Abstract

Periodontitis and gingivitis are highly prevalent inflammatory diseases of the oral cavity, and typically are characterised by the presence of dental plaque. However, other causes of oral inflammation exist, which can resemble plaque-induced gingivitis and periodontitis, and may thus first be seen by a dental practitioner. This paper aims to provide dentists with an understanding of the manifestations of systemic diseases to the periodontium and highlights anamnestic and clinical clues important for distinguishing between plaque-induced and non plaque-induced lesions. In the first part of this series immune-mediated and hereditary conditions as causes of gingival lesions were discussed; this second part highlights cancer-related gingival lesions as well as those caused by specific pathogens, medication or malnutrition. A clear clinical, epidemiological and visual overview of the different conditions is provided. Early diagnosis of non plaque-related causes of gingival lesions can be vital for affected patients. Therefore, dental practitioners should be aware of the various manifestations of systemic diseases to the periodontium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

Provides dental practitioners with an understanding of the manifestation of systemic diseases to the periodontium.

Highlights elements in the clinical assessment which will aid in establishing a diagnosis.

Presents different conditions, exemplified by clinical photographs.

Introduction

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we discussed immune-mediated, autoinflammatory, and hereditary conditions, which can be observed in the gingivae.1 We also provided a general introduction to this topic and overview of relevant anatomy and terminology; readers are therefore referred to that publication. In this article, the second part of this series, we discuss cancer-related gingival lesions, infective and other causes of gingival inflammation. The potentially malignant disorders discussed are a group of diseases that have high malignant transformation rates and should therefore be diagnosed early. Established systemic cancer, such as leukaemia and lymphoma, can also lead to oral manifestations, which are often the consequence of malignant cell infiltration or of accompanying thrombocytopenia and impaired immune cell function. The intraoral signs can be difficult to diagnose because they present clinical features that mimic other diseases such as periodontitis.

Impaired immune responses in general often lead to more significant oral inflammation and facilitate specific infection with pathogens. These infections, such as candidosis, can be mistaken for classic plaque-induced gingivitis or periodontitis. Lastly, this paper describes gingival pathology caused by certain medications, by vitamin deficiency as well as by local factors. All of these can cause gingival and periodontal lesions, which often resemble plaque-induced gingivitis or periodontitis. Commonly, plaque-induced and non-plaque-induced inflammations coexist in the oral cavity, leading to challenges in establishing a correct diagnosis of the primary underlying disease.

1. Cancer-related gingival lesions

1.1 Potentially malignant oral disorders

Potentially malignant oral disorders are a group of diseases that ideally should be diagnosed at an early stage. Oral leukoplakia, oral submucous fibrosis, and oral erythroplakia are the oral mucosal diseases that are most often considered to have a high malignant transformation rate (14-50%).2 Risk factors such as consumption of tobacco products, betel quid, alcohol, and diet as well as poor oral hygiene play an important role in development and/or progression.3,4 Infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) is recognised to be a major risk factor for oropharyngeal cancer and its precursor lesions but has only recently been recognised to play a role in the pathogenesis of oral epithelial dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma.5

Of the oral potentially malignant disorders, erythroplakia affecting the gingivae is the lesion most likely to be confused with gingivitis or periodontitis. Erythroplakia is defined as 'a fiery red patch that cannot be characterised clinically or pathologically as any other definable disease' (Fig. 1, Table 1). Both red and white changes in the same lesion may also occur (erythroleukoplakia). There remains some controversy regarding a clear definition of this lesion, and this is likely due to its rarity and the paucity of epidemiological data.6 However, some epidemiological data have been reported, which confirm erythroplakia as a rare entity.7 Erythroplakia is rarely multifocal and usually presents as a solitary lesion and this should alert the practitioner to the possibility of an alternative diagnosis.

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is another potentially malignant disorder. Although it does not mimic the appearance of gingivitis or periodontitis it commonly affects the gingivae and therefore should be included in this review due to its high transformation rate to squamous cell carcinoma, which has been reported in the range of 40-100%. It is characterised by multifocal verruciform (wart-like) white patches, often affecting the gingivae but not limited to this site (Fig. 2, Table 1). Its aetiopathogenesis is poorly understood but there may be an association with HPV-16 and -18, and Epstein-Barr virus. PVL appears to resist all therapeutic attempts and often recurs.8,9 Oral lichen planus(OLP)/PVL crossover or PVL arising in OLP, usually the plaque-like variant, has been reported, but this may simply represent a misdiagnosis of OLP at the first biopsy. Some authors have suggested that this may account for the malignant potential described in OLP.10

1.2 Lymphoma

The lymphomas comprise a heterogeneous group of cancers with diverse aetiologies, treatment pathways and outcomes.11 Oral cavity lymphomas represent the third most common malignancy in the oral cavity, surpassed by squamous cell carcinoma and malignancies of the salivary glands. Oral cavity lymphomas tend to be non-Hodgkin Bcell lymphomas, whereas non-Hodgkin Tcell lymphomas are rare in general and even rarer in the oral cavity. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) commonly presents as non-tender, enlarged lymph nodes, accompanied by diffuse symptoms of fatigue and low-grade intermittent fever. In 3% of cases (4% in patients with AIDS) the initial presentation can be in the oral cavity.12 A delay in diagnosis increases the morbidity and mortality of the condition. Primary intrabony sites can present as expansion of the mandible, enlargement of the mandibular canal and mental foramen, alveolar bone loss and tooth mobility. These signs may also be accompanied by swelling, pain, paraesthesia of the lip or pathologic fracture. However, NHL can present as oral mucosal swelling/hyperplasia and can therefore mimic other pathologic lesions including periodontitis, gingivitis, pericoronitis, apical radiolucencies or dental abscesses and is therefore difficult to diagnose (Fig. 3, Table 1).13

1.3 Leukaemia

Acute leukaemia is often accompanied by oral symptoms, which can be early manifestations of the disease. Oral complications such as gingival enlargement are more frequent in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) than in other types of leukaemia (Fig. 4, Table 1). Gingival enlargement in leukaemic patients is known to disappear on treatment of the underlying malignancy without any specific periodontal treatment. However, enlarged gingiva facilitates plaque accumulation and food impaction, and complicates oral hygiene practice, potentially leading to gingivitis with secondary gingival swelling.14

1.4 Squamous cell carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is among the commonest malignancies worldwide and accounts for the vast majority of all oral cancers. In South-central Asia, it is a common entity and the third most common type of cancer.15 Development of OSCC on the gingiva is seen in 10% of cases. These tumours commonly arise in edentulous areas, although they may also develop at dentate areas (Fig. 5, Table 1). It is generally agreed that carcinomas of the mandibular gingiva are more common than those of the maxillary gingiva and 60% of those are located posterior to the premolars. Although generally classified as a subset of OSCC, gingival SCC is a unique malignancy and can mimic a multitude of other lesions, especially those of inflammatory origin.16 Gingival squamous cell carcinoma (GSCC) is an uncommon condition of the oral cavity and shows a predilection for females.

1.5 Kaposi sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is the most common malignant neoplasm seen in AIDS patients. Malignant lymphoma and cervical cancer are two further AIDS-defining malignant neoplasms. Together, KS and non-Hodgkin lymphoma accounted for 99% of all AIDS-associated cancers before anti-retroviral treatment was introduced. Since this introduction, the incidence of KS has decreased in developed countries. Viruses that can alter mechanisms of apoptosis and cell cycle regulation, activate oncogenes, and inhibit tumour suppressor genes, such as Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus (also known as human herpes virus 8), are recognised as a significant contributing factor to the development of a variety of malignancies.17 KS is a multi-focal, angioproliferative neoplasm, it normally affects the skin and mucous membranes but can occur in the visceral organs. KS in its classic form is rare and not associated with AIDS, iatrogenic KS in immunosuppressed patients has also been reported. In AIDS associated KS initiation of anti-retroviral therapy is the mainstay of care upon which lesions normally regress but other treatment modalities including cryotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy may be required.18 In the oral cavity it presents as painless purpuric swelling often affecting the palate, gingivae, and alveolar mucosa (Fig. 6, Table 1).

Furthermore, a range of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can lead to a variety of oral lesions that may affect the oral mucosa including the keratinised gingiva in AIDS patients, these include aggressive forms of periodontitis.19

2. Specific infection-related gingival lesions

2.1 Fungal infections - oral candidiasis and oral histoplasmosis

Erythematous candidiasis is relatively rare and manifests as both acute and chronic forms. It is associated with the intake of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The chronic form is usually seen in HIV patients and only rarely involves the keratinised gingiva. It is the only form of candidiasis associated with pain.20 This disorder was previously thought to be directly associated with HIV, and it was therefore called HIV-associated gingivitis but has since been described in non-HIV infected individuals (Fig. 7, Table 1).

Histoplasmosis is a mycosis within areas of particularly high endemicity, mainly in countries of the African and American continents; however, it is very rare in Europe, where only imported cases are known.21 The aetiological agent is either Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum or Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii. It most commonly affects the lungs, but there can be systemic spread. Oral manifestations have been reported as the main complaint of the disseminated form of the disease and often lead the patient to seek medical assistance. Conversely, pulmonary symptoms may be mild or even misinterpreted as flu. Oral ulcerations and granulomatous tissue with bleeding are most commonly seen in this condition. Pharyngitis, dysphagia, odynophagia, and dysphonia can also occur.22

2.2 Specific bacterial infection

Bacterial infections can affect patients with and without immunodeficiency. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Treponema pallidum (syphilitic gingivitis), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (tuberculosis) and streptococci (acute streptococcal gingivitis) are the most common bacterial infections causing gingival lesions. These lesions can be associated with lesions elsewhere in the body.23,24 Neisseria gonorrhoeae can infect the oral cavity and the pharynx but it is normally sub-clinical and not associated with oral lesions. Pharyngitis is seen in less than 10% of cases with an oral infection. Although oral manifestations of tuberculosis rarely occur, they have been reported to appear in 0.1-5.0% of all TB infections. Oral manifestations of TB are re-appearing as a consequence of the emergence of antibiotic-resistant M. tuberculosis and of the higher incidence of AIDS. The oral tuberculosis lesions can be primary or secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis. The dorsum of the tongue is the most commonly affected site with these lesions appearing as a stellate ulcer, it can also present on the tongue as macroglossia; parotitis, tracheitis, and laryngitis have also been reported (Fig. 8, Table 1). Intra-osseous lesions, preauricular swelling and trismus may also be seen. Additionally, orofacial granulomatosis-like presentations caused by M. tuberculosis and atypical mycobacteria have been described.

3. Other causes

3.1 Drug-induced gingival overgrowth

Currently, the aetiology of drug-induced gingival overgrowth is not entirely understood but is clearly multifactorial, with age, sex, and duration and dosage of the drug being possible contributing factors. Medicaments that are associated with gingival overgrowth are cyclosporin, a potent immunosuppressant drug, as well as nifedipine, amlodipine (Fig. 9, Table 1) and several other calcium channel blocking agents. Other drugs potentially leading to gingival enlargement are phenobarbital and phenytoin and occasionally other anti-epileptic drugs.25

Interestingly, not all patients taking these medications develop gingival overgrowth. It has been hypothesised that these drugs decrease cellular folic acid uptake by gingival fibroblasts due to inhibition of cation transport. This leads to changes in matrix metalloproteinases metabolism and the failure to activate collagenase, which is crucial for the physiological degradation of accumulated connective tissue.26 Alternatively, local levels of tumour growth factor 1 beta in these patients have been reported to be a potential risk factor for developing gingival overgrowth.27 Cessation of the offending drug and both surgical and non-surgical periodontal care play a roll in management; however, it may not always be possible to stop or replace the drug in question.

3.2 Scurvy

Scurvy is the deficiency of vitamin C (ascorbic acid), which is infrequently encountered in modern industrialised nations. In developed nations scurvy most commonly occurs in lower socioeconomic groups, the elderly, and individuals who are institutionalised with diets devoid of fresh fruits and vegetables, and there is also an association with alcoholism, mental illness and chronic illness.28 Its incidence is unknown but it has been reported that the prevalence of adult vitamin C deficiency in the US was as high as 10 to 14% as recently as 1994.29 The lack of vitamin C leads to suppression and disturbance of collagen synthesis, resulting in degeneration of tissues and vascular walls. Oral scurvy is characterised by intense red, painful swollen gingiva that bleeds spontaneously on slightest provocation (Fig. 10, Table 1). The general discolouration that results from bleeding and blood breakdown is called scurvy siderosis.30 Scurvy is diagnosed by careful dietary history taking and serum ascorbic acid quantification and is treated with high doses of oral ascorbic acid. It is important to distinguish scurvy from acute presentations of leukaemia.

4. Local gingival irritation

Causes of local gingival irritation are not of a systemic disease nature, but rather related to psychological, habit and lifestyle, hormonal or anatomical factors. They are included in the following section, as they are often mistaken for plaque-induced gingival lesions, but require a differential therapeutic approach.

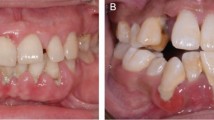

4.1 Mouth breathing

Inflammatory changes including gingival enlargement are frequently found in mouth breathers. This inflammation is thought to be due to alternate wetting and drying of the gingival surface, but increased plaque levels are also often found in these patients. A key feature is the presence of gingival enlargement in the maxillary and mandibular anterior regions (Fig. 11, Table 1).31 Mouth breathing may be due to anatomical reasons (short upper lip, proclined incisors, adenoids). In cases of bimaxillary dental protrusion, the gingival enlargement is typically limited to the palatal aspect of the maxillary incisors and the labial aspect of mandibular incisors.32 Other conditions that lead to dry mouth symptoms such as Sjögren's syndrome or radiation therapy can lead to gingival reddening and swelling; however, this is not restricted to the anterior teeth.

4.2 Injuries of the gingival tissues

Non-resolving lesions due to gingival injuries can be of accidental or intentional origin and can have a variety of clinical presentations (Fig. 12, Table 1). Chemical (eg aspirin, snuff, cocaine), physical (eg malocclusion, traumatic oral hygiene, partial denture, oral piercing, self-inflicted trauma) or thermal (hot beverages/food) injuries can have similar clinical features. Careful and sensitive history taking is necessary to identify the aetiology of such lesions. The management of gingival injuries include the elimination of the insult, symptomatic therapy, and possibly psychological intervention.33

Discussion

Systemic diseases can have a similar clinical presentation to periodontal diseases or exacerbate existing disease and vice versa. A variety of systemic diseases can affect the periodontal structures including immune mediated, autoinflammatory, hereditary, cancer related gingival lesions, infective and other causes. Additionally, there are a number of systemic diseases and conditions, which impact on the risk of developing gingivitis or periodontitis or on accelerating their progression. These are, for example, diabetes and pregnancy, but these conditions are beyond the scope of this series.

In cases where an alternative diagnosis is not immediately apparent, gingival inflammation should be addressed in the first instance by providing periodontal treatment according to the Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE; United Kingdom)/Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR; USA) scoring and guideline system, with emphasis on oral hygiene including Bass tooth-brushing technique and interdental cleaning with appropriate interdental brushes.34 Non-plaque induced gingival lesions are usually colonised and infected by oral bacteria, which can aggravate existing disease. Meticulous oral hygiene and individualised maintenance are essential to maintain gingival health and minimise the effect of the systemic disease to the periodontium. In cases of non-resolving gingival inflammation following successful periodontal treatment, careful examination of the oral cavity for additional mucosal changes may reveal findings indicative of an underlying systemic condition.35 Although effective oral hygiene and periodontal treatment are imperative to improve such lesions, the systemic disease should also be managed in the appropriate clinical setting.

The dental practitioner should be aware of the manifestations of systemic diseases to the periodontium and oral mucosa, however rare they may be, since the patient might have no other symptoms apart from the oral lesions. Indeed, many of the diseases discussed in these articles have a characteristic clinical presentation, which can alert the practitioner to the possibility of an underlying systemic disease. The authors hope that these clinically focused review articles will help practitioners in formulating a timely differential diagnosis that should facilitate appropriate and early referral, thereby aiding in the diagnosis and treatment of putative systemic disease.

References

Hirschfeld J, Higham J, Chatzistavrianou D, Blair F, Richards A, Chapple I. Josefine Hirschfeld. Systemic disease or periodontal disease? Distinguishing causes of gingival inflammation: a guide for dental practitioners. Part 1: immune-mediated, autoinflammatory, and hereditary lesions. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 961−966.

Yardimci G, Kutlubay Z, Engin B, Tuzun Y. Precancerous lesions of oral mucosa. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2: 866-872.

Rosenquist K. Risk factors in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Swed Dent J Suppl 2005; 179: 1-66.

Gupta B, Bray F, Kumar N, Johnson N W. Associations between oral hygiene habits, diet, tobacco and alcohol and risk of oral cancer: A case-control study from India. Cancer Epidemiol 2017; 51: 7-14.

Lerman M A, Almazrooa S, Lindeman N, Hall D, Villa A, Woo S B. HPV16 in a distinct subset of oral epithelial dysplasia. Mod Pathol 2017; 30: 1646-1654.

Holmstrup P. Oral erythroplakia - What is it? Oral Dis 2018; 24: 138-143.

Reichart P A, Philipsen H P. Oral erythroplakia - a review. Oral Oncol 2005; 41: 551-561.

Bagan J V, Jimenez-Soriano Y, Diaz-Fernandez J M et al. Malignant transformation of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia to oral squamous cell carcinoma: a series of 55 cases. Oral Oncol 2011; 47: 732-735.

Abadie W M, Partington E J, Fowler C B, Schmalbach C E. Optimal management of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 153: 504-511.

Garcia-Pola M J, Llorente-Pendas S, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Garcia-Martin J M. The development of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia in oral lichen planus. A preliminary study. Med Oral Patol Oral Bucal 2016; 21: e328-334.

Smith A, Crouch S, Lax S et al. Lymphoma incidence, survival and prevalence 2004-2014: sub-type analyses from the UK's Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1575-1584.

Silva T D B, Ferreira C B T, Leite G B, de Menezes Pontes J R, Antunes H S. Oral manifestations of lymphoma: a systematic review. ecancermedicalscience 2016; 10: 665.

Varun B R, Varghese N O, Sivakumar T T, Joseph A P. Extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the oral cavity: a case report. Iranian J Med Sci 2017; 42: 407-411.

Lim HC, Kim CS. Oral signs of acute leukemia for early detection. J Periodontol Implant Sci 2014; 44: 293-299.

Gupta N, Gupta R, Acharya A K et al. Changing trends in oral cancer - a global scenario. Nepal J Epidemiol 2016; 6: 613-619.

Markopoulos A K. Current aspects on oral squamous cell carcinoma. Open Dent J 2012; 6: 126-130.

Rubinstein P G, Aboulafia D M, Zloza A. Malignancies in HIV/AIDS: from epidemiology to therapeutic challenges. AIDS 2014; 28: 453-465.

Curtiss P, Strazzulla L C, Friedman-Kien A E. An update on Kaposi's sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther 2016; 6: 465-470.

Chapple I, Hamburger J. The significance of oral health in HIV disease. Sex Transm Infect 2000; 76: 236-243.

Williams D, Lewis M. Pathogenesis and treatment of oral candidosis. J Oral Microbiol 2011; 3: 10.3402/jom.v3i0.5771.

Bahr N C, Antinori S, Wheat L J, Sarosi G A. Histoplasmosis infections worldwide: thinking outside of the Ohio River valley. Curr Trop Med Rep 2015; 2: 70-80.

Brazão-Silva M T, Mancusi G W, Bazzoun F V, Ishisaki G Y, Marcucci M. A gingival manifestation of histoplasmosis leading diagnosis. Contemp Clin Dent 2013; 4: 97-101.

Holmstrup P. Nonplaqueinduced gingival lesions. Ann Periodontol 1999; 4: 20-31.

Jain P, Jain I. Oral manifestations of tuberculosis: step towards early diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: ZE18-ZE21.

Hatahira H, Abe J, Hane Y, Matsui T et al. Drug-induced gingival hyperplasia: a retrospective study using spontaneous reporting system databases. J Pharm Health Care Sci 2017; 3: 19.

Brown R S, Arany P R. Mechanism of drug-induced gingival overgrowth revisited: a unifying hypothesis. Oral Dis 2015; 21: e51-e61.

Wright H J, Chapple I L C, Blair F, Matthews J B. Crevicular fluid levels of TGFbeta1 in drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Arch Oral Biol 2004; 49: 421-425.

Velandia B, Centor R M, McConnell V, Shah M. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 1281-1284.

Hampl J S, Taylor C A, Johnston C S. Vitamin C deficiency and depletion in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1994. Am J Public Health 2004; 94: 870-875.

Japatti S R, Bhatsange A, Reddy M, Chidambar Y S, Patil S, Vhanmane P. Scurvy-scorbutic siderosis of gingiva: A diagnostic challenge - A rare case report. Dent Res J 2013; 10: 394-400.

Agrawal A A. Gingival enlargements: Differential diagnosis and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3: 779-788.

Taner T, Saglam-Aydinatay B. Physiologic and dentofacial effects of mouth breathing compared to nasal breathing. In Önerci TM (ed) Nasal physiology and pathophysiology of nasal disorders. pp 567-588. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2013.

Rawal S Y, Claman L J, Kalmar J R, Tatakis D N. Traumatic lesions of the gingiva: a case series. J Periodontol 2004; 75: 762-769.

British Society of Periodontology. Good Practitioner's Guide to Periodontology. 2016. Online information available at https://www.bsperio.org.uk/publications/good_practitioners_guide_2016.pdf?v=3 (accessed May 2019).

Armitage GC. The complete periodontal examination. Periodontol 2000 2004; 34: 22-33.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Elisabeth Reichardt at the Clinic for Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry, University Center for Dental Medicine, University of Basel, Switzerland (formerly at the Department of Orthodontics, Dentofacial Orthopedics and Paedodontics at Charité, Berlin, Germany); Dr Pravesh Kumar Jhingta at the Department of Periodontology, Himachal Pradesh Government Dental College and Hospital, Shimla, India and Dr Rajiv S. Desai at the Department of Oral Pathology, Nair Hospital Dental College, Mumbai, India for their permission to use clinical photographs. We further thank our patients for their consent to use their clinical photographs for this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH (Josefine Hirschfeld) and JH (Jon Higham) contributed equally to writing the mansucript and gathering demographic data for the table. JH (Josefine Hirschfeld) finalised the manuscript. FB, AR and ILC provided guidance and clinical photographs. All authors provided critical feedback.

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hirschfeld, J., Higham, J., Blair, F. et al. Systemic disease or periodontal disease? Distinguishing causes of gingival inflammation: a guide for dental practitioners. Part 2: cancer related, infective, and other causes of gingival pathology. Br Dent J 227, 1029–1034 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-1053-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-1053-5