Key Points

-

Identifies the large variety of oral health materials for young children and their parents.

-

Provides a methodology with which to evaluate the quality of oral health promotion materials.

-

Reinforces key messages to members of the dental team.

-

Adds further evidence to support the development of oral health promotion materials which are clear, consistent, evidence-based and underpinned by psychological theory.

Abstract

Objectives To examine the quality of UK-based oral health promotion materials (OHPM) for parents of young children aged 0-5 years old.

Data sources OHPM were obtained via email request to dental public health consultants and oral health promotion teams in the UK, structured web-based searches or collected from oral health events.

Data selection Materials were included if: they were freely available; they were in English; they were parent facing and included oral health advice aimed at children aged 0-5-years-old.

Data extraction Quality assessment was based on: whether the oral health messages were consistent with Public Health England's Delivering better oral health guidance, and what barriers to good oral health were addressed by the OHPM using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

Data synthesis A wide range of printed and digital OHPM were identified (n = 111). However, only one piece of material covered all 16 guidance points identified in Public Health England's Delivering better oral health (mean 6, SD 4), and one other material addressed all 12 domains of the TDF (mean 6, SD 2).

Conclusions Although there were examples of high quality, further development is required to ensure OHPM are clear, consistent and address a wider range of barriers to good oral health behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental caries is the most common chronic disease affecting children. In the most recent Child Dental Health Survey, decay was present in 31% of five-year-olds and 46% of eight-year-olds.1 Moreover, there are significant health inequalities in oral health, with children from more deprived backgrounds having a greater likelihood of experiencing poor oral health than their same age counterparts.1 Caries causes pain and suffering as well as changing what children eat, their speech, quality of life, self-esteem and social confidence.2,3,4,5,6,7 In addition, the need for dental treatment has a significant impact on school readiness, therefore limits their ability to benefit from education and develop emotionally, behaviourally and socially.8 Furthermore, it is the most common reason for young children to have to attend hospital for a general anaesthetic, which places a substantial burden not only on the child, but their family9 and the NHS.10

Both the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)11 and Public Health England (PHE)8 have emphasised the importance of early intervention in the prevention of dental caries in childhood. As such, numerous organisations have sought to promote good oral health in young children with the aim of reducing the prevalence of dental caries. There is a lack of a standardised format to these resources and it is uncertain whether all materials adhere to current guidance or whether they address barriers to good oral health practices. Currently in England, PHE has developed an evidence-based oral health toolkit called Delivering better oral health12 which includes detailed guidance for children aged 0-6 years (Box 1). Furthermore, the delivery of oral health promotion is evolving with the use of modern technology translating print-based materials onto digital platforms. The benefits include digital media costing less to replicate than print-based materials, being easier to update and permitting multiple styles of presentation such as website and phone app. These are significant advantages, especially in the current climate of financial restraint. A key priority therefore is to assess the quality of these materials, especially in terms of whether they are they all providing the correct oral health advice and are they effectively addressing all the barriers to good oral health in young children. The reason for this is twofold. First, to assess if such materials already exist, and therefore can be used nationally in their current form or with modification. Second, to identify where problems with current materials lie and what can be improved. As such, this paper provides advice for developers to ensure future materials are designed to effectively target key barriers to good oral health practices, which is underpinned by appropriate psychological theory.

Psychological theory is increasingly being utilised within dentistry, and indeed, such an approach has numerous benefits. For instance, two recent systematic reviews on the use of psychological theory in oral health promotion have shown psychological interventions are more effective in improving oral hygiene, gingival health, plaque-index and self-efficacy in tooth brushing compared to traditional education/information based interventions.13,14 The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) is a particularly useful psychological framework that has been used to successfully identify important determinants of dental behaviours.15,16 The TDF17 is a comprehensive list of the determinants of behaviour derived from 33 behaviour change theories. It identifies 12 key domains thought to influence behaviour, including knowledge, skills, motivation and goals, beliefs about capabilities, social influences and behaviour regulation (see Table 1 for full list). Furthermore, it provides a valuable framework for assessing the psychological determinants of behaviour at all levels of influence (individual, interpersonal and environmental); thus provides an underlying scientific rigor and allows the mechanism of action within interventions to be studied.

Traditionally, oral health promotion has focused on knowledge transfer, however, there is little evidence to show improvements in knowledge lead to long-term behaviour change.14 Furthermore, earlier work undertaken by our inter-disciplinary research group via a systematic review,18 qualitative interviews with parents of young children19 and patient and public engagement20 identified that barriers and facilitators to good oral health practices are spread across all the domains outlined in the Theoretical Domains Framework. Thus oral health promotion materials need to address a range of barriers to support the adoption of good oral health practices. Key barriers where practical advice is needed for pre-school aged children are beliefs in capabilities (confidence in how to correctly perform oral health practices), behaviour regulation (managing the behaviour of an uncooperative toddler), nature of the behaviour (setting oral health routines), and social influences (the influence of family, friends and health professionals on oral health behaviours).

The current review aims to examine the quality of UK-based oral health promotion materials for parents of young children (0-5 [inclusive] years old). It identifies examples of good practice and draws attention to gaps in the current provision of oral health materials by assessing:

-

1

Whether the oral health messages are consistent with Public Health England's (PHE) Delivering better oral health guidance12

-

2

What barriers to good oral health are addressed by the materials using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

Method

Search and inclusion/exclusion criteria

The search for materials was conducted between January and February 2016, with oral health promotion materials being obtained from three key sources based on the recommendations of a University of Leeds information specialist with expertise in review methodology and guidance from Public Health England:

-

1

Advertisement requesting examples of materials adhering to the inclusion criteria. These requests were sent to all consultants in dental public health and to all members of the National Oral Health Promotion Group. These individuals were asked to circulate our request to the wider members of the oral health promotion community

-

2

Internet searches were conducted using the Google search engine. To ensure only UK based materials were included site limits were imposed to university (.ac), NHS (.nhs), government (.gov), organisation (.org), and company (.co) as these can be followed by '.uk'. Using the advanced search option on Google our search terms were: leaflet OR book OR poster OR video OR cartoon OR app 'child oral health' site:nhs.uk, with the same search terms being run with each website type

-

3

Our ongoing research interest in children's oral health19,20 has led to the donation and collection of materials from various organisations, therefore any oral health promotion materials adhering to the inclusion criteria were included in the review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Oral health promotion materials were included if:

-

UK-based

-

Freely available

-

In English

-

Provided oral health guidance aimed towards children aged 0–5 (inclusive) years old

-

Included oral health practices covered in Delivering better oral health (see Box 1 for full list of recommendations)

-

Targeted parents or were parent-related (defined as materials for professionals (for example, health visitors, teachers etc), which would be given to parents either verbally or through physical resources (for example, leaflets), or materials aimed at children, but had dedicated parent features (for example, apps)

-

Oral health materials available as one of these electronic or physical forms: leaflet, book, poster, video, cartoon or app.

Oral health promotion materials were excluded if they:

-

Aimed beyond the 0–5-year-old (inclusive) age range. Although, where clear distinctions between the guidance for those within the age range and outside of the age range were present, the information specific to the 0–5-year-old (inclusive) age range was included in the review.

-

The oral health information is only provided as text-based webpages.

Coding

Each oral health promotion material identified for inclusion in the review was coded initially by a researcher with expertise in psychology and behaviour change (KG-B). A random ten percent of the materials were independently coded by a second reviewer (JO) with expertise in oral health. KG-B and JO subsequently met, reviewed their coding and following discussion agreed a standard framework. A customised data extraction proforma was used to extract information from each material regarding: type (for example, leaflet, video, song), length (that is, number of pages, duration of song/video in minutes), title, target audience, who provided the material and who it was developed by, topics covered, which Delivering better oral health guidelines were covered and their accuracy, and the barriers to oral health as defined by the Theoretical Domains Framework addressed.

Results

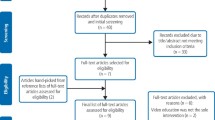

The search methodology identified 111 oral health promotion materials for inclusion in the current review (Fig. 1). [The oral health promotion materials included in this review were provided to the research team for this project with the understanding that we would not distribute them further. However, it may be possible to provide the contact details for those who kindly sent us a copy of their materials.]

Materials

The types of materials used to deliver oral health messages were wide ranging, including both print and digital media (Table 2). Nevertheless, of the 21 different types of oral health promotion materials identified, the majority (16/21) were print-based, with leaflets being the most popular oral health promotion material. The length of printed materials dedicated to oral health (considering some oral health promotion materials were embedded within wider health promotion materials) ranged between 1–109 pages. Digital materials (for example, songs, videos, radio infomercials) ranged in duration between 51 seconds – 16 minutes 45 seconds. Apps hosted a range of materials, including games and colouring books for children and parent dedicated leaflets/screens. Materials were primarily developed by three sources: the NHS/health institutions, local authorities, and dental/pharmaceutical companies. Thus, all the materials came from credible sources, primarily delivered through experts in oral health, with some instances including interactions with parents and children. With regards to the target audience, 85 materials were targeted at parents/carers, 13 targeted parents and children, seven targeted parents via health professionals and the wider childhood workforce, such as health visitors, teachers etc, and one material did not make clear who it targeted, thus could be used by both parents and children.

Delivering better oral health

There are 15 key points of oral health advice for children aged 0-5 (inclusive) years old covered in the Delivering better oral health guidance and we added visiting the dentist to the criteria, resulting in 16 key points. No single material covered all the evidence-based guidance outlined in Delivering better oral health (Table 2). The most commonly provided advice was regarding toothbrushing frequency, type of toothpaste, sugar consumption and visiting the dentist, whereas the type of toothbrush to use, brushing children's teeth upon eruption and fluoride varnish were less commonly covered. Many of the materials also included guidance beyond that contained within Delivering better oral health, with guidance frequently being on subjects such as dummies, replacing toothbrushes, flossing and reducing the spread of germs by not sharing toothbrushes and eating utensils.

Generally, the materials provided oral health advice in line with guidance. However, there were instances where information was inconsistent or incorrect, namely with regards to toothpaste amount, spitting rather than rinsing and dental visits. For example, three materials recommended a smear of toothpaste for under two-year-olds and a pea-sized amount for over two-year-olds, and one material recommended a pea-sized amount from six months – six years old. In addition, there was a lack of clarity in the guidance surrounding parental supervised toothbrushing (PSB). In the materials that did not explicitly address PSB, the wording was unclear and could possibly be implied, or it was advised that the child should brush independently. Even between materials that recommended PSB there were inconsistencies in the description of what it actually entails, with this including 'brushing', 'supervising', 'helping' and 'asking a grown up for assistance'. Moreover, these differing descriptions could be seen within the same material or despite recommending a parent's involvement in toothbrushing would also include pictures/video of children brushing their own teeth unaided.

Barriers to good oral health practices based on the Theoretical Domains Framework

Although all 12 barriers were addressed within the 111 materials, only one of the materials addressed all the barriers by themselves (Table 2). The range of barriers addressed within a single material was between 2 to 12. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that although technically the barriers were addressed it was not always to a high quality or correctly. For example, skills could be minimally addressed by simply providing what to use (that is, what toothbrush and toothpaste) and what to do (that is, instruction on the Delivering better oral health guidance), but lacked practical skills on how to actually brush a child's teeth (for example, position, brushing technique), set toothbrushing routines and manage children's behaviour. On the other hand with regards to social role the information was incorrect with in some cases responsibility being placed wholly on the child, which is contradictory to the guidance. The main barriers addressed included beliefs about consequences, skills, and the most commonly addressed barrier was knowledge. Barriers that were less well addressed included motivation and goals, memory, attention and decision process, and social/professional role and identity.

Discussion

This is the first review to examine the quality of UK-based oral health promotion materials for parents of young children (0-5 [inclusive] years old). This is a key piece of research as it not only reviews the quality of current provision, but also describes a robust methodology to support development and evaluation of future oral health promotion materials. The findings have revealed that although there are examples of good practice within existing health promotion materials there are issues with consistency and clarity that need to be addressed to ensure future materials deliver clear evidence-based messages to parents. Each of which will be discussed in turn.

Methodology

The current paper is the first of its kind to apply a robust review methodology to materials of this nature, and it is hoped that this approach will be useful to researchers who wish to conduct such research in the future. However, it has not been without its challenges. Unlike a traditional systematic review where various electronic databases are employed to search for literature, no such database system collates health promotion materials. Therefore, a pragmatic and informed approach had to be adopted to gather materials. Furthermore, as the review includes digital materials it has to be recognised that there are ongoing updates of such materials, and thus these changes could alter results. A realistic approach was taken to web-based materials with videos, games and leaflets that are accessible on the web included. Simple text-based webpages were excluded, as the vast volume of such pages that exist would make the review unmanageable to undertake. A key strength of the current review was the use of two independent experts to code the materials for quality (that is, DBOH guidance and TDF barriers addressed), therefore ensuring the coding was reliable and valid. In addition, this allowed us to identify where and how barriers to oral health care had been addressed at a superficial level and a deeper level, which can be seen in Table 3. This guidance on the assessment of different TDF domains will permit other research groups to use this methodology in the future for the evaluation and development of health promotion materials.

Materials

The findings revealed that the majority of oral health promotion materials were print-based, with leaflets commonly being used. The problem, however, with the reliance on print-based materials is that although there are indeed an effective means of transferring knowledge to the public, there is no evidence to support their effectiveness in changing behaviour.13 Moreover, print-based materials may restrict the number of barriers to oral health behaviour that can be sufficiently addressed, due to constraints on space and budget. On the other hand, although longer materials may address more barriers, they also may lose their appeal and appear burdensome to the target audience. Digitalisation of oral health promotion materials may help to remove these constraints and therefore allow a greater number of barriers to be addressed. In addition, making digital materials available via the internet provides the opportunity to share materials to a wider audience as they are easily accessible and freely available. A small number of materials were used by multiple organisations in different formats utilising both print and digital formats of the same material. However, irrespective of how many formats or organisations used the same material, the material was only counted once in the results as it was the same information that was presented. Indeed, it must be acknowledged that due to the unique nature of the review investigating both printed and digital media we have had to adopt a customised search strategy, especially as no databases exist that collate such materials. Nevertheless, despite consulting with an expert with regards to the search strategy, it does have its limitations in terms of being dependent on responses from outside organisations and the searching algorithms used by internet search engines. Another limitation is that it is possible that ongoing development of some digital media (for example, apps) may mean the materials have changed since data extraction.

Another important issue regards the source of the materials. In the present review materials were primarily developed by three sources: the NHS/health institutions, local authorities, and dental/pharmaceutical companies. Thus, all the materials came from credible sources, primarily delivered through experts in oral health, with some instances including interactions with parents and children. The nature of the source providing oral health advice is important, as it can be a barrier or facilitator to the effectiveness of oral health promotion.14 The target audience must trust those who are giving the advice, and feel as though they empathise with them, thus depending on the audience credible sources could include dental professionals, community workers and peers, with this being of key importance considering verbally presented oral health advice can be particularly effective in improving oral health.14

Delivering better oral health

Firstly, it has to be acknowledged that the Delivering better oral health toolkit provides guidance for children aged 0-6; however, we chose to focus on the age range of 0-5 (inclusive) years old. The reasons for which are threefold. First, a number of materials grouped their own materials from 0-5 years old and from six years onwards, thus going beyond the age based guidance provided by the Delivering better oral health toolkit. Second, for most children the permanent dentition erupts around the age of six with differing preventive advice provided; the focus for our review was the primary dentition. Third, in the UK it is mandatory for all children to begin school at the age of five, and this research aimed to focus on the oral health of preschool children.

Overall, all the materials included in the review presented advice in line with the Delivering better oral health guidance, but there were key areas where a lack of consistency and clarity were evident. Inconsistencies were particularly found with regards to the appropriate amount of toothpaste to use at different ages, spitting out toothpaste rather than rinsing and dental appointments (initiation and regularity). However, it is possible that some of these materials may have been produced before 2009 when the Delivering better oral health guidance first emerged. Nevertheless, there is a need to remove/update such materials as it is vital to present a clear oral health message that is consistent nationally to ensure parents are receiving the correct information and avoid confusion, especially as evidence shows adherence to such behaviours has a beneficial impact on caries development. For example, a recent systematic review showed that toothbrushing twice a day with fluoride toothpaste reduces the incidence of carious lesions.21 Similarly, clarity was lacking with regards to the appropriate type of toothbrush to use and the nature of parental supervised toothbrushing, with vague terms being used to describe both of these guidelines. Once more, the problem with using unclear descriptions that are open to interpretation is that it perpetuates parental confusion over correct oral health care for their children. This is of particular concern as parental supervised toothbrushing is an important means of preventing caries,22,23 yet evidence shows current practice is low.1 The best examples addressing parental supervised toothbrushing made clear statements that the parents should brush the child's teeth both verbally and pictorially or explained how the level of involvement may change as the child increased in age with greater independence being given as children approached preschool age, but still aided by a parent nevertheless. Furthermore, good examples included information on positioning while brushing a child's teeth and how to brush a child's teeth that could be further demonstrated pictorially. In a similar vein, the best examples providing advice on diet included how to identify sugar on food labels, examples of high-sugar snacks and healthy snacks, or included The eatwell guide.24

Barriers to good oral health practices based on the Theoretical Domains Framework

It is unsurprising that knowledge was the key barrier addressed, as this is the basis of most health promotion materials. However, there is little evidence to show improved knowledge leads to improved oral health behaviour.14 Therefore, there is a need for future oral health promotion materials to attempt to address as many barriers to oral health as possible within the constraints of the medium of delivery. The increasing use of digital media may help to address a wider number of barriers to good oral health practices. For example, digital media (for example, videos, animations) may be particularly useful to actively demonstrate practical skills. Indeed, previous research18,19has shown that the main barriers experienced by parents relate not to knowledge, but to skills, beliefs about capabilities, social influences, behaviour regulation and routine setting (nature of the behaviour). Within the current review the best examples addressed these barriers through demonstration, providing practical advice/resources and empathising with the parent (Table 3).

Conclusions

Broadly, the majority of materials available to parents of 0-5-year-olds adhere to the guidance provided by Delivering better oral health and there is evidence of good practice in those materials addressing the barriers of social influences and behaviour regulation, which can be particularly problematic for parents. However, there is a need to ensure that the guidance provided is clear and correct, as there were a number of instances where clarity and consistency was lacking in currently available materials, predominantly regarding parental supervised toothbrushing. Moreover, with our underpinning work which shows barriers to good oral health are spread across all of the TDF domains we have developed a robust methodology with which to quality assure oral health promotion material. This will help not only with the development of future oral health promotion materials by highlighting what barriers to address and providing examples of good practice on how to address them, but also evaluation of oral health promotion materials in the future, both in this area and other pertinent areas of oral health

Listen to the author talk about the key findings in this paper in the associated video abstract. Available in the supplementary information online and on the BDJ Youtube channel via http://go.nature.com/bdjyoutube

References

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Children's Dental Health Survey 2013. Report 2: Dental Disease and Damage in Children. England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2015. Available at: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB17137 (accessed 31 January 2017).

Sheiham A . Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83: 644.

Shepherd M A, Nadanovsky P, Sheiham A . The prevalence and impact of dental pain in 8-year-old school children in Harrow, England. Br Dent J 1999; 187: 38–41.

Krisdapong S, Sheiham A, Tsakos G . Oral health-related quality of life of 12- and 15-year-old Thai children: findings from a national survey. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2009; 37: 509–517.

Gilchrist F, Marshman Z, Deery C, Rodd H D . The impact of dental caries on children and young people: what they have to say? Int J Paediatr Dent 2015; 25: 327–338.

Murray C J, Richards M A, Newton J N et al. UK health performance: findings of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013; 381: 997–1020.

American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr Dent 2008; 30: 40–43.

Public Health England. Local authorities improving oral health: commissioning better oral health for children and young people: An evidence-informed toolkit for local authorities. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-oral-health-an-evidence-informed-toolkit-for-local-authorities (accessed 31 January 2017).

Goodwin M, Sanders C, Davies G, Walsh, T, Pretty I. Issues arising following a referral and subsequent wait for extraction under general anaesthetic: impact on children. BMC Oral Health 2015; 15: 3.

Department of Health. National schedule of reference costs 2011–12. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213060/2011-12-reference-costs-publication.pdf (accessed 31 January 2017).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Oral health: approaches for local authorities and their partners to improve the oral health of their communities. NICE Public health guidance 55. October 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph55 (accessed 31 January 2017).

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2014. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/367563/DBOHv32014OCTMainDocument_3.pdf (accessed 31 January 2017).

Werner H, Hakeberg M, Dahlstrom L et al. Psychological Interventions for poor oral health: a systematic review. J Dent Res 2016; 95: 506–514.

Kay E, Vascott D, Hocking A, Nield H, Dorr C, Barrett H . A review of approaches for dental practice teams for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2016; 44: 313–330.

Gnich W, Bonetti D, Sherriff A, Sharma S, Conway D I, Macpherson L M . Use of the theoretical domains framework to further understanding of what influences application of fluoride varnish to children's teeth: a national survey of general dental practitioners in Scotland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2015; 43: 272–281.

Bonetti D, Clarkson J E . The challenges of designing and evaluating complex interventions. Community Dent Health 2010; 27: 130–132.

Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S . Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 37.

Aliakbari E, Gray-Burrows K, Vinall-Collier K, Marshman Z, McEachan R, Day P . Systematic review of home-based toothbrushing practices by parents of young children to reduce dental caries. BMC Oral Health. In submission.

Marshman Z, Ahern S M, McEachan R R C, Rogers H J, Gray-Burrows K A, Day P F . Parents' experiences of toothbrushing with children: a qualitative study. JDR Clinical & Translational Research 2016; 1: 122–130.

Gray-Burrows K A, Day P F, Marshman Z, Aliakbari E, Prady S L, McEachan R R C . Using intervention mapping to develop a home-based parental-supervised toothbrushing intervention for young children. Implement Sci 2016; 11: 1–14.

Scheerman J F M, van Loveren C, van Meijel B et al. Psychosocial correlates of oral hygiene behaviour in people aged 9 to 19 – a systematic review with meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2016; 44: 331–341.

Pine C M, Adair P M, Nicoll A D et al. International comparisons of health inequalities in childhood dental caries. Community Dent Health 2004; 21: 121–130.

Broadbent J M, Thomson M, Boyens J V, Poulton R . Dental plaque and oral health during the first 32 years of life. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142: 415–426.

Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide: Helping you eat a healthy, balanced diet. 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide (accessed 31 January 2017).

Acknowledgements

This publication is independent research commissioned and funded by Leeds City Council. This study is part of the healthy children healthy families theme of the NIHR CLAHRC Yorkshire and Humber, IS-CLA-0113-10020. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Supplementary information

Appendix 1

Search terms (MP4 200531 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gray-Burrows, K., Owen, J. & Day, P. Learning from good practice: a review of current oral health promotion materials for parents of young children. Br Dent J 222, 937–943 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.543

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.543

This article is cited by

-

Effectiveness of an integrated model of oral health-promoting schools in improving children's knowledge and the KAP of their parents, Iran

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

“Strong Teeth”: the acceptability of an early-phase feasibility trial of an oral health intervention delivered by dental teams to parents of young children

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

“Strong Teeth”—a study protocol for an early-phase feasibility trial of a complex oral health intervention delivered by dental teams to parents of young children

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2019)

-

The DIKW pathway: a route to effective oral health promotion?

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

HABIT—an early phase study to explore an oral health intervention delivered by health visitors to parents with young children aged 9–12 months: study protocol

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2018)