Abstract

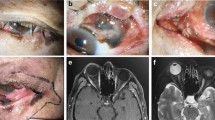

Orbital exenteration aims at local control of disease invading the orbit that is potentially fatal or relentlessly progressive. Of all exenterations presenting to ophthalmologists, 40–50% are required for tumours in the eyelid or periocular skin. 99% of these are basal cell carcinomas and 4–6% each are squamous cell carcinomas or sebaceous gland carcinomas. Orbital invasion results in progressive fixation of the tumour to bone and reduced ocular motility. Perineural invasion of branches of the trigeminal nerve leads to numbness or pain, and that the facial nerve, to weakness. Biopsy identifies the cell type and the presence of perineural invasion. CT and MRI scanning help in the assessment of tumour spread within the orbit. Management should be in collaboration with an oncologist. Exenteration may be total–the removal of all orbital contents–or lid-sparing if the tumour is placed posteriorly. The socket may be allowed to heal by granulation or lined with a split skin graft or local flap. Complications may be seen following 20–25% of exenterations and include fistulae, tissue necrosis, exposed bone, and infection. Incomplete clearance of tumours occurs in about 38% of total exenterations and 17% of subtotal. The overall 5-year survival is 55–65%, but significantly worse if there was perineural spread. Facial prostheses may be mounted on glasses or secured with tissue glue or osseointegrated implants. Excellent cosmetic results can be achieved but many patients prefer to wear a patch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Orbital exenteration implies the removal of all the orbital contents including the periorbita and eyelids.

An operation similar to modern exenteration was probably described by Bartisch in 1583 (cited by Goldberg et al1). Frezzotti et al2 reviewed the history of exenteration; he attributed the first description to Gooch in 1767.

Modern exenteration aims to achieve local control of the orbital disease. ‘Total’ exenteration as defined above is often needed, but when possible, orbital tissue is conserved and eyelid skin and orbicularis muscle are spared to aid healing.1, 3, 4 If the bone of the orbit is invaded, an ‘extended’ exenteration is required that includes resection of diseased bone.4, 5

Indications

Exenteration surgery is necessary when orbital and periorbital tumours, and occasionally other conditions, that are potentially fatal or relentlessly progressive cannot be treated more effectively in other ways.

About 40–50% of exenterations that present to ophthalmologists are required for tumours originating in the eyelid or periocular skin.1, 4, 6, 7 The remainder originate almost exclusively in the conjunctiva, orbit, or globe. Tumours arising in the paranasal sinuses and nose may also require exenteration to achieve local control, but these tumours usually do not present to an ophthalmologist. The case mix of disease leading to exenteration varies with the special interests of the treatment centre.3

The relative incidence of periocular skin malignancies varies with geographical area and racial group.8, 9, 10 Basal cell carcinoma is universally the most common malignant skin tumour accounting for approximately 90% in most series; squamous cell and sebaceous gland carcinoma occur in approximately 4–6% each. The incidence of all skin malignancy is increasing worldwide.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma occur most commonly in the lower lid and medial canthus.9, 17, 18 Sebaceous gland carcinoma is most common in the upper lid.19 Other eyelid malignancies are relatively rare.

Any periocular skin malignancy, if neglected, can invade the orbit and raise the probability of exenteration. The incidence of orbital invasion is about 2–4%,20, 21, 22 and the risk factors include multiple recurrences, large size, aggressive histological subtype, perineural spread, canthal location—particularly the medial canthus—, and older patients.22, 23, 24, 25 Exenteration for sebaceous gland carcinoma is more likely to be required if there is intraepithelial (pagetoid) spread of the tumour.26

Perineural invasion occurs in less than 1% of basal cell carcinomas,18, 27 but in about 3–14% of squamous cell carcinomas.17, 28 It is more common in lesions of the forehead and brow29, 30 and with aggressive cell types.23, 24, 28, 31

Clinical signs

There may be no signs of orbital invasion in the early stages, although a mass is almost always palpable.23 As the disease progresses fixation to bone, limitation of ocular motility and globe displacement may occur.22, 23, 29 Spread through the periorbita into bone has been reported in 20–30% of cases.4, 23 Perineural spread is also asymptomatic in the early stages, but eventually results in numbness or, less frequently, pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve—especially the supraorbital nerve in periocular tumours. Branches of the facial nerve are also frequently involved.29, 30 As posterior spread continues, the orbital apex and cavernous sinus become involved with predictable accompanying clinical signs.

Investigation

Biopsy of the surface tumour is helpful to establish the cell type and to identify perineural invasion. Biopsy of the supraorbital nerve may be helpful to confirm the presence and extent of perineural invasion in tumours of the forehead or brow.30

CT and MR imaging are useful in assessing the extent of orbital spread. CT is more appropriate for bone destruction, MRI demonstrates the extent of soft tissue invasion and can sometimes detect the integrity of the periorbita—the most effective barrier to tumour spread.22, 23, 32, 33

Management of orbital invasion

Having diagnosed malignant orbital invasion, it is always appropriate to collaborate with a multidisciplinary team in planning management. An oncologist should always be involved and also other disciplines according to the extent and direction of tumour invasion. Radical surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy may be needed. Occasionally, surgery is not the best management and this can be decided jointly.

Choice of operation

The aim of exenteration is to achieve local control of the disease.

Total exenteration removes all orbital tissue, including the periorbita, posterior to the orbital rim. The eyelids may be preserved in tumours placed posteriorly within the orbit and even some arising in periocular skin. Most anteriorly placed tumours, however, require removal of all anterior orbital tissue and periorbita together with the eyelids, but the posterior orbital tissues may be preserved. If there are macroscopic changes at operation suspicious of bone invasion, it is helpful to have a frozen section examination of the periorbita. If it is positive, bone should be removed and sent for decalcification and pathological analysis.

Shields et al3 reported 56 exenterations. Four of the nine skin tumours allowed some eyelid sparing; in 22 of the 24 conjunctival tumours and all of the 11 orbital tumours, the eyelids were spared. Ben Simon et al4 reported 34 exenterations: 13 were subtotal, 14 were total, and seven were extended.

In planning the surgery, the extent of orbital invasion—which may have been underestimated by the investigations—the biological behaviour of the tumour, and the presence of perineural spread must be taken into account. Aggressive cell types and in particular the possibility of perineural invasion should prompt generous margins of excision.

Techniques

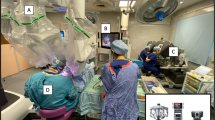

Exenteration including the eyelids34, 35

The orbital rim is marked and the skin and tissues are incised down to the periosteum. The periosteum is incised for 360° and reflected from the orbital rim then posteriorly within the orbit to behind the globe. Special care is taken along the thin medial wall and orbital roof. The orbital tissues are transected at a point posteriorly that allows safe clearance of the tumour. The lacrimal sac is removed with the exenterated orbital tissues. The nasolacrimal duct is tied off. If there is macroscopic evidence of bone involvement, the affected bone is removed with rongeurs or a saw. The skin and muscle are approximated medially and laterally at the orbital rim to reduce the skin aperture.

Management of the exenterated orbit without lid sparing

The exposed bone of the exenterated orbit may be treated in a variety of ways.

The orbit heals by granulation in 3–4 months.3, 4, 36 Frequent dressings with antibacterial packs are needed. Healing by granulation results in a shallower socket than with split skin grafting.

Split skin, with or without meshing, generally heals well.1, 35, 37 Full-thickness skin grafts should not be used, as the secretions can be profuse and unpleasant.

The transposed forehead flap is one of a number of vascularised flaps, which have been described to fill the orbit.38, 39, 40 Free tissue transfers have also been used. These are particularly effective if large defects in the orbital walls have to be covered or if radiotherapy has been used or is planned. Temporalis muscle flaps are covered with a split skin graft. Shallow sockets result with these techniques and a prosthesis may be difficult or impossible to wear.

Lid sparing exenteration1, 3, 4

Incisions are made 1 mm from the lashes in the upper and lower lids. Dissection is preferably deep to the orbicularis muscle, but it can be at a more superficial level between the skin and orbicularis muscle if tumour clearance would be compromised by a deeper level of dissection. At the orbital rim, the periosteum is incised 360° and the exenteration proceeds as above.

Management of the exenterated orbit with lid sparing

The skin–muscle flaps preserved from the eyelids are sutured together, with local undermining if necessary. A drain is not usually needed. Local advancement or other flaps may be needed to achieve closure without excess tension. Separation of the sutured flaps occurs occasionally; they can be resutured with further undermining or allowed to heal by granulation. Healing is significantly shorter following lid sparing than with simple granulation.3

Clearance of tumours

It is not always possible to achieve complete clearance of a tumour despite radical surgery. Incomplete clearance was found in 38% of total and 17% of subtotal exenterations by Goldberg et al.1 Perineural invasion may indicate more extensive spread than anticipated, the risk of incomplete clearance is higher and the prognosis is worse.21, 29

Complications

Ben Simon et al4 reported complications in 23.5% of 34 exenterations. These include fistula formation into a sinus, the nose or the nasolacrimal duct, tissue necrosis with eschar formation, chronic drainage, infection, chronically exposed bone, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and pain. Large fistulae and exposed bone can be managed with a temporalis muscle flap38 or other local flap. The time taken for healing with granulation can occasionally far exceed the usual 3–4 months.3 Split skin usually takes well but occasionally some skin is lost owing to infection or haematoma or following irradiation.41 Crusting and general cleanliness of the socket can be a problem. Careful attention to daily hygiene is necessary. Crusting can be managed with dilute potassium permanganate (1 : 10 000) packs supplemented with Trimovate ointment (clobetasone butyrate 0.05%, oxytetracycline, nystatin). Less commonly, a cerebrospinal fluid leak may result from cautery or other trauma to the orbital roof.42, 43

Patch or prosthesis?

Most patients prefer to wear a patch after exenteration, rather than a prosthesis, especially with the larger reconstructions.1, 3, 4, 35, 40

Attempts have been made to preserve more of the orbital tissues including palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva to achieve reconstruction of a socket, which allows retention of a standard ocular prosthesis (simple artificial eye) using mucosal grafts in addition if needed.1 This is feasible in only a small minority of exenterated patients.

If a standard postexenteration facial-type prosthesis is preferred to a patch, good cosmesis can be achieved. The prosthesis is moulded to the underlying socket and may include components to close any communication with the nose or sinuses. Fixation of the prosthesis may be with tissue glue or it may be mounted on spectacles. Tissue glue is inefficient and glue deposits are left on the prosthesis, which may discolour. Spectacle-mounted prostheses prevent the spectacles ever being removed in public. Patients often lose confidence with these methods and tend to abandon their prosthesis for a patch.

An alternative method of prosthesis fixation is the use of titanium osseointegrated implants to which the prosthesis is attached by magnets or clips.44 The technique was pioneered by Brånemark in Sweden and it has proven to be a very successful method of fixation for facial and other prostheses.

The implants are usually placed once the orbit is healed. The procedure is in two stages. Three or four titanium fixtures are implanted into the bony orbital rim and covered again with skin while osseointegration occurs. About 4 months later, the skin over the implants is opened, healing of the skin around the implant is allowed to occur, and then the final magnets or framework for prosthesis fixation are fitted (Figure 1). The mould of the socket is taken at this stage and the prosthesis is made44, 45 (Figure 2). Osseointegration also occurs in irradiated orbits, but it is less reliable and it is advisable to delay implantation for at least a year following irradiation.44, 46 Patient satisfaction with implant-retained prostheses is generally high45 (Figures 3 and 4).

Prognosis

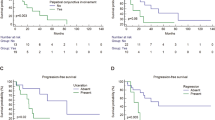

Mohr and Esser5 reported a 1-year survival of 89%, a 5-year rate of 63%, and a 10-year rate of 48% in 77 exenterations, 58% of whom required simultaneous bone removal.

Bartley et al47 reported 5-year recurrence and survival rates in patients with and without known residual tumour. Eighty-two per cent had no residual tumour at operation, and in this group, the 1-year survival was 88.6%, the 5-year survival was 56.8%, and at 5 years, 48.3% remained clear of local recurrence and metastases. Eighteen per cent had known residual local tumour or metastasis at operation. The 1-year survival in this group was 55.0% and the 5-year survival was 25.8%.

Savage25 reported 11 exenterations in patients with large squamous or basal cell carcinomas of the skin. The recurrence rate was 60% and the 5-year survival was 56%.

Perineural tumour spread has a worse prognosis. McNab et al29 reported 21 patients with perineural spread of squamous cell carcinoma. The primary tumour was most commonly found in the forehead or brow; 95.2% had altered or reduced sensation, 42.9% had pain, 66.7% had ophthalmoplegia. 66.7% had involvement of the facial nerve, and 66.7% died between 9 months and 5 years, one was alive at 3 years but with recurrent disease. Two were alive at 14 and 18 years. Four had no recurrence at 2, 3, 4, and 12 months.

Williams et al33 reported 35 patients with clinical perineural spread. 51.4% had positive evidence of perineural spread on imaging. The 5-year survival in this group was 50%. In the group without CT or MR confirmation of perineural spread, the 5-year survival was 86%.

Conclusion

Exenteration is a radical operation for potentially fatal or relentlessly progressive disease that has invaded the orbital tissues. Clearance is achieved in more than 60% of total exenterations and more than 80% of subtotal exenterations. The 5-year survival is about 55–65% for exenterations that present to ophthalmologists:tumours arising in the skin, globe, or orbital tissues. Survival is significantly lower if there is perineural spread of the tumour. Good cosmetic rehabilitation can be achieved with a facial prosthesis, but most patients still prefer to wear a patch.

References

Goldberg RA, Kim JW, Shorr N . Orbital exenteration: results of an individualized approach. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 19 (3): 229–236.

Frezzotti R, Bonanni R, Nuti A, Polito E . Radical orbital resections. Adv Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 9: 175–192.

Shields JA, Shields CL, Demirci H, Hanovar S, Singh A . Experience with eyelid sparing orbital exenteration: The 2000 Tullos O Coston Lecture. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 17 (5): 355–361.

Ben Simon GJ, Schwartz RM, Douglas R, Fiaschetti D, McCann JD, Goldberg RA . Orbital exenteration: one size does not fit all. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 139: 11–17.

Mohr C, Esser J . Orbital exenteration: surgical and reconstructive strategies. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1997; 235 (5): 288–295.

Gunalp I, Gunduz K, Duruk K . Orbital exenteration: a review of 429 cases. Int Ophthalmol 1995–1996; 19 (3): 177–184.

Rathbun J, Beard C, Quickert MH . Evaluation of 48 cases of orbital exenteration. Am J Ophthalmol 1971; 30: 191–199.

Cook Jr BE, Bartley GB . Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumours in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 746–750.

Wang JK, Liao SL, Jou JR, Lai PC, Kao SCS, Hou PK et al.Malignant eyelid tumours in Taiwan. Eye 2003; 17 (2): 216–220.

Lee SB, Saw SM, Au Eoug KG, Chan TK, Lee HP . Incidence of eyelid cancers in Singapore from 1968–1995. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83 (5): 595–597.

Doxanas MT, Green WR, Iliff CE . Factors in the successful surgical management of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids. Am J Ophthalmol 1981; 91 (6): 726–736.

Doxanas MT, Green WR . Sebaceous gland carcinoma. Review of 40 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 1984; 102 (2): 245–249.

Doxanas MT, Iliff WJ, Iliff NT, Green WR . Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelids. Ophthalmology 1987; 94 (5): 538–541.

de Vries E, van de Poll-Franse LV, Louwman WJ, de Gruijl FR, Coebergh JW . Predictions of skin cancer incidence in the Netherlands up to 2015. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152 (3): 481–488.

Collins GL, Nickoonahand N, Morgan MB . Changing demographics and pathology of non-melanoma skin cancer in the last 30 years. Semin Cutaneous Med Surg 2004; 23 (1): 80–83.

Raasch BA, Buettner PG . Multiple non-melanoma skin cancer in an exposed Australian population. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41 (10): 652–658.

Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D . The Australian Mohs Database: periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (4): 617–623.

Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D . The Australian Mohs Database; Part I: periocular basal cell carcinoma experience over 7 years. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (4): 624–630.

Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle Jr RC, Shields CL . Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (12): 2149–2150.

Payne JW, Duke JR, Butner R, Eifrig DE . Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids. A long-term follow up study. Arch Ophthalmol 1969; 81: 553–558.

Perlman GS, Hornblass A . Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids: a review of patients treated by surgical excision. Ophthal Surg 1976; 7: 23–27.

Howard GR, Nerad JA, Carter KD, Whitaker DC . Clinical characteristics associated with orbital invasion of cutaneous basal cell and squamous cell tumours of the eyelid. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 113: 123–133.

Leibovitch I, McNab A, Sullivan T, Davis G, Selva D . Orbital invasion by periocular basal cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 717–723.

Walling HW, Fosko SW, Geraminejad PA, Whitaker DC, Arpey CJ . Aggressive basal cell carcinoma: presentation, pathogenesis and management. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2004; 23: 389–402.

Savage RC . Orbital exenteration and reconstruction for massive basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma of cutaneous origin. Ann Plast Surg 1983; 10 (6): 458–466.

Chao AN, Shields CL, Krema H, Shields JA . Outcome of patients with periocular sebaceous gland carcinoma with and without intraepithelial invasion. Ophthalmology 2001; 108 (10): 1877–1883.

Niazi ZB, Lamberti BG . Perineural infiltration in basal cell carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg 1993; 46: 156–157.

Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, Lindberg RD, Luna MD . Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg 1984; 148: 542–547.

McNab AA, Francis IC, Benger R, Crompton JL . Perineural spread of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma via the orbit, clinical features and outcome in 21 cases. Ophthalmology 1997; 104 (9): 1457–1462.

Esmaili B, Ahmadi A, Gillenwater AM, Faustina MM, Amato M . The role of supraorbital nerve biopsy in cutaneous malignancies of the periocular region. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 19 (4): 282–286.

Brown CI, Perry AE . Incidence of perineural invasion in histologically aggressive types of basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol 2000; 22: 123–125.

Maroldi R, Farina D, Battaglia G, Maculotti P, Nicolai P, Chiesa A . MR of malignant nasosinusal neoplasms. Frequently asked questions. Eur J Radiol 1997; 24: 181–190.

Williams LS, Mancuso AA, Mendenhall WM . Perineural spread of cutaneous squamous and basal cell carcinoma: CT and MR detection and its impact on patient management and prognosis. Int J Radiol Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 49 (4): 1061–1069.

Tyers AG, Collin JRO . Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery. Butterworth Heinemann, 2nd edn, Oxford, 2001,p 233.

Kennedy RE . Indications and surgical techniques for orbital exenteration. Adv Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 9: 163–173.

Putterman AM . Orbital exenteration with spontaneous granulation. Arch Ophthalmol 1986; 104: 139–140.

Mauriello Jr J, Hank H, Wolfe R . Use of autogenous split thickness dermal graft for reconstruction of the lining of the exenterated orbit. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 100: 465–467.

Menon NG, Girotto JA, Goldberg NH, Silverman RP . Orbital reconstruction after exenteration: use of a transorbital temporal muscle flap. Ann Plast Surg 2003; 50: 38–42.

Wax MK, Burkey BB, Bascom D, Rosenthal EL . The role of free tissue transfer in the reconstruction of massive neglected skin cancers of the head and neck. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003; 5 (6): 479–482.

Chepeha DB, Wang SJ, Marentette LJ, Bradford CR, Boyd CM, Prince ME et al. Restoration of the orbital aesthetic subunit in complex mid facial defects. Laryngoscope 2004; 114 (10): 1706–1713.

Savar DE . High dose radiation to the orbit. A cause of skin graft failure after exenteration. Arch Ophthalmol 1982; 100 (11): 1755–1757.

Wulc AE, Adams JL, Dryden RM . Cerebrospinal fluid leakage complicating orbital exenteration. Arch Ophthalmol 1989; 107 (6): 827–830.

de Conciliis C, Bonavolonta G . Incidence and treatment of dural exposure and CSF leak during orbital exenteration. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1987; 3 (2): 61–64.

Nerad JA, Carter KD, Lavelle WE, Fyler A, Brånemark PI . The osseointegration technique for the rehabilitation of the exenterated orbit. Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109: 1032–1038.

Moran WJ, Toljanic JA, Panje WR . Implant-retained prosthetic rehabilitation of orbital defects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996; 122 (1): 46–50.

Jacobsson M, Tjellström A, Albrektsson T, Thomson P, Turesson I . Integration of titanium implants in irradiated bone: histologic and clinical study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1988; 97: 337–340.

Bartley GB, Garrity JA, Waller RR, Henderson JW, Ilstrup DM . Orbital exenteration at the Mayo Clinic 1967–1986. Ophthalmology 1989; 96 (4): 468–473.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tyers, A. Orbital exenteration for invasive skin tumours. Eye 20, 1165–1170 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702380

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702380

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Subcutaneous pedicled propeller flap for reconstructing the large eyelid defect due to excision of malignancies or trauma

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

A Systematic Review Article on Orbital Exenteration: Indication, Complications and Reconstruction Methods

Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery (2022)

-

Exenteratio orbitae – Indikation, Rekonstruktion und Rehabilitation

Der MKG-Chirurg (2020)