Key Points

-

Encourages the reader to consider professional messages surrounding the management of concerns relating to a colleagues performance or conduct.

-

Challenges current professional philosophies surrounding criticising colleagues.

-

Invites the reader to consider the consequences to the profession's reputation should the duty to raise concerns not be engaged with.

Abstract

Background The ability of the dental profession to self-regulate and address poor performance or impairment is crucial if practitioners are to demonstrate a public commitment to patient safety. Failure of the profession to actively engage in this activity is likely to call into question trustworthiness and ability to place the interests of patients and the public first.

Aim To investigate attitudes towards self-regulation and the raising of concerns as expressed through the ethical codes of different dental professional and regulatory organisations.

Method A qualitative review of professional codes of ethics written and published by dental associations and regulatory bodies using thematic analysis to discern common attitudes and perspectives on self-regulation.

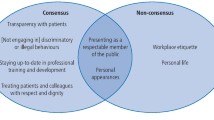

Results Four main themes were identified; (1) explicit expression of the need to report; (2) warning against frivolous reporting; (3) acceptance of reporting being difficult and; (4) threshold requiring a professional to report. From these themes, common and differing attitudes were then explored.

Conclusions This review shows that often codes of ethics and practice do discuss an obligation to self-regulate and raise concerns but that this is accompanied by an anxiety surrounding unsubstantiated or malicious reporting. This gives the collective guidance a defensive tone and message that may be unhelpful in promoting a culture of openness and candour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Society relies upon the dental profession to self-regulate.1 Self-regulation has traditionally been a professionally-led activity, but has been steadily eroded by a variety of societal and professional factors. One such contributor is a perception that the healthcare professions will close ranks in the face of concerns about colleagues' health, competency or conduct.2 This qualitative review will examine codes from several jurisdictions in order to carry out a thematic analysis to allow investigation of attitudes relating to self-regulation in dentistry.

Self-regulation is sometimes given to represent more than the raising of concerns or reporting in a professional context. As will be explored, this is a view not shared by many of the codes examined. Therefore, self-regulation in the context of this article refers to the action of intra-professional reporting and the management of concerns relating to the conduct, competence or health of professional colleagues. Through the findings of this review, it will be ascertained whether the attitudes of professional associations that are displayed by their codes are congruent with the concept of self-regulation and the duty to place the interests of patients before the protection of professional interests. Some believe that dental professionals will always struggle to place a duty to patients above a tendency toward self-interest.3 It is the aim of this review to investigate whether the attitudes demonstrated within codes of ethics give merit to this concern.

Methodology

The objective of this review was to identify relevant ethical codes of dental associations and regulators to allow a qualitative review of the attitudes and key themes relating to self-regulation to be drawn out and discussed. Thematic analysis is defined to be, 'a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data.'4 These identified patterns and emerging themes then become the categories that provide a framework for further analysis and comparison of the data.5 Thematic analysis was chosen as a qualitative method to analyse codes of ethics and conduct to allow a rich and detailed exploration of attitudes conveyed by regulatory and professional codes.

Key codes of ethics were identified from searching the websites, in August 2017, of dental associations from across jurisdictions. Where codes of conduct did not exist from professional associations, the code of conduct from the regulator of that jurisdiction was instead used. It was felt that this was valid as in many cases, professional associations defer to the guidance set out in legislation or by regulatory bodies rather than having their own code of practice or conduct. Two examples where this is explicitly the case would be South Africa and Ireland where the code of conduct of the Health Professionals Council of South Africa and the Dental Council of Ireland are used respectively. Where a professional association's code of conduct exists, but is not publicly available, that jurisdiction was excluded from the review. This choice to exclude non-publicly available codes was made in recognition of the fact that codes of ethics and practice should be available for the public to see the dental profession's commitment to ethical practice and, in specific relevance to this research, self-regulation. If these are not publicly available their ability to demonstrate this is negated and so the code from that jurisdiction was excluded. In Canada, many of the provincial regulators and professional associations are the same body. Where associations had different codes of conduct at local (state, province or territory) and federal level (such as the Australian Dental Association Inc.) the federal code was preferred. This is because the federal code often acts as the progenitor to local codes. This process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Inclusion criteria for guidance to be included in this study were: 1) guidance produced by a dental association or regulator; 2) guidance from associations that cover multiple jurisdictions; 3) guidance from associations that have both federal and local (state or provincial) sections, and 4) guidance and standards set by dental regulators within jurisdictions where the professional associations defer to this or do not have codes of their own. Jurisdictions and codes were excluded where: 1) the guidance was not in English or that has not been translated on the authority of the issuing association, and 2) if the association of that jurisdiction did not make its code of ethics publicly available.

Results

Using the criteria for inclusion and exclusion, codes of ethics and practice were found from 15 different dental regulators and professional associations; the World Dental Federation (FDI),6 the Council of European Dentists,7 the General Dental Council (UK),8 the Dental Council of Ireland,9 the Australian Dental Association,10 the American Dental Association,11 the Indian Dental Association,12 the Health Professionals Council of South Africa,13 the Alberta Dental Association and College,14 the Manitoba Dental Association,15 the Newfoundland and Labrador Dental Board,16 the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario,17 the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties,18 the Malaysian Dental Council19 and the Singapore Dental Council.20 These are displayed in Table 1. It was identified that the New Zealand Dental Association and the Hong Kong Dental Association had codes of ethics/conduct, but these were not publicly available.

Themes

The following themes were identified within the guidance as a collective, by careful reading and re-reading of the portions of the guidance relevant to self-regulation and raising concerns. The contribution of each piece of guidance to each theme will be discussed and reported. The themes identified were:

-

Explicit expression of the need to report

-

Warning against frivolous reporting

-

Acceptance of reporting being difficult

-

Threshold requiring a professional to report.

Explicit expression of the need to report

The first theme examines whether the codes acknowledge that the dental profession has a need to engage in self-regulation and that this is part of the profession's duty in protecting the public.

The ethical and professional requirement for self-regulation is strongly recognised and affirmed by the FDI: 'The main requirement for self-regulation, however, is wholehearted support by dentists for its principles and their willingness to recognise and deal with unsafe and unethical practices.'6 As well as a recognition of the importance of raising concerns, the FDI states that dentists are; 'often the only ones who recognise incompetence, impairment or misconduct.'6 Similar duties to engage in self-regulation are affirmed by both the American and the Indian Dental Associations who both state that dentists are obliged to report 'gross or continually faulty treatment by other dentists.' Several codes recognise that self-regulation is a privilege given to the dental profession by society, rather than an automatic right (Manitoba Dental Association, Alberta Dental Association and College, Newfoundland and Labrador Dental Board).Within these codes, there is a strong obligation to promote public trust in the profession. The codes state that the overwhelming purpose of self-regulation is the protection of the public. This duty is not conditional upon situations where professionals have positions of responsibility. The Malaysian Dental Council states that: 'Practitioners may bring to the attention of the Council, any action on the part of any practitioner which, in his opinion, potentially may undermine the honour of the profession.'19 There is no explicit requirement to report demonstrated within this guidance and is likely to be interpreted that the use of the word 'may' indicates a voluntary nature with regard to reporting. The Council goes on to state: 'When a dental practitioner comes across treatment which in his opinion is so unsatisfactory that it must be carried out again he has an obligation, both legal and ethical, to so inform the patient.' Later in the guidance it is stated: 'When a dental practitioner becomes aware of a colleague's incompetence to practice...then it is ethical for the practitioner to draw this to the attention of the Council.' Collectively, this supports the interpretation that reporting to the Council is not a professional requirement. Interestingly however, the Malaysian code is the only one to specifically require the reporting of concerns relating to inadequate treatment to a patient. The Singapore Dental Council states: 'The purposeful concealment of the truth about any aspects of [a] patient's state of oral health, treatment or standard of work done may be construed as dishonesty.'20 There is no discussion of an explicit need to report to the Council, concerns relating to a fellow practitioner.

The General Dental Council (UK) regulates all dental professionals and within the code, reference is made to those registrants who may have limited control of their environments stating that these professionals are equally responsible for raising concerns. The code also discusses that the requirement to raise concerns 'overrides any personal and professional loyalties or concerns you might have (for example, seeming disloyal or being treated differently by your colleagues or managers).'8 It is the only code to overtly state that professional duty has priority over personal relationships.

Concerns may not be about another professional; some of the codes (Health Professionals Council of South Africa and General Dental Council [UK]) discuss the need for dental professionals to be responsible for their own health and performance, placing a duty on those who may develop impairments to refer themselves to the regulator. The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties Code of Ethics makes reference to a need to report impairment, but makes no mention of reporting competency-related concerns. The wording is also of note in this guidance with regards to the duty to report; the word 'should' is used rather than 'must' which is often used in other guidance to demonstrate the differing levels of ethical obligation.21 This might suggest that the reporting of concerns in this jurisdiction is classed to be an ideal rather than a concrete aspect of professional obligation.

Warning against frivolous reporting

A key feature of many of the codes is a warning to potential reporters that concerns must not be unsubstantiated. There is a delicate balance between encouraging professionals to speak out about poor or dangerous practice and discouraging frivolous or vindictive reporting. This theme examines the tone and attitude taken in the guidance of how this balance is addressed.

The collective guidance tends to take an immediately suspicious approach as to the motivations of dental professionals in reporting. Jealousy (FDI) and the opportunity to malign a colleague (Indian Dental Association) are given as potential motivations as to why dentists might report. Many of the codes warn against unjustified reporting, stating that those who report frivolously may encounter hostility or ill will, and be subject to disciplinary proceedings (Indian and American Dental Associations). Statements within the codes that highlight the negative and unjustified reasons why dentists might raise concerns, risk tarnishing all those who make notifications as having these negative motivations. The FDI code recognises that hostility will likely be encountered by both justified and non-justified reporters. With the majority having established a duty to inform, a common statement within the codes is that this should be done without disparaging comment being made about past treatment (American Dental Association and Council of European Dentists). In the case of the Council of European Dentists, this is the only mention of self-regulation that is made within the code. The General Dental Council (UK) states; 'You must not make disparaging remarks about another member of the dental team in front of patients. Any concerns you may have about a colleague should be raised through the proper channels.'8 The Malaysian Dental Council also refers to disparaging remarks relating to colleagues. Immediately after asserting the ethical and legal requirement to inform patients about inadequate treatment, it is stated: 'However, a dental practitioner should not refer disparagingly, orally or in writing, to the service of another practitioner to the patient or a member of the public.'19 The Malaysian Dental Council also states that positive comments should be made to patients, dentists should 'speak out in recognition of good work.' The Singapore Dental Council states: 'A dentist shall refrain from making gratuitous and unsustainable comments which, whether expressly or by implication, set out to undermine the trust in a professional colleague's knowledge or skills.'20

Language choice is also of note within the codes; the Australian code discusses calling into question another dental professional's integrity. Integrity does not necessarily have anything to do with competence or impairment. While a lack of integrity may reflect issues with conduct, the use of the term in the guidance has the potential effect that the issue of raising concerns is not discussed. Integrity as a concept may refer to adherence to codes of practice or organisation rules rather than making any comment about personal morality.22 The South African Health Professions Council guidance, in recognising an obligation to report, states; 'A practitioner shall not cast reflections on the probity, professional reputation or skill of another person registered under the Act or any other Health Act.' (Section 12)13 If one cannot cast reflections on the probity, reputation of skill of a colleague then it is very likely that one cannot report to patients where there are concerns, but is also likely to discourage reports to the regulator. The Saudi Code states that comments that are critical of colleagues should be made in professional arenas, away from patients.

The Saudi code is measurably different to the other codes discussed as it has strong and overt religious influence. Therefore, many Islamic ethical ideals are tied into considerations when dictating how healthcare practitioners should act. Other phrases that are used when discussing behaviours practitioners should avoid are 'back-biting' and 'tale-bearing'.18 Elsewhere in the guidance, it is stated that within the Quran, back-biting is relative to the eating of a person's flesh and is regarded, therefore, as a serious transgression.23

Many of the codes discuss the need to consult with the previous treating dentist(s) as part of the decision-making process before concerns are reported to patients or to the regulator (American Dental Association, the FDI, the Manitoba Dental Association and the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario). The discussion of concerns about a colleague with this same individual seems problematic. Approaching a colleague in this way potentially places a practitioner in the role that should be occupied by the regulator and with an assumed authority to act in this way (that is, to decide whether to escalate or not). The danger that a dental professional might be encouraged to act in this way is of concern due to the likelihood that upon investigation, hostility is encountered and the option of inaction is the easiest and most palatable solution. The codes of practice are generally poor at recognising a need for patient consent before discussing treatment issues with a previous dentist with only two codes referencing a need to comply with relevant privacy legislation (American Dental Association and the Manitoba Dental Association).

Acceptance of reporting being difficult

Reporting about colleagues is difficult even when concerns are strongly held. This theme was identified as existing in only a minority of the codes. Codes that did not acknowledge that reporting is difficult were not facilitating professional engagement in self-regulation as much as they could. Those who potentially wish to raise concerns need to be supported in doing so; a lack of acceptance of this fact is likely to dissuade those who might be uncertain.

The FDI and American Dental Association codes of ethics make reference to the fact that reporting is likely to be a difficult task. The FDI states; 'The application of this principle is seldom easy' and 'A dentist may also be reluctant to report a colleague's misbehaviour because of friendship or sympathy (“there but for the grace of God go I”). The consequences of such reporting can be very detrimental to the one who reports, including almost certain hostility on the part of the accused and possibly other colleagues as well.'6 The FDI's commentary that a dental professional might consider not reporting due to personal relationships gives credence to the accusation that the dental profession is not able to put the interests of patients before concepts of collegiality. The Singapore Dental Council does not reference that the reporting of colleagues is difficult, but does reference that disclosure of negative outcomes to patients is likely to be; 'Although it may not be beneficial to always inform the patient of every complication that has occurred, honesty is at most times the best policy.'20

The American Dental Association also acknowledges that there may be difficulty in reporting, but more from a decision-making process than the management of the emotional aspects of reporting against a colleague. 'There will necessarily be cases where it will be difficult to determine whether the comments made are justifiable. Therefore, this section is phrased to address the discretion of dentists and advises against unknowing or unjustifiable disparaging statements against another dentist.'11 While the General Dental Council (UK) does not make any frank statement about reporting being difficult, the code acknowledges that the matter is not straightforward and that concerns are likely to cause a professional to feel conflicted. There is interaction between this theme and that of the threshold requiring a professional to report in the case of the General Dental Council (UK) as will be discussed below.

Threshold requiring a professional to report

When are concerns justified and what level of deviation from accepted conduct or competency needs to be seen before a concern might be raised? This theme explores the threshold in the codes, both individually and as a collective set, that must be overcome before concerns should be raised.

The FDI states that practices that are 'unsafe or unethical' should be reported. The American Dental Association (and both the Indian Dental Association and Malaysian Dental Council) refer to 'instances of gross or continual faulty treatment by other dentists' as the threshold for reporting to be obligated. Other associations and regulators talk of reasonable concerns. Some of the codes talk about informing patients of their oral health condition in a non-subjective fashion (Dental Council of Ireland, Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario, Manitoba Dental Association). The Manitoba Dental Association states that before comments might be made to patients, dentists must be fully informed about past treatment. The use of the word fully sets the threshold to raise concerns at a very high level.

The code of the General Dental Council (UK) sets a comparatively low threshold for potential reporters. The guidance also states that concerns do not need to be proved in order to justify them being investigated and where doubt exists, concerns must be raised. This would seem to contradict the guidance from other codes that state that a high threshold should be overcome before concerns are reported. This is significant; it recognises that those with concerns are likely to have doubts, regardless of the strength of their concern.

Discussion

Much of the guidance references that the making of disparaging or derogatory comments about the competency of one's colleagues is not acceptable. The scope of such directives is unclear, it is difficult to determine whether notifying a patient that treatment they have had has been harmful or non-therapeutic would be construed as being against many of the codes of conduct explored in this review. Criticism of a colleague that is justifiable might still be classed to be disparaging or derogatory, regardless of how such comments are made. Many of the statements made within the codes that prohibit criticism of colleagues may only apply to non-justified criticism but this is open to interpretation. This review has shown that whatever each authority might have independently intended from their code of ethics, the result is one where no distinction seems to be made between frivolous and meritorious reporting and criticism.

Many of the codes acknowledge that patients have a right to know the status of their oral health. This right of knowledge is then contradicted by codes that state that only objective disclosures may be made to patients and that comments that could be construed to be derogatory should not be made. A proposed measure of dishonesty is to examine the intentions of someone giving a half-truth.24 In the case where a dental professional only gives an objective explanation to a patient with the intention of not calling into question the practice of a colleague, on the basis of the intention, this would be considered to be morally equivalent to lying.25 The phrasing of the Australian Dental Association code might suggest that information relating to the patient's oral condition, in the context of past treatment, should not be given spontaneously, with the patient needing to specifically request an opinion. Often, dental professionals are encouraged to only be objective and factual with patients in describing present oral condition or issues with past work. This neglects to consider that subjective values play a large part within dental practice; dental professionals cannot purely live within clinical facts. Where a patient is given only clinical information, with no subjective interpretation, this may only be part of the picture for the patient; the practitioner's own justified concerns not being communicated. From an ethical and moral perspective, this would be tantamount to sophistry. The line between justified and unjustified criticism is thin and frequently blurred. Because of this, as well as the fear of incurring the wrath of one's own colleagues, the culture of not informing patients of one's concerns that something might not be right may be perpetuated.

Often, the codes do not make a distinction between the concept of raising concerns to the regulator and the discussion of concerns with patients in a clear manner. Some codes state that only factual information may be given to patients, others state that disparaging comments may not be made, but a deeper meaning of this term and the other synonyms used is not explored. Patients have a right to know whether treatment has had no therapeutic benefit.26 Dentistry as a profession is not objective; in much of its domain it is value-laden27 and therefore to attempt to restrict this nature when addressing concerns seems to sway towards a protectionist slant. Even the codes themselves, in discussing what constitutes a threshold to report, are not objective. Within the guidance, the issue of raising concerns to the regulator and raising concerns to patients are treated as a dichotomy. In the eyes of the guidance, patients are not entitled to the same information about concerns that a regulator might be. In several common law jurisdictions, the standard in respect of how much information patients should be given has moved away from the reasonable professional standard to the standard of a reasonable patient.28,29 It does not seem to be congruent with this change for codes of ethics to state that patients should not be informed should there be concerns surrounding treatment received. A common defence to non-disclosure is the concern that not all patients will want to know the full truth of their situation. This seems to be a confusing approach; to protect those who might not want to know, no one must know. It should be the patient who decides whether they want access to an explanation of their oral health and treatment history, not the treating clinician.30 Dental professionals should find moral courage in the findings of research by Chambers.31 In a study examining patient and professional attitudes towards justifiable criticism, patients significantly favoured reporting of concerns to a regulator than the surveyed dentists. When clinicians report, they may not find themselves championed by all colleagues, but it is clearly what patients expect of their professionals.

In the Australian case of Dean v Phung,32 a dentist carried out root fillings and placed crowns on the entirety of a patient's dentition due to the patient having suffered minor, uncomplicated trauma to his maxillary central incisors at work. The treatment was found to have been unnecessary as well as having been negligently executed in a judgement handed down by the New South Wales Court of Appeal. If a recipient of such grossly inappropriate or inadequate treatment were to visit another dental professional either during or after such work, regardless of jurisdiction, it would seem to be against the public interest for that professional not to be able to raise concerns to a patient based on the justification that this is unfair to a colleague. Thankfully, such instances of grossly poor practice are not frequent, but the codes discuss absolutes. The language of the codes in this matter is important; the American (and Indian) Codes state that 'instances of gross or continual faulty treatment by other dentists' should be reported. Welie criticises the American code for this language; he states that it would imply that occasional and moderately faulty work is therefore acceptable.1 There would appear to be such a fear of unjustified criticism that the possibility of any criticism is discouraged. While a simple examination will never illicit the entire facts of a clinical situation, the approach of inaction based upon hope that there might somehow be an innocent explanation of concerns must be avoided. It is an approach that has led to major scandals within the field of health and social care.33 In Australia, legislation34 requires that where concerns arise relating to the standard of a colleague's practice, the dental practitioner forming the belief must report this. The threshold set by the legislation is a 'reasonable belief'35 – there is no requirement to know the full facts of the case. It seems to be contrived to suggest that in such circumstances a practitioner should not comment upon concerns to the patient, instead leaving this role to the regulator to potentially disclose at a later date. Whatever worries exist about damage to the profession's reputation, these should not override the patient's basic right to know what has been done to them by that same profession.

The UK has recognised the need for a 'Duty of Candour' within healthcare36 with this being provided for by legislative instrument,37 and while the General Dental Council's code was produced before the Francis Report, the guidance is certainly in line with practitioners being open and honest with patients. It achieves this by requiring registrants put patients' interests first, to be honest and act with integrity and to offer an apology and a practical solution if a patient makes a complaint. In 2016, the General Dental Council (UK) released a joint statement on the Duty of Candour along with the other UK healthcare regulators. In relation to when treatment goes wrong, the guidance states: 'When something goes wrong with a patient's care, you must: tell the patient; apologise; offer an appropriate remedy or support to put matters right (if possible); and explain fully the short and long term effects of what has happened.'38 While the guidance would seem to relate more towards a practitioner's own conduct and standard of care, the legislative instrument does not share this focus and applies to all practitioners involved in a regulated health activity. Given this universality given by the instrument, the intention of the General Dental Council (UK) is that the Duty of Candour extends to all aspects of a patient's care; raising concerns about previous care is an important duty within this.

Limitations

One of the challenges encountered was how a sample of professional associations and regulatory bodies might be gathered. This research relied upon the use of the Internet to locate relevant organisations and documents. One issue with this is that it potentially eliminates the inclusion of organisations that do not have a website (such as the Papua New Guinea Dental Association). These organisations are more likely to be from developing nations; it is evident that this category of jurisdictions was underrepresented within this study's sample. Professional bodies are not necessarily easily identified and within some areas, multiple organisations exist. It is difficult to justify the inclusion of one professional association over another. This issue was not identified to be a barrier within this study due to the jurisdictions where multiple professional associations existed were predominantly non-English speaking as their first language.

Despite the exclusion of non-English-written guidance and the non-intentional exclusion of organisations without a website, our results are generalisable to the population of professional organisations and regulatory bodies. The collection of 15 documents analysed from different professional and regulatory organisations across a breadth of jurisdictions, demonstrates a wide range of guidance and standards from a significant range of cultures.

Conclusion

Most modern ethical codes within healthcare may trace their roots back to the American Medical Association's inaugural code of ethics in 1847.39,40 This common origin can be observed within many of the dental codes. This has led to common perspectives, use of terminologies and deficiencies. The desire to prevent and restrict malicious or unfounded criticism is understandable. It is potentially for this reason that codes of ethics and conduct are often worded in a manner that could prohibit reporting by the setting of a high threshold. Thresholds might be set higher through choice of language or through requirements of a high degree of factual certainty. While it is possible to empathise with the anxiety of professional bodies regarding the raising of concerns, moderation cannot occur at the expense of society by preventing disclosure, the restriction of which raises serious ethical concerns. Through the profession acting in this manner, there is a danger that self-regulation might be rendered impotent. Because of an approach that seeks to treat all situations as equal, much of the guidance falls victim to appearing to be biased towards the protection of the dental profession. Most professional codes of ethics have been written by members of that representative profession. Codes that have input from non-professional expertise may have a stronger focus towards community-orientated principles rather than solely professional values.41

The FDI ethics manual states that traditionally dentistry has taken pride in its status as a self-regulating profession; although it goes on to admit that self-regulation has sometimes failed. Some might debate that the status of dentistry as a self-regulating profession has been eroded since the publication of the UK Government White paper which criticised the health professions for a lack of engagement in self-regulation.42 It is immaterial as to whether one chooses to classify dentistry as being self-regulating or not; there is still a requirement for dental registrants to safeguard the integrity of the profession. Regardless of the structure of regulation, dental professionals remain the best placed group to recognise and raise concerns, should they arise, relating to colleagues.

This is the first instance of thematic analysis being used to analyse codes of conduct within dentistry. The results of this review have shown that most of the professional and regulatory codes that have been explored recognise a professional duty to raise concerns. However, this duty is attenuated by failure to demonstrate meaningful support for those with concerns; many codes instead focus upon warning against frivolous reporting and unfounded criticism to patients. Self-regulation, by definition, must be led by the profession. If there is reluctance to engage in this, then it is likely that trust in the dental profession to place society's interests first will be seriously inhibited. The attitudes that this review has explored would suggest that in many, but not all cases, hesitance exists within the dental profession towards the appropriate practice of self-regulation.

References

Welie J V . Is dentistry a profession? Part 3: Future challenges. J Can Dent Assoc 2004; 70: 675–678.

Parker M . Embracing the new professionalism: Self-regulation, Mandatory notification and their discontents. J Law Med 2011; 18: 456–466.

Bertolami C . Why our ethics curricula don't work. J Dent Educ 2004; 68: 414–425.

Braun V, Clarke V . Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych 2006; 3: 77–101.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T . Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013; 15: 398–405.

World Dental Federation (FDI). FDI World Dental Federation Dental Ethics Manual. 2007.

Council of European Dentists. Code of Ethics for Dentists in the European Union. 2007.

General Dental Council (UK). Standards for the Dental Team. 2013.

Dental Council of Ireland. Code of Practice relating to: Professional Behaviour and Ethical Conduct. 2012.

Australian Dental Association. Policy Statement 6.5.1: Code of Ethics for Dentists. 2012.

American Dental Association. Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct. 2012.

Indian Dental Association. Code of Ethics. Undated.

Healthcare Practitioners Council of South Africa. Ethical Rules of Conduct for Practitioners Registered Under the Health Professions Act 1974–2006.

Alberta Dental Association and College. Code of Ethics. 2007.

Manitoba Dental Association. Code of Ethics. 2002.

Newfoundland and Labrador Dental Board. Code of Ethics. Undated.

The Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. By-laws of The Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. 2016.

Saudi Commission for Health Specialities. Code of Ethics for Healthcare Practitioners. 2014.

Malaysian Dental Council, Code of Professional Conduct. 2008.

Singapore Dental Council, Ethical Codes & Guidelines. 2006.

Brotherton S, Kao A, Crigger B J . Professing the values of medicine: The Modernized AMA Code of Medical Ethics. JAMA 2016; 316: 1041–1042.

Banks S . Integrity in professional life: Issues of conduct, commitment and capacity. Br J Social Work 2010; 40: 2168–2184.

The Holy Quran, Al Hujurat 49: 12.

Bok S . Lying: moral choice in public and private life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Cox C L, Fritz Z . Should non-disclosures be considered as morally equivalent to lies within the doctor–patient relationship? Journal of Medical Ethics 2016; 42: 632–635.

Corless-Smith D . Whistle-blowing and professionalism in dentistry. Clinical Risk 2006; 12: 44–48.

Nolan P W, Smith J . Ethical awareness among first-year medical, dental and nursing-students. Int J Nurs Stud 1995; 32: 506–517.

Rogers v Whitaker [1992] HCA 58; 175 CLR 479.

Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11.

Kirklin D . Truth telling, autonomy and the role of metaphor. J Med Ethics 2007; 33: 11–14.

Chambers D W . What do dentists do when they recognize faulty treatment? To tattle or build a moral community? JACD 2017; 84: 4–8.

Dean v Phung [2012] NSWCA 223.

Ashley L, Armitage G, Taylor J . Recognizing and referring children exposed to domestic abuse: a multi-professional, proactive systems-based evaluation using a modified Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA). Health and Social Care in the Community 2017; 25: 690–699.

The National Law as applies in each Australian State or Territory; Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2010 (Australian Capital Territory); Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2010 (New South Wales); Health Practitioner Regulation (National Uniform Legislation) Act; Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (South Australia) Act 2010; Health Practitioner National Law (Tasmania) Act 2010; Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Victoria) Act 2009; Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Western Australia) Act 2010.

Section 141 of each Australian state's or territory's version of the National Law.

Francis R . Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. 2013.

Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014, Regulation 20.

General Dental Council (UK). Being open and honest with patients when something goes wrong: The professional duty of candour. 2016.

American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics. 1847. Available at http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/sites/default/files/Americaan%20Medical%20Association%20Code%20of%20Medical%20Ethics%20%281847%29.pde (accessed February 2018).

Veatch RM . Hippocratic, Religious, and secular medical ethics: the points of conflict. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2012.

Deans Z, Dawson A . Why the Royal Pharmaceutical Society's Code of Ethics is due for review. Pharm J 2005; 275: 445–446.

Department of Health. Trust, assurance and safety: the regulation of health professionals in the 21st century. London: DH, 2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holden, A. What do dental codes of ethics and conduct suggest about attitudes to raising concerns and self-regulation?. Br Dent J 224, 261–267 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.125

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.125

This article is cited by

-

Exploring how newly qualified dentists perceive certain legal and ethical issues in view of the GDC standards

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Exploring the evolution of a dental code of ethics: a critical discourse analysis

BMC Medical Ethics (2020)