Key Points

-

Summarises key points of the Mental Capacity Act.

-

Describes the practical aspects of using the principles of the Mental Capacity Act in every day practice.

-

Describes the interlinking factors that should be considered when consenting patients who lack mental capacity for dental treatment.

-

Provides 'real life' examples of the management of a spectrum of patients who lack mental capacity.

Abstract

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a legal framework within which specific decisions must be made when an individual lacks the mental capacity to make such decisions for themselves. With an increasingly aged, medically complex and in some cases socially isolated population presenting for dental care, dentists need to have a sound understanding of the appropriate management of patients who lack capacity to consent to treatment when they present in the dental setting. Patients with acute symptoms requiring urgent care and un-befriended patients present additional complexities. In these situations a lack of familiarity with how best to proceed and confusion in the interpretation of relevant guidance, combined with the working time pressures experienced in dental practice may further delay the timely dental management of vulnerable patients. We will present and discuss the treatment of three patients who were found to lack the mental capacity necessary to make decisions about their dental care and illustrate how their differing situations determined the appropriate management for each.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA)1 provides a legal framework within which specific decisions regarding an individual's health and welfare, and property and financial matters, must be made when that individual lacks the capacity to make such decisions for themselves. This includes decisions about medical and dental care. It can also be used prospectively by those who wish to make preparations for a time in the future when they might lack mental capacity.

The MCA is based upon the following five statutory principles:

-

Individuals must be assumed to have mental capacity until it is established that this is not the case

-

All practicable steps must have been taken to help and support someone to make a decision for themselves

-

An unwise decision does not in itself indicate a lack of capacity

-

Any decision made or act undertaken on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be in the individual's best interests

-

Any act undertaken or decision made should be the least restrictive option to the person concerned in terms of their rights and their freedom of action.

Some individuals have a legal duty to act in accordance with the MCA when caring for adults who lack mental capacity. These include:

-

Those acting in a professional capacity for, or in relation to, a person who lacks capacity

-

Those who are being paid to act for or in relation to a person who lacks capacity.

Those who are deemed to be acting in a professional capacity include:

-

Healthcare staff including doctors, dentists and nurses

-

Social care staff including social workers and care home managers

-

Others who may be involved in the care of people who lack capacity when they are unable to make a required decision including ambulance crew, paramedics or police officers.

While one adult cannot give consent for another adult to undergo medical or dental treatment, the MCA provides a legal framework to safeguard decision-making on behalf of patients who have been found in a two stage test to lack capacity to make these decisions for themselves, thus ensuring that the treatment provided is in their best interests.

While a clinician's decision about a patient's ability to demonstrate mental capacity may be subjective, there are well-defined criteria that can be used to assist and structure their decision making. The MCA sets out a two-stage test of mental capacity.

Stage One of the mental capacity assessment requires proof that the patient has an impairment of the mind or a disturbance that affects the functioning of their brain. Examples of impairment in the functioning of the mind or brain include:

-

Conditions associated with some forms of mental illness

-

Dementia

-

Significant learning disabilities

-

Long-term effects of brain damage

-

Physical or medical conditions that cause confusion, drowsiness or loss of consciousness

-

Delirium

-

Concussion following a head injury

-

Symptoms of alcohol or drug use.

Stage Two seeks to establish whether the impairment or disturbance affects a patient's ability to make a specific decision. In accordance with Principle 2 of the MCA, however, every possible attempt must be made to assist a patient in the decision-making process.

Often individuals who lack capacity will be cared for and/or accompanied to dental appointments by their next of kin, family members, partners or carers who are familiar with the patient's history and need for treatment. These individuals can be asked for their opinion of appropriate treatment options. Collectively these opinions, together with those of health and social care professionals, will contribute to a best interests process in which a decision regarding the most appropriate treatment for the patient can be reached.

A lasting power of attorney (LPA) is registered with the Office of the Public Guardian and ensures that an individual has a choice of whom the power of decision-making can be delegated to should he or she suffer an impairment or a loss of mental capacity. An LPA can be appointed for health and welfare, or property and financial affairs. In this article we will only consider the role of a health and welfare LPA who is appointed and granted the power to make medical decisions for an individual who demonstrates a loss of capacity.

In circumstances where a patient is un-befriended (without any next of kin, parents or children) and the treatment that they require is considered to be urgent a Consent Form 4 can be used to establish and document that the urgent treatment being proposed is in the patient's best interests. This requires a formally documented discussion between two clinicians and justification of the treatment proposed. The Department of Health no longer produces a generic Consent Form 4 and the responsibility of formulating and updating a local version of this form now lies with hospital trusts. We include a copy of our own as an example (Fig. 1).

When, however, an un-befriended patient requires serious but non-urgent medical treatment or a change of accommodation, neither the completion of a Consent Form 4 nor a best interests meeting (BIM) is appropriate. Instead, an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) should be appointed to establish that the proposed treatment is indeed in the patient's best interest. Routine extraction of a tooth under local anaesthetic is not deemed as serious medical treatment. Consequently, this step is unlikely to be necessary in primary dental care. However, if a patient is to receive dental treatment under general anaesthetic in secondary care this may be necessary.

We will present and discuss the management of three patients who were found to lack the mental capacity necessary to make decisions about their dental care. The management of each patient differed because of the urgency with which their dental treatment was required and their social circumstances. With an increasingly aged, medically complex and in some cases socially isolated population presenting for dental care dentists need to have a sound understanding of the appropriate management of patients who lack mental capacity when they present in the dental setting. We will highlight the important factors to consider when assessing the needs of this patient group.

Case 1

Involving a best interests meeting to establish that the proposed dental treatment plan was appropriate

A 48-year-old male was referred to the Department of Special Care Dentistry at King's College Hospital for a dental assessment and appropriate treatment. The patient had been diagnosed as having profound learning disabilities and was unable to communicate verbally. He also had visual and hearing impairments and challenging behaviour.

The patient attended with his mother who explained that her son had recently begun to clench his jaw and hold the left side of his face. He had been waking up at night and rubbing his head on his pillow. The patient's mother had not observed the patient exhibiting such behaviour in the past and believed that these changes in her son's behaviour were a sign that he was experiencing toothache.

A dental examination was attempted but was unsuccessful because of the patient's limited cooperation. Given the lack of compliance and the visible distress caused to the patient by the clinical examination, radiographs were not attempted. Support was provided to the patient to enable him to make decisions about his treatment for himself. This included ensuring that the patient attended with his mother, scheduling the appointment at the best time of day for the patient and allowing sufficient time during the appointment to examine the patient. A capacity assessment was performed by the treating consulting who also acted as the decision maker and the patient was subsequently deemed to lack the mental capacity required to provide informed consent for dental examination or treatment.

A BIM was subsequently conducted with the following individuals present:

-

The patient

-

The patient's mother

-

The community learning disability nurse involved in the patient's care

-

The patient's carer

-

A consultant in special care dentistry.

During the BIM, treatment under local anaesthetic, intravenous sedation with local anaesthetic and general anaesthetic were all considered. It was noted that because of the patient's limited cooperation and the difficulty of performing a dental examination, his most recent episode of dental treatment had been five years previously. In order to establish a definitive treatment plan and confirm the cause of his dental pain it was considered necessary for the patient to have dental radiographs taken. However, it was the attending consultant's opinion, from experience, that taking a comprehensive set of radiographs for a patient under conscious sedation would be challenging. Furthermore, the patient required routine restorative and periodontal treatment as well as dental extractions and it was unlikely that all of this would be able to be performed in one appointment under conscious sedation with intravenous midazolam. In light all of these factors it was decided that dental treatment under general anaesthesia would be in the patient's best interests. This would include a dental examination, radiographs and treatment including scaling, restorative treatment and extractions.

After the BIM all those in attendance were asked to respond in writing with their opinions regarding the proposed treatment plan. The treatment plan was not contested; all parties agreed that it was in the patient's best interests. A Consent Form 4 was used to document consent for this treatment which was carried out as planned without complication under a day case general anaesthetic.

Case 2

Involving the instruction of an IMCA to establish that the proposed dental treatment plan was in a patient's best interest

A 29-year-old Albanian woman was referred by her general dental practitioner (GDP) to the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Hospital for a full dental clearance. Her GDP had committed to the subsequent provision of upper and lower complete dentures following a suitable period of healing. The patient attended with a carer who explained that the patient had a moderate learning disability and lived in supported accommodation.

The patient attended an assessment appointment with her carer and was able to converse with the dentist who saw her without any language barrier. She clearly indicated that her main concern was an inability to chew food and she described episodes of intermittent pain associated with some of her teeth. She was, however, unable to provide a clear history of her symptoms.

Intra-oral examination revealed a neglected, grossly carious, partial adult dentition. The patient was found to have multiple retained roots and a periodontally compromised lower labial segment.

Several attempts were made to satisfactorily explain to the patient that she required the removal of all her remaining teeth. These were unsuccessful and it became apparent that the patient lacked the ability to recall and demonstrate an understanding of the information necessary for her to consent to the proposed treatment plan because of her moderate learning disability.

A panoramic radiograph (Fig. 2) supported the attending dentist's clinical impression that a dental clearance was indicated. Given the dentist's belief that the patient lacked the capacity to consent to the proposed dental treatment, it was not considered appropriate to ask her to do this and no treatment was arranged for the patient at this point. Arrangements were made for the patient to return to clinic with a carer for a follow up appointment.

At the next appointment a capacity assessment was performed which determined that the patient lacked the mental capacity required to consent for her dental treatment. Since the patient did not have any family, friends or next of kin who could be contacted to be involved in planning her care, it was not considered appropriate for a BIM to be scheduled. Instead, because this lady's treatment was not urgent and she was un-befriended, an IMCA was instructed.

The IMCA visited the patient in her own home and undertook an independent assessment of her mental capacity. This confirmed that the patient lacked capacity. The IMCA's assessment of the patient's understanding of the proposed treatment and her feelings about this provided a foundation upon which a decision was made to proceed with the proposed dental clearance in the patient's best interests.

The patient was successfully treated without complication under a day case general anaesthetic and was discharged to home in the care of an appropriate and reliable adult escort.

Case 3

Management of a patient who lacked capacity but who required urgent dental treatment

An 82-year-old man was referred by his GDP to the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Hospital for the extraction of several teeth in the upper labial segment. The patient had a known diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. He attended with his daughter who explained that her father had recently begun to hold the front of his mouth which she had interpreted as a sign of him being in pain.

A clinical examination revealed multiple, grossly carious retained roots. Radiographs received from the referring GDP revealed periapical pathology associated with the retained roots.

Given that the patient was apparently in pain at the time of presentation, the decision was made that it would be appropriate for a BIM to be conducted immediately in clinic. A Consent Form 4 was used to document the agreement of two clinicians and the patient's daughter that the extraction of the painful retained roots would be in the patient's best interests. The extractions were then completed under local anaesthetic without complication.

Discussion

A patient who requires dental or medical treatment must freely give their informed consent to avoid the intervention that they receive being considered an assault. It is therefore necessary to consider the ability, or mental capacity, of a patient to provide their consent for treatment as part of the consent process. The vast majority of patients presenting to dentists for treatment will clearly demonstrate mental capacity to consent for treatment. On rare occasions, however, a patient who requires a formal mental capacity assessment will be encountered.

The MCA determines that for a patient to be considered to have capacity to consent to medical or dental treatment they must demonstrate that they are able to:

-

Understand the information provided about their treatment

-

Understand why the treatment is needed and the advantages, disadvantages and risks and/or benefits of receiving or not receiving the proposed treatment

-

Retain the information provided

-

Use or weigh-up the information relating to their treatment

-

Communicate their decision about proposed treatment using either verbal or non-verbal methods of communication.

Conversely, a person who is considered to lack capacity is defined as an individual who, at the time of capacity assessment, is 'unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain'.1

This definition recognises that there are instances where a person may lack capacity to make some decisions but can demonstrate continuing capacity to make others. The definition also acknowledges that some individuals who lack capacity may recover from the condition causing them to lack capacity or develop skills which will allow them to regain capacity in the future.

The mental impairment or disturbance compromising capacity can be transient or capacity may fluctuate so that an individual can lack capacity at the time of assessment and clinical decision-making, but regain this at another point in time if the loss of capacity is partial or variable. Capacity may be better in certain environments such as the patient's place of residence or at certain times of the day. It is therefore important that healthcare providers recognise the need to reassess decisions made about a patient's mental capacity and that they appreciate that these are time and decision specific.

It is important to note that challenging behaviour or a lack of compliance with dental treatment does not equate to a lack of mental capacity. Equally, compliant behaviour is not an indication that the patient has the mental capacity to consent for treatment.

Patients may present to dentists with varying levels of capacity. While some may be able to consent for simple procedures such as an intra-oral examination, they may not be able to fully understand, retain or appreciate the need for and the nature of more complex, invasive or risky procedures.

Whenever it is considered that a patient may lack capacity to consent to treatment a clinician must demonstrate and document that on the balance of probabilities it is more likely than not that a patient lacks mental capacity to make a specific decision at the specific time the decision needs to be made.

The consent process for patients lacking mental capacity

All decisions about medical or dental care must be made in the patient's best interests. However, the term 'best interests' is not defined by the MCA. Instead, the principles of the MCA act as a guide, the application of which allows the best interests of a patient to be determined.

It is the responsibility of the clinical 'decision maker' having considered all possible treatment options (including no treatment) to ascertain which represents that which is the best for the patient. The patient's past and present wishes and feelings and other factors known to be of importance to them should also be taken into account. In the provision of dental care, the attending dentist often carries out the BIM. However, the dentist who conducts the BIM may not necessarily perform treatment. The decision-maker is the clinician that will be responsible for carrying out treatment.

A number of health and social care professionals with a role in the care of the male patient discussed in case 1 were involved in the BIM regarding his dental treatment. While none of these individuals could provide or withhold consent on behalf of the patient there is a statutory duty for any individual with an interest in the patient's welfare to be consulted. The opinions of these individuals were considered as part of the decision-making process in this case.

In England and Wales an individual who has capacity may appoint an attorney under a LPA for health and welfare to authorise medical decisions on their behalf if they subsequently lose mental capacity. The attorney cannot, however, demand a specific form of medical or dental treatment for a patient. A court appointed deputy can also be appointed and authorised by the Court of Protection to make decisions regarding personal welfare, including decisions regarding medical care. An advance decision to refuse treatment can also be made by an individual at a time when they demonstrate capacity in order to refuse treatment during a time for when they may lose mental capacity.

Healthcare professionals have an obligation to respect and protect the confidentiality of patients, but if a patient lacks capacity to make a decision about disclosing confidential information, this decision can be made by an attorney acting under a health and welfare LPA, health professionals who are acting in the patient's best interests or by court appointed deputies. In such cases it is inevitable that information regarding the patient's treatment will be need to be shared to ensure that treatment is performed in the patient's best interests.

Any treatment which is carried out in the best interest of patients who lack capacity must be delivered in a way that places least restriction on the patient's rights and freedom of action.1 In dentistry this means that where possible dental treatment should be carried out under local anaesthetic rather than conscious sedation or general anaesthetic. As the most restrictive option, general anaesthetic should only be used to facilitate dental treatment when this cannot be delivered effectively and safely in any other way.

In case 3 a decision was made to treat the patient under local anaesthetic as this was the least restrictive option and the patient was fully cooperative with this.

In most cases the decision-maker conducts a BIM. In both primary and secondary care this decision-making process is often documented through the completion of a Consent Form 4. We have also devised a 'Best Interests' letter (Fig. 3) and BIM agenda template (Fig. 4) which can be used to direct and support the decision making process.

In an ideal world a BIM should be conducted in a formal setting with all parties present to discuss the proposed treatment. In many cases, however, this is not practical. In such cases, individuals with an interest in the well-being of the patient can be provided with a written treatment plan and justification of the treatment proposed. Following receipt of this, these individuals can reply in writing with their response to and opinions of the proposed treatment. In all cases a written record of correspondence and related discussions should be retained to form part of the patient's contemporaneous clinical records.

In some cases a consensus regarding proposed treatment may not be achieved. In order to resolve a dispute regarding the best interests of a patient, consideration should be given to obtaining specialist and legal advice and even making an application to the Court of Protection. In cases where a patient is at risk of harm as a consequence of delayed treatment, an urgent referral should be made to the Court of Protection. While rarely encountered in general dental practice, it may also be necessary to seek prior court approval where there are significant consequences for the patient or where a level of restraint will result in a deprivation of liberty.

Increasingly, it has become necessary to appoint an IMCA to determine and represent the patient's best interests. This is usually necessary when a patient who is un-befriended is found to lack capacity to consent for non-urgent treatment.

Independent mental capacity advocate

The role of the IMCA service is to provide an independent safeguard to represent the best interests of patients who lack capacity to make decisions for themselves.

An IMCA should be instructed when:1

-

An NHS body is proposing to provide, withhold or stop serious medical treatment

-

An NHS body or local authority is proposing to change a patient's accommodation in a hospital or care home

The appointment of an IMCA is a legal right for any patient over the age of 16 years when the following criteria apply:1

-

The patient lacks mental capacity

-

The patient does not have any family members or next of kin to represent their views

-

The medical treatment that they require is not urgent.

The need to appoint an IMCA is uncommon in primary or secondary dental care as it is unusual for the criteria above to be satisfied. It may, however, be appropriate when extensive dental treatment or treatment under general anaesthetic or conscious sedation is being considered for an un-befriended patient who lacks capacity. An IMCA may rarely be appointed in adult protection cases despite the presence of family members and friends.

The roles of an appointed IMCA include:

-

Ascertaining the patient's views and beliefs

-

Assessing other courses of medical action

-

Seeking a second medical opinion where appropriate

-

Challenging the decision made or proposed.

The IMCA service is provided without charge to either the referring clinician or patient. An IMCA provider is responsible for service delivery to patients in a designated county or borough. A referring dentist must therefore ensure that the patient is referred to the correct service. An IMCA will seek to ensure that the dental treatment provided is in the patient's best interests and they have the legal right to seek the opinion of independent healthcare professionals.

The planning of dental treatment and the delivery of this may be more time consuming and complicated for patients who lack capacity than the general population. Both are complicated by the requirement to ensure that relevant legal requirements and professional guidance are adhered to in order to ensure that the best interests of this vulnerable patient group are safeguarded.

Conclusion

In both primary and secondary dental care settings time constraints and lack of familiarity with relevant guidance can mean that dental care professionals who do not routinely treat patients who lack capacity feel ill equipped to manage them successfully. Consequently, the treatment of these patients may be delayed by a lack of clarity as to how best to proceed or by onward referral which may be clinically unnecessary and not in a patient's best interests. Thus, another barrier that hinders the ability of vulnerable patients with compromised oral health to access dental care may be introduced.

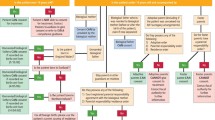

We have devised a simple guide which we believe will help dentists to identify the most appropriate course of action when considering the dental management of patients who may lack capacity (Fig. 5). The British Medical Associations Mental Capacity Act Toolkit2 is a freely accessible online resource which provides clear, user-friendly advice about the MCA, capacity assessment and best interests to complement the definitive guidance in this area.

References

Office of Public Sector Information. Mental Capacity Act. London: Department of Health, 2005.

British Medical Association. The Mental Capacity Act tool kit. BMA: London, 2016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Modgill, O., Bryant, C. & Moosajee, S. The Mental Capacity Act 2005: Considerations for obtaining consent for dental treatment. Br Dent J 222, 923–929 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.538

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.538