpretation is common in pathological diagnosis of appendix cancer during patient referral for oncologic care. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179216.

Arnold CA, Graham RP, Jain D, Kakar S, Lam-Himlin DM, Naini BV, et al. Knowledge gaps in the appendix: a multi-institutional study from seven academic centers. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:988–96.

Carpenter SG, Chapital AB, Merritt MV, Johnson DJ. Increased risk of neoplasm in appendicitis treated with interval appendectomy: single-institution experience and literature review. Am Surg. 2012;78:339–43.

Schwartz JA, Forleiter C, Lee D, Kim GJ. Occult appendiceal neoplasms in acute and chronic appendicitis: A single-institution experience of 1793 appendectomies. Am Surg. 2017;83:1381–5.

Furman MJ, Cahan M, Cohen P, Lambert LA. Increased risk of mucinous neoplasm of the appendix in adults undergoing interval appendectomy. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:703–6.

Lai HW, Loong CC, Chiu JH, Chau GY, Wu CW, Lui WY. Interval appendectomy after conservative treatment of an appendiceal mass. World J Surg. 2006;30:352–7.

Pai RK, Beck AH, Norton JA, Longacre TA. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: clinicopathologic study of 116 cases with analysis of factors predicting recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1425–39.

Carr NJ, McCarthy WF, Sobin LH. Epithelial noncarcinoid tumors and tumor‐like lesions of the appendix. A clinicopathologic study of 184 patients with a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 1995;75:757–68.

Järvinen P, Lepistö A. Clinical presentation of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Scand J Surg. 2010;99:213–6.

Gundogar O, Kimiloglu E, Komut N, Cin M, Bektas S, Gonullu D, et al. Evaluation of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms with a new classification system and literature review. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:533–42.

Tirumani SH, Fraser-Hill M, Auer R, Shabana W, Walsh C, Lee F, et al. Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix: A current comprehensive clinicopathologic and imaging review. Cancer Imaging 2013;13:14–25.

Medlicott SAC, Urbanski SJ, Urbanski SJ. Acquired diverticulosis of the vermiform appendix: a disease of multiple etiologies. A retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 1998;6:23–7.

Lamps LW, Gray GF, Dilday BR, Washington MK. The coexistence of low-grade mucinous neoplasms of the appendix and appendiceal diverticula: a possible role in the pathogenesis of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:495–501.

Dupre MP, Jadavji I, Matshes E, Urbanski SJ. Diverticular disease of the vermiform appendix: a diagnostic clue to underlying appendiceal neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1823–6.

Liu X, Mody K, De Abreu FB, Pipas JM, Peterson JD, Gallagher TL, et al. Molecular profiling of appendiceal epithelial tumors using massively parallel sequencing to identify somatic mutations. Clin Chem. 2014;60:1004–11.

Zauber P, Berman E, Marotta S, Sabbath-Solitare M, Bishop T. Ki-ras gene mutations are invariably present in low-grade mucinous tumors of the vermiform appendix. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:869–74.

Kabbani W, Houlihan PS, Luthra R, Hamilton SR, Rashid A. Mucinous and nonmucinous appendiceal adenocarcinomas: different clinicopathological features but similar genetic alterations. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:599–605.

Davison JM, Choudry HA, Pingpank JF, Ahrendt SA, Holtzman MP, Zureikat AH, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of disseminated appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: identification of factors predicting survival and proposed criteria for a three-tiered assessment of tumor grade. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1521–39.

Zissin R, Gayer G, Fishman A, Edelstein E, Shapiro-Feinberg M. Synchronous mucinous tumors of the ovary and the appendix associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:311–6.

Hara K, Saito T, Hayashi T, Yimit A, Takahashi M, Mitani K, et al. A mutation spectrum that includes GNAS, KRAS and TP53 may be shared by mucinous neoplasms of the appendix. Pathol Res Pr. 2015;211:657–64.

Nishikawa G, Sekine S, Ogawa R, Matsubara A, Mori T, Taniguchi H, et al. Frequent GNAS mutations in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:951–8.

Srivastava A, Redston M, Farraye FA, Yantiss RK, Odze RD. Hyperplastic/serrated polyposis in inflammatory bowel disease: a case series of a previously undescribed entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:296–303.

Guarinos C, Sánchez-Fortún C, Rodríguez-Soler M, Alenda C, Payá A, Jover R. Serrated polyposis syndrome: Molecular, pathological and clinical aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2452–61.

Yang S, Farraye FA, Mack C, Posnik O, O’Brien MJBRAF. and KRAS mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1452–9.

Saab J, Estrella JS, Chen YT, Yantiss RK. Immunohistochemical and molecular features of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Adv Cytol Pathol. 2017;2:00012.

Dijkhuizen SMM, Entius MM, Clement MJ, Polak MM, Van Den Berg FM, Craanen ME, et al. Multiple hyperplastic polyps in the stomach: evidence for clonality and neoplastic potential. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:561–6.

Rosty C, Buchanan DD, Walters RJ, Carr NJ, Bothman JW, Young JP, et al. Hyperplastic polyp of the duodenum: A report of 9 cases with immunohistochemical and molecular findings. Hum Pathol 2011;42:1953–9.

Todoric J, Antonucci L, Di Caro G, Li N, Wu X, Lytle NK, et al. Stress-activated NRF2-MDM2 cascade controls neoplastic progression in pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:824–39.

Higa E, Rosai J, Pizzimbono CA, Wise L. Mucosal hyperplasia, mucinous cystadenoma, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the appendix. A re‐evaluation of appendiceal “mucocele”. Cancer. 1973;32:1525–41.

Rashid S, Singh N, Gupta S, Rashid S, Nalika N, Sachdev V, et al. Progression of chronic pancreatitis to pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2018;47:227–32.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funding by the translational research program through the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hissong, E., Goncharuk, T., Song, W. et al. Post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia and appendiceal diverticula simulate features of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Mod Pathol 33, 953–961 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0435-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0435-1