Key Points

-

This paper describes the Apothecaries

-

Shows how the Apothecaries by becoming general medical practitioners were 'fenced off' from the dentists

-

Comments on the numerical increase in dentists in the early and mid-nineteenth century

-

Demonstrates the ethico-legal, ethico-social, and ethico-professional effect of the 1815 Apothecaries Act on the emerging profession of dentistry.

Abstract

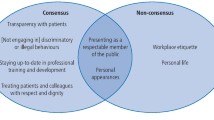

The Apothecaries Act of 1815,1(revised by the Act of 1825)2 has been credited with being the most important forward step in the education of the general medical profession in the nineteenth century,3 although a closely argued revisionist view of its significance by S W F Holloway4 makes clear his view that it was also a successful and deeply reactionary political move by the physicians to emasculate a rival group growing rapidly in numbers and power. This paper demonstrates that the Act also created a distance between the true dentists and others, like the chemists and druggists, who carried out dental functions. By so doing the Act defined the social identity of the profession of dentistry, in its numbers, status, nineteenth century reform and pattern of education. The paper proposes the apothecary/general medical practitioner as a social as well as ethical role model for the general dental practitioner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Who were the apothecaries, and why was an act needed?

The aim of the well intentioned campaign to undertake medical reform in the latter part of the eighteenth century was to make good a perceived deficiency in the professional management of healthcare. This perceived deficiency had developed as part of the cycle of legal control and relaxation which the medical profession had undergone pretty well since records began. (The same sort of loss of control had also affected the operator for the teeth, who was legally free to pursue his activities, as explained in a previous paper, but who was at times socially constrained by church or guild powers.5) In turn in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Church registrations had been instituted and lapsed, and in their place more local influences had grown and faded. Whereas in the seventeenth century an operator for the teeth like Charles Allen had to be a member of the Barbers and Surgeons Guild of York, during the eighteenth century this sort of guild membership had ceased to be obligatory, and the last entries in the Egerton MS listing Barbers, Surgeons, and their apprentices in York, are dated 1784.6 What was true of York was true elsewhere, though the dates varied, and without this tight local control, and in the absence of any nation-wide alternative, medicine was very patchily regulated.

As a consequence, in the words of Clause VII of the Act; '...much mischief and Inconvenience has arisen, from great Numbers of Persons in many parts of England and Wales exercising the Functions of an Apothecary, who are wholly ignorant and utterly incompetent to the Exercise of such Functions, whereby the Health and Lives of the Community are greatly endangered; and it is become necessary that Provision should be made for remedying such Evils.'7

The result of all the good intentions and hard work of the medical reform group who tried to remedy this was the deeply disappointing and flawed Apothecaries Act. Clause XV in particular was to cause great trouble; '...no Person shall be admitted to any such Examination for a Certificate to practise as an Apothecary, unless he shall have served an Apprenticeship of not less than five Years to an Apothecary, and unless he shall produce testimonials to the Satisfaction of the said court of Examiners of a sufficient Medical Education, and of good moral Conduct.' Even after this clause was modified in 1825 to allow for the apprenticeship to have been served with a Member of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of London, Edinburgh, or Dublin, or to a Surgeon in the Army or Navy (note that the Physicians were above all this), the examination to be allowed to compound or dispense medicines had still to be held by the Society of Apothecaries. The second part of the essay will show the effect this had.

Difficulty immediately arose, for there was no adequate definition of an apothecary, and the Society of Apothecaries exercised their new powers thoroughly and widely. In 1776 Adam Smith had defined the apothecary by function as the physician of the poor in all cases, and of the rich when the distress or danger is not very great.8 Most unfortunately for the Apothecaries, however, the Act contained no definition of what were the functions and duties of an apothecary, except as: a mere retailer of simples, and the unpaid compounder of physician's prescriptions.9 Those to whom the Act applied, or perhaps those who thought the Act applied to them, defined themselves by complying with the terms of the Act, so the argument was circular, and resulted in a large catchment area. Others were driven into the fold by the prosecutions (86 between 1820 and 1832)10 which the Society of Apothecaries launched subsequent to the Act. As a result, the term apothecary or surgeon-apothecary came to be applied to nearly all medical men, and is accurately represented now by the general medical practitioner.

Some idea of the range of activity within this definition can be gained by reference to three mid-Victorian novels. Each of these, William Makepeace Thackeray's partly autobiographical Pendennis of 1848–50,11 and the second and third of Anthony Trollope's Barsetshire novels, Barchester Towers of 1857–5812 and Dr Thorne of 185813, appeared just before the Medical Act of 1858.14 This Act succeeded in achieving the reform which the pioneers had hoped for, and in a way much more in keeping with their intentions than the Apothecaries Act, and it also effectively signalled the end of the use of the term apothecary for a medical man.

From a dental perspective the character 'Old Scalpen', who appears fleetingly in Barchester Towers, is the most interesting of the seven fictional apothecaries in the books. This is because he was a retired apothecary and toothdrawer, confirming the overlapping of such function in a great Cathedral City (the novels are based on Salisbury). Christine Hillam, in her book Brass Plate and Brazen Impudence gives details of 19 real life counterparts to Scalpen in the provinces in 1855.15

Equally interesting from the social point of view is the invitation extended to Scalpen by Mrs Proudie, the Bishop's wife, to attend her reception. This was the first time he had been led to an awareness of the new social position of the apothecary following 40 years of the effect of the Act in creating the general medical practitioner as a professional out of the apothecary as tradesmen.16

'Dr Thorne', the eponymous hero of the third Barsetshire novel, was both a gentleman by birth, and a qualified physician. However, on settling in a little village at the commencement of the novel he added the business of dispensing apothecary to his activities. By doing so and, as Trollope puts it, consulting the comforts of his customers more than his dignity, he is much reviled and not regarded as a proper doctor by many, including his medical conferes. In fact, the novelist understates the position, Holloway in 196417 points out that as late as 1834, Members of the Royal College of Surgeons, and Licentiates of the Society of Apothecaries, had to be disfranchised to qualify as licentiates of the College of Physicians. For a real life physician to do as Thorne did and to move back to practise as an apothecary was indeed to risk all the opprobrium the fictional character received.

In Thackeray's novel Pendennis apothecaries appear in five guises, two of them and a physician being illustrated by the author's own pen to give us a delightful idea of what the Victorian medical man looked like. These descriptions provide a good representation of the range of understanding of the term, bracketed as it were between Trollope's gentleman and tradesman. Thackeray's attitude to the apothecary's trade could hardly differ more from Trollope's. In Pendennis the hero's father, a Cornish gentleman fallen on hard times, who betters himself from selling toothbrushes and perfumery in Bath by becoming an apothecary to the person and family of Lady Ribstone, had had to apprentice himself to a maternal uncle, a London apothecary of low family and coarse mind, with his 'odious calling' and 'detested trade'. Of the same sort of status, there is the unnamed apothecary who lived in the Strand, and who comes, with his lancet in his pocket and with his apprentice, at the bidding of the Physician Goodenough (Fig. 1a, 1b) to bleed 'Pen' the hero of the novel.

The others are of the new breed of general medical practitioner, though their title has not yet changed to 'doctor'. There is the local apothecary, Huxter, (Fig. 2) very much the amiable country GP in Pen's country town of Clavering, and his son, young Samuel Huxter, Pen's rival in love, who is studying surgery at St Bartholomew's (Fig. 3) who achieves his MRCS during the course of the novel, and will be one of the new generation of doubly qualified MRCS ASA doctors.

How the dental profession emerged from obscurity

Thackeray gives important parts to play to his physician and five apothecaries in his novel. Only in one sentence does he reveal the existence of such a being as a dentist, where 'Lady Rockminster' complains that; 'That horrid Grindley, the dentist, will keep me in town another week.' At least the fictional existence of such a being can be welcomed. The portrayal of a representative of 'the carriage trade' taking advantage of the London season to receive her dental treatment from a dentist in Town, rather than locally, is accurate, the pattern persisting well into the twentieth century. The proportion of one dentist to five medics is not inappropriate for the mid-nineteenth century, and at the start of the century even this would have been an exaggeration.

It is a sobering reflection for those who enjoy the status dentistry confers on its practitioners today, to be reminded of their invisibility 200 years ago. In 1808 a bill known as Dr Harrison's Bill was drafted by 'The Associated Faculty', a group pressing for reform in medicine. The group had had support at the very highest level, from William Pitt and Spencer Perceval, in addition to having their postage free from the Treasury.18 Dr Harrison himself was an Edinburgh graduate, and Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, Mr Forster, Master of the Royal College of Surgeons, and Sir George Baker, President of the Royal College of Physicians, among others almost equally illustrious, were in the group.

The Bill called for the 'establishment of a medical register on which the names of all those qualified as physicians, surgeons, midwives, apothecaries, veterinary practitioners, chemists, druggists, and vendors of medicine would be entered.'19

Dentists are conspicuously absent from this list of qualified medical and para-medical operators. This invisibility is almost certainly a result first of the scarcity of numbers of true dentists compared with the other medical disciplines listed, and second, of the ubiquity of the dental function, when the greatest part of dental healthcare was tooth-drawing. As a previous paper showed, 'everybody' did it, and in one way or another such dental healthcare was accessible to all at the end of the eighteenth century.20 Also, though apprenticeships existed in dentistry, there was no way at the time for dentists to comply with the term 'qualified'.

There was a sufficient number of dentists for the profession to have been recognised by the name at the turn of the century in the major metropolitan centres, and the thin strand of dental healthcare which stretched backwards in time from then is shown by the historical work of Menzies Campbell (From a Trade to a Profession)21 and Anne Hargreaves (White as Whales Bone).22 There was though, a substantial bar to further progress in establishing a professional identity, for liberty to all to perform dental operations meant that many others than those calling themselves dentists were able to draw teeth and perform other dental care functions, among them the apothecaries.

This would have continued to be an almost insoluble problem had not the Georgian Apothecaries Act been passed. Dentistry proved to be very lucky, the passing of the Act was a most close-called business, for it was passed by a majority of one on the last day of the session.23 Of crucial importance was the omission of dentistry from a mention in the context of the work of the apothecaries, and so the dental discipline remained free to develop in its own way and at its own pace, as it had been since the Henrician Acts of the sixteenth Century.5

Following the 'success' of the physicians with the Apothecaries Act, the Surgeons rushed to petition the House of Commons to present An Act for enlarging the Charter of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, and this was passed by the Lower House.24 It was, however, rejected in the Lords. The Surgeons might in their turn have overlooked the dentists in their search for extended control, but they did not get what they wanted, and again the dentists were not troubled.

This is by definition a dentist-centred paper, and to categorise an apothecary by his ability to draw teeth is, of course, an absurdity and is not the intention of the paper. The point must be made though, that they could and did perform that function if they so wished, and it is possible to picture two at least of Thackeray's apothecaries doing so as part of their 'odious trade' along with blood-letting, and as Trollope's 'Scalpen' did. John Woodforde25 points out, quoting from Parson Robert Kilvert's diary written between 1870 and 1879, that a countryman could attend the doctor and expect minor surgery '"Hulbert ... had been to the doctor and had seven teeth and 'snags' pulled out, and three knubs or tumours removed from his head"..."it made I sweat"...'and once I should have liked to knock the doctor through the door'.''

As to numbers, it was said in 1833 that: in the country, the distinction of three branches of the profession (Physician, Surgeon, Apothecary) does not exist ... all over England the medical practitioners are also apothecaries ... even in the metropolis, probably nine-tenths of the practice is in the hands of persons who dispense drugs ... now by this Act, all these persons, constituting as they do all but the entire medical profession throughout England, must, in the first place, be licentiates of the Apothecaries' Company.26

In the 10 years between 1823 and 1833 no fewer than 4,395 candidates presented themselves for examination as Apothecaries, and only 200 less at the Royal College of Surgeons, although there would have been a great deal of overlap.27

The Act had separated this entire large group from the dentists without any action of the dentists needed either then or subsequently to separate themselves from the group. There is no need to assume that there was any consciousness of this effect at the time, in fact the force of this paper is that it is just such unlooked-for and insensible changes in society which can have enormous significance from an historical perspective. These figures make it quite clear that had these, who as has been shown, were the general medical practitioners of the day, and those many more who were to come, not been withdrawn from the potential field of dentistry into general medical practice, the identification and registration of dentists 50 years later almost certainly could not have happened.

Having been established under the administrative umbrella of the Society of Apothecaries, they moved en masse to registration under the terms of the 1858 Medical Act, which also instituted the General Medical Council.28 The ground was thereby prepared for the registration of dentists as a clearly identifiable, and separate body, to be possible in 1878.

The medical profession which grew up after the 1815 Apothecaries Act no longer saw itself as a natural associate of the functions of dentistry, and in 1878 showed no enthusiasm for this identification and registration of dentists, as the British Medical Journal made obvious just before the Dentists Act of that year was passed: 'This Bill proposes to impose a complicated, extensive, and difficult series of duties on the General Medical Council ... and if the Council have to undertake the tutelage and charge of dentists at large they should at least have an opportunity of considering very carefully what is the proper machinery for carrying out their responsibility.'29 The task was indeed found to be an almost impossible burden by the Registrar of the General Medical Council,30 both as a consequence of the unexpectedly high numbers and, it must be admitted, the difficult personalities and low quality of many of the putative dentists.

The infusion of 'new blood' into dentistry

It is very improbable that any apothecary-dentist or chemist–dentist would have chosen to move exclusively to dentistry at the time of the Apothecaries Act or for a long time afterwards. Those few surgeon-dentists who did so faced considerable difficulty, as Part II of the paper will show. Not until the mid-century was the country wealthy enough to support many practitioners both limiting their activities to dentistry and staying in one place, as Hillam shows.31 The 'true' dentists only then had began to flourish and proliferate, as the towns and cities became more prosperous and services beyond mere tooth-drawing were required. No longer were practitioners just following their patient base as the wealthy moved with the 'season' from London to Spas and other places of recreation, but increasingly settling permanently.

The sheer scale of the change which followed the Act of 1815 in the dental profession is shown by Christine Hillam in her book Brass Plate and Brazen Impudence,32 already mentioned, which quantifies the explosion of dental practice outside the metropolitan centres. It is the remarkable growth in numbers and identity which, amongst other matters, this paper addresses. The logical error possibly inherent in a 'Post hoc ergo propter hoc' survey of historical events (happening after the thing, therefore happening because of the thing) needs to be kept in mind, but the argument for a central position of the 1815 Act can be made convincingly.

The importance of the Act in the increase in dental numbers was not necessarily to the credit of the profession. The person seeking to make a 'medical' living was prohibited by law from becoming an apothecary without training and examination, and from seeking to become a chemist or druggist without at least an apprenticeship, but nothing stopped all manner of 'great rogues'33 calling themselves dentists, and these undesirables can be reckoned in part at least to be of the type who formerly were among the 'great numbers of....wholly ignorant and utterly incompetent'7 persons who set themselves up as apothecaries or chemists before the Act stopped them doing so.

This un-disciplined entry to dentistry may not have been all bad in its effect, Hillam suggests that the worst of them failed very rapidly, and it must be acknowledged that in human affairs, rapid change, and a laissez-faire 'people broth' can result in healthy cultural progress, in complete contrast to the hidebound resistance to change exemplified by the Physicians in this story. In the case of dentistry this seems to have been the case, and the 'second generation' survivors rapidly sought respectability.

Before the Acts, the newcomers would have been in direct competition with any local apothecary who operated as Scalpen did, as a tooth-drawer and supplier of dental services, and this would inevitably have presented problems, since the limits of their function were undefined. As it now was, they were dentists, and dentists only, they could not trespass in any way on the apothecaries' territory, even if the apothecaries could trespass on theirs to a limited extent. They could now co-exist with the apothecary/general medical practitioner, and with the chemist/dentist without too much friction, for as has been truly said, good fences make good neighbours, and although there is no evidence that the Act was intended to benefit dentists, it erected two fences, which clarified the image of the dentists, and went a considerable way to make easier the rapid increase in their numbers which took place in the early nineteenth century.

The curious feature of this is that it became increasingly clear that the insertion of dentists into the social ladder had taken place beside the veterinary practitioners in the list in Dr Harrison's Bill19 given earlier, between the apothecary/general medical practitioner and the chemist, even though many chemists practised dentistry, as the next part of the paper will show. And so it was that the apothecaries became the social and educational medical backdrop against which the dentists could see themselves sculpted in high relief, and with whose their own status and education could be compared.

References

An Act for better regulating the Practice of Apothecaries throughout England and Wales. 55 Georgii III C.194. 12th July 1815.

An Act to amend and explain an Act of the fifty fifth year of His late Majesty, for better regulating the Practice of Apothecaries through England and Wales. 6 Georgii IV C.133. 6th July 1825.

eg Cope Sir Z 'Influence of the Society of Apothecaries on Medical Education'. Br Med J 1956; 1: 1–6.

Holloway SWF . The Apothecaries Act, 1815; A Reinterpretation. Med Hist 1966; 10: 107–129 221–236.

Bishop M, Gelbier S, Gibbons D . Ethics – the early division of oral health care responsibilities by Act of Parliament. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 51–53.

Cohen RA . Introduction to Allen C. The operator for the Teeth. Limited edition of 250 copies, Dawson of Pall Mall 1969 p.iv.

An Act for better regulating the Practice of Apothecaries throughout England and Wales. 55 Georgii III C.194. 12th July 1815. VII.

Smith A An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. 1776 Everyman ed. 1910 Vol I p100 (quoted in Holloway 1966 op. cit. p108).

Lancet 1826; 10: 594–95 (source Holloway 1966 op.cit pp221–2).

Holloway 1966 p.229.

Thackeray WM Pendennis. London 1848–50 Smith, Elder & Co, 1878 edition in 2 vols.

Trollope A Barchester Towers. London 1857: Penguin Classics Edn 1987.

Trollope A Dr Thorne. London 1858: Penguin Popular Classics Edn 1994.

An Act to regulate the qualifications of practitioners in medicine and surgery. 21 & 22 Vict. Cap. 90 2nd August 1858.

Hillam C Brass Plate and Brazen Impudence. Liverpool 1991: Liverpool Universty Press pp.19–20.

Trollope A Barchester Towers. Mrs Proudie's Reception. Vol I Chapter 10. London 1857: Penguin Classics Edn 1987.

Select Committee on Medical Education 1834 (6602-ii), xiii, part ii, Q.4902-6, pp30-1. Quoted in Holloway S W F Medical Education in England 1830-1858: A Sociological Analysis. History 1964; 49: 306.

Select Committee on Medical Education 1834 (602-I), xiii, part I, Q.4406-19, pp.304–6. Quoted in Holloway S W F The Apothecaries' Act 1815: A Reinterpretation Medical History. 1966 Vol X No.2 p118.

Holloway 1966 Op. cit p117.

Bishop M, Gelbier S, Gibbons D . Ethics – dentistry and toothdrawing in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in England. Evidence of provision at all levels of society. Br Dent J 2001 191: 575–580.

Menzies Campbell J From a Trade to a Profession. 1958 private printing.

Hargreaves AS White as Whales Bone: Dental Services in Early Modern England. Leeds: Northern Universities Press 1998.

Report from the Select Committee on Public Petitions 1833. Appendix 296 p251 (source Holloway op. cit.).

The Journals of the House of Commons Session 1814-1815, 8 November 1814 to 7 January 1816, Vol.70, p461 (source Holloway op. cit. p128).

Woodforde J The Strange Story of False Teeth. London: Routledge & Keegan Paul 1968 pp.35–36.

The Companion to the Newspaper, and Journal of Facts in Politics, Statistics, and Public Economy August 1833 p119 (source Holloway 1966, op cit.

Select Committee on Medical Education 1834 (602-III) Part III. Appendix 7 p.101 (source Holloway op. cit. p235).

The Medical Acts and the Dentists Act, Together with the Sections of other Acts which Affect the General Medical Council. 1858 (21 & 22 Vict. Cap.90) 2nd August 1858.

The Dental Practitioners' Bill. Editorial. Br Med J March 2nd 1878; Vol. I p.307.

The Right Hon. Francis Dyke Acland M.P Address to the Dental Board of the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 1921; 24: 1134–1135.

Hillam CF The development of Dental Practice in the Provinces from the late 18th century to 1855. PhD Thesis 1986 University of Liverpool.

Hillam C Brass Plate and Brazen Impudence. Liverpool: 1991 Liverpool University Press.

Tait's Edinb. Mag., 1838, 5, 197. Quoted in; Menzies Campbell J. From a Trade to a Profession 1958 private printing p.83.

Acknowledgements

The paper by S W F Holloway is strongly recommended as further reading, and acknowledgement is here given to it as a source in depth for the medical background for this paper. Also Christine Hillam's account is much to be recommended. Mr Christopher Liddle, late of the College of Law, assisted with advice and the location of legal documents essential to the paper. Mr Christopher King helped with material from the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bishop, M., Gelbier, S. Ethics: How the Apothecaries Act of 1815 shaped the dental profession. Part 1. The Apothecaries and the emergence of the profession of dentistry. Br Dent J 193, 627–631 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801645

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801645