Key Points

-

As far as possible spend time preparing for difficult communication situations, giving consideration to the information given, the setting and time constraints

-

When breaking bad news try to explore the patient's view of the bad news, work with the patient to determine the way forward

-

Consider training a member of your dental team in counselling skills

-

Take time to review difficult communication situations. Consider what went well, and what could be improved.

Abstract

During their professional career most dental practitioners will be faced with a situation in which they have to break 'bad news'. This article examines the communication skills involved in breaking bad news to patients. The process is broken down into three broad stages: preparation; discussing the information; and reviewing the situation. Within each of these stages specific and practical recommendations are given. The importance of recognising the impact which such interactions have upon the dental practitioner is emphasised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The quality of dentist-patient communication is a key determinant of patient satisfaction with consultations and of patient participation in, and compliance with, therapeutic planning.1,2 Breaking bad news is one of the most difficult tasks which any healthcare professional has to undertake, but one which many dental practitioners will face. The nature of 'bad news' will vary with the type of work which the practitioner routinely performs, and according to the patients, he or she sees. The situations in which dental staff may have to break bad news are numerous. For example you may have to:

-

Tell patients that you have found a suspicious lesion which requires investigation

-

Inform patients that they are going to lose all their teeth

-

Inform patients that they require surgery to remove a lesion

-

Discuss with patients that you have observed an oral condition suggestive of a systemic illness.

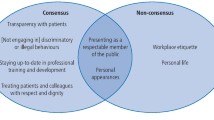

While it seems likely that practitioners will agree that certain information and news which he gives to patients is 'bad news', it is important to remember that its meaning may be significantly worse to the patient than the meaning ascribed to that information by a dental health professional. What constitutes 'bad news' has an element of subjective judgement. For example, the work of Fiske, Davis, Frances and Gelbier showed effectively the great impact which tooth loss can have.3 Our intuitive sense of the impact which should be experienced in regard to a certain situation may not be an accurate reflection of the actual impact experienced by the patient. It is important to note that 'bad news' for patients may differ from the perspectives of those who are accustomed to dental disease. The importance of accurate empathy in effective dentist-patient communication has been suggested by a number of researchers.4,5,6

The extent of the impact that bad news has on an individual is most often dependent on the way in which such information is communicated. Research from the fields of cancer and maternity care consistently show that the way in which 'bad news' is communicated is just as important in determining the individual's long term adaptation to it as is the content of the message itself.7

Despite a body of literature which has examined physicians' skills in breaking bad news, there exists little published dental literature in this area. In this paper we explore the literature on medical communication and discuss some of the considerations which apply when breaking bad news. We outline three important components to breaking bad news based upon the work of Davies and Newton.8 These are:

-

1

Preparation. This involves thinking about the situation and as far as possible identifying strategies for dealing with it.

-

2

Discussing the situation. This is the process of communicating with the patient the news. It requires both general and specific communication skills.

-

3

Reviewing the situation. This allows the practitioner to identify what went well and what went less well in the situation. It is also important in reviewing the situation to identify that breaking bad news is difficult and inevitably has an impact on the person who is breaking the bad news.

These three components occur in sequence (fig. 1).Careful preparation for each component can help the process of breaking bad news.

The preparation phase

This involves, whenever possible, ensuring that the breaking of the bad news takes place in an atmosphere and a setting which is comfortable and safe for the patient. In preparing for breaking bad news three areas should be considered:

-

1

The information to be given

-

2

The setting of the interaction

-

3

Time considerations.

The information to be given

It is important that you have as much information to hand as possible, even if not all of this information is given to the patient. Usually you will have the information available as part of your knowledge and experience. When giving a patient information they may not hear everything you are saying and it may be useful to provide them with written material to support the message which they can refer to later. Drawings and illustrations can also help to reinforce the message. The design of written materials requires careful consideration if they are to be of value to patients. They should be clearly written and understandable. Newton described the characteristics of written materials which are most beneficial to patients.9 These are:

-

Clear and legible text. Text should be of an adequate size and clearly printed

-

Clear and understandable writing. This is usually assessed as the readability of the text

-

Avoidance of the use of technical language or jargon which the patient may not understand.

The setting of the interaction

In general, the patient will feel most comfortable in discussing issues if the setting helps to foster a relationship of equality with the dentist. This may include: the dentist and patient sitting at the same height, the distance between the two parties being not too far apart; and both parties sitting on the same type of chair. You may like to consider moving from the dental chair to a place where both dentist and patient can sit on chairs by a desk.

Privacy is important. The patient wants to feel that there is the space and opportunity to talk about the news without fear of interruptions or of being overheard. Privacy excludes the possibility of interruption so that the dentist should ensure that there is no possibility of telephones ringing; other staff entering the room; or if the surgery is the venue, of dental nurses carrying on with their work. In discussing privacy it is important also to consider the need for a chaperone, if the practitioner feels that it is important that one is present the patient could be asked to bring an escort or accompanying person. Alternatively another member of the dental team could be asked to sit in.

Timing

The dentist needs to allow sufficient time for giving information and exploring the patient's response. This can be very difficult when there has been little time for preparing for the breaking bad news situation, or when you are working in a busy practice or clinic. If you can anticipate having to break bad news to a patient, then perhaps it is best to book a double appointment or perhaps an appointment at the end of the clinic or patient list. When there is no time to prepare for breaking the bad news, for example informing a patient who has attended for a routine check-up that they are going to lose a tooth, you may wish to consider offering an early follow-up appointment acknowledging to the patient the limited time available and the importance of discussing the matter further. It is useful to let the patient have an idea of the time available, particularly where this may be restricted, by saying for example, 'We have 20 minutes today'. Also the dentist can warn the patient when their time is nearly finished, 'We have 5 minutes left today'.

The dentist should also consider the timing of the appointment from his own perspective as well as that of the patient. What other stresses are present at that time, and how these might affect his or her own reaction to the consultation.

Discussing the news

In discussing the bad news, there are four main steps:

-

Initiating the discussion

-

Exploring the patient's view of the bad news

-

Deciding on the way forward

-

Summarising and closing.

Initiating the discussion

Garg, Buckman and Kason have suggested the following steps should be followed:10

-

1

Find out what the patient already knows

-

2

Find out what the patient wants to know

-

3

Give information

-

4

Respond to the patient's reactions.

As a first step in delivering bad news to a patient it is useful to identify the patient's current knowledge and expectations about their health. This can be achieved by asking the patient what he or she already knows or suspects, using, for example, sentence frames such as: 'What have you made of all this?' 'What have you been told?'

In identifying the patient's level of knowledge the dental practitioner is also attempting to ascertain the patient's level of comprehension, the kind of vocabulary he uses in understanding his situation and any coping strategies he may be adopting such as denial. The next step is to find out what the patient wants to know. It is possible that the patient may only want very limited information at this initial stage. Try to obtain a clear invitation to share information if this is what the patient wants. Useful questions for ascertaining the extent of information giving which the patient desires are: 'Are you the sort of person who likes to find out everything, or Do you prefer a little information at a time ?', 'Would you rather talk about it all now, or would you like to go away and think about it a little first ?'

In giving the information, two processes are important: aligning and educating.11 In aligning the clinician starts at the level of the patient's comprehension and attempts to use the same vocabulary in breaking the bad news being careful not to sound patronising or condescending. The process of educating involves giving information in small chunks, using simple language and checking regularly to ascertain whether the content is understood. Immediately after giving the news allow some time and, possibly, moments of silence while the patient comes to appreciate the facts.

The reactions of patients to receiving bad news can be extremely varied ranging from emotional expression such as crying and anger to emotional inexpression such as silence — for example, the patient who is 'struck dumb' by the news. It is important to acknowledge all reactions and feelings. A useful technique in this regard is the empathic response technique outlined by McLauchlan which recommends identifying the emotion and the cause and responding to show the patient that this connection has been made.12 For example, a patient who has been told at a routine appointment that a white patch has been discovered and that it requires an investigation may be dumbstruck; the dental practitioner can respond to this by identifying the emotion and its cause, 'This must be a shock to you. You probably didn't expect this at a routine appointment'.

Dealing with crying and with anger and other strong emotions is a challenge for all healthcare professionals.13 The important skills to learn are to allow the emotion and to accept it. It may be difficult for patients to show emotions, generally the expression of strong emotion is controlled. By allowing the emotion and not appearing to judge the patient for it, the clinician shows acceptance of the patient's feelings. Listening to the patient is important here. Avoid platitudes such as: 'It happens to the best of us' and false sympathy such as 'I know what it's like', as these will usually elicit an angry response. Instead your responses should show empathy — an understanding and acknowledgement of the feelings which the patient is expressing 'It must be very hard for you ...' or 'It must come as a real shock ...' Patients may also find it comforting to be given some idea of the impact that the news has had upon you, for example you may wish to say, 'It's difficult for me to tell you this' or 'I haven't found this easy'.

Exploring the patient's view of the bad news

The patient's view of the bad news and his understanding of it can have a major influence upon adjustment to the news. Was the news expected or unexpected? This may have emerged in earlier discussions when the clinician tried to ascertain the patient's current understanding of the situation. It is important to recognise that even if the news was expected, the patient may have been hoping for the faint possibility of good news. The clinician should explore the fears and fantasies which the patient has concerning the news he has been given. What is he expecting to happen? What does he imagine to be the best and worst case scenarios?

Deciding on the way forward

The clinician and the patient should work together to decide on a plan of action and a way forward. There is considerable evidence from both the dental and medical literature to suggest that patients involved in planning their own treatment are more satisfied with their interactions with a healthcare professional, and are more likely to comply with the treatment recommendations.14,15 In deciding on the way forward at least three things need to be identified: the nature of any future treatment, follow-up appointments, and the nature and extent of support which the patient can access.

Early follow-up is usually preferable following the receiving of bad news, perhaps within a week. The patient may not process much information after he was given the bad news. The period of time between the appointment in which he was given the bad news and the follow-up gives the patient the opportunity to reflect on the news and to identify questions which he would like to ask. It also provides the opportunity to assess the patient's adjustment to the news.

The clinician should identify the range and extent of the patient's support networks. Who will the patient talk to? Is there anyone who can spend time with the patient? Who is their closest confidante, and how easy or difficult is it for the patient to contact them? Are the barriers to talking to other people more than just physical? Some patients may not feel that they can talk to their partners about potentially distressing news. The clinician should concentrate on identifying not only who the patient can talk to, but also what he can talk to them about. In some instances it may be appropriate to provide information about self-help groups or counselling services.

Summarising and closing

In breaking the bad news, the clinician has achieved a great many tasks and covered a great deal of information. The aim of the end of the consultation is to bring together all this information in a brief and coherent summary. It identifies to the patient the logical progression from the situation before the interview, how this is affected by the information given, and the directions for the future. Part of this will be giving information about the arrangements for follow-up. Finally, you may feel it is important to give the patient some contact telephone numbers in case he has questions or requires clarification. You should give careful thought to which numbers the patient is given. It is important to strike a balance between the patient being able to contact someone, and the possibility that the patient may contact you at a difficult time. The clinician needs to think about his own availability to patients and when and where he would feel comfortable talking to a potentially very distressed patient. It is unlikely that you would want patients to contact you at home for instance. An alternative approach to providing a point of contact is to consider training a member of your team in counselling skills. Courses in counselling are widely available. The British Association of Counselling will provide further information on courses in your area (the address is given below).

Reviewing the situation

Giving bad news to someone is very difficult. Inevitably it draws on your emotional resources. It is important to take the time to review how the consultation went. The first part of the process is to acknowledge the impact that the consultation has had, and to talk to someone about this. The process of discussing the impact which a difficult situation has had upon us is cathartic. It provides the opportunity to offload some of the feelings that arise in difficult situations. Finally, the consultation can be viewed as an opportunity to reflect on what went well; and what, perhaps, you might do differently should a similar situation arise again.

If you find that, as a clinician, you are often in the position of breaking bad news to patients, you may wish to consider setting up some form of structured support mechanism. This might take the form of regular meetings with a person with whom you can discuss your work and the issues that arise with patients. Ideally this person should be trained in counselling and not intimately connected with you or the practice. The confidential nature of any information should be recognised, particularly when sharing information about patients.

Breaking bad news is difficult. It raises emotional issues for patients and, potentially, dentists. The key steps are: preparation, discussing the information, and reviewing the situation. As far as possible you should prepare how you will break the news, including the information to be given and the manner in which it will be given. Good preparation should make the process of discussing the information easier, but it is never simple. Acknowledging these difficulties is an important step in reviewing the situation, as is acknowledging the impact that the bad news has had on yourself and your patient.

References

Sondell K, Soderfeldt B . Dentist-patient communication: A review of relevant models. Acta Odont Scand 1997; 55: 116–126.

Newton T . Dentist/patient communication: A review. Dent Update 1995; 22: 118–122.

Fiske J, Davis D M, Frances C, Gelbier S . The emotional effects of tooth loss in edentulous people. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 90–93.

Jackson E . Establishing rapport. I. Verbal interaction. J Oral Med 1975; 30: 105–110.

Jackson E . Convergent evidence for the effectiveness of interpersonal skill training for dental students. J Dent Educ 1978; 42: 517–523.

Levy R L, Domoto P K, Olson D G, Lertora A K, Charney C . Evaluation of one-to-one behavioral training. J Dent Educ 1980; 44: 221–222.

Maguire P, Faulkner A . How to do it. Communicate with cancer patients: handling bad news and difficult questions. Br Med J 1988; 297: 907–909.

Davies M, Newton J T . Breaking bad news. In Careful communication. Brussels: University Catholique de Louvain, 1995.

Newton J T . The readability and utility of general dental practice patient information leaflets. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 329–332.

Garg A, Buckman R, Kason Y . Teaching medical students how to break bad news. Can Med Assoc J 1997; 156: 1159–1164.

Buckman R, Kason Y . How to break bad news – a practical protocol for healthcare professionals. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

McLauchlan C A J . ABC of major trauma: handling distressed relatives and breaking bad news. Br Med J 1990; 301: 1145–1149.

Buckman R . Breaking bad news: Why is it still so difficult? Br Med J 1984; 288: 1597–1599.

Lefer L, Pleasure M, Rosenthal L . A psychiatric approach to the denture patient. Psychosom Res 1962; 6: 199–207.

Roter D . Which facets of communication have strong effects on outcome — a meta-analysis. In M Stewart & D Roter (Eds) Communicating with medical patients. Newbury Park, Sage.

Acknowledgements

Address for the British Association for Counselling: The British Association For Counselling, 1 Regent Place, Rugby CV21 2PJ Tel: 01788 578328

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newton, J., Fiske, J. Breaking bad news: a guide for dental healthcare professionals. Br Dent J 186, 278–281 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800087

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800087

This article is cited by

-

Difficulties experienced by dentists and orthodontists regarding ethical issues when announcing the diagnosis of a rare oral disease: a qualitative study in Marseille, France

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2024)

-

Feelings, perceptions, and expectations of patients during the process of oral cancer diagnosis

Supportive Care in Cancer (2016)

-

The emotional effects of tooth loss: a preliminary quantitative study

British Dental Journal (2000)