Abstract

The relationship of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) to antidepressant response was examined in 95 elderly patients receiving a protocolized treatment for depression with paroxetine or nortriptyline. Patients were treated for up to 12 weeks and assessed weekly with clinical ratings and measurements of plasma drug concentrations. Twenty-one of the paroxetine-treated subjects were found to have the ll genotype and 30 had at least one s allele. There were no baseline differences between these groups in pretreatment Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) scores or anxiety symptoms. During acute treatment with paroxetine, mean reductions from baseline in HRSD were significantly more rapid for patients with the ll genotype than for those possessing an s allele, despite equivalent paroxetine concentrations. Onset of response to nortriptyline was not affected. Allelic variation of 5-HTTLPR may contribute to the variable initial response of patients treated with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Variability in response to antidepressant treatment may be dependent on interindividual differences in drug concentration or drug targets. The serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) promoter region (5-HTTLPR) insertion/deletion polymorphism is known to affect transporter expression and function (Lesch et al. 1996). A long (l, 528 bp) and a short (s, 484 bp) form affect the expression and function of the serotonin transporter. Those with the s variant, approximately 42% of Caucasians, have reduced transcription of the 5-HTT gene promoter, resulting in decreased 5-HTT expression and an approximate 50% reduction in serotonin uptake (Heils et al. 1996; Collier et al. 1996). We hypothesized that the initial pharmacologic impact of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was likely to be proportionately greater for those patients with enhanced serotonin reuptake (i.e., those possessing the ll genotype). These patients would thus be expected to respond earlier to an SSRI than those with one or two copies of the dominant s allele. Because inhibition of serotonin reuptake by a SSRI is believed to be only the initial step in a complex adaptive process, we further hypothesized that final outcome, for those receiving paroxetine, would not differ between the transporter promoter genotypes and that the acute response of patients treated with nortriptyline, an antidepressant affecting predominately reuptake of norepinephrine, would not be affected by this polymorphism.

METHODS

This study was conducted in the geriatric inpatient units and the outpatient Late Life Depression Clinic of Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic as previously described (Mulsant et al. 1999). Study participants were evaluated with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders (SCID-IV; First et al. 1997) and several rating scales, including the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton 1967) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al. 1975). Written informed consent was obtained from each subject after the procedures had been fully explained.

For inclusion in the study, patients had to meet the following criteria: age 60 years or older; DSM-IV major depressive episode with neither psychotic features nor history of bipolar or schizoaffective disorder; baseline HRSD score of 15 or above; MMSE score of 18 or above; no history of alcohol or other substance abuse or dependency during at least the past year; and no specific medical condition contraindicating treatment with either nortriptyline or paroxetine (e.g., QRS longer than 120 ms or bradychardia with heart rate below 50). Ninety-six subjects (mean age: 72.0 ± 7.9 years) were randomized under double-blind conditions to treatment with either nortriptyline (n = 45) or paroxetine (n = 51) after a washout of all psychotropic medications except for lorazepam. Patients received initial doses of 25 mg of nortriptyline, or 20 mg of paroxetine. Nortriptyline doses were adjusted weekly until the plasma level was between 50 and 150 ng/ml. Paroxetine doses were increased to 30 mg after 5 weeks in patients who still had an HRSD score of 15 or above or who had experienced a decrease in HRSD score of less than 50%.

Plasma was obtained weekly for measurement of paroxetine and nortriptyline concentrations. Antidepressant drug and metabolite concentrations were measured by high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection according to methods previously described (Pollock et al. 1992; Foglia et al. 1997).

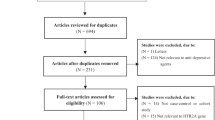

Lymphocytes were harvested from whole blood and DNA was extracted from lymphocytes using a QIAamp DNA blood kit (Qiagen Inc.). S and l alleles were determined using DNA amplification (PCR) and established flanking primers. Amplification products were resolved by electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide staining and UV transillumination, according to Edenberg and Reynolds (1998). Samples from 96 subjects were analyzed for 5-HTT-promoter polymorphism. Mixed effects repeated measures ANOVA based upon observed HRSD scores was utilized to test effects of genotype group, time and group by time interaction in each treatment group. The predicted scores from these models were then used to compute the decrease in Hamilton scores. This intent-to-treat approach allowed all subjects’ data to be included even if they terminated early.

RESULTS

Thirty-four (67%) of the paroxetine-treated and 23 (52%) of the nortriptyline-treated subjects completed the acute trial. Of the 96 subjects genotyped, 35 subjects were ll genotype, 40 were sl and 20 were ss. One subject had a rare allele, xl and was not included in any analyses. Because the s allele is functionally dominant (Lesch et al. 1996; Collier et al. 1996) genotypes were classified into two groups: those with the ll and s (sl and ss alleles). There were no differences between groups in age, gender, race, age of first depression, severity of anxiety symptoms, or cognitive status. For patients treated with paroxetine, there was a significant time effect (weeks; F12,446 = 74.73, p < 0.0001) as well as a group (s vs. ll) by time interaction (F12,446 = 1.95, p = 0.0275), with the s group taking longer to improve than the ll (see Figure 1). For those treated with nortriptyline, there was only an effect of time (F12,348 = 53.49, p < 0.0001). At the second week of paroxetine treatment, 11 (52%) of the ll group had a 50% reduction in Hamilton score compared to none (n = 30) of the s group (χ2 = 20.04, p < 0.0001) and the mean percentage decline in HRDS scores from baseline values at this time was 49.3 ± 10% for the ll group as compared to 29.6 ± 5% for those with one or two s alleles. In contrast, for nortripyline treated patients, only 2 (14%) of the homozygous ll group and 5 (17%) of the s group had a 50% reduction in HRSD scores at week two.

No significant differences between the s and ll groups in the mean weekly paroxetine or nortriptyline plasma levels were found. At the conclusion of the study (12 weeks), there were no differences between ll and s groups in the number of responders (HRSD ⩽ 10) for either medication.

DISCUSSION

Allelic variation in 5-HTTLPR may contribute to the variable initial response of older patients treated with an SSRI. Those with ll genotype appear to respond more rapidly to an SSRI (paroxetine) than those with one or two copies of the s allele. By contrast, the onset of therapeutic response to the noradrenergic antidepressant nortriptyline was not influenced by the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism. Our findings are consistent with a prior report that examined the relationship of variation in the transporter promoter and response to an SSRI. In that study, Smeraldi and associates (1998) found that psychotic depression was less responsive to fluvoxamine in those with ss genotype. It should also be noted that Young and colleagues (1999) recently reported a significantly better antidepressant response in the homozygous ll patients who were treated with nortriptyline. Contrary to the implications of Lesch et al. (1996) but consistent with Serretti and colleagues (1999), we did not find an association of increased anxiety symptoms in those with the s allele.

The present study suggests, but does not prove, a significant relationship between 5-HTTLPR genotype and acute response to SSRI therapy. The described differences should be confirmed prospectively in a concentration-controlled treatment trial, utilizing an SSRI with more selective serotonergic properties, such as citalopram or fluvoxamine.

References

Collier DA, Stober G, Li T, Heils A, Catalano M, Di Bella D, Arranz MJ, Murray RM, Vallada HP, Bengel D, Muller CR, Roberts GW, Smeraldi E, Kirov G, Sham P, Lesch KP . (1996): A novel functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene: Possible role in susceptibility to affective disorders. Mol Psychiatry 1: 453–460

Edenberg HJ, Reynolds J . (1998): Improved method for detecting the long and short promoter alleles of the serotonin transporter gene HTT (SLC6A4). Psychiatric Genetics 8: 193–195

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW . (1997): Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders SCID I: Clinician Version, Administration Booklet. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press

Foglia JP, Sorisio D, Kirshner M, Pollock BG . (1997): Quantitative determination of paroxetine in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography and ultraviolet detection. J Chromatogr Biol Med Appl 693: 147–151

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR . (1975): Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198

Hamilton M . (1967): Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 6: 278–296

Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stober G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP . (1996): Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J Neurochemistry 66: 2621–2624

Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL . (1996): Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 274: 1527–1531

Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Nebes R, Miller M, Little J, Stack J, Reynolds CF . (1999): A double-blind randomized comparison of nortriptyline and paroxetine in the treatment of late-life: Six-week outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 60(suppl 20): 16–20

Pollock BG, Everett G, Peril J . (1992): Comparative cardiotoxicity of nortriptyline and its isomeric 10-hydroxymetabolites. Neuropsychopharmacology 6: 1–10

Serretti A, Cusin C, Lattuada E, DiBella D, Catalano M, Smeraldi E . (1999): Serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) is not associated with depressive symptomatology in mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry 4: 280–283

Smeraldi E, Zanardi R, Benedetti F, Dibella D, Perez J, Catalano M . (1998): Polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene and antidepressant efficacy of fluvoxamine. Mol Psychiatry 3: 508–511

Young RC, Karaviorgou M, Kalayam B, Hull J, Alexopoulos GS . (1999): Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and response to nortriptyline in geriatric major depression. Society for Neuroscience Meeting, 29th Annual Meeting, Miami Beach, FL. Abstract 533.17.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants MH01509, MH01613, MH52247, MH30915, and AG05133.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pollock, B., Ferrell, R., Mulsant, B. et al. Allelic Variation in the Serotonin Transporter Promoter Affects Onset of Paroxetine Treatment Response in Late-Life Depression. Neuropsychopharmacol 23, 587–590 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00132-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00132-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Kynurenine pathway and white matter microstructure in bipolar disorder

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2018)

-

Personalized medicine in psychiatry: problems and promises

BMC Medicine (2013)

-

Serotonin transporter genotype and function in relation to antidepressant response in Koreans

Psychopharmacology (2013)

-

A Review of Pharmacogenetics of Adverse Drug Reactions in Elderly People

Drug Safety (2012)