Abstract

Germ-line mutations in the BRCA2 gene are associated with a wide range of cancer types, including the breast, ovary, pancreas, prostate and melanoma. In this study, we evaluated the importance of a family history of stomach cancer in predicting the presence of a BRCA2 mutation in Polish patients with ovarian cancer. A BRCA2 mutation was found in eight of 34 women with ovarian cancer and a family history of stomach cancer versus three of 75 women with ovarian cancer and a family history of ovarian cancer, but not of stomach cancer (odds ratio=7.4; 95% CI 1.8–30; P=0.004). The results of this study suggest that, in the Polish population, the constellation of ovarian and stomach cancer predicts the presence of a germ-line BRCA2 mutation and confirms that stomach cancer is part of the spectrum of BRCA2 mutations. It is expected that the penetrance of BRCA2 mutations for stomach cancer will vary from country to country, reflecting local environmental and lifestyle factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for the majority of families with multiple cases of early-onset breast cancer.1 BRCA2 mutations have also been associated with a range of other malignancies, including cancer of the ovary, prostate, pancreas, melanoma, gallbladder and stomach.2,3 Many of these cancer types appear in males as well as females and it is important that the full spectrum of cancers associated with BRCA2 mutations be understood so that genetic counseling can be optimized to both men and women. This knowledge will help determine which families are candidates for genetic testing and which screening procedures are to be recommended.

We have previously reported that stomach cancer appears in a greater than expected frequency in families in Poland with BRCA2 mutations.4 Although breast cancer is the most common cancer to appear in families with BRCA2 mutations, not all families with BRCA2 mutations contain cases of breast cancer. In the absence of breast cancer, it is often problematic to decide which families should be offered genetic testing. In this report, we estimate the frequency of BRCA2 mutations in a series of ovarian cancer patients who have at least one first- or second-degree relative affected with stomach cancer, and compare this frequency with that for families with ovarian cancer alone.

Material and methods

Families

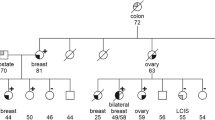

Between 1996 and 2001, 430 consecutive women who were diagnosed with ovarian cancer at either of two hospitals in Szczecin, Poland were invited to participate in this study. This group contained 44 patients with at least one first- or second-degree relative affected by stomach cancer or by ovarian cancer. Families with a history of breast cancer were excluded from this analysis. For each study subject, the ovarian pathology report was reviewed to verify eligibility and to determine the histological type of tumour. We also included 65 patients with ovarian cancer from families of women who were referred to our hereditary cancer clinic and who had a first- or second-degree relative affected with stomach or ovarian cancer. Only one case per family was included. These patients have been referred for counseling and for genetic testing from different regions of Poland because of their family aggregation of cancer.

From each woman with ovarian cancer, a blood sample was obtained for DNA analysis and an extended pedigree was drawn. Information about cancers in relatives was obtained by construction of a pedigree, which contained information on first- and second-degree relatives. Cancers in relatives were based on patient recall and pathological confirmation was generally not available. Cases with mucinous ovarian cancer or borderline tumours were excluded because published evidence does not indicate that BRCA2 mutations underlie these entities.5,6

Mutation analysis

Blood samples were obtained from each study subject for genomic DNA isolation. DNA was isolated using a standard procedure with no modification.7 Mutation analysis of BRCA1 gene for two common Polish mutations (4153delA and 5328insC)8 was carried out by a multiplex specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. The third mutation (C61G)8 generates a novel restriction enzyme site in exon 5. This mutation is detected after digesting amplified DNA with AvaII. To visualize the different BRCA1 alleles, the PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide. Additionally, to evaluate the accuracy of the multiplex technique the results of 30 samples, representing each of the three mutations and normal DNA samples were compared. The results of the multiplex PCR assay and the direct DNA sequencing were 100% concordant. DNA testing results indicating occurrence of mutation were confirmed by sequencing of material from independently taken second blood samples. The entire coding sequence of the BRCA2 gene, including intron/exon splice sites, was amplified in PCR reactions using primers and conditions described previously except for exons 10, 11, 14 and 27 of BRCA2 that were each amplified, as a single fragment, using Expand™Long Template PCR Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). All other exons were amplified using standard PCR conditions and primers (see BCLC, http://www.nhgri.nih.gov/Intramural_research/Lab_transfer/Bic/Member/BRCA2.html). After purification, PCR products were analysed on an ABI 377 DNA Sequencer.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the STATA statistical software package. Fisher's exact test was used for the comparisons of proportions. A level of statistical significance of 0.05 was assumed.

Results

We obtained a blood sample and detailed pedigree information for 34 women with ovarian cancer and a family history of stomach cancer (designated Group A) and for 75 women with ovarian cancer and a family history of ovarian cancer, but not of stomach cancer (Group B). These families are described in Table 1. No case had a first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer (these were excluded previously). In total, 11 BRCA1 and eight BRCA2 mutations were identified among the 34 women who had ovarian cancer and a relative with stomach cancer (Group A) (Table 2). Among the detected changes in BRCA2 there were six mutations causing premature termination of translation (three deletions, one insertion and two substitutions), one substitution causing an in-frame deletion of exon 3 and one missense mutation (Table 3). Four of the alterations resulting in premature termination of translation had not been previously reported to the BIC9 or HGMD (http://uwcmml1s.uwcm.ac.uk/uwcm/mg/search/387848.html) databases. The identified missense variant was localized within a domain of BRCA2 predicted to have functional significance and was not detected in over 100 healthy individuals, suggesting that this change is not a polymorphism. In all, 48 BRCA1 mutations and three BRCA2 mutations were identified among the 75 women with a family history of ovarian cancer, but not of stomach cancer (Table 2). Among the detected changes in BRCA2 there was one deletion, one splice-site substitution causing premature termination of translation and one substitution causing an in-frame deletion of exon 3 of BRCA2 (Table 3).

The combined mutant frequencies for the two groups were similar (55.9% for Group A and 68.0% for Group B) but the presence of stomach cancer was strongly predictive of the presence of a BRCA2 (versus BRCA1) mutation (odds ratio 11.6; 95% CI 2.6–51; P=0.0008). A BRCA2 mutation was found in eight of 34 women with ovarian cancer and family history of stomach cancer versus three of 75 women with ovarian cancer and a family history of ovarian cancer, but not of stomach cancer (odds ratio 7.4; 95% CI: 1.8–30; P=0.004). The characteristics of the families with stomach cancer and BRCA2 mutations are presented in Table 3. Only four of the 11 BRCA2 mutations were in the proposed OCCR.

Discussion

The frequency of BRCA2 mutations differs between countries and is dependent both on the ethnic background of the tested individual and her family history of breast and ovarian cancer.1,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 In Poland, we found that almost 24% of families with at least one case of ovarian cancer and one case of stomach cancer carried a BRCA2 mutation – this frequency is similar to the estimated prevalence of BRCA2 mutations for families with breast–ovarian cancer.1 In contrast, BRCA2 mutations were present in only 4% of families with familial ovarian cancer (without stomach cancer). Although we did not do BRCA2 genotyping on the family members with stomach cancer (most of whom were dead), the magnitude and strength of the observed association (odds ratio=7.385; P=0.0036) supports this relationship. Future studies may include BRCA2 genotyping of a population-based series of stomach cancers and accompanying loss of heterozygosity studies.

The relatively high frequency of BRCA2 mutations in the Polish stomach–ovary families cannot be explained by founder effects as none of the identified BRCA2 mutations is known to be common in the country. Therefore, population surveys of BRCA2 mutations in Poland will be expensive. In other populations, founder mutations in BRCA2 have been observed and facilitate large-scale mutation surveys. The highest frequencies of BRCA2 mutations have been reported in Ashkenazi Jews and in Iceland. A single founder BRCA2 mutation in the Ashkenazi Jewish population (6174delT) occurs with a frequency of about 1.2%17 and is present in approximately 4% of Jewish breast cancer patients,18 in 16% of Jewish ovarian cancer patients,6 and in 6% of Jewish stomach cancer patients.19 In Iceland, 0.4% of individuals carry the 999del5 BRCA2 founder mutation,20 including 8% of breast cancer patients and 8% of ovarian cancer patients.20,21,22 Carriers of the Icelandic 999del5 mutation are susceptible to a range of cancer types.20,23 The risk of stomach cancer was increased in the first- and second-degree relatives of Icelandic carriers of the BRCA2 999del5 mutation (35 observed versus 12.5 expected).23 Differences in the risk of stomach cancer between carriers of BRCA2 mutations in different countries may be explainable by different dietary and lifestyle factors, or might be due to different allelic frequencies of unknown modifying genes.

Studies have suggested that the phenotype in BRCA2 families vary with the location of the BRCA2 gene mutation.24,25 BRCA2 mutations located within the OCCR region (bounded by nucleotides 3035–6629) are associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer than mutations elsewhere in the gene.5,24,25 In this study of ovarian–stomach cancer families, we observed that the detected mutations were not confined to the OCCR. The majority of mutations occurred 5′ of nucleotide 3035 (the 5′ boundary of the OCCR). Future studies are required to establish if there is a region of BRCA2 that is associated with a particularly high risk of stomach cancer.

In summary, our study indicates that the occurrence of both ovarian and stomach cancer in a family is highly predictive of a BRCA2 mutation in Poland. We believe that this data support the recommendation that Polish families at least one case of stomach cancer and one case of ovarian cancer be offered testing for BRCA2 mutations. Owing to the lack of founder mutations in BRCA2, it is premature to recommend BRCA2 mutations to unselected individuals with stomach cancer but further research in this area is needed. Additional studies are also needed to establish if this association is present in other countries.

References

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M et al: Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 676–689.

BCLC – The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium: Cancer risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 1310–1316.

Johannsson O, Loman N, Moller T, Kristoffersson U, Borg A, Olsson H : Incidence of malignant tumours in relatives of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation carriers. Eur J Cancer 1999; 35: 1248–1257.

Jakubowska A, Nej K, Huzarski T, Scott R, Lubiñski J : BRCA2 gene mutations in families with aggregations of breast and stomach cancers. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 888–891.

Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE et al: Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68: 700–710.

Moslehi R, Chu W, Karlan B et al: BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analysis of 208 Ashkenazi Jewish women with ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66: 1259–1272.

Lahiri DK, Schnabel B : DNA isolation by a rapid method from human blood samples: effects of MgCl2, EDTA, storage time, and temperature on DNA yield and quality. Biochem Genet 1993; 31: 321–328.

Gorski B, Byrski T, Huzarski T et al: Founder mutations in the BRCA1 gene in Polish families with breast–ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66: 1963–1968.

Gershoni-Baruch R, Dagan E, Fried G et al: Significantly lower rates of BRCA1/BRCA2 founder mutations in Ashkenazi women with sporadic compared with familial early onset breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36: 983–986.

Foulkes WD, Brunet JS, Warner E et al: The importance of a family history of breast cancer in predicting the presence of a BRCA mutation. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65: 1776–1779.

Loman N, Johannsson O, Kristoffersson U, Olsson H, Borg A : Family history of breast and ovarian cancers and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based series of early onset breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 1215–1223.

Ikeda N, Miyoshi Y, Yoneda K et al: Frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Japanese breast cancer families. Int J Cancer 2001; 91: 83–88.

Vehmanen P, Friedman LS, Eerola H et al: Low proportion of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Finnish breast cancer families: evidence for additional susceptibility genes. Hum Mol Genet 1997; 6: 2309–2315.

Meindl A : German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Comprehensive analysis of 989 patients with breast or ovarian cancer provides BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation profiles and frequencies for the German population. Int J Cancer 2002; 97: 472–480.

Grzybowska E, Zientek H, Jasinska A et al: High frequency of recurrent mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Polish families with breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mutat 2000; 16: 482–490.

van Der Looij M, Wysocka B, Brozek I, Jassem J, Limon J, Olah E : Founder BRCA1 mutations and two novel germline BRCA2 mutations in breast and/or ovarian cancer families from North-Eastern Poland. Hum Mutat 2000; 15: 480–481.

Fodor FH, Weston A, Bleiweiss IJ et al: Frequency and carrier risk associated with common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish breast cancer patients. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63: 45–51.

Warner E, Foulkes W, Goodwin P et al: Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in unselected Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 1241–1247.

Figer A, Irmin L, Geva R et al: The rate of the 6174delT mutation in BRCA2 in patients with non-colonic gastrointestinal tract tumours in Israel. Br J Cancer 2001; 84: 478–481.

Johannesdottir G, Gudmundsson J, Bergthorsson JT et al: High prevalence of the 999del5 mutation in Icelandic breast and ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res 1996; 56: 3663–3665.

Thorlacius S, Struewing JP, Hartge P et al: Population-based study of risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA2 mutation. Lancet 1998; 352: 1337–1339.

Thorlacius S, Sigurdsson S, Bjarnadottir H et al: Study of a single BRCA2 mutation with high carrier frequency in a small population. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 60: 1079–1084.

Tulinius H, Olafsdottir GH, Sigvaldason H et al: The effect of a single BRCA2 mutation on cancer in Iceland. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 457–462.

Thompson D, Easton D : Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68: 410–419.

Gayther SA, Mangion J, Russell P et al: Variation of risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with different germline mutations of the BRCA2 gene. Nat Genet 1997; 15: 103–105.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jakubowska, A., Scott, R., Menkiszak, J. et al. A high frequency of BRCA2 gene mutations in Polish families with ovarian and stomach cancer. Eur J Hum Genet 11, 955–958 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201064

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201064

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and the risk of bladder or kidney cancer in Poland

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2022)

-

Double germline mutations in APC and BRCA2 in an individual with a pancreatic tumor

Familial Cancer (2017)

-

BRCA1 founder mutations do not contribute to increased risk of gastric cancer in the Polish population

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2016)

-

The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in prostate, pancreatic and stomach cancers

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2015)

-

Incidence of colorectal cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from a follow-up study

British Journal of Cancer (2014)