Key Points

-

Provides a narrative of the development of the model of dentists with special interests.

-

Highlights the support of different stakeholders on a pilot initiative to train DwSIs in endodontics.

-

Investigates the potential of such initiatives to meet the need for moderately difficult endodontics.

-

Provides insight into how GDPs might wish to use DwSIs in future.

Abstract

Background The aim was to obtain stakeholders' views on the former London Deanery's joint educational service development initiative to train dentists with a special interest (DwSIs) in endodontics in conjunction with the National Health Services (NHS) and examine the models of care provided.

Methods A convergent parallel mixed methods design including audit of four different models of care, semi-structured interviews of a range of key stakeholders (including the DwSI trainees) and questionnaire surveys of patients and primary care dentists.

Results Eight dentists treated over 1,600 endodontic cases of moderate complexity over a two year training period. A retrospective audit of four schemes suggested that first molars were the most commonly treated tooth (57%; n = 341). Patients who received care in the latter stages of the initiative were 'satisfied' or 'very satisfied' with the service (89%; n = 98). Most dental practitioners agreed that having access to such services would support the care of their patients (89%; n = 215) with 88%; (n = 214) supporting the view that DwSIs should accept referrals from outside of their practice.

Conclusion This initiative, developed to provide endodontic care of medium complexity in a primary care setting, received wide support from stakeholders including patients and primary care dentists. The implications for care pathways, commissioning and further research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Endodontic care, as with most of dentistry, is predominately provided in primary care settings, across the National Health Service (NHS) and private systems, with cases of high complexity being referred to specialists, in either general practice or hospital settings. There has been a rise in referrals to hospital-based services from primary dental care since the introduction of the new dental contract in 2006,1 while hospitals are also required to manage waiting lists effectively and avoid patients waiting more than 18 weeks for care.2 Published guidelines on complexity of endodontics produced by the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS Eng)3 have had limited impact on care nationally, while those produced by the American Association of Endodontics (AAE)4 have been used to inform referrals to specialist services.

Within London, specialist training in endodontics is either self-funded by trainees who tend to then work in the private sector, or as part of the publically funded wider restorative dentistry training programme that produces hospital-based consultants. The latter can also opt to work within the private sector. Evolving health policy has emphasised changes to the system of educating and training the healthcare workforce;5 including transfer of the responsibility for education and training from national to local level and ensuring flexibility and innovation in the future provision of services.6 Developing intermediate education to build and recognise additional skills has become a focus for the NHS in the past decade,7,8,9,10,11 as has providing access for routine care in a setting closer to home through a broader range of primary care services.12

In 2004, the Department of Health and Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (UK) adapted the model of practitioners with special interests (PwSIs) from medicine and formally introduced a policy framework for the concept of dentists with special interests (DwSIs) within the NHS. This involved dentists working in primary care providing additional dental services to those within their generalist role.13 Two years later the same authorities set out the process of NHS appointments of DwSIs in endodontics in a guidance document.14 Similar schemes were described across five other competency areas of dentistry.15,16,17,18,19

A DwSI in endodontics was defined as being able to demonstrate a continuing level of competence in their generalist activity, an agreed level of competence in endodontics, and being contracted to the NHS to manage a number of patients requiring endodontic treatment of moderate difficulty.14 Published research on pilot schemes with DwSIs in oral surgery suggests that minor oral surgery may be cost efficient, support patient management and improve access for patients,20 and DwSIs in periodontics may improve access and produce positive clinical outcomes.21

In 2009 the London Deanery, in conjunction with a number of London Primary Care Trusts (PCTs), piloted and financed a two-year programme to train DwSIs in endodontics within the NHS in response to concerns about pressure on hospitals, skills and capacity in primary dental care.14,22 The aim of this programme, outlined by the Postgraduate Dental Dean of London Deanery was 'to reduce unnecessary referrals to hospitals, reduce extraction rates and train GDPs to undertake complex endodontic procedures within the primary care sector'.22 The educational aim for the programme was 'to provide a contemporary account of endodontology, which will enable general dental practitioners to develop the skills necessary to provide high standards of care for patients requiring endodontic treatment (of simple and moderate complexity) within NHS general dental services'.23 Interested practitioners were formally recruited across primary dental care in London, interviewed and approved for training. A description of endodontics of moderate difficulty was developed for this initiative by PB (Table 1) using the RCS Eng and AAE guidelines.3,4 Eight candidates from seven London PCTs successfully completed the training in April 2011, which used the simulation unit at London Dental Education Centre (LonDEC).24 Following mid-course evaluation the number of participating trainees reduced from nine to eight. An interim report produced by a specialist in dental and medical education showed positive educational outcomes that were found to be beneficial to both course participants and patients.25

This article describes the key findings from a mixed methods evaluation of this pilot programme to train DwSIs in endodontics. To protect the anonymity of individuals the findings will be described by PCT type and triage model, rather than individual scheme.

Aim of evaluation

The aim was to obtain stakeholders' views on London Deanery's service development initiative to train DwSIs in endodontics in conjunction with NHS PCTs and the models of care. The objectives for the evaluation included:

-

1

Examining service activity (number of NHS patients treated) during the pilot training programme. Quotas were set by educationalists and agreed by the sponsoring PCTs

-

2

Evaluating the effectiveness of the triaging system in ensuring that the patients accepted for treatment met the criteria of endodontics of moderate difficulty

-

3

Investigating the views of patients treated by the DwSI on their experience of the service and treatment received

-

4

Assessing primary dental care practitioners' views on the concept, systems and training of DwSIs

-

5

Exploring the views of the trainees, educators, commissioners and providers with regard to the past and future need for such enhanced skills practitioners and the lessons learned from the initiative.

Materials and methods

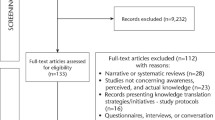

A convergent parallel mixed methods design,26 examining different perspectives was used: clinical activity, triage models, interviews with stakeholders including course participants, a cross sectional survey of a sample of primary care practitioners and a questionnaire survey of patients (Fig. 1).

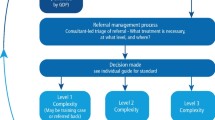

'Clinical activity' estimated the course participants' compliance with level of service activity commissioned by the sponsoring PCTs. Clinical activity on endodontics was available from pilot sites but not across secondary care. An external audit of cases that had been referred to DwSIs was undertaken where data collection systems were accessible to audit. This covered four different triage models used in the pilot programme: first, PCT-based triage where the patients were referred to the PCT and triaged by a restorative consultant; second, a community dental service (CDS) where an endodontic specialist triaged the referral before it was seen; third, hospital-based, where a restorative consultant triaged the referrals; fourth and finally, in-house triage where the trainee DwSI carried out triaging of the referrals (Fig. 2).

Patients treated by the DwSIs during the last four months of the training period and up to one year after the completion of the training programme were invited to take part in a written questionnaire survey to ascertain their perspective of the service provided. The data were anonymised and a descriptive analysis performed using Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011.

A postal questionnaire survey of primary dental care practitioners in London provided a 'Gatekeeper' perspective. This involved a stratified sample of general dental practitioners across six PCTs (equivalent to boroughs) with different arrangements. Based on a previous survey of GDPs in London,27 and in order to achieve a response from 5% of London GDPs (circa 200) all GDPs were sampled in each of the PCTs and surveyed using an instrument constructed on the basis of the literature, piloted and amended. Data were input to SPSS version 19.0 for analysis.

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were carried out with 19 stakeholders purposively sampled to represent trainees, educators, commissioners and providers. These interviews were conducted by one researcher (MA-H) and analysed using framework methodology,28 a matrix-based analytic method that facilitates rigorous and transparent data management such that all the stages involved in the analysis can be systematically conducted. The interviews were preceded by a focus group workshop conducted with the DwSIs, trainers, and a representative from London Deanery on the last day of their two year training programme that informed the topic guide and evaluation. The findings were synthesised in a mixed methods approach.29

King's College Hospital Research Ethics Committee approved the overall study as a service evaluation. The cross sectional survey of primary dental care practitioners was approved as research by King's College London Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: BDM/11/12-24). The patient survey was approved by NRES as part of a wider programme of PhD study by SE (Reference number: 10/H0808/116).

Results

Service activity commissioned and delivered

The volume of activity commissioned by the NHS (sponsoring PCTs) during the training period was in line with the programme requirements for acquiring the necessary competencies (100 cases per year); hence, the eight participants completing the programme treated over 1,600 cases of moderately difficult endodontics with variations in activity, in addition to their routine patients. The DwSIs projected, in interviews, that they could treat an average of two cases per week (if they were contracted to perform 1 day of endodontic treatments per week) and four cases if they were contracted for two days per week. This would translate to 800-1,600 patients being treated in one year by eight dentists with enhanced skills in endodontics.

Audit of referred and treated cases

The results of the audit of the four different triaging schemes (n = 550 cases) revealed that the patient care completed by DwSIs as part of their training was in line with the referral criteria agreed for DwSIs accepting external referrals (Table 1). In all the audited schemes the residents of the sponsoring PCT constituted the largest group of service users (49-66%). In the 550 audited cases, first molar teeth (upper and lower) were the most commonly treated cases (57%), with an average number of sessions per patient ranging from one to three; female patients were treated in the majority in each scheme (62% overall). There were differences in the profile of patients seen in general dental practice and the salaried services with the latter treating a larger number of children. Some inconsistencies were evident in the recording of cases referred to DwSIs by primary dental care practitioners, with cases rejected at triage level not being recorded across all schemes. Where data were available in the PCT-based triage model, it was possible to identify that 15% of the cases seen over a nine month period were rejected. Comparing patient profiles and treatment duration across schemes (Table 2), the hospital-based triage model was associated with the shortest treatment time (mean 40 days; range 0–469). The hospital-based triage model accepted 49% from the local borough, compared with 66% from the PCT-based model.

Patient experience

Of the 135 patients recruited for this evaluation, 96% (n = 130) responded to the first questionnaire that explored their views before receiving treatment from the DwSIs. Most were female (60%; n = 78) and within the 25-44 year age group (58%, n = 75). Just over half (52%; n = 68) identified themselves as 'British', while just under half (47%; n = 61) reported having had a third-level education (university degree level or higher). Ninety-eight percent (n = 127) of patients supported the view that they received a clear explanation for being referred and 89% (n = 116) of the patients were happy being referred to the DwSI endodontic service.

A response rate of 82% (n = 110) was achieved for the follow-up questionnaire within the first month after completion of their treatment. Most patients (89%; n = 98) reported being satisfied with the DwSI service and to have developed trust and confidence in the dentist who treated them (91%; n = 100). This satisfaction regarding the DwSI service was further confirmed by the majority not only reporting that they would recommend this service to their friends and family (83%, n = 91), but also that they would utilise this service again for any future root canal treatment (84%, n = 92).

Survey of primary dental care practitioners

Among the 243 dentists that responded to the mail survey (30% response rate), there was clear support for the DwSI in endodontics initiative among primary dental care practitioners and, for over half the respondents (57%; n = 139), a personal interest in receiving similar training themselves. Dentists who had used the services of DwSI in endodontics reported having referred an average of six cases during the course of the pilot training programme. While there was notably strong support for DwSIs, there was also notable dissatisfaction with current arrangements for primary dental care; almost all respondents (93%; n = 220) supported the view that they would perform more endodontic treatment on the NHS if 'reimbursed adequately', had 'more training' (86%; n = 207), and 'more time' 76% (n = 180) (Fig. 3). 'Direct referral' to the dentists with extended skills was considered as the most appropriate care pathway (81%; n = 195), with almost nine out of ten dentists (88%; n = 214) supporting the view that DwSIs should accept referrals from outside of their practice.

Views of key stakeholders

Interviews, supported by the focus group workshop, provided a clear view that this combined educational and service initiative had been developed to contribute to healthcare across four key domains (Fig. 4). First, by addressing service issues, most notably the 'void' in NHS service provision in primary care, which was resulting in 'waiting list pressures' in secondary care and 'patient complaints'. Second, it addressed 'quality' and 'outcomes' for patients allowing patients to 'receive care closer to home', 'retain their teeth', and do so 'within the NHS' and 'in a timely manner'. Third, it 'developed capacity' through education of primary care dentists. Fourth, and finally, there was the perception that it 'assisted with professionalism' – specialists were better able to utilise their specialist skills and it allowed generalists to facilitate access to endodontic care in the public sector for their patients rather than the alternative of referring patients to the private sector or merely providing dental extractions. Stakeholders viewed external triage processes as having benefit during the early stages of training in particular.

There was dissonance on a number of topics, most notably financial - some of those interviewed perceived the initiative as representing value for money, while others suggested that more evidence was required before such a conclusion may be drawn.

The interviews were carried out in the period immediately following completion of the training programme when the future of the service was unclear. These 'DwSIs in waiting' wanted support and recognition from the NHS. They wished to be integrated within the overall NHS dental system, both during and after training, to ensure the long-term success of the project. During the working group session participants described several systems-related issues with the contract. Concerns were related to the difficulties with triaging arrangements, managing cross-borough (PCT) flow of patients and finally delays in agreeing contracts between sponsoring NHS organisations (PCTs) and the potential DwSIs as illustrated by the following quotation:

'...if they [DwSIs] are not being paid the right amount, then they will just do treatment privately and it's of no benefit to NHS patients, which is the whole purpose.' (DwSI participant)

There was widespread support from the participants who undertook the pilot training for the service to be mainstreamed within the NHS if the system issues were resolved; particularly those relating to tariffs, contracts and accreditation.

Discussion

The findings of this mixed methods evaluation suggest that dentists completing the two-year programme to develop extended skills met the academic requirements of this educational initiative, which was strongly endorsed by an external educationalist.25 These dentists also achieved the clinical targets set for them during their training period, both in terms of the volume of patients treated and, where external audit was undertaken, appropriate case mix. Furthermore, this service was viewed positively by key stakeholders including primary dental care practitioners, patients using the service and commissioners, educators and providers. The findings of this evaluation are in keeping with other similar evaluations in minor oral surgery and periodontics, which also reported strong support from key stakeholders, particularly patients and referring practitioners.20,21

Strengths and limitations

There have been no evaluations of similar endodontic initiatives and only a few of specialist/special interest services in general.20,21,30 Thus, the findings from this mixed methods study provide important insight to new models of care and their acceptability. While the dental services in London may differ from other parts of the country, the issues that prompted the initiative are not peculiar to London and therefore the information is timely in relation to policy developments on care pathways in England; however, there are some limitations to this evaluation. The number of practitioners involved in the pilot was small, and the response to the survey of dentists was low (30%), despite the rigorous use of the Dillman approach.31 The expected response rate from healthcare professionals was 52-57.5%.27,32 Thus, these findings must be considered with caution. Given the support for innovation involving DwSIs, this suggests that the overall response is at best clearly very supportive and at worst equivocal as the surveys provided the opportunity for those strongly opposed to present their views. In contrast, there was a clear negative message about remuneration and training in endodontics in NHS primary dental care; a response that clearly fits with contemporary professional views.33,34 These findings show clear benefits to patients and practitioners from this initiative and service, which was perceived as providing a previously unmet need in the existing healthcare system.

The retrospective design meant the research team were dependent on available data, and additional information such as the number of referrals received by secondary care for endodontics during the same period was not available. Cost estimations were made as detailed costs in the pilot initiative were unavailable, possibly due to the significant changes that occurred both to deaneries and PCTs over this period as well as the commercially sensitive nature of the pilot. It is estimated that the cost of the two-year programme was approximately £100,000 for the teachers, teaching premises, materials and equipment with an additional £384,000 paid for by the commissioners to the trainee DwSI for treating the 1,600 teeth.

Consideration was given to establishing an appropriate control group to examine the true effect of the pilot itself as opposed to simply increasing the exposure of this group to a larger number of endodontic treatments. It can be argued that even if they were willing to participate, other GDPs or specialists may not necessarily make an appropriate comparison. The endodontic outcomes of this group of DwSIs are therefore being examined in a study being undertaken by SE, with the DwSIs being their own control assessing change in skills at the beginning and end of the training period.

There is a question mark as to whether the lack of skills to provide endodontics of moderate complexity is a result of lack of maintenance and development of established expertise at undergraduate level, or if it is a result of lack of appropriate training during undergraduate teaching.

The findings of this research should contribute to future workforce decisions made by Health Education England (HEE) and NHS England and their local offices, which have been tasked with identifying innovative means of adapting the healthcare workforce to meet the changing health (and oral health) needs of the population.6 The dental arm of the NHS Commissioning Board for Dentistry should consider dentists with extended education and skills as part of managed clinical networks,35 supported by the work of the Royal Colleges on developing dentists with extended skills.36 Clear integration of the scheme into the NHS structure and referral pathways across London with proper accreditation and remuneration of the dentists who successfully completed the training is essential; the new unified system, NHS England means centrally commissioned dental care without the barriers posed by postcodes. This is a unique opportunity to develop care pathways in dentistry and in prospective studies assess their cost-effectiveness against other modes of dental care delivery. Endodontic care is one area for development within a clear care pathway in which dentists with enhanced skills in endodontics, following completion of appropriate training, can play an important role in providing intermediate services, where they are currently lacking, ideally on direct referral (Fig. 5). This pilot provides a practical insight into developing an innovative model of care, as advocated in the reshaping of healthcare.37

At the time of evaluation, and going to press, there has not been a definitive process for accrediting all of the trained dentists within this pilot as intermediate care providers into the NHS. Some of the trained dentists have recently been formally recognised by their commissioners and have commissioned services. The cost of not using these individuals (trained using public funds) is significant if they are lost to the private sector. There needs to be a system for commissioning and rewarding dentists with additional education and skills within the NHS system. Looking to the future there is an overwhelming need for current skills to be harnessed within the NHS and for services to be evaluated using more comprehensive data across primary and secondary care to examine cost-effectiveness, benefits for patients, patient outcomes, as well as the implications for the dental workforce and the health system in general.

Conclusion

The findings of this mixed methods study highlight the potential for combined educational and service initiatives to deliver care of medium complexity in a primary care setting, and the concept received wide support from stakeholders, including patients and referring dentists; however, it highlights the challenge of mainstreaming services within the NHS.

Conflicts of interest

RR proposed the idea of developing the equivalent of GPwSI in dentistry to the Department of Health during his tenure as Dean of the FGDP; he subsequently initiated and managed the project for the London Deanery when employed by the deanery. EJ is the postgraduate Dental Dean for London under whose auspices the programme was run. JEG was on the Senior Dental Leadership Team in the Department of Health when the decision was taken to set up a DwSI in endodontics and the Dental Public Health representative in the working group. SE was a teacher on the DwSI course. PB was the educational lead for the London DwSI in Endodontics Programme, and was responsible for the patient triage of three of the DwSI participants.

References

NHS Information Centre. Hospital episodes satistics online: main procedures and interventions. Online information available at http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=897 (accessed June 2014).

The National Health Service Commissioning Board and Clinical Commissioning Groups (responsibilities and standing rules) Regulations 2012. Statutory instruments, 2012. Online regulations available at http://www.nhs.uk/choiceintheNHS/Rightsandpledges/Waitingtimes/Documents/nhs-england-and-ccg-regulations.pdf (accessed June 2014).

Clinical Effectiveness Committee R C S England. Restorative dentistry index of treatment need: complexity assessment. London: Department of Health, 2001. Online article available at http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/fds/publications-clinical-guidelines/clinical_guidelines/documents/complexityassessment.pdf (accessed June 2014).

American Association of Endodontists. AAE endodontic case difficulty assessment form and guidelines. Chicago: AAE, 2006.

Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London: DH, 2010.

Department of Health. Liberating the NHS: developing the healthcare workforce from design to delivery. London: DH, 2012.

Williams D M, Medina J, Wright D, Jones K, Gallagher J E . A review of effective methods of delivery of care: skill-mix and service transfer to primary care settings. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 53–60.

Gallagher J E, Wilson N H . The future dental workforce? Br Dent J 2009; 206: 195–199.

Department of Health. Practitioners with special interests: bringing services closer to patients. London: DH, 2003.

Department of Health. Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for the community. London: DH, 2006.

Department of Health. A high quality workforce: NHS next stage review. London: DH, 2008.

NHS Commissioning Board. Everyone counts: planning for patients 2013/14. London: NHS Commissioning Board, 2013.

Department of Health, Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (UK). Implementing a scheme for dentists with special interests (DwSIs). London: DH, 2004.

Department of Health, Dental and Optical Services Division, FGDP (UK). Guidelines for the appointment of dentists with special interests (DwSIs) in endodontics. London: DH, 2006.

Department of Health, Dental and Optical Services Division, FGDP (UK). Guidelines for the appointment of dentists with special interests (DwSIs) in periodontics. London: DH, 2006.

Department of Health, Dental and Optical Services Division, FGDP (UK). Guidelines for the appointment of dentists with special interests (DwSIs) in minor oral surgery. London: DH, 2006.

Department of Health, Dental and Optical Services Division, FGDP (UK). Guidelines for the appointment of dentists with special interests (DwSIs) in orthodontics. London: DH. 2006.

Department of Health, Dental and Eye Care Services, FGDP(UK). Guidelines for the appointment of dentists with a special interest (DwSI) in conscious sedation. London: DH, 2007.

Department of Health, Dental and Optical Services Division, FGDP (UK). Guidance for the appointment of dentists with special interests in special care dentistry. London: DH, 2009.

Pau A, Nanjappa S, Diu S . Evaluation of dental practitioners with special interest in minor oral surgery. Br Dent J 2010; 208: 103–107.

Cheshire P D, Saner P, Lesley R, Beckerson J, Butler M, Zanjani B . Dental practitioners with a special interest in periodontics: the West Sussex experience. Br Dent J 2011; 210: 127–136.

Jones E . Dentists with specialist interest (DwSI): London Deanery and London Primary Care Trusts meeting notes. London Deanery and London Primary Care Trusts, 2008.

Briggs P, Porter R, Karunanayake G, Eliyas S . Dentist with special interest (DwSI) in endodontics: modular syllabus and training manual. London Deanery 2009–2010. Unpublished.

London Dental Education Centre (LonDEC). Clinical skills training classroom. Online information available at https://www.londec.co.uk/Facilities/Skills-Training-Classroom.html (accessed June 2014).

Holsgrove G . Mid-course evaluation of a course for dentists with a special interest in endodontics. London: The London Deanery, 2010.

Cresswell J W, Plano Clark V . Choosing a mixed methods design. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles: Sage; 2007.

Gallagher J E, Williams D, Trathen A, Wright D, Jones K . Oral surgery services: skill-mix and service transfer to primary care settings: report to NHS and GST Charity. London: King's College London Dental Institute, 2010.

Ritchie J, Spencer L, O'Connor W . Carrying out qualitative analysis. In Ritchie J, Lewis J (eds) Qualitative research practice. London: SAGE, 2003.

Creswell J, Plano Clark V . The nature of mixed methods research. In Creswell J, Plano Clark V (eds) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. pp 1–18. London: Sage, 2011.

Dyer T A . A five-year evaluation of an NHS dental practice-based specialist minor oral surgery service. Community Dent Health 2013; 30: 219–226.

Dillman D A . How to improve your mail and internet surveys. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Cook J V, Dickinson H O, Eccles M P . Response rates in postal surveys of healthcare professionals between 1996 and 2005: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 160.

Davies B J, MacFarlane F . Clinical decision making by dentists working in the NHS General Dental Services since April 2006. Br Dent J 2010; 209: E17.

Brocklehurst P, Tickle M, Birch S, Glenny A M, Mertz E, Grytten J . The effect of different methods of remuneration on the behaviour of primary care dentists. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 11: CD009853.

National Health Services Commissioning Board. Securing excellence in commissioning NHS dental services. Leeds: NHSCB, 2013.

Working Group on 'Dentists with Enhanced Skills'. Initial report for the Dean of the FDSRCS (Eng): policy and action recommendations. Faculty of Dental Surgery RCSEng, 2013. Unpublished.

The King's Fund. Transforming the delivery of health and social care: The case for fundamental change. London: The King's Fund, 2012.

Acknowledgements

This evaluation could not have been undertaken without the support of dental public health consultants in London, NHS commissioners, dentists and their patients. Thanks is due to stakeholders who gave up their time to be interviewed, general dental practitioners in London for participating in the questionnaire survey and the Dental Services Division of the BSA for assistance with data. The project was funded by the London Deanery. Special thanks to the following individuals who assisted with this study: Swapnil Ghotane, Caroline Comyn, Nick Kendall, Paul Newton, Claire Robertson, Desmond Wright and J. T. Newton.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Haboubi, M., Eliyas, S., Briggs, P. et al. Dentists with extended skills: the challenge of innovation. Br Dent J 217, E6 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.652

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.652

This article is cited by

-

Dentists' preparedness to provide Level 2 services in the North East of England: a mixed methods study

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Novel tier 2 service model for complex NHS endodontics

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Initial periodontal therapy before referring a patient: an audit

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Fortitude and resilience in service of the population: a case study of dental professionals striving for health in Sierra Leone

BDJ Open (2019)

-

Dual training of dental nurses: stakeholder views on an innovative pilot

BDJ Team (2018)