Abstract

Both the dental health professional and the patient are responsible for the patient's failure to act on advice, the subsequent failure of treatment and worsening oral health. This paper looks at what can cause the failure and suggests various new ways of helping a previously non-compliant patient maintain their oral health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The word motivation is often used by dentists to describe their patients' non-compliance with recommended preventive actions. Colloquially motivation seems to refer to anything from the patients' lack of understanding, apparent inability to listen, to changing their health behaviours. It is as if the patient, like a naughty child, is being purposively irritating and is ignoring the advice being given. However, within this clinical scenario, no allowance is made for whether patients have the listening skills or the wish to change, or whether the clinician can listen, provide appropriate amounts of information and be patient enough to allow new health behaviours to become established. These important aspects of behaviour change are absent in discussions and complaints about disinterested and apparently unmotivated patients. It is the role of the dental health professional to assist patients to attain and maintain their oral health. In order to do so dentists must free themselves from any preconceptions or previous experiences of health education. Thus they can examine new ways to enable their patients to adopt and maintain oral health.

Advice-giving strategies for motivation and compliance

Most health education is given in the form of advice and the advice is usually given in the form of knowledge. It has been assumed that by providing knowledge there will be a modification in attitude which will result in behaviour change. The advice model of health education (KAB)1 is based upon the idea that by increasing patient's awareness of the severity and threat of the disease (the cons) together with the benefits of complying with the recommended preventive actions (the pros) will result in a lasting behaviour change.1 Essentially, this model proposes that patients can move from a state of being unaware of the need to change to a state of complete compliance with the recommended actions. However, the advice approach to motivating patients is flawed.2 The problem with giving advice is that, although there may be some short-term benefits, for the most part the advice is largely ignored. The limitations of the advice strategy include the behavioural aim of the intervention, the methods used, the time given for imparting the information, the inertia of mental life (resistances) and the ambivalence or disinterest on either the dentist's or patient's part.

In general practice dental health professionals use advice to help to persuade their patients to adopt preventive actions. Patients hear the advice as critical and intrusive. The patients' resistance to change is increased and unhealthy behaviours reinstated.3 Dental health professionals, sensing that their words are ignored, feel that dental health education is a waste of time. Brief advice interventions thus end in impasse with patient and dentist retreating to previously held positions with respect to dental health education and the adoption of preventive actions.2,4,5

Patient-centred strategies for motivation and compliance

How can dentists enable their patients to adopt and maintain preventive health behaviours? First, it is clear that whatever strategy is to be used it must incorporate some means of providing information other than in an advice-giving format. Secondly, rather than the information being given like a prescription for some dreadful medicine, it must be presented in such a way that patients feel that it is important to them and that they can, so to speak, take ownership of it. In other words patients, within the equality of the dentist–patient relationship, can take co-ownership of the health education interaction and in doing so acknowledge their readiness to change. In such participative interactions, motivation can be perceived quite differently with patients' readiness to change acting as the key factor in promoting health skills. Readiness to change, can provide a bridge between the health care professional and patient with respect to understanding patients' lack of motivation to change their health behaviours.

Bringing about lasting and effective changes in health behaviours is not about being prescriptive but it is about participation. It is about encouraging patients to identify and express their own dental health needs, exploring their own attitudes and values as well as empowering them to make any necessary changes in their own lives. At the centre of the success of one-to-one health education is yet another partnership. This partnership is three-way. It is between the dental health professional, the patient and time. For all concerned, lasting and effective changes in health behaviours are dependent on time. The role of the health professional is to identify which patients are ready to change, and to provide them with the appropriate help and support to enable them to do so. By doing so the health professional's time can be most effectively employed, not only by enabling patients who are in a state of readiness, but also by offering other patients, who are still ambivalent, time to become ready for change. There are two procedures which are important in this regard. These are first a patient-centred technique known as motivational interviewing2,4,5 and secondly, a framework for health actions known as the stages of change model.6,7 Using a combination of these procedures allows dental health professionals together with their patients to accept mutual responsibility for oral health.8 At the same time it provides the health professional with the opportunity to appreciate that change is a slow and gradual process from unawareness through motivation to compliance.

Procedures important for patient motivation

-

Motivational interviewing

-

Stages of change model

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing as a patient-centred technique encourages patients to speak and by doing so enables them to identify their oral health needs. The health professional acts as a catalyst only intervening when necessary thus allowing patients to recognise internal resistances reflected in lifestyle barriers. It is during this initial period that the health professional starts to assess patients' ambivalence, conflict and readiness to change.

In practical terms the health professional must have a series of ground rules. These are first a fixed length of time for the appointment, secondly, to take time to explain to patients what is to happen during their times together and thirdly, to provide an environment in which patients feel able to speak, question and discuss the priority of their oral health needs. Some patients can speak freely whereas others find it difficult to start but with encouragement can overcome their reticence. However a third group exists who find it impossible to articulate their feelings. For such people the use of an 'agenda-setting chart' is essential5 (Figure 1). The chart sets out a series of visual images of, for example, dental health actions for discussion. Patients choose (from the pictures) or suggest various options (as represented by the query in the blank circle) which they feel are most important to promote their oral health (Figure 1). In this way patients identify their own dental health goals and negotiate the time for change. Readiness to change now becomes a vital part of the process and can be assessed visually using the readiness to change ruler. This scale runs from 'not ready' through 'unsure' to 'ready'.

The motivational interviewing technique together with assessments of readiness to change, enable patients to develop their own agenda and health goals. Irrespective of whether patients feel they wish to start or not the emphasis of the motivational interview is on the individual patient. Patients' awareness of their feelings, conflicts and opinions will allow an identification of their own health goals while acknowledging their wish to change. If this is the right time for change then a personalised preventive regime may be negotiated. However when a patient is 'ambivalent' or 'not ready' then the health professional must wait. The oral health agenda and the speed of change from unawareness to compliance belong not only with the health professional but with the patient. Therefore patients in partnership with the health professional place in motion the beginnings of their behaviour change.

Increasing awareness within a patient- centred exchange may be all that is necessary to enable a mother and child to change from unhealthy to less unhealthy behaviours. In the following example the dentist had to negotiate with the mother while acknowledging mother's fears that she had caused her daughter's dental decay. In this difficult situation the dentist had to allow the mother to state her fears. Giving advice at this point in the exchange as outlined in Case 1 would have resulted in conflict and impasse.

Case 1 Jane is a pretty three year old. Jane and her mother attended after Jane had a general anaesthetic to have her deciduous incisors extracted as a result of bottle caries. Jane was quite unaffected by the strange surroundings and lay quietly on mother's lap to have her teeth examined. Jane had a number of small carious lesions and so the issue of prevention needed to be addressed, in particular Jane's diet. Gently the dentist asked about it. Mother admitted that Jane was a poor eater and they had gotten into the habit of putting her to bed with 'juice'. Mother feared she was to blame, 'The juice could not have caused this it is pure — no sugar — Jane cries if she doesn't have her juice...it's difficult to get her down at night'. Mother wanted to know how she could prevent Jane having further problems with her teeth — she was ready to change. However a conflict situation still existed which needed to be addressed. Although Mother recognised the need to prevent tooth decay she feared the difficulties she would experience if 'juice' were removed as a bed-time and night-time drink. A solution to the problem of dental caries prevention had to be devised within the wider context of home life — that is an achievable rather than an ideal solution had to be negotiated as an interim health goal. Mother felt that Jane would tolerate a bed-time drink of milk and she would put water in the dinky cup if Jane needed a drink in the night. This solution worked with little disruption to home life. Gradually night-time drinks became unnecessary and fluoride supplement use was included in the next phase of this patient-centred preventive programme.

During the initial interview the dentist realised that Jane's mother was motivated. Mother had already thought about the reasons for her daughter's tooth decay. She had weighed up the pros and cons of removing juice as a bed-time and night-time drink and had decided that something had to be done and she was ready to change. With support from her partner at home mother was able to establish and maintain a new preventive regime for her daughter. How can dental health professionals be confident of their assessments of where their patients lie on an unawareness-compliance continuum? Such evaluations are necessary if dental health professionals are to negotiate, implement, re-negotiate and understand difficulties their patients experience when complying with preventive regimes.

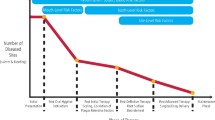

Prochaska and DiClemente6 devised a model for this eventuality. They called it the 'stages of change model'. The model is divided into six different stages of behaviour change. These are precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance and relapse. The stages reflect and hence provide a means of assessing progress from unawareness (precontemplation) through motivation (contemplation, preparation) to compliance (action, maintenance). The stages are based upon measures of readiness to change which include the degree of ambivalence, the resolution of conflict, as well as the establishment and maintenance of the health behaviours. Thus progress through the stages is slow and torturous with many false starts and relapses. People with chronic dental problems cannot jump from precontemplation to maintenance nor can they progress in an orderly fashion from one stage to the next. Their behaviour change is characterised by forward and backward movements with progress from precontemplation to maintenance being a spiral rather than a simple linear advance.6,7

The stages of change model

The stages of change model can assist dental health professionals in their work with patients. It provides a framework by which they may evaluate their patients' progress from unawareness through motivation to compliance. This section describes each of the stages in detail. Clinical illustrations from practice are presented. These clinical examples demonstrate the usefulness of this technique in motivating patients to establish and maintain new health behaviours.

Prochaska's 'stages of change' model

-

Precontemplation

-

Contemplation

-

Preparation

-

Action

Stage 1: Precontemplation.

Precontemplation is characterised by patients being made aware of the need to change their health behaviours. It is at this stage that motivational interviewing as a technique is used to assess ambivalence and readiness to change. The need to acknowledge patients' ambivalence, concerns, anxieties together with their wish to change provides the dental health professional with the opportunity to set out the pros and cons of changing.9,10 The discussion of the pros (dental health education) together with the identification of the cons (barriers) provides the basis of the precontemplation stage. Interventions used at this time must include providing patients with health information as well as the dental health professional discovering lifestyle difficulties which might act as barriers and resistances to progression to the next stage. Changes in personal health status, at this early time can act as a catalyst for progress. This was so, in the case of Mr I (Case 2) who had recently been diagnosed with maturity onset diabetes mellitus.

In this example Mr I's impetus for changing from precontemplation to contemplation was his overall physical health. Using motivational interviewing the pros and cons of changing were discussed, not only in relation to his dental health status but also in relation to his overall health. Gradually Mr I was able to move into the next stage of change.

Case 2 Mr I is a 75 year old widower. At a routine appointment the dentist noted that he had secondary caries affecting a number of his restorations. Mr I was referred to the dental hygienist for dental health education. Discussions as to why these lesions had developed took place. Since the death of his wife Mr I had never really 'got into the way of cooking'. He got hot meals from meals-on-wheels and survived the rest of the time on sweet cups of tea with cakes and biscuits. He told the hygienist that he had been diagnosed as being diabetic but it was being controlled by diet. The hygienist using this information linked Mr I's carious teeth to his sugary snacking pattern and related it to his overall health. A preventive plan was negotiated in which the sugar was to be replaced by an artificial sweetener and the biscuits or cakes by an easily made sandwich. The hygienist continued to see Mr I. As part of his continuing care she encouraged Mr I to consult the dietician at his doctor's practice.

Stage 2: Contemplation

In this stage the patient is thinking about the pros and cons of changing. The pros and cons usually have equal importance and this is illustrated in the above example of Mr I. Once provided with the necessary information and his preventive strategy Mr I had to decide, to think and to contemplate what to do next. However difficulties are often encountered during this stage.11,12 Many patients become stuck and while the pros of changing may outweigh the cons, moves to the next stage of preparation simply do not happen. These individuals have been described as 'chronic contemplators'.11,12 Such patients are regularly seen in practice. Often children in particular can be described as chronic contemplators because although the cons of eating cariogenic snacks outweigh the pros, they are unable to give up the pleasure of their carbonated drinks, confectionery, cakes and biscuits. However the example given here is of Mr C a 35 year old married man (Case 3). He seemed unable to brush his teeth effectively even after many years of oral hygiene instruction.

Case 3 Mr C is an example of a chronic contemplator. His gingival condition was poor and his plaque scores high. Although he had attended the hygienist on many occasions and felt somewhere in himself that it was important to brush his teeth he seemed unable to put this thought into action. Nevertheless the hygienist continued to provide support and encouragement. She video-recorded Mr C while tooth-brushing believing if she gave him an active role in his prevention, he would gradually understand what he was being asked to do. He would change as she had seen others do before.

Stage 3: Preparation

Although many clinicians would have given up with Mr C, it seemed that the hygienist, recognised the need for a preparation time prior to Mr C being able to move into action. She felt that he needed constantly to hear the pros and cons of changing as well as participating in oral hygiene activities.8 Cases of chronic contemplators seem to be helped by repeatedly hearing the pros and cons of changing. They are supported, encouraged and prepared for action by participating in their preventive programmes. For Mr C this meant being video-recorded while brushing his teeth. Preparation time improves self-awareness and self-image, increases readiness to change and helps in reducing the patient's ambivalence and conflict.9,10,11,12 The need for a prolonged preparation stage seems to be essential for chronic contemplators. However their apparent lack of motivation and compliance may lead to disillusionment on the part of the dental health professional.

Stage 4: Action

By the time patients have reached the action stage they have resolved their conflict. It is as if a 'cross-over' has occurred and the pros of changing now outweigh the cons. There is the need to support the patient through these early days since the newly acquired behaviour will be subject to every possible influence -- both positive and negative (Case 4).13

Case 4 Jim is 15 years old. He is quite frightened of dental treatment and this anxiety has provided the impetus for Jim to restrict sugar to mealtimes. His mother has provided the main support for his actions. However, recently he has found it difficult to comply with his preventive programme. He plays football for the school team and after training or a match was thirsty and hungry. He feels constrained by his team-mates and so usually joins them for a fizzy drink and sugary snack. It seemed like there was no way out of this difficult situation and so it was decided to retreat to the contemplation stage. The pros and cons of using sugar-free drinks and less cariogenic snacks was discussed. It was decided that he would try this option when he was next faced with peer group pressure. This interim solution has worked. All involved recognise its limitations.

Jim's problem in complying with his preventive regime was related to his wish to 'fit in' with his peers. It was necessary to find a solution — a compromise — and this meant retreating to the contemplation stage. The compromise solution allowed Jim to 'fit in' without his actions being entirely detrimental to his dental health status. This example illustrates the need to re-negotiate health goals as well as focusing prevention upon Jim's psycho-social needs. In this way, although the compromise health goal may not be ideal, it will be attainable and appropriate for the individual at that point in time. After all, 'health goals [are] staging posts on the way to the final destination of positive health behaviours'.14

Case 5 Mrs F had recently had her last child. She was in her early 40s and this had been a second pregnancy within three years. She was shocked to learn that she had experienced considerable bone loss during the intervening three years. Her oral hygiene was good and she was at a loss to know how this could have happened. Discussions concerning the need for periodontal treatment on the one hand and need to maintain a rigorous level of personal oral hygiene on the other provided the opportunity to re-negotiate health goals based upon mutual participation. At this point in the intervention there was a retreat to contemplation and to preparation stages. During the preparation stage Mrs F was shown how to improve her oral hygiene using dental tape and an inter-dental brush. Periodontal care was provided. She was given support during this period in order to allow these new oral hygiene routines to become established.

Stage 5: Maintenance

Using the strategy as suggested in Case 4 enabled Jim to maintain his behaviour change. Although Jim was on the verge of relapse, using the stages of change provided all concerned with the opportunity to re-group and re-negotiate Jim's preventive programme. It is important that the intervention reflects the stage of change the patient has reached. Patients who have reached the action and maintenance stages benefit from shorter, more intensive and more participative interventions. They have taken responsibility for their oral health while acknowledging the supportive role of the dental health professional. Once action and maintenance have been reached the interventions must be 'mutually-participative' reflecting the joint responsibility for maintaining oral health improvements (Case 5).8

Stage 6: Relapse

Relapse occurs when maintenance strategies breakdown and previous unhealthy behaviours are resumed. Although this stage is common and may appear as a disaster it provides an opportunity for re-grouping and re-negotiation of health goals. It appears that patients in the relapse phase may return to the contemplation stage but progress quickly through preparation to action.14 Relapse allows patients to recognise that what they have achieved once they will achieve again. The need for the health professional to be supportive and re-negotiate more realistic, achievable goals allows the patient's doubts to be expressed and conflict-changing to be resolved. According to Jacob and Plamping:14

The challenge...at the relapse stage is to be supportive and accepting...to aid the patient...re-enter the action stage rather than blaming her...this has the effect of returning the patient to the precontemplation or contemplation stages, where she may question if she really wants to change anyway!

Case 6 Kate is an attractive 16 year old. Recently there has been an upsurge of caries activity. She has areas of decalcification between her upper incisors and bite-wing radiographs show interstitial lesions on the premolar and molar teeth. It was clear that something has changed in Kate's diet. She was unaware that she was snacking more than usual and was angry at the implication. She had been sticking to the negotiated plan. The hygienist recognised Kate's fears that she was being blamed and so took an alternative approach — she discussed with Kate her concerns about the need for anterior restorations. Kate had an attractive smile 'it would seem a shame if she needed to have fillings in her front teeth'. Using this health-related approach enabled Kate to discuss her diet. It occurred to Kate that she had been sucking mints while studying for examinations — 'it cuts the boredom and helps me concentrate'. The effects of the mints upon Kate's teeth were discussed together with a series of sugar-free alternatives including sugar-free chewing gum. It was agreed that Kate would return to using a fluoride supplement at night. Kate was seen several times during the summer period following her examinations. The sweet eating had stopped. The hygienist's concerns about how easily Kate had relapsed were discussed with the dentist. It was decided that there was need for continuous monitoring of Kate's compliance as an integral aspect of her oral health care.

The example of Kate (Case 6) illustrates Jacob's and Plamping's concerns. Kate feared criticism and as her ambivalence increased, her readiness to change decreased. Hence there is the need to use alternative strategies. In this case a health-related approach proved fruitful. Appealing to the importance of Kate's appearance reduced Kate anger and ambivalence. This allowed Kate to appreciate the importance of changing her health behaviour.

Conclusions

There is the idea that it is easy for patients to change their health behaviours. All that needs to be done is to give health information and patients will change. However this disregards the inertia of mental life and the difficulties people have in changing. Many people feel ambivalent about the idea of changing since it means having to give up things which provide them with pleasure and enjoyment. If the conflict patients experience in trying to change is to be resolved then dental health professionals need to use patient-centred interviewing techniques to help them. Using motivational interviewing allows patients to explore their attitudes to both the cons (costs) and the pros (benefits) of changing as well as allowing the dental health professional the opportunity to assess their readiness to change. The patients' position on the unawareness-compliance continuum can then be assessed using the stages of change model.6,7,79,10,11,12 This dynamic framework provides a reassurance for the health professional since it demonstrates that people can progress as well as regress through the stages.

Motivating patients to change their health behaviour is a complex issue which relies upon the understanding and patience of health professionals. By using motivational interviewing together with the stages of change model, dental health professionals can facilitate behaviour change in their patients, as well as enabling them to achieve the long-term health goals of compliance with maintenance of their newly, secured health actions

References

Rosenstock I M . What research in motivation suggests for public healt. Am J Pub Hlth 1960; 50: 295–301.

Rollnick S, Kinnersley P, Stott N . Methods of helping patients with behaviour change. Brit Med J 1993; 307: 188–190.

Baric L . Social expectations versus personal preferences - two ways of influencing health behaviour. J Inst Hlth Educ 1977; 15: 23–27.

Butler C, Rollnick S, Stott N . The practitioner, the patient and resistance to change: recent ideas on compliance. Can Med Assoc J 1996; 154: 1357–1362.

Stott N, Rollnick S, Rees M, Pill R . Innovation in clinical method: diabetes care and negotiating skills. Family Practice 1995; 12: 413–418.

Prochaska J O, Diclemente C C . Stages and processes of self change of smoking: toward an intergrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1983; 5: 390–395.

Diclemente C C, Prochaska J O, Fairhurst S K et al. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1991; 59: 295–304.

Blinkhorn A S . Factors affecting the compliance of patients with preventive dental regimes. International Dental Journal 1993; 43: 294–298.

Prochaska J O . Assessing how people change. Cancer 1991; Supplement 1: 805–807.

Prochaska J O . Why do we behave the way we do. Can J Cardiol 1995; 11 Supplement A: 20A–25A.

Prochaska J O, Velicer W F, Rossi J S . et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviours. Health Psychology 1994; 13: 39–46.

Velicer W F, Hughes S L, Fava J L . et al. An empirical typology of subjects within stage of change. Addictive Behaviours 1995; 20: 299–320.

Brownwell K D, Cohen L R . Adherence to dietary regimens 2: components of effective interventions. Behavioural Medicine 1995; 20: 155–164.

Jacob M C, Plamping D . The practice of primary dental care. London, Wright, 1989.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freeman, R. Strategies for motivating the non-compliant patient. Br Dent J 187, 307–312 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800266

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800266