Key Points

-

The diagnosis of plasma cell gingivitis is rare.

-

Intraoral changes apparently related to khat have rarely been reported earlier.

-

Plasma cell gingivitis apparently related to khat has not been published in the literature.

-

More cases can probably be expected in the future due to increased immigration.

Abstract

Plasma cell gingivitis (PCG) is characterized by massive infiltration of plasma cells into the subepithelial tissue. It is a rare condition; the cause of which is still not fully understood. A case of PCG is reported in the mandibular gingiva probably caused by chewing khat. This report is the first, as far as we know, that relates PCG to the use of khat. The histological examination revealed infiltration of polyclonal plasma cells without signs of fungus, tuberculosis or malignancy. It is concluded that the changes were compatible with an allergic-like reaction. The patient, a 30-year-old immigrant from Somalia, revealed in a subsequent consultation that he regularly used khat. The leaves are placed in the buccal sulcus. The PCG disappeared within two weeks of the use of khat being discontinued. Dental surgeons (periodontists) in Europe and the New World will, due to increasing immigration from Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, meet more patients who regularly use khat. This means that PCG and other khat related intraoral changes will become more common in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The habit of chewing the leaves of the khat plant (Cahta edulis) has existed for many hundreds, if not thousands of years in the countries of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.1 It can be likened to the chewing of betel nuts by the peoples of Southeastern Asia and tobacco by some Americans and Europeans. The chemical constituents of khat leaves have been extensively studied by Kalix,2 who was able to demonstrate that there are three main alkaloids present; namely chatinone, norpseudoephedrine (chatine) and norephidrine. Chatinone (alpha-amino-propriophenone) has a pronounced effect on the central nervous system, although all three have similar peripheral effects. Chatinone has very similar sympathomimetic properties to amphetamine.1,2,3 Both liberate catecholamines from the pre-synaptic nerve endings, and this is probably the reason why the use of khat leaves is so popular in these countries. The following effects have been reported after the use of khat: euphoria, anorexia, insomnia (lack of fatigue), hyperactivity, excitation, hyperthermia, increased respiration, mydriasis, arrhythmias, hypertension, and constipation.1,2,3 The first of these effects is the one sought by those addicted to the habit, which produces psychological rather than physiological dependence.2 It is known2 that the leaves of the khat plant also contain tannic acid, and it is presumed that this compound is responsible for the stomatitis from which many of these people suffer, as well as the gastro-intestinal side effects.2,4

A case of gingivo-stomatitis, which in respect of the gingiva was diagnosed as plasma cell gingivitis apparently caused by chewing khat leaves, is reported for the first time.

Case report

The patient was a 30-year-old male from Somalia; he had been referred to our department by his dental surgeon due to gingivitis-like changes in the left mandibular gingiva. The condition had not responded to the usual periodontal treatment of scaling and normal hygienic measures, and had been present for some two months.

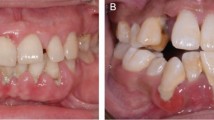

Physical examination revealed pronounced changes in the left side of the mandibular gingiva together with similar changes in parts of the maxillary area. These comprised reddening and swelling of the gingiva, including both the marginal and alveolar gingiva. They were also present in the sulcus. Similar changes could be seen in the mucosa of the cheek within the same area. There were scattered fibrin-covered ulcerations (Fig. 1) and desquamination of the epithelium could be observed following drying. Roentgenological examination showed marked destruction of bone in the affected area, particularly that corresponding to LL6 (36) and LL7 (37), where there was bone loss and furcation involvement (Fig. 2). The general health of the patient was good and he stated that he took no medication. He was unable to offer any information regarding the possible cause of his illness. However, he did disclose that he had noticed some swelling of the regional lymph glands during the last couple of months.

Biopsy was carried out under local anesthesia, partly of the gingiva and partly of the mucosa of the cheek.

The histological examination showed surface epithelium with psoriasiform hyperplasia, exocytosis and spongiosis. Small collections of neutrophils (micro-abscesses) were identified in the parakeratin layer. No candidal hyphae could be found following periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. There was marked dilatation and an intense inflammatory infiltrate in the connective tissue dominated by plasma cells (Figs 3a., 3b). Clonality was studied due to the possibility of myeloma, but this showed that the plasma cells were polyclonal and thus represented an unspecific inflammatory infiltration. It was concluded that it was a case of plasma cell gingivitis-stomatitis with a possible allergic basis. This conclusion was reached owing to the fact that massive polyclonal infiltration was present together with epithelial changes and no fungal infection could be identified.

More thorough questioning of the patient disclosed that he chewed khat almost daily. He was advised to discontinue the practice as there were changes in both the soft tissue and alveolar bone. He attended the department for follow-up examination some two weeks later and there was almost complete healing of the affected gingiva and mucosa of the cheek. Thereafter the patient refused to attend for further examination despite efforts to follow-up the case.

Discussion

Plasma cell gingivitis (PCG) is a rare condition characterized by diffuse and massive infiltration of plasma cells into the sub-epithelial gingival tissue.5,6,7 Clinically, the illness presents as a diffuse reddening together with oedematous swelling of the gingiva, with sharp demarcation along the muco-gingival border.8 Ulceration is rare in the pathologically changed gingiva.6 The etiology of PCG is not clear, but due to the obvious presence of plasma cells many authors are of the opinion that it is an immunological reaction to allergens; these latter may occur in toothpaste, chewing gum, mint pastels and certain foods.5,6,7,8,9,10 It has been suggested that strong spices and some herbs such as chilli, pepper and cardamom may be important factors.5,8,9 Hedin et al.7 reached the conclusion, based on a material comprising 14 patients, that PCG is the result of an allergic reaction to bacterial plaque, even though this had been eliminated by means of conventional periodontal treatment.

The diagnosis requires haematological screening in addition to clinical and histopathological examination in order to exclude leukemia. Further, serological examination is needed to exclude connective tissue disease – first and foremost lupus erythematosus.10,11 Other possibilities with regard to the differential diagnosis are lichen planus and benign mucous membrane pemphigoid.5,10 The histo-pathological changes mimic those of other more serious conditions such as multiple myeloma, solitary plasmacytoma and Waldenströms macroglobulinaemia.5

Some authors6,12 sub-divide PCG into three types: 1) caused by an allergen, 2) neoplastic, 3) unknown cause.

The present case belongs to type 1 inasmuch as the changes had developed after prolonged use of khat leaves. Remission occurred when the use of the leaves was discontinued. However, the actual site of the PCG was rather unusual. Many authors have found that the condition occurs in the anterior gingiva, most frequently in the maxilla. In our patient, the changes were confined to the facial gingiva of the left side of the mandibular region. This can be explained by the direct contact with the allergen (khat), which is usually placed in the sulcus, where it is retained for several hours in intimate contact with both the gingiva and mucosa. The condition is therefore compatible with a contact allergic reaction. The mucosa of the cheek and of the bottom of the sulcus showed clinical and histopathological changes as seen in PCG.

Involvement of sites other than the attached gingiva has been reported earlier.6,13 There is some disagreement among the various authors as to the part played by the habit of chewing khat leaves in the development of periodontal diseases. Hill and Gibson14 reported that the depth of periodontal pockets was significantly less on the side of the oral cavity used for chewing than on the opposite side. This applied to addicts using only one side for chewing, which appears to be the custom in the majority of these people. In contrast, Rosenzweig and Smith15 described a pronounced increase in periodontal disease in men from Yemen who used khat extensively. Considerable periodontal furcation involvement of the molar teeth was seen in our patient in addition to the changes observed in the mucosa of the cheek and gingiva. It is therefore highly probable, although not proven, that tannic acid was responsible for the intra-oral changes as seen in the present case.

In conclusion, dental surgeons (periodontists) in Europe and the New World should keep the condition in mind because of the increasing number of immigrants from Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Many of their immigrant patients will, in all probability, regularly chew khat. Thus, there is little doubt that the incidence of PCG and other complications related to the use of khat will increase in the future.

References

Serio FG, Siegel MA, Slade BF Plasma cell gingivitis of unusual origin. J Periodontol 1991; 62: 390–393.

Sollectio TP, Greenberg MS Plasma cell gingivitis. Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 73: 690–693.

Hedin CA, Kappe B, Larsson Å Plasma cell gingivitis in children and adults. A clinical and histological description. Swed Dent J 1994; 18: 117–124.

Reed BE, Barrett AP, Katelaris C, Bilous M Orofacial sensitivity reactions and the role of dietary components. Case reports. Aust Dent J 1993; 38: 287–291.

Macleod RI, Ellis JE Plasma cell gingivitis related to the use of herbal tooth-paste. Br Dent J 1989; 166: 375–376.

Gargiulo AV, Ladone JA, Ladone PA, Toto PD Case report: Plasma cell gingivitis A. CDS rev 1995; 88: 22–23.

Timms MS, Sloan P Association of supraglottic and gingival idiopathic plasmacytosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991; 71: 451–453.

Halbach H Medical aspects of the chewing of khat leaves. Bull World Health Organ 1972; 47: 21–29.

Kalix P Khat: A plant with amphetamine effects. J Subst Abuse Treat 1988; 5: 163–169.

Al-Meshal IA Effect of (alpha) chationone, an active principle of Catha edulis Forssk (khat) on plasma amino acid levels and other biochemical parameters in male wistar rats. Phytother Res 1988; 2: 63–66.

Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company 1995 pp 126–127.

Kerr DA, McClatchey KD, Regezi JA Idiopathic gingivostomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1971; 32: 402–423.

Luqman W, Danowski TS The use of khat (catha edulis) in Yemen. Social and medical observations. Am Intern Med 1976; 85: 246–249.

Hill CM, Gibson A The oral and dental effects of q´at chewing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 63: 433–436.

Rosenzweig KA, Smith P Periodontal health in various ethnic groups in Israel. Periodont Res 1966; 1: 250–259.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marker, P., Krogdahl, A. Plasma cell gingivitis apparently related to the use of khat: report of a case. Br Dent J 192, 311–313 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801364

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801364

This article is cited by

-

Traditional Somali Diaspora Medical Practices in the USA: A Scoping Review

Journal of Religion and Health (2023)

-

Qat and its health effects

British Dental Journal (2009)